On the greatness of this country, comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory asks, “Where else but in America could a poor black boy born in utter poverty in Gary, Indiana, end up being a rich white man?”1 This almost perfect joke along with “Smooth Criminal”—clearly Michael Jackson’s greatest hit (why the anti-gravity lean remains a footnote to the moonwalk will forever be a mystery)—were rattling around my head, and through the unfortunate sound system of my Toyota Corolla, as I cruised through the neighborhoods of south Gary in search of Jackson’s boyhood home.

Located a short detour off I-90, about forty-five minutes southeast of Chicago, in a quiet residential neighborhood, the 672-square-foot, three-room bungalow inconspicuously shares the street with abandoned homes as well as those persistently occupied. Built in 1949, it was constructed during the post–WWII industrial boom, along with most of Gary.2 Joe Jackson, the legendary patriarch of the family, made his way to Gary from Chicago in 1949 when he took a job at U.S. Steel. He and his future wife, Katherine, met shortly after he arrived, and the newly wedded couple moved into the house in January 1950. Their first child, Maureen, was born in May of the same year. Michael, the eighth Jackson child, was born on August 29, 1958.

The single-story clapboard home sits on a small, suburban lot and is little more than a squat rectangle with a pitched, tar shingle roof. The home was a tight fit, barely containing the prodigious Jackson clan until they made their break on the success of Michael and four of his brothers. J. Randy Taraborrelli, Jackson biographer and chronicler of celebrity life, writes:

Katherine and Joseph shared one bedroom with a double bed. The boys slept in the only other bedroom in a triple bunk bed; Tito and Jermaine sharing a bed on top, Marlon and Michael in the middle, and Jackie alone on the bottom. The three girls slept on a convertible sofa in the living room; when Randy was born, he slept on a second couch. In the bitter-cold winter months, the family would huddle together in the kitchen in front of the open oven.[^3]

[^3]: J. Randy Taraborrelli, <i>Michael Jackson: The Magic, the Madness, the Whole Story</i> (New York: Grand Central Publishing), 26.Michael recalls his home in less dramatic terms:

Our family’s house in Gary was tiny, only three rooms really, but at the time it seemed much larger to me. When you’re that young, the whole world seems so huge that a little room can seem four times its size. When we went back to Gary years later, we were all surprised at how tiny that house was. I had remembered it as being larger, but you could take five steps from the front door and you’d be out the back. It was really no bigger than a garage, but when we lived there it seemed fine to us kids. You see things from such a different perspective when you’re young.3

Joe Jackson’s infamous control of all things Jackson and his determination to bring the family success via the Jackson 5 left little time for fuzzy nostalgia, which is likely why the home didn’t leave much more than a basic spatial imprint on the young Michael. He was too busy neglecting his childhood, belting out Motown hits, and developing a boyhood (that is, boyhood without childhood) persona, one that has been forever hard to escape or control, even after his untimely death.

Throughout the 1960s, the Jackson 5 and Gary were on inverse trajectories, with the group making its way through the city’s clubs and the chitlin’ circuit while the city began its steady economic decline that continues to the present. By 1966 a Time magazine article had already pronounced Gary “the abandoned county.”4 Sited on the southern shore of Lake Michigan and hugging the western border of Indiana, the city was named after Elbert Henry Gary, co-founder (with J.P. Morgan) of U.S. Steel. The city’s fate has been intimately tied to those of the large steel production plants that have lined the lakefront since the city’s establishment in 1906. At its peak inhabited by nearly 180,000 people, Gary was an industrial hub serving as a cross-border suburb of Chicago. Like many of the cities along the shores of the Great Lakes, Gary served as a locus for black migration, both as a source of industrial jobs and an opportunity to flee the Jim Crow South. The result was a newly urbanized black population deeply tied to manufacturing labor and the fluctuations of the industrial economy.

Through the 1960s Gary joined much of the upper Midwest in economic decline, as U.S. Steel began a series of layoffs and the city was forced to confront racial segregation. In 1967 “white flight” began in earnest, in part because of the election of Richard G. Hatcher, the country’s first black mayor, a position he held for twenty years. Chronicling the history of Gary, historian S. Paul O’Hara writes of the politics surrounding layoffs at U.S. Steel, noting that in contrast to popular assumption, the underlying factor of Gary’s urban problems “almost always came down to race.”5 But by 1971, the Jackson 5 had recently released their ABC album, bringing them national pop-star status and allowing the family to move westward into a large estate in Encino, California.

Gary is usually thought of as the westernmost end of the Rust Belt, which stretches east toward and beyond Buffalo, New York. The cliché of the Rust Belt has become synonymous with the entire upper Midwest region and stands as the default specter when cities like Detroit, Akron, Cleveland, Erie, Buffalo, and Gary are conjured in the popular imagination. Today the city is home to an estimated 78,000 people (having lost more than 3 percent of its population in the last three years), of which 84 percent is black, with an overall poverty rate above 25 percent—three times the rate for the state of Indiana.6 Along with entrenched poverty, unemployment, and strict racial segregation, the cornerstone of Rust Belt-ism is an overwhelming surplus of abandoned homes and businesses, with which Gary is particularly blessed.

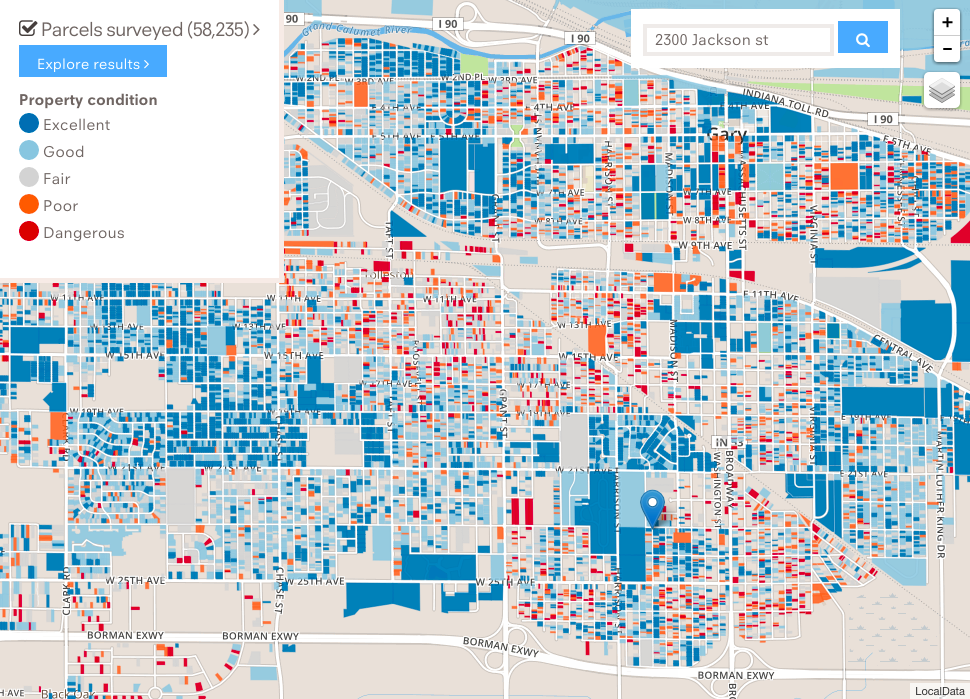

A two-year study conducted by ex–Chicago Mayor Richard Daley and graduate students from the University of Chicago to map and propose demolition plans for the city found 6,315 abandoned and 11,500 “blighted” homes (a term they choose not to qualify).7 Remarking on the results of the study, Daley stated, “There’s an extreme cost to demolition.” Forty million dollars, apparently. This bit of wisdom was matched only by Gary Redevelopment director Joseph van Dyk, who said in apparent surprise, “One thing that really stood out to me was the number of blighted buildings that were occupied.”8

At the time of Michael’s death, the Jackson home was owned by David Fossett, a cousin of the family. There was speculation that the powers-that-be in California would claim the home, uproot it from its neighborhood, and place it in a more prominent location with added tourist potential and better parking.9 But shortly after Michael’s death in 2009, the Jackson family helped renovate the house. The iron fence currently encircling the property was erected to maintain the grass and landscaping from fans and mourners, and in 2015 the house just to the south was purchased with the goal of making it into a small gift shop serving the many tourists who awkwardly flock to 2300 Jackson Street, likely on their way to and/or from Chicago. The two renovations are part of the Jackson Street of Dreams project run by the Fuller Center for Housing, an “ecumenical Christian housing ministry dedicated to eliminating poverty housing worldwide.”10 The project in Gary is funded in part by the Indiana Department of Corrections in hopes of reclaiming some of that “blighted” housing stock and providing homes to low-income Gary residents.11

After making my way through Gary and finding myself in front of Michael’s childhood home, the most overwhelming feeling was not one of eighties nostalgia, nor even sadness over Michael’s life and death, but of whiteness. Which is to say that standing in from of Michael’s home in Gary, Indiana, presented a certain (though admittedly unresolved) clarity to the ambiguous racial haziness that has come to define Michael’s own life, and which seems to be an indelible fact of contemporary American existence despite all the national conversations we are supposedly having. Which is not to say that Gary stands as a representation of black America, but that it shares certain affinities with places like Ferguson and Baltimore that have refocused the nation’s consciousness on the persistence of racial housing inequality (and therefore persistent inequalities, period) in a way that few recent events have.

Regardless of the pop-mecca hajj that the Jackson house offers, I felt like little more than a slum tourist. The manicured lawn and quaint renovation do not belie the fact that the Jackson home will likely have very little economic impact on the surrounding community. And that as much as the home stands for Michael, the Jackson 5, and the Jackson family, it also stands for the fact that Michael, like many of the jobs at U.S. Steel (and like me after taking a couple of photos), left Gary. For his part, Michael moved to California and became the racially and sexually amorphous pop idol who was adopted and co-opted across the world. It’s hard to look at the home and not assume that most of the visitors are much like me, happy to pull off the side of the road, but happier to get back in the car and get on with their trip.

The Fuller Center’s undoubtedly earnest goal of revitalizing Jackson’s street and its environs, while clearly emphasizing the tourist and economic potential of the Jackson home, illustrates the contentious relationship between poverty alleviation and economic stimulus. That tension is what permeates the experience of visiting the Jackson home. In more stark terms, that tension unfolds in the language used to describe cities like Gary. Homes are reconstituted as building stock, neighborhoods are reclassified as blight, and always in the background of revitalization stands the ominous presence of real estate development. Or, as the lawyers Martin E. Gold and Lynne B. Sagalyn more clearly state, “Blight findings have functioned as a cornerstone for condemnation takings since the severe urban decline in the middle of the twentieth century prompted governments at every level, throughout the country, to actively intervene in the real estate market. Elements of blight, and then the term itself, became a foundational basis for this governmental intervention.”12 Blight is a legal designation freeing local governments and private business from the fetters of property ownership, opening the door to imminent domain and corporate re-privatization.

The positive economic stimulus that comes from successful urban revitalization quickly takes on the more fraught identity of gentrification when it is actually successful. Or, to rephrase this as a question that applies more directly to Gary: What might urban revitalization look like without a coherent plan for generating employment in an area that sits precariously outside the reach of conventional real estate development? The terms revitalization, renovation, real estate development, and gentrification can be read as synonymous, yet each one stands in stark contrast to the swaths of black and low-income neighborhoods that are outside the purview of real estate developers and the young white professionals such developers cater to.

The crux of any revitalization program remains the enduring dream of home ownership. And yet the current state of Gary is a reminder of the entrenched racial biases that continue to permeate the process of black home ownership and wealth transfer. Thomas M. Shapiro traces this fact back to the historic obstacles to securing black wealth, most importantly the fact that “family inheritance, especially financial resources, are the primary means of passing class and race advantages and disadvantages from one generation to another.”13 Shapiro calls this type of wealth transfer “transformative assets,” meaning inherited wealth has the power to “lift a family beyond their own achievements.”14 It should be no surprise that the key vehicle developing transformative assets is home ownership and the ability pass on home equity. The old adage “it takes money to make money” takes on different resonance in reflection of 250 years of slavery, segregation, redlining, and adjustable rate mortgages each designed to keep black Americans poor and disenfranchised.

The current rental rate for Gary’s residents below the poverty level is above 70 percent, double that of those above the poverty level. This speaks to a long history of housing and mortgage policy discrimination that has left home ownership for black Americans at 42.4 percent nationally, almost 30 percent lower than for white Americans. It is the same mechanism that made “white flight” possible.15 The dream of owning a home pales in comparison to the reality of abandoning it at will, and with so little financial hardship, that leaving a home behind becomes a viable option.

The (ongoing) history of racist housing policy percolated through the 2008 financial crisis. In his essay on reparations, Ta-Nehisi Coates concludes by referencing the sociologists Jacob R. Rugh and Douglas S. Massey on the most recent foreclosure crisis: “Among its drivers, they found an old foe: segregation. Black home buyers—even after controlling for factors like creditworthiness—were still more likely than white home buyers to be steered toward subprime loans. Decades of racist housing policies by the American government, along with decades of racist housing practices by American businesses had conspired to concentrate African Americans in the same neighborhoods.”16

The current effects and recurrent tragedy of urban poverty and unstable housing in predominantly black neighborhoods has played out in dramatic form over the last fifteen months, particularly since Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager, was shot in Ferguson, Missouri, by a white police officer in August 2014. Since then, Americans have been privy to a steady stream of videos showing white cops beating up and killing black students, black women, and black unarmed men. Recently, the fallout and lack of justice has left the cities of Baltimore and Ferguson ablaze. The events shed light on large portions of urban America that remain frustratingly out of sight—that is, until they are thrust onto our TVs when they are on fire and militarized police forces are called in to enforce peace. The usual question asked among talking heads and right-wing blowhards is, “Why do they burn their own cities?” Michael Eric Dyson answers simply, “Without a brick tossed or a building burning, we are hardly confronting the hopelessness of the future for these young people.”17 He could have just as easily answered such a lame question with one of his own: Why are you surprised when people destroy something that you have already said has no value?

Like almost everything related to or involving Michael Jackson, his childhood home is hard to pin down. It sits uncomfortably between the two poles of Michael’s own life, begging visitors to remember him as the child star of the Jackson 5 and the eighties King of Pop, not the man-boy of Neverland Ranch desperately hoping to relive the childhood he never had. Neverland, a bloated nightmare of gilded excess, stands, like Michael, as the larger-than-life version of the American Dream, a visual reminder of the bootstraps myth that with hard work and a little talent each and every American can embody Dick Gregory’s painful joke.

His former home in Gary also stands as one of the classically American roadside formations, meant to be consumed from the relative safety of an automobile. It exists somewhere between side-street tchotchke, cultural attraction, and grave marker, like a strange hybrid between the Lorraine Motel and Graceland. And it sits as a renovated tourist attraction, a sparkling white house set within a neighborhood where little else shines, a stark reminder of the racist history of home ownership and the urban fallout it continues to precipitate.

Beyond the desire for reinvestment and an anchor for future redevelopment, the childhood home of Michael Jackson can serve another purpose. Michael’s house can continue to do what it already does—highlight the fact that the urban policies and mortgage funding structures propping up a large portion of the white middle class have fundamentally failed black Americans. The home is a clear signal that housing functions as one of the key signifiers of inequality and segregation. And in that sense, the home is a perfect monument, taking the universal appeal of Michael Jackson to displace his eager fans into a useful confrontation with a neglected America that remains shockingly pervasive.

-

“VH1 News Presents: Michael Jackson’s Secret Childhood,” Silent Lambs, accessed October 30, 2015, link. ↩

-

House construction data and size from “2300 Jackson Street, Gary, Indiana,” Trulia, accessed October 30, 2015, link. Gary home construction statistics from “Gary, Indiana (IN) Poverty Rate Data,” City-Data, accessed October 30, 2015, link. ↩

-

Michael Jackson, Moonwalk (New York: Doubleday, 1988), 6. ↩

-

The history of Gary cited here largely comes from Paul S. O’Hara’s book on the city. Paul S. O’Hara, Gary: The Most American of All-American Cities (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011), 124. ↩

-

O’Hara, Gary, 148–149. ↩

-

See “State and County Quick Facts, Gary (city), Indiana,” United States Census, accessed October 30, 2015, link. “Gary, Indiana (IN) Poverty Rate Data,” City-Data, accessed October 30, 2015, link. ↩

-

Melissa Harris and Corilyn Shropshire, “Daley turns focus toward Gary,” Chicago Tribune, February 17, 2013, link. ↩

-

Mike Krauser, “Gary Survey Finds 6,300 Vacant Homes; 550 Vacant Businesses,” CBS Chicago, February 18, 2015, link. ↩

-

“Jackson's family home in Gary, Ind., may be relocated,” Los Angeles Times, June 30, 2009, link. ↩

-

“About Us,” The Fuller Center for Housing, accessed October 30, 2015, link. ↩

-

“Indiana Department of Corrections Commissioner Excited About Gary Project,” The Fuller Center for Housing, accessed October 30, 2015, link. ↩

-

Martin E. Gold and Lynne B. Sagalyn, “The Use and Abuse of Blight in Eminent Domain,” Fordham Urban Law Journal 28 (2011): 1119–1173. ↩

-

Thomas M. Shapiro, The Hidden Cost of Being African American (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 61. ↩

-

Shapiro, The Hidden Cost of Being African American, 11. ↩

-

“U.S. Census Bureau News,” U.S. Department of Commerce, October 27, 2015, link. ↩

-

Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations,” the Atlantic vol. 313, no. 5 (June 2014), link. ↩

-

Michael Eric Dyson, “Goodbye to Freddie Gray and Goodbye to Quietly Accepting Injustice,” New York Times, April 29, 2015, link. ↩

Jordan H. Carver is a contributing editor to the Avery Review and a Henry M. MacCracken doctoral fellow in American Studies at New York University.