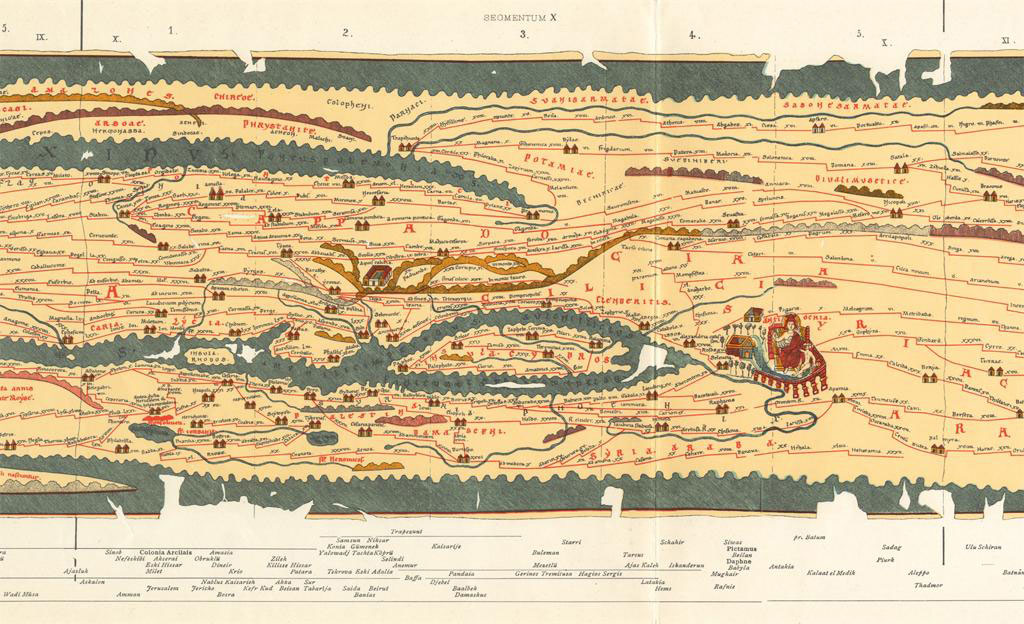

Upon entering Monditalia, Koolhaas’s reexamination of Italy’s place in the world in the context of this year’s Venice Architectural Biennale, one is overtaken by an extra-large-scaled shear curtain that acts as a device dividing the two sides of the exhibition—film and performance on the one side and architectural projects on the other. Stretching across the Corderie, the curtain structures the content of the projects and installations from colonial Libya to the Italian Alps (“South” to “North”) as it moves visitors from the central pavilion to the national pavilions (“West” to “East”). Upon closer scrutiny, one recognizes the Peutinger Map, a medieval copy of an ancient map used as an itinerary during Roman times. The map represents the Empire’s network of roads and cities, with marked distances and landscape features such as mountains, rivers, and sea as well as building icons that provide guidance to travelers and indicate possible stopping points. Closer to a contemporary city’s subway map than an accurate representation of scale and distances, the Peutinger Map’s original dimension and proportion (34 centimeters high by 6.7 meters long), stretched along the east-west axis, acts as a natural unifying spine and spectacular backdrop to the eclectic exhibition stations along it.

In an early presentation of the curatorial concept for the Biennale, Koolhaas declares the map “still entirely relevant.” As a representation of a network of cities in a state of constant exchange, the map offers the Roman Empire as a first representation of globalization, a thesis Koolhaas explores as part of the Roman Cities chapter of the Project on the City, which he leads in the late 1990s at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. With the scaling up of the map to both organize and occupy a long stretch of the Corderie, Koolhaas reasserts scale, and the Extra-Large in particular, as the most effective means for Architecture to produce complexity, effect, and even meaning in the age of endless expansion. In many ways, embodied within this moment of simultaneously appropriating the ancient map as a representation of globalization and blowing it up to a monumental scale is Koolhaas’s renewed embrace of “Bigness” as Architecture’s answer to the pressures of an increasingly globalized world.

Koolhaas’s enlisting of scale as a central preoccupation first crystalizes in 1995, when he publishes his seminal monograph S,M,L,XL and makes scale the central organizing principle for Architecture. In it, he outlines his manifesto for Bigness, in which he declares that scale and the complexity that it implies are the only way for Architecture to maintain relevance in the face of globalization. By studying shopping malls, hotels, airports, and the ubiquitous proliferation of endless privatized interiors, Koolhaas theorizes Architecture’s expansion and its displacement of “what used to be called the city.” As if in a desperate attempt to survive, Architecture’s scaling up parallels the flurry of radical urban discourses that emerge around that time—from the launch of New Urbanism, Koolhaas’s own Project on the City, and the reframing of Landscape Urbanism—all of which are developed at the expense of (and sometimes even against) Architecture, as an object whose scale and ideological/aesthetic preoccupations are perceived as incapable of addressing the complexity and magnitude of the social, infrastructural, and environmental challenges at hand, as the world continues its motion towards XL-scaled global urbanization.

And yet, the cost of Bigness is heavy. In its conflation of Architecture and the City, what is produced is, in fact, the impossibility for either one to exist. As Bigness leaves the Generic to merge with its alter ego, the Icon, Architecture finds itself increasingly under attack. From the mammoth city-scaled museums of Santiago Calatrava and Peter Eisenman in Spain (generally perceived as megalomaniac projects that contributed significantly to the country’s recent economic crisis) to the dozen stadia in Athens that were abandoned at the end of the Olympic Games (monuments to excess now in ruins, and symptoms of the country’s inability to mitigate the recent global recession), or the anger against similar-scaled structures completed in Brazil for the 2014 World Cup, it is not only Architecture’s metaphorical displacing of the City that is at stake, but the increasing perception that it is literally stifling efforts and resources that could otherwise be used toward housing, sewage, infrastructure, and other fundamental needs.

The irony of Bigness is that even as it equates Architecture with Urbanism, it doesn’t allow the former to appropriate the latter’s more productive aspects, such as the embrace of density, compression, intelligent and shared infrastructures, and a more careful integration of landscape and ecological systems. Instead, contemporary Architecture’s sheer scale and formal complexity tend to become simply wasteful and vain, even as it meets LEED’s golden points. To make matters worse, these environmental and social concerns have recently been magnified by serious ethical questions, with increasing reports on widespread labor abuses involved in the construction of global icons and glittering cities around the world. Faced with such distrust, and too often associated with excess and waste rather than with design intelligence and the possibility for more productive contributions, it has been difficult for Architecture to engage new, different, and more meaningful territories.

The cost of Bigness is heavy in other ways as well. Used as an overscaled index that fails to engage the exhibition’s content around it, the spectacular Peutinger curtain contributes instead to the overall sensory and informational overload one experiences throughout the Biennale, further depriving us of the possibility for more radical content, possible new readings, and a more precise and productive staging of new relations and perspectives across an exhibition whose exceptional and surprising moments are overwhelmed by sheer noise. Twenty years ago, Bigness produced a paradigm shift for Architecture, and the effects were both liberating and exhilarating. Today, it is as if the opposite is true—as the map is scaled up, its resolution is diminished and its complexity is sacrificed to reductive spectacle, one that does not allow for the possibility to extract meaningful clues from its representation and history in order to shift perspectives, reread the present, or rewrite the past toward the projection of a different future.

So what are the possible directions and embedded criticisms that the Peutinger Map opens up? First, it is the only strong moment in the exhibition that stands in sharp contrast to the stubborn celebration of the project of the nation-state, which the Venice Biennale continues to embrace and promote through its structure of “central and national pavilions.” Despite (or maybe because of) 2014’s unifying theme of “Absorbing Modernity” established by Koolhaas, questions of representation—the expression of cultural specificity and national identities through Architecture—were everywhere, and yet nowhere were the findings synthesized to counteract the claims made by the center (pavilion) of a continued center-periphery narrative, with the center’s drive for technological progress followed by the periphery’s slow and costly emergence “into modernity.”

In contrast, the Peutinger Map offers another possible reading. Moving away from the center-periphery narrative, it represents a world always already connected, where lines are not arrows, singularly pointing outward from Rome, but instead create a complex network of exchanges and flows. Inverting the Biennale’s figure-ground of intense pavilions—“Architecture,” with “nothing” in between—the Peutinger Map renders instead the field of generic icons/cities thick with meaning and information, as it represents infrastructure, the movement of travelers both human and animal, the exploitation of resources, the exchange of knowledge, and the deployment of power. It is a map that makes visible the complex and intertwined set of forces and relationships that shape the built environment.

In fact, and in contrast to the Nolli Map displayed on the floor a few stations into the Corderie, it is not only the “built” environment that the Peutinger Map renders visible, but the “unbuilt” as well. As the light yellow of the land is intertwined with the blue of the sea—in an almost nested fashion that suggests the possibility of many more turns and folds—it is a stretched landscape of built and unbuilt, solid and fluid, natural and man-made that is interlaced to produce an integrated understanding of the world, where no part exists in isolation, and no architectural wall is so strong as to keep the flows from eroding it. As the endless landscape of Venice’s hard surfaces continues to sink into the waters unstoppably rising around it, the Peutinger Map overwhelms with the urgency for us to reframe the relationship between the urban and the natural, with the possibility for Architecture (those little icons on the map) to negotiate the intersection of both.

Finally, it is in the representation of Rome, Constantinople, and Antioch that the complexity of meanings deployed by the Peutinger Map comes into sharpest focus, providing a strong foil for the Biennale exhibition as a whole. While the map’s excessive stretching in the east–west direction could lend itself to mirror the resilient contemporary narratives of difference, cultural specificity, and violent claims to identity exacerbated by the imposition of global forces onto local sites, the three figures provide instead a different narrative. They sit somewhat differentiated by the slightest variations in their accoutrement—with Antioch holding a scepter in one hand and a son in the other, Constantinople pointing to a statue with its crown on its lap, and Rome surrounded by a halo-like circle as it holds the globe in one hand and a shield in the other—but these three figures representing the key cities of the eastern and western Roman empires also sit equal, equally connected and very much the same.

More importantly, the drawing itself presents us with a surprising hybrid of medieval Catholic sensibility combined with that of ancient Byzantine icons, reinforcing the map’s overall manifesto for a multilayered, multi-connected, and already contaminated model of the world. It is as if within the drawing of these three figures, blown up beyond the possibility of recognition as they float in the space of the Corderie, there lies what could have been a more productive project for the Biennale: the final deconstruction of a singular, linear history of modernity (and architectural modernism)—a history that emanates outward from the center, where local and hybrid manifestations are necessarily less “pure,” “authentic,” and “original” than either the center’s established canon or the periphery’s traditional expressions of “identity.” In the constructed opposition between tradition and modernity, which this 14th Biennale builds on without undermining, the Peutinger Map reframes the dichotomy as if echoing Timothy Mitchell’s argument, developed in his seminal essay “The Stage of Modernity,” to consider the colonized as having always already been part of modernity.

Twenty years after “Bigness” posed the anxious question of how globalization would transform Architecture, it seems timely to declare the effects of capital and the pressures to develop all too well-known, as we stubbornly keep looking for, and carving out, new and different choices, however fragile and slim. As a first choice, finally divorcing Architecture from the Extra-Large would simultaneously re-inscribe environmental concerns as integral rather than solely tied to technological performance, as well as reframe the urban and the natural in a productive and intertwined relationship, as the icon is recast within the larger context of urban networks and natural systems. This scaling down would also invite a renewed understanding of iconicity and its responsibility, moving beyond the landscape of bloated icons whose representational qualities are all too unaware of their cultural significance to consider instead Architecture’s reengagement with the question of cultural diplomacy.

Despite the contestation of meaning produced by postmodern thinking in the West, today’s global expectation for Architecture to continue to represent is overwhelming. And yet, without a critical approach to the construction of (or resistance to) the various meanings produced, we are left with only reductions of the contexts and cultures intended to be represented, exactly at the moment when tolerance and rereadings of history are most needed. Whereas the 14th Biennale barely reshuffles expected narratives of Architecture and modernity, the Peutinger Map appears in contrast like a magical “disciplinary cure.” Holding at once and in one long, interconnected, complex, and historical script the critical questions to powerfully recast Architecture within a highly complex field, it challenges reductive representations and invites instead the careful rereading of the past as a means to engage in more productive and meaningful representations of the world for the future.

Amale Andraos is the dean of Columbia University's Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, and a founding partner of WORKac. Her publications include 49 Cities, Above the Pavement, the Farm!, and the forthcoming Architecture and Representation: The Arab City.