The Asklepios 8 tower is particularly beautiful at sunrise. It is best seen from the westernmost bridge that crosses the Rhine in Basel, a small city in Switzerland—population 160,000—that stands at the borders with both Germany and France. Standing at the edge of the water with the sun directly opposite, the rectangular silhouette of the building seems subtracted from its surroundings, its bright glass façade with all blinds down creating a stark white volume contrasting with the morning sky. Seen during the early evening, all blinds up and the glass’s transparency at its maximum, the tower seems to dematerialize into the air and water around it. And at night, illuminated from within, it shines as a beacon for those who enter or leave the city.

Designed by Basel-based office Herzog & de Meuron and completed in 2015, the building is the newest addition to the Novartis campus, the pharmaceutical giant’s world headquarters.1 A closed campus at the edge of the city, alongside the French border, the Novartis campus is famous for its architecture. With a masterplan originally developed by Vittorio Magnano Lampugnani in 2001, it boasts buildings by Diener & Diener, Peter Märkli, Rafael Moneo, Tadao Ando, David Chipperfield, Frank O. Gehry, and SANAA, among others. While the campus is closed-off, Herzog & de Meuron’s building resolutely opens the compound to the Rhine, getting as close to the water as it can and using the gently sloping bank to boost its height. Rising to 207 feet, it is the tallest of the Novartis buildings, despite the masterplan’s recommended 77-foot limit.

By Basel standards, the building is most definitely a high-rise, as is any structure in the country that rises above 98 feet—a Hochhaus, in German, which literally translates to high building. For Herzog & de Meuron, this definition is taken literally. The architects state how “the distinctive volumetric structure of Asklepios 8 makes it a high building rather than a high-rise that typically repeats identical layers from top to bottom.”2 And indeed, the tower’s most striking features are a triple-height building core that connects two more conventional modules (a six-story module at the bottom and a seven-story at the top), and its prodigious ability to appear and disappear throughout the day. This effect is achieved with an ingenious glass façade whose panel system, rather than being attached to a load-bearing steel frame like a traditional curtain wall, is instead set behind two layers of load-bearing elements, retreating into the shade of cantilevered roof extrusions on each floor.

The result is a shaded skin, impeded from reflecting its surroundings and instead allowed to become fully transparent. The two layers of load-bearing poles enhance the apparent lightness of the structure, which seems to be suspended by thin wires. During the day, white blinds are drawn homogeneously on different sides of the structure. At night, though, the rhythmic sequence of the office floors is more dramatically interrupted by the building’s triple-height core, and all of the building’s interior is visible to the city. Asklepios 8 opens itself to the city—and delicately, but resolutely, makes its mark on it.3

The tower’s positioning and massing align it with the other campus buildings, continuing their orthogonal orientation and echoing their proportions. It also extends the campus, making the first of future additions to the Rhine front as the campus expands, and connecting to a public promenade that will, for the first time, allow passersby to access the Novartis waterfront. Upon its projected completion in 2016, promenade visitors will also be able to access a public restaurant and café on its lower floor. But for now, the building remains best seen from the westernmost bridge of the city, Dreirosenbrücke.

If, while standing on that bridge, you turn east, you’ll see another recent Basel addition: a white, stepped-back tower that cuts through the skyline, its shape and height strikingly different from the city fabric that surrounds it. Rising to 584 feet, it is Roche Building 1, the first new building planned for the campus extension of Hoffman-La Roche, another pharmaceutical giant that has its headquarters in Basel. 4 Completed in 2015, it is also designed by Herzog & de Meuron, and it is the tallest building in Switzerland, at least until its near-identical (but taller) companion—Roche Building 2, designed by the same architectural office and slated to be completed by 2021—is erected.

Unlike Asklepios 8, Roche Building 1 dramatically rises above its surrounding buildings. Its massive height is scarcely mitigated by its trapezoidal shape: the west façade progressively steps back all the way to the top of the 41-story tower, while the east façade is slightly slanted. This high-rise, in contrast with Asklepios 8, does repeat identical layers from top to bottom: office spaces continue all the way to the top, where a canteen and two levels of galleries displaying samples of the company’s art collection also provide sweeping views of the city. The building is off-limits to the general public, however, with Roche CEO Severin Schwan making clear that “it brings us nothing if we have people rushing in droves to the tower and shooting souvenir photos there.”5

The rhythmical façade is punctuated by alternating ribbon glass windows and white balustrades. The window shades, when closed, are also white, and their combination with the balustrades offers curious transformations—when all shades are closed, they transform the building into a haunting monolith, but when closed in scattered clusters, they give the tower the appearance of a giant smile from which several teeth are missing. Herzog & de Meuron claim their inspiration for the design came from the earliest buildings on the Roche campus. Constructed in the 1930s, these were designed by Swiss architect Otto Rudolf Salvisberg, who as company architect also planned many of Roche’s factories and industrial outposts throughout Europe. The original complex is a low-rise functionalist gem, which at the time was installed in what was a periphery of the city, flanked by an affluent residential neighborhood leading to the riverfront.

Almost a century later, the affluent residential neighborhood remains, and the Roche campus is anchored to the east by Mario Botta’s Jean Tinguely Museum, whose main patron is the pharmaceutical company. Several residential buildings surround the Roche grounds and sprawl outward until they reach the border of the city: a highway viaduct, and the Schwarzwaldbrücke, Basel’s easternmost bridge over the Rhine. Unlike the Novartis campus, the Roche campus has been engulfed by the city on all sides, and its location on the right bank of the Rhine is directly across from the city’s historic center on the opposite bank. This makes Roche Building 1 extremely visible from all sides. In fact, visibility studies for the building seem to have been conducted methodically, with scientific precision—the tower can be seen from all major intersections, bridges, squares, and entry points into the city, from the train stations to the nearest German city across the border. Because Basel lies comfortably nested in a valley, the tower can even be seen from the hills around it, miles and miles away, widely surpassing the height of Morger Degelo’s 2003 Messe Tower and Basel’s celebrated medieval cathedral. There’s no escaping it.

Its blunt, almost uncomfortable white presence, however, could not have been foreseen by looking at the project’s early sketches and visualizations, which portray the tower as a glassy expanse that rises into the sky, reflecting its surroundings and thus annulling its presence. Nor would it be guessed by reading the architect’s project description, which states that “depending on the light reflected on the façade, the balustrades and windows merge together into a light volume which dissolves towards the sky.”6 Since the project was first announced, public reactions to the building have been fiery and passionate, with much being written about the project and its undeniable impact on the city and its direct surroundings.

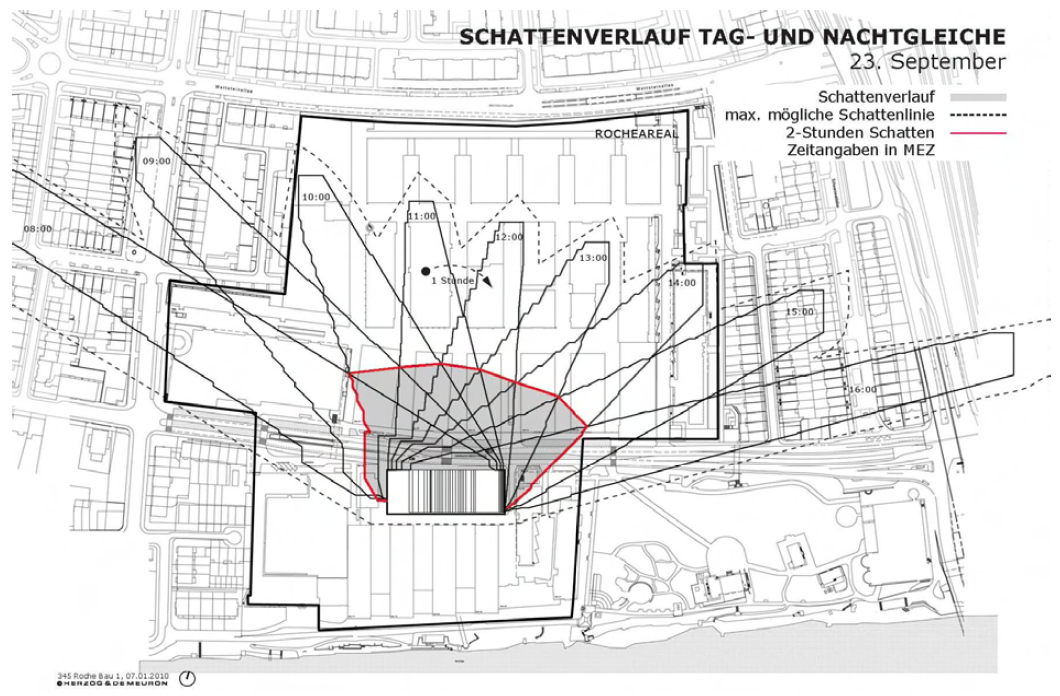

Some of the reactions were collected and displayed recently at the Swiss Architecture Museum, in the excellent 2014 exhibition, Constructing Text: Swiss Architecture Under Discussion, which analyzed several building projects in Switzerland and the impact architectural critique had on them.7 In the case of Roche Building 1, critics’ opinions were of little impact, as were the many petitions officially filed by neighborhood residents and local institutions who sought to fight the building’s erection. Once the tower passed the mandatory shadow study, proving that most of its shadow would fall on Roche grounds at all times, and received a resigned comment from the local Stadtbildkommission (commission on the image of the city) regarding its insertion in the neighborhood, it had only to receive a final evaluation from the building and urban planning commission of the Basel City canton.8 Strikingly, the 2010 report to the canton’s Grand Council passively resorted to general observations, admitting that “skyscrapers are a trend” and “are not built to make the city more beautiful” but rather for densification purposes. “It is not unimportant who builds such a landmark building,” and the commission states the importance of doing their best to keep a company such as Roche in the city.

The industrial zoning of the Roche grounds allows building heights up to 131 feet, with any additional height subject to a specific vote by the Basel City canton’s Grand Council. The council ended up approving Herzog & de Meuron’s radically tall, 584-foot skyscraper scheme, persuaded by the report, which minimizes the tower’s impact, given that “when it gets thinner at the top it has less effect on the cityscape.” This solution was preferred in comparison after studying other variants, in which “it became apparent that a complex that was less tall and with two or more buildings would affect the cityscape in a less acceptable and less beautiful way.” Construction ensued, and Roche Building 1 was inaugurated in September 2015 at a final cost of 550 million Swiss francs. Shortly before, Roche announced plans for a full campus redevelopment—Building 1 would be the starting point for the further development of the Roche headquarters, one of three main high-rises that will become the three tallest buildings in the country. These include the aforementioned Building 2, at 673 feet, and Building 3, at 433 feet. While Building 2’s realization is dependent on a 2016 vote by the Grand Council, there are currently no doubts that its construction will be approved.

The city’s recently appointed director of planning and construction, Beat Aeberhard, admits the Roche development “represents a scale jump for this city” but considers this to be “primarily a direct reflection of today’s society and economic prosperity,” pointing out how the Roche ensemble will produce a striking effect.9 While the new Roche campus will certainly be the most visible and drastic outcome of this “scale jump”—and have the least transparent process behind its erection—it is by no means the only one. Already in 2010, the city of Basel outlined a series of guidelines determining four larger and three smaller areas where the development of high-rises is planned and encouraged.10 Today, the design of many of these areas is under way, part of an urban-scale creation of four new centers for the city, linked to the historical core of Basel and in close proximity to it. Two of these are large-scale redevelopments of former industrial areas, one of which now features buildings by Morger Partner, BIG, and Herzog & de Meuron, to name a few.11 In the city center, new buildings for the university are under way, and others have just been announced, such as Caruso St. John’s new biomedical laboratory.12 The other two large high-rise developments are inextricably connected to both Roche and Novartis, with the latter having presented a scheme for its campus with three new towers rising up to 394 feet, to be completed by 2020.13

Together, these architectural visions promise substantial changes for the small city of Basel. Not only will this city in the next fifteen years gain a fundamentally new skyline, it will do so mostly at the expense of two of the world’s largest pharma companies. Roche, for example, wants to centralize its operations in Basel, bringing 9,000 more employees to work in its completed campus. Given Novartis’s expected growth, it’s easy to imagine an additional large increase in workers on the west side of the city (currently there are 10,000), in what would amount to a substantial increase in the city’s population. At the time of Building 1’s opening, Jacques Herzog stated how the building embodies his office’s answer to “the problems of uncontrolled development” in Basel and Switzerland. “In areas where there is already dense urban settlement, the aim should be continued, targeted densification.”14

For Basel, this seems to be the obvious way forward, even if a more conservative chunk of the population might not agree. Currently, several municipal education attempts are under way to inform the population about densification and high-rises, with initiatives and debates being launched in parks and neighborhood associations. Simultaneously, the Swiss Museum of Architecture regularly hosts panels and conferences about high-rises and the future of the Basel, with city representatives and architects present to reinforce the positive aspects of these changes.15 Even the official citywide tourism discourse lauds Basel’s new “landmarks.” On a recent touristic cruise up and down the Rhine, a previously recorded, English-speaking voice introduced tourists to the Roche tower, “a new landmark on the right bank of the Rhine.” Orchestrated or not, these joint initiatives seem keen on creating a similar discourse, reinforcing the idea that, in terms of architecture and urban planning, taller is indeed the best way forward. The overall feeling is one of trying to put a very stubborn and old relative in a nursing home, against their resolute objection.

The question that immediately follows from the densification debate concerns housing. This is a very pressing question indeed, particularly when considering the employees of the pharmaceutical companies and their general profile—expat, foreigner, no real need to integrate into Swiss city life and culture, and (given the international profile of their employers) no real need to even learn the local language, German. The most recent housing complexes built near the Novartis campus, such as Christ & Gantenbein’s Volta Mitte or Buchner Bründler’s Volta Zentrum (both completed in 2010), are beautiful, muscular architecture with stark geometric outlines but engage little with the neighborhood. To this day they remain gated communities for their international occupants. Should future housing built continue this trend, it would likely generate a divided city—one whose newly planned centers don’t engage with the Basel that exists today but instead create a new, independent city that is as much off-limits to the majority of Basel’s inhabitants as the pharmaceutical complexes that contributed to their making.

An editorial by Karen N. Gerig published in the local TagesWoche in October 2014, shortly after the final height of the Roche Building 1 became known, pointed out how the building makes evident Basel’s dependency on the pharmaceutical industry—and yet, “it would have been be very stupid and shortsighted not to allow this construction.” Rather dramatically, Gerig observes how “the height of the tower is also a sign of resignation. From the knowledge that there is no other way.”16 While such a bleak conclusion might express the general feeling of impotence around the existence of Roche Building 1, the realization that many more towers are to follow could help convert this feeling into a more active stance on the future of the city. Such an attitude could counter the effective no-public-access policy that currently surrounds the built and planned high-rises, allowing for future additions to the cityscape to become accessible to the general population, at least at the ground floor level.

In a recent interview Herzog & de Meuron expressed their own feeling of impotence, declaring that they “have no power” over what their clients ultimately want.17 Upon closer inspection, it seems their clients want nothing less than a building by Herzog & de Meuron. A map of the greater Basel area reveals twenty-nine built projects by the architects, who undeniably have a great hand in shaping the contemporary look of the city. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this influence can be traced back to the architects’ urban study, “A Nascent City?” (“Eine Stadt im Werden?”), that was commissioned by the Commercial Association of Basel and developed in 1991 and 1992. The study outlines an image of a future Basel where densification seems inevitable. It looks very similar to the city that is effectively taking shape today, where the Roche campus and Asklepios 8 are the first omens of a future that seems unavoidable, and which, for better or worse, will completely transform the city—and after it, the whole country.18

-

The building is named after Asclepios, a Greek god of healing and medicine. It is the first building on the campus to receive such a literary moniker—other campus additions are named after physicians or their location on the campus. ↩

-

“362 Novartis campus—Asklepios 8,” Herzog & de Meuron, link. ↩

-

See Herzog & de Meuron, Novartis Campus—Asklepios 8 (Basel: Christoph Merian Verlag, 2015). ↩

-

Buildings on the Roche grounds are named with simple numbers. The numbering of Building 1 denotes its importance in the renovation and expansion strategy of the campus. ↩

-

Emanuel Gisi, “Es gibt keine Besucher-Plattform,” Blick am Abend, October 23, 2014, link. ↩

-

For more on the exhibition, see the catalog S AM N° 13: Textbau. Schweizer Architektur zur Diskussion (Basel: Christoph Merian Verlag, 2014). ↩

-

These files were made public and can be downloaded from the website of the Basel City canton; see link. ↩

-

Yen Duong, “Es ist einfach nicht nötig, überall mit spektakulären Bauten zu operieren,” TagesWoche, August 6, 2015, link. ↩

-

The high-rise concept report for the Basel City canton can be accessed and downloaded from the Basel City canton’s website; see link or link. The report ultimately identifies areas of the city in which the construction of high-rises has been approved, and areas in which there is potential for the construction of high-rises. ↩

-

For project information, see, respectively, Morger Partner Architekten, link; “Transitlager by Big,” Dezeen, link; and Herzog & de Meuron, link. ↩

-

“Caruso St. John reveals designs for university laboratory in Basel,” Dezeen, November 5, 2015, link. ↩

-

The construction of these three towers is also dependent on an approval vote by the Basel City canton’s Grand Council. See “Novartis Campus erhält drittes Hochhaus,” BaslerZeitung, October 22, 2014, link. ↩

-

“18 Sep 2015—Opening Roche Building 1,” Herzog & de Meuron, September 18, 2015, link. ↩

-

The panels at the S AM usually gather a series of architects, city officials, and museum representatives, in mildly critical panels that don’t seem to offer alternatives to the high-rise densification the city is currently pursuing. ↩

-

See Karen N. Gerig, “Der Roche-Turm ist nötig, aber nicht schön,” TagesWoche, October 24, 2014, link. ↩

-

See Axel Simon, “Herzog & de Meuron im Gespräch,” Hochparterre, November 2015. The whole interview is a rich source of information on the architects' attitude towards the current transformation of Basel. ↩

-

The city of Zürich is undergoing a similar phase of expansion, as are many other locations in Switzerland. ↩

Vera Sacchetti is a Basel-based architecture and design critic. She is co-curator of TEOK Basel, managing editor at the Barragan Foundation, and co-founder of editorial consultancy Superscript.