The following essay will appear in Climates: Architecture and the Planetary Imaginary, published this spring by the Avery Review and Lars Müller Publishers.

What Sort of Story Is Climate Change?

Gaïa Global Circus takes aim at the deficiency of our emotional repertoire for dealing with the climate crisis—a condition that this theatrical event’s conceiver Bruno Latour describes as the “abysmal distance between our little selfish human worries and the great questions of ecology.”1 This experimental play can be seen as a confluence of two areas of interest: On the one hand, the director and artists sought to reanimate the theater’s historic connection with the cosmos, and on the other, the public scholar questioned how he might best address environmental disasters beyond the usual apocalyptic cultural imaginary. These two groups share a sense that the great challenge facing the debate around climate today is one of new forms and forums of eco-political engagement. And both also address a shared concern: If the threats are so serious, if we worry once again that the sky might be falling on our heads, how is it that we are all so little mobilized?

In her analysis and critique of the abstract images produced by experts in the discourse of climate change, Birgit Schneider elaborates on problems of perception as well as of scale. People observe daily weather changes, she notes, but they do not perceive climate—which is, according to its modern definition, a statistically created, abstract object of investigation with a long-term assessment period. Furthermore, people can experience local weather but not the global effects of climate change, which would require no less of them than to perceive the world as a whole.2 How do we think about something as intangible and invisible as climate? What are the aesthetics and tone of narrating climate change, and to what ends? If environmental issues are un-representable in their scale, their ubiquity, and their duration, then perhaps it falls to works of art (which are still works of thought) to present them to the senses.3

Gaïa Global Circus belongs to the genre of the arts of climate change. This rapidly emerging body of work explores the interplay between climatic knowledge and aesthetic experience to engage with the temporal and scalar dissonances of the issue at stake, and to acknowledge and deal with the effects of environmental processes upon life. Such practices deploy a range of aesthetic formats to explore our chaotic relationship with Gaia, be they Olafur Eliasson’s ice installations (the most recent of which is at the 2015 Paris Climate Change Conference), Ursula Biemann’s video essays, or the Climate Changed graphic novel by Philippe Squarzoni, to name only a few. Latour and his collaborators envisaged a play that commands a new approach to science, politics, and nature by combining varying tones of tragedy, comedy, and ritual.4 Theater, by their estimation, is uniquely capable of exploring the dramas and emotions not elucidated in public discourse. Their intention was to make sensible our thing-world by creating a collective aesthetic experience, which in turn implies the possibility of new configurations of climatic publics. Their concerns resonate with Ulrich Beck’s “emancipatory catastrophism,” the term by which he proposes that we can and should turn the question on climate change upside down—not to ask “what can we do for climate change?” but rather, “what is climate change good for?”5

Political Arts: From Abstract Knowledge to Collective Aesthetic Experience

Latour proposes that climate change calls for a new worldview, one that includes the figure of Gaïa as a new personage on the theater of the world. In his view, the assumed divide between nature and society—and the accompanying focus on deanimate, disembodied, undisputed reason—has led directly into the current ecological crisis. We do not live on a “Blue Marble,” insofar as that famous image of our planet symbolizes an objective, holistic, impersonal earth made visible by our own technological achievements. Such metaphysics of technological progress, Latour argues, should now be countered by a redefined assemblage of values, so as to extend beyond the critique of the modern objectification of the Earth to a new ecological belief-system in the embodiment of Gaïa. This carries a scientific as well as a mythological dimension—Gaïa derives from technological processes of modeling and measurement but also incorporates an abundance of mythological connotations, as its name evokes the Greek goddess of Earth. Gaïa is an “odd, doubly composite figure… the Möbius strip of which we form both the inside and the outside, the truly global Globe that threatens us even as we threaten it.”6 Latour cites The Revenge of Gaïa (2006), in which James Lovelock discusses positive feedback “tipping points” leading to significant and irreversible climate system changes.7

Beyond the accumulation of scientific knowledge, Gaïa embodies questions of representations, of what the issues are and where we stand vis-à-vis those issues. For Latour, “the Big Picture is just that: a picture. And then the question can be raised: in which movie theatre, in which exhibit gallery is it shown? Through which optics is it projected? To which audience is it addressed?”8 Beyond the big picture, the absorption of this concept of Gaïa in the public consciousness requires a new and different rhetoric that connects political ecology with the energy of collective aesthetic experience. Latour calls for a new worldview that might “counter a metaphysical machine with a bigger metaphysical machine.” He adds: “Why not transform this whole business of recalling modernity into a grand question of design?”9 His response calls for crafting the “political arts”—an experimental method for conceiving and responding to the problem of climate change. If politics is the art of the possible, then the multiplication of the possible requires a reconnection with the many available formats of the aesthetic. The project of the political arts fits into Latour’s broader quest for a new eloquence with which to engage political ecology. In his books Making Things Public (2005) and Politics of Nature (1999), both of which include the word “democracy” in their subtitles, Latour explores the gap between the importance of the politics of representation in politics and ecology and the narrow repertoire of emotions and sensations with which we understand these issues. He asks what would happen if politics revolved instead around disputed things, atmospheres, natures, and what techniques of representation might help make them public. In his recent book An Inquiry into Modes of Existence (2013), Latour demands nothing less than to overcome the modern preoccupation with objective scientific truth and to rediscover the plurality of vastly different modes of existence (like religion, morality, or law). Latour repeatedly states the reason for which this is needed at this very moment: “Gaïa approaches.”10

The Theater: Making Climate Public

Latour argues that the assembly, the model of political accord organized according to a very particular architecture (for example, Étienne-Louis Boullée’s Cenotaph for Isaac Newton) has disappeared. Which assembly, then, are we in now? What spaces could stage a totality, especially when that whole is opaque, fragmented, contradictory? In Reassembling the Social, Latour outlined the panorama as a historical visual practice and space that stages such a sense of wholeness. From the Greek pan- (all) and -rama (spectacle), the panorama is a view of totality. Installed in rotundas, panoramas were immense 360-degree paintings that hermetically surrounded the observer. From a darkened central platform, the observers found themselves completely enveloped in visual illusions illuminated by concealed lighting. These “sight travel machines” transposed the visitors into the image, be it simulations of distant lands, familiar cities, or catastrophes of nature or wars.11 Struck with enchantment in the middle of a magic circle, the spectator is sheltered from unwelcome distractions all while being immersed in a foreign landscape. Latour found these contraptions quite powerful, particularly as they solved the question of staging totality and nesting a range of scales, from the micro to the macro, into one another. However, he also points to their limitations, in that “they don’t do it by multiplying two-way connections with other sites.” A panorama designs a picture with no gap in it, “giving the spectator the powerful impression of being fully immersed in the real world without any artificial mediations or costly flows of information leading from or to the outside.”12

The limits of the panorama as a form of composing totality led Latour to explore other modes of representation, particularly those that stage their own technology and capitalize on their distance from the real. In describing controversies and scientific evidence, Latour has worked on what he calls “the theater of proof”: how evidence is made convincing in the eyes of the witnesses. This is not to jeopardize the actual qualities of the evidence but rather to show what motivates scientists to develop effective evidence. This research in turn interested Latour in the reverse process: how the stage might help scientists, especially climatologists, follow the threads of what makes convincing proof—a crucial issue at a time when climate skeptics have such influence on public opinion.13 Hence the idea that he could explore, onstage, all the dissonances of climate change with an “older and more flexible medium than philosophy.” For Latour, “only the theater can afford to explore the range of passions corresponding to contemporary political issues.”14

How Do We Talk When We Talk in Climate Theater?

The theater is thus the collective aesthetic equivalent of the Parliament or the Congress. It appropriates the technologies of the “image machine” to place the story of climate change, a story that is difficult both to tell and to hear, at the center of the “Theater of the World.” The theater is neither theory nor teaching; it is a practice that makes possible through the medium of the stage a thought experiment that is done in public, not just in the head.15 This form of communication addresses environmental matters by sharing them in full scale and in real time with an audience that is assembled in small collectives. It responds to the accelerationist temporality of climate change, a phenomenon well represented in recent short videos on human-induced climate change. One such example is Welcome to the Anthropocene, a three-minute roller-coaster ride through the latest chapter in the story of how one species has transformed a planet. Commissioned by the London Planet Under Pressure conference, Welcome to the Anthropocene provides a data visualization of the state of the planet. It opens at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. As the camera swoops over Earth, viewers watch the planetary impact of humanity: cities, roads, railways, pipelines, cables, and shipping lanes, until finally the world’s planes spin a fine web around the planet.16 Contrary to such representations of acceleration, Gaïa Global Circus slows down thought to ground it in the immediacy of the present. Latour’s piece also adopts a different narration tone. Rather than a foretold tragedy as it unfolds in disaster movies and short films, Gaïa Global Circus is a tragicomedy that blends those opposing but complementary genres with decorum, in order to prevent the listeners from falling into the excessive melancholy of what is at stake.

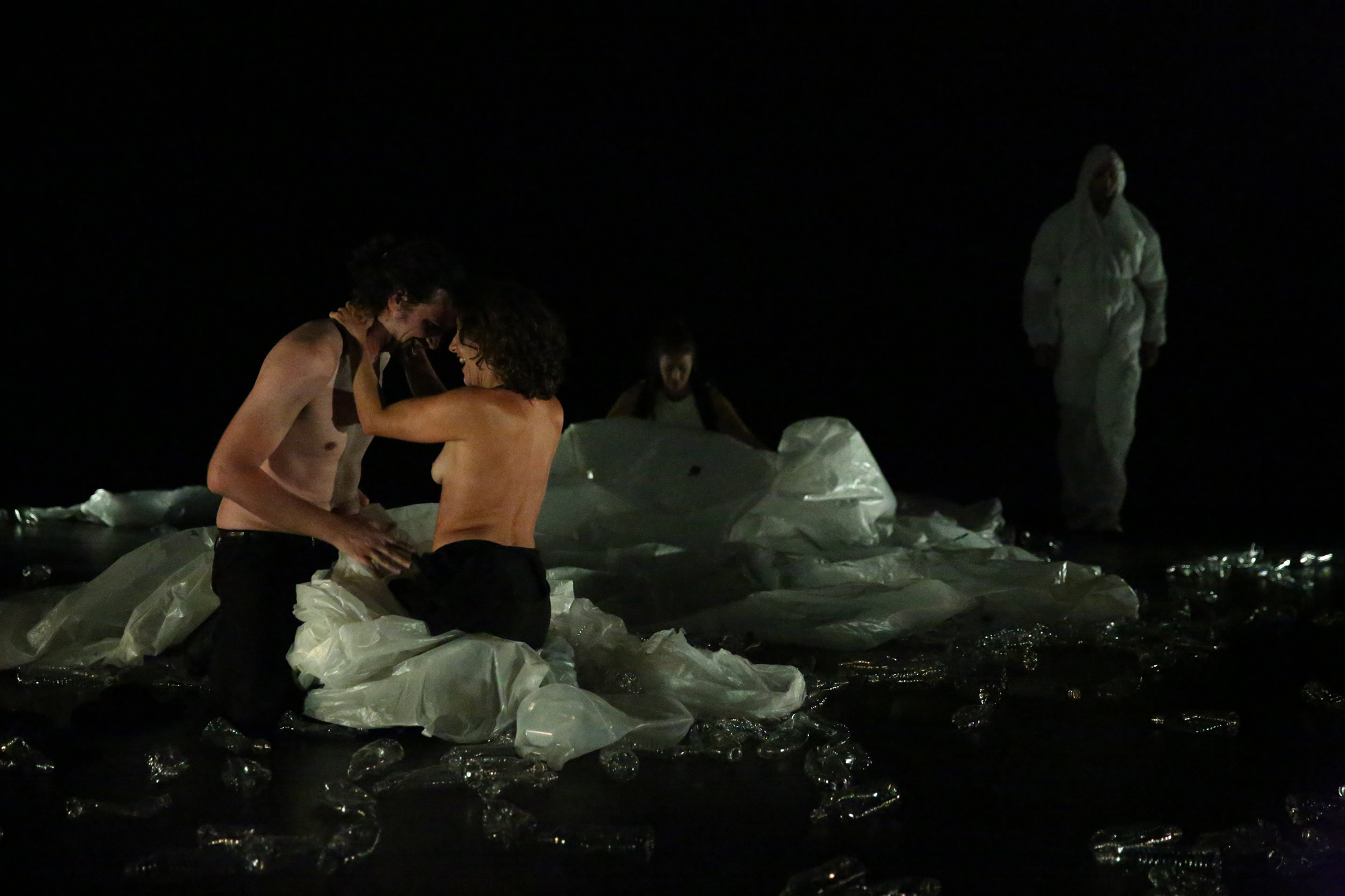

With monsters, storms, a modern-day Noah, scientists, and divinities onstage, the theater is the setting in which the performance and speech of nonspeaking and nonhuman entities operate as devices of estrangement. Gaïa Global Circus counters the familiarity of disaster satellite images that numb the senses into a “feeling of vaguely blasé nonchalance.”17 The piece animates an era when humans recognize their transformation into a climatological entity, all while foregrounding the frictions and dissonance of cross-scalar, multispecies, and intertextual thinking. It is a show that reflects on the tensions between the cacophony of human positions on ecology, our own contradictions in relating to them, and what encompasses and surpasses them. These various threads trace, watch, project, worry, make astonishing discoveries, and knit together the voice of Gaïa—a voice that has many interpretations, because it emanates from a complex and non-unified figure. Gaïa Global Circus animates the earth in an era when humans recognize their transformation into a climatological entity, all while hindering the possibility of a simple identification with the characters in the play. It invites the audience to engage the performed actions and utterances on an aesthetic and cognitive plane, rendering them astonishing in intellectually challenging and sometimes frightening ways.

Faced with this inaudible speech, the theater intervenes with its proper tools: thought experiments in the form of scenic and mental images are active fictions of a world yet to come. This model of the theater resonates with Donna Haraway’s concept of “worlding” as a process of actively reimagining a non-anthropocentric world. “These knowledge-making and world-making fields,” Haraway observes, “inform a craft that for me is relentlessly replete with organic and inorganic critters and stories, in their thick material and narrative tissues.”18 The model of the world that Gaïa Global Circus projects moves away from the dominant discussion of technical fixes for the climate, which focus on the improvement of technology, information, and policy incentives as means to “manage” or even “reverse” climate change. Rather, it proposes to advance new hypotheses and cultivate thinking about what current technologies, theories, or habits can’t yet solve. It is not “the job of theatre to find a solution,” Latour notes, but to play with “the dialectic between philosophical reasoning and theatrical experiment… It is a dance, rather than an argument.”19

A New Personage Has Entered the Theater of the World

In an article titled “La Non-invitée au Sommet de Copenhague,”—roughly translated as “Who Wasn’t Invited to Copenhagen?”—Michel Serres points to the one empty seat at Copenhagen’s Parliament of Things: that of Gaïa. He wonders how to make it possible for her to sit, speak, and be represented. What is the Gaïa equivalent of Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan’s frontispiece? The challenge of governing the climate is that we are addressing the global without a world state, requiring a form of representation to think through the new geopolitics of climate change.

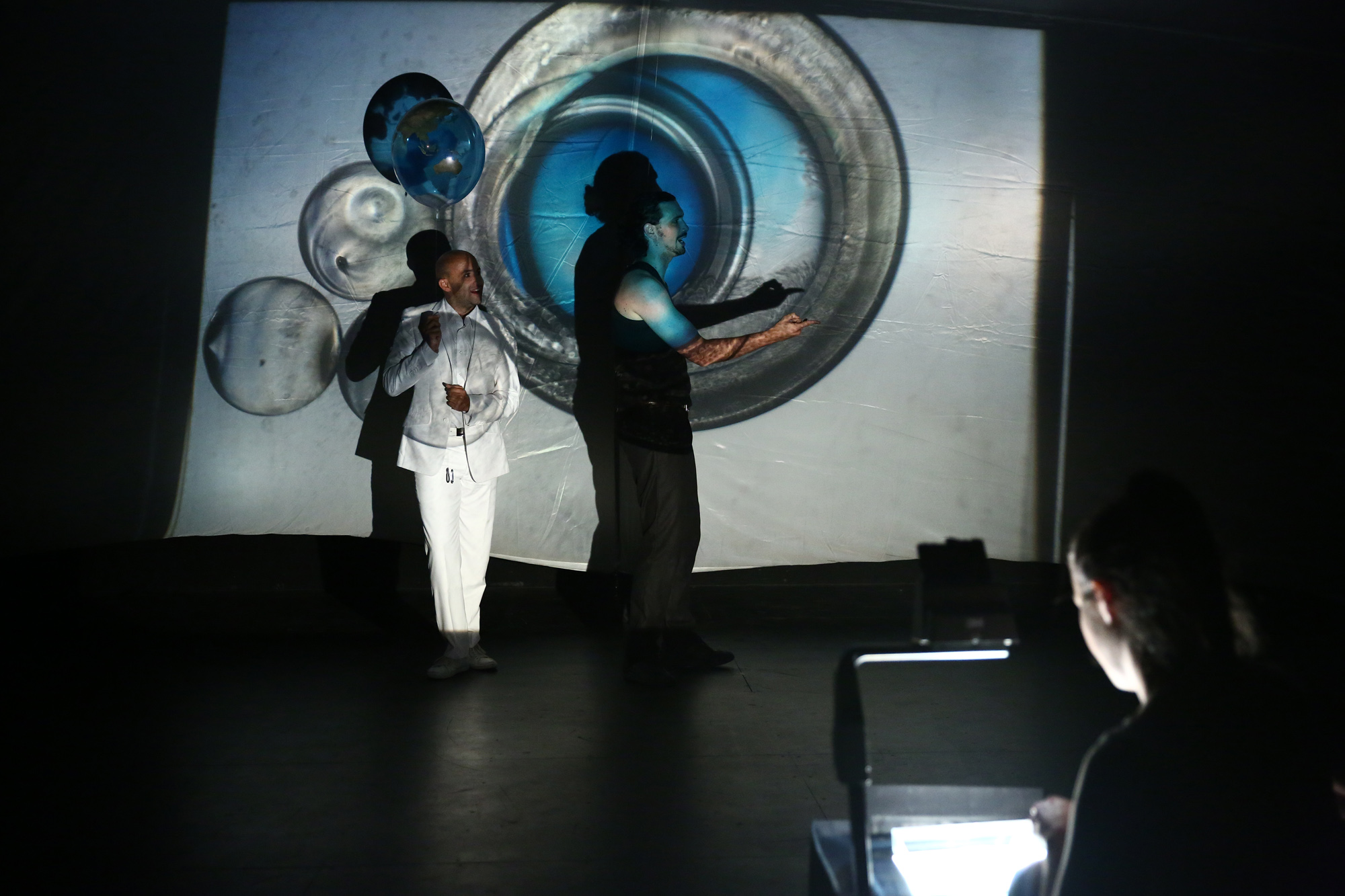

Gaïa Global Circus responds to this provocation by borrowing from techniques of the Baroque theater. It deploys the ancient theater of shadows and more contemporary optical machines to imagine a theatrum mundi for our time. The scenography makes sensible the scalar dissonance between the human and nonhuman, and explores a possible relationship with the environment in which the human is no longer the center. The play takes place in a circus tent, with the audience occupying one part of the arena on stepped rows of seats. Both actors and spectators are under a canopy on which different atmospheres are projected—similar to other world representations like a geodesic dome or planetarium. The stage becomes an actor in its own right. It seeks to capture the issue of an environment that no longer surrounds us because it has become a player on the world stage. The centerpiece of the décor is a translucent canopy floating in the air and suspended by helium balloons. This mainsail device (measuring some 20 by 25 feet) enables the actors to transform the stage area at every moment, as it can be moved like a canopy over any portion of the theater. When a storm from what seems like the end of the world rumbles through, the floating canopy envelops the audience, as a comfort object or a security blanket. Both a model of the world and a wonder object in itself, the “flying tent” is both an effort to put the world onstage and an attempt to question our perception of nature. Mobile, changing, and unpredictable, this décor-actor is a living object moved by the actors, which transforms the stage and constantly produces atmospheres and climates. At every performance, this flying machine seeks a collective experience of another relation to our common world, at the scale of the theater. “In a way,” Latour notes, “this canopy screen is the lead actor in the play.”20

Just as a geologist can hear the clicks of radioactivity, but only if he is equipped with a Geiger counter, we can register the presence of morality in the world provided that we concentrate on that particular emission. And just as no one, once the instrument has been calibrated, would think of asking the geologist if radioactivity is “all in his head,” “in his heart,” or “in the rocks,” no one will doubt any longer that the world emits morality toward anyone who possesses an instrument sensitive enough to register it.

—Bruno Latour, An Inquiry into Modes of Existence

Why is Gaïa the lead actor in the play? Because global warming, the most important event concerning us (according to climatologists and environmentalists) is also the symptom of the emergence of this new controversial figure called Gaïa. Gaïa Global Circus appeals to affective, aesthetic, and media practices in an effort to address the cognitive dissonance between the scale of the issues to be addressed and that of the set of emotional and experiential states that are associated with the task. It is one appeal for an aesthetic practice to engage the contemporary pressing matters of the world. “If theatre is to become, once again, the theatre of the globe,” Latour observes, “then it must re-learn, like Atlas, how to carry the world on its shoulders, both the world and all there is above it.”21 It must relearn the pleasure of a collective aesthetic experience of connecting our individual dynamics of hope, fear, and desire to a larger scale of environmental, planetary, and ultimately cosmic dynamics of the same order. At the core of Gaïa Global Circus, you find a fundamental question about the fabric of reality, the forms of knowledge that frame that reality, and the impossibility of ever fully knowing or comprehending it. Yet, to quote Isabelle Stengers, a philosopher and longtime interlocutor of Latour’s, Gaïa has the urgency to induce thinking and feeling in a particular way.22

-

Laura Collins-Hughes, “A Potential Disaster in Any Language: ‘Gaïa Global Circus’ at the Kitchen,” New York Times, September 25, 2014, link. ↩

-

Quoted in Antonia Mehnert, “Climate Change Futures and the Imagination of the Global in Maeva! by Dirk C. Fleck,” Ecozone, vol. 3, no. 2 (2012): 28. ↩

-

The collective work was undertaken with Chloé Latour and Frédérique Aït-Touati (directors), Claire Astruc, Jade Collinet, Matthieu Protin, and Luigi Cerri (actors), and Pierre Daubigny (playwright). ↩

-

Ulrich Beck, “How Climate Change Might Save the World,” Development and Society, vol. 43, no. 2 (2014): 169–83. ↩

-

Bruno Latour, An Inquiry into Modes of Existence: An Anthropology of the Moderns (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), 9f. ↩

-

Lovelock defines Gaïa as “a biotic-planetary regulatory system. Over 30 million types of extant organisms, descendant from common ancestors and embedded in the biosphere, directly and indirectly interact with one another and with the environment’s chemical constituents. They produce and remove gases, ions, metals, and organic compounds through their metabolism, growth, and reproduction. These interactions in aqueous solution lead to modulation of the Earth’s surface temperature, acidity-alkalinity, and the chemically reactive gases of the atmosphere and hydrosphere.” See James Lovelock, <The Revenge of Gaia: Why the Earth Is Fighting Back and How We Can Still Save Humanity* (London: Penguin Books, 2007). ↩

-

Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 187. ↩

-

Latour, An Inquiry into Modes of Existence, 23. ↩

-

Latour, An Inquiry into Modes of Existence, 13. ↩

-

Stephan Oettermann, The Panorama: History of a Mass Medium (New York: Zone Books, 1997). ↩

-

Latour, Reassembling the Social, 187. ↩

-

Gaïa Global Circus. ↩

-

Bruno Latour, A propos de Gaia Global Circus (GGC) Réponses à quelques questions fréquentes (FAQ), link. ↩

-

Gaïa Global Circus. ↩

-

Frédérique Aït-Touati and Bruno Latour, “The Theatre of the Globe,” Exeunt, February 13, 2015, link. ↩

-

Donna Haraway, “SF: Science Fiction, Speculative Fabulation, String Figures, so Far,” Pilgrim Award Acceptance (2011), link. ↩

-

Jonas Tinius, “‘All the World’s a Stage?’ A Review of Bruno Latour’s Gaïa Global Circus,” March 3, 2015, link. ↩

-

Bruno Latour, Frédérique Aït-Touati, and Chloé Latour, “Material for Stage Writing Within the Framework of the Project: Gaïa Global Circus,” trans. Julie Rose (May 2011), link.

Gaïa Global Circus, project by Bruno Latour, play by Pierre Daubigny, directed by Frédérique Aït-Touati and Chloé Latour, Compagnie AccenT and Soif Compagnie, at The Kitchen, 2014. Photo © Paula Court. Courtesy of The Kitchen. Gaïa, the Urgency to Think and Feel

-

Aït-Touati and Latour, “The Theatre of the Globe.” ↩

-

Isabelle Stengers, “Gaia, the Urgency to Think (and Feel),” Os Mil Nomes de Gaia (September 2014), link. ↩

Rania Ghosn and El Hadi Jazairy are partners of DESIGN EARTH. The practice engages the geographies of technological systems to open up a range of aesthetic and political concerns for architecture and urbanism. DESIGN EARTH’s work has been recognized with several awards, including the 2015 Jacques Rougerie Foundation’s First Prize.

Ghosn and Jazairy hold doctor of design degrees from Harvard University Graduate School of Design, where they were founding editors of the journal New Geographies. They are authors of the recently published Geographies of Trash (Actar, 2015), for which they received the 2014 ACSA Faculty Design Award. Some of their recent work has been published in Journal of Architectural Education, MONU, San Rocco, Bracket, Perspecta, and Topos.