Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 film Le Petit Soldat (The Little Soldier) gave us the famous assertion that “Photography is truth, and cinema is truth 24 times per second.” It sounds almost quaint in today’s Instagram-able world. But there remains a prevailing anxiety among film purists that the end of celluloid marks an end to cinema’s indexical relationship to reality. For a medium equally indebted to recording reality and fabricating fantasy, this is admittedly tricky territory. But to a degree, the concern is warranted. The photochemical film image represents a kind of factual stability, even if we know the camera is inherently editorial. After all, cinema’s origins are often located in the short actualités produced in the early twentieth century. Filmmakers pointed cameras at the world around them, recording quotidian street scenes and activities. These silent documents of daily life—naïve in the best sense—are among cinema’s first nonfiction films.

Of course, videotape was the first in a series of technological leaps that moved cinema away from its roots in still photography. The illusion of motion pictures was no longer tethered to the holy twenty-four frames per second. The digital revolution has initiated another rebirth of “cinema,” now as a seemingly immaterial medium of ones and zeros. The act of filming is now “capturing,” an arguably less sexy nomenclature, and the images produced have the advantage of being instantly and infinitely malleable. Every part of the frame can be modified, corrected, manipulated. This makes the digital image less stable, and therefore less “factual” in the eyes of some. Add to that a widespread embrace of “reality” as a genre and the application of verité, as one of many codified “looks” connoting authenticity. Even film grain is a filter applied as an effect in post-production. All of which raises the question of whether authenticity itself is a twentieth-century fabrication. Or perhaps it points to something we’ve always suspected—that all media is a matter of perception.

In a 2009 Artforum essay titled “The New Realness,” critic J. Hoberman argues that such anxieties are embedded in much of cinema today. Two recent examples come to mind. Godard’s Goodbye to Language (2014) is an optical assault experienced only in the theater that also functions as a farewell to cinema, while Disney’s nostalgia-fueled Star Wars reboot (2016) is a corporate blockbuster shot on 35-mm and handcrafted sets. Hoberman’s piece, however, opens with a quote by Film Forum’s longtime repertory programmer Bruce Goldstein, who astutely predicted in 1999 that all film would eventually become a form of animation. He was referring to the eventual domination of CGI. In many ways, this has proved to be correct, both for Hollywood and independent artists. Animation, as it happens, predates the development of cinema. A host of popular proto-cinema devices in the early nineteenth century, from flipbooks to Zoetropes, employed persistence of vision to animate still images. For some, the idea that cinema will be remembered as a subset in a larger history of animation is odd indeed. It suggests that digital technology loops us back to analog origins while also hurtling us forward into a disembodied future.

Why does any of this matter? For documentary filmmakers, “the real” still holds value. The impact of their work depends on a pact of trust between camera, subject, and audience. Yet technology and culture at large have thoroughly destabilized representation. Peter Bo Rappmund’s work, however, offers some clues as to what a twenty-first-century practice might look like. For one thing, it’s uniquely situated at the intersection of still and moving images. His technique, a form of stop-motion animation, harkens back to cinema’s origins while utilizing digital technology to transform raw data into documentary art. He produces films using a simple DSLR camera along with an intervalometer, a small device that allows him to take still photos at a regular frame rate. His process of filmmaking is therefore one of aggregation. For a typical project, Rappmund produces tens of thousands of photographs, which he then meticulously animates into hour-long feature films. The approach is something like plein air stop-motion, since he gathers all the material in situ. The process is distinct from time-lapse because Rappmund renders the subjects in something like real time. Five seconds of his film is more or less equal to the five seconds spent with his subject—or at least, that’s the illusion. The effect he achieves is uncanny, like looking at still photographs slowly coming alive.

Over the past five years, Rappmund has produced a remarkably coherent body of work documenting physical systems buried in plain sight in remote regions of the United States. His trilogy includes Psychohydrography (2009), Tectonics (2012), and Topophilia (2015), which premiered at MoMA’s Doc Fortnight. While they are “about” many things, these documentaries are most easily described as landscape films. Their visual drama derives from tensions between the man-made structures and the stunning natural environment. For each film, the process is the same: the filmmaker carefully traces a section of linear infrastructure at intervals across a large geographical expanse. Rappmund is a political filmmaker concerned with issues of power, social responsibility, and environmental awareness, but he is also an artist preoccupied with the nature of perception. These observational films are matter-of-fact in their presentation but also infused with a self-conscious subjectivity. They are, by design, meditative, open-ended affairs. Especially crucial is his eschewal of contextual detail. He offers no narration commentary, or on-screen text. Instead, he orients viewers through visual and sonic clues in the landscape. If the films have a message, it’s that we should trust our eyes and ears.

Rappmund’s films are, therefore, primarily sensory experiences. I like to think of them as off-road road movies composed of precisely crafted audio-visual field recordings. The filmmaker journeys to a far-off place most of us will never visit firsthand and returns with raw material that he carefully reshapes into a perceptual trip. You are invited to zone out. Psychohydrography traces the flow of water across nearly 300 miles from Eastern Sierra Nevada to the city of Los Angeles and ultimately the Pacific Ocean. As we travel from wilderness to metropolis, we closely follow a series of aqueducts and pipes situated above and below ground. Humans remain largely offscreen, even in the Los Angeles section. This absence, combined with an ominous ambient soundtrack, lend the film an otherworldly atmosphere of sci-fi. Tectonics follows a 2,000-mile stretch of the US–Mexico border, from the Gulf of Mexico all the way to Border State Park at San Diego–Tijuana. The notorious border wall appears and disappears and Rappmund often crisscrosses the border along the way. People remain largely out of view, but at times we hear voices speaking English and Spanish mixed on the soundtrack. One assumes this might be used as a device to identify what side we’re on. Language, we are reminded, never respects artificial borders, and here, it only serves to further blur the line.

Topophilia finds Rappmund again following a line to its logical conclusion. This time, it is the Trans-Alaskan Pipeline System (TAPS). Opened in 1977, this 800-mile pipeline—one of the world’s longest such structures—conveys crude oil from Prudhoe Bay at the state’s northernmost tip to refineries at Port Valdez in the south. The pipeline could not be buried in areas where permafrost occurred, which is almost everywhere, because the heat of the oil inside the pipe would have caused the structure to sink. The film, which took Rappmund four years to complete, is his most ambitious undertaking. In total, he produced more than 100,000 still photographs for the project. The film’s title—a provocation rather than a description—is taken from a 1974 book by geographer Yi-Fu Tuan. Rappmund explained that he first encountered the idea of topophilia (“love of place”) in Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space, where the concept is applied to interior and domestic space. But Rappmund was inspired by Tuan’s more expansive framework, which examines “place” within a larger network of social and environmental forces.

As with the water system in Psychohydrography, the pipeline in Topophilia functions for Rappmund as a literal and figurative manifestation of the (very) thin line separating the comforts of contemporary life from nature’s indifference. On a psychological level, the films may seem simultaneously motivated by fascination and fear. The filmmaker’s attitude toward his subject is compellingly ambiguous. Topophilia reveals TAPS to be both the essence of human folly and also a brilliant example of engineering prowess. Rappmund’s stunning photography underscores the dramatic visual contrast between the pipeline’s delicate linear form (it measures only 48 inches in diameter) and the vast, untouched, and unpopulated landscape. After watching it silently snake through the sublime Alaskan wilderness for hundreds of miles, it’s hard not to be impressed by the ingenuity and ambition of the structure. At one point, a series of insect-like lateral cables elegantly suspend the pipeline, allowing it to lift and traverse a river. For much of the film, it appears as an alien creature left to its own devices. Only briefly do we glimpse technicians; otherwise, the pipeline remains far from human contact. Because it is the only element in the landscape referencing the human scale, the viewer is brought into an unexpected identification with the object. Of course, I’m a New Yorker and tend to find unending wilderness scary; Alaskans would likely have a different reaction.

Central to all of Rappmund’s films is an on-the-ground perspective, which offers viewers an immediate and concrete spatial experience. This was not easy to pull off with a subject like TAPS. In a sense, Topophilia is a post-9/11 movie because security—or its absence—is the underlying subtext. The film was produced piecemeal during various trips to Alaska over a four-year span. Rappmund served as his own roving film crew, operating without permits and armed only with GPS. He followed the entire length of the pipeline alone, often sleeping in his rented SUV. (It’s an impressive commitment to self-reliance that feels prototypically American in character.) Security along TAPS is fairly lax. Rappmund told me that while there are surveillance cameras stationed at various points, enforcement is relatively nonexistent. The reality is that it’s nearly impossible to properly patrol an 800-mile pipeline through that territory, so Rappmund was able to get close to the structure undetected, especially in more remote sections. At the beginning, he had attempted to gain access to TAPS through the proper channels. Alyeska, the pipeline’s owner, offered to Rappmund that he photograph only the extraction points at Prudhoe and oil terminal at Valdez, and to do so from the safe distance of a helicopter. Access to the pipeline, he discovered, was denied to anyone outside the oil industry following the events of 9/11. As it happens, the majority of the land traversed by TAPS is privately owned. Aside from bears, the other real danger Rappmund faced while making the film was the prospect of gun-toting Alaskans who might not take a liking to his trespassing, a risk he took very seriously.

The perceptual realignment engendered by the film is the crucial result of the filmmaker’s slow and deliberate process. Shooting video certainly would have gotten Rappmund in and out of Alaska more quickly, but it would not have produced the hypnotic rhythms that define his work. For Rappmund, stop-motion is a way to defamiliarize the subject and to interrogate the act of looking. But on the level of process, it is a way for him to invert the received logic of digital technology, which is to make things happen faster and more efficiently. In Topophilia, he chose to use an analog cable release rather than a digital intervalometer. Controlling the frame rate by hand allowed him a greater degree of participation and introduced a subtle irregularity in the frame rate. It’s something that may register with viewers on a subliminal level. The post-production phase, in which Rappmund sequences blocks of still images into animated scenes, is the most labor-intensive part of the process. He constructs these sequences in a spatial manner, and likens it to the way a sculpture’s form will reveal itself gradually as a viewer moves around the object. In the filmmaker’s words, he “uses loops within sequences, and each iteration lets the viewer notice things he or she may have missed the first time, and the image becomes more stable in a sense.”

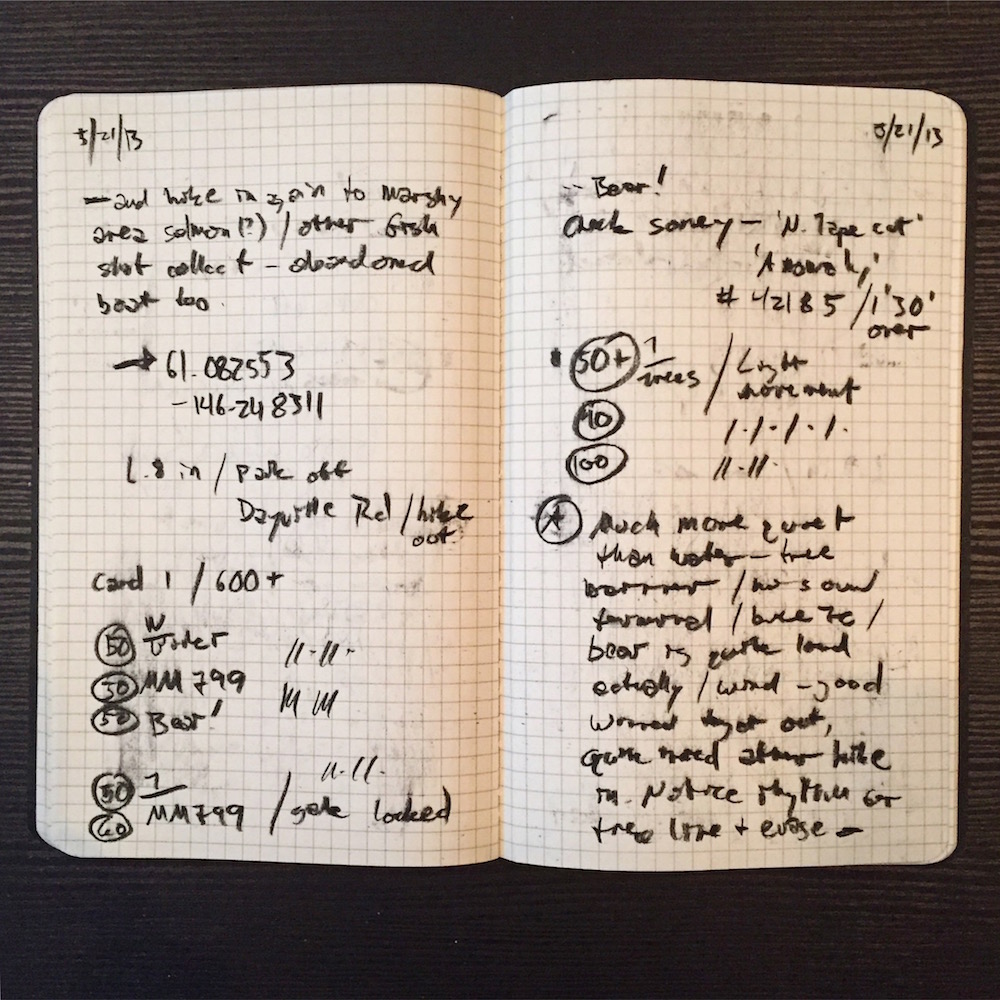

Rappmund’s formal and architectural approach to filmmaking bears traces of cinematic structuralism as well as the influence of avant-garde luminaries such as Stan Brakhage and James Benning, who were his teachers. In Topophilia, this is present in the use of bright orange mile-markers, which appear at regular intervals along TAPS. Operating like a countdown, these signs endow the film with a narrative structure and provide drama. We know that we’re headed toward something. But they also establish a crucial correspondence between actual and filmic time-space. They encourage our awareness of the slippages between the real and its representations when we traverse hundreds of miles in only a few minutes. However, this precise formal attitude is tempered by a more personal and instinctual approach, evident in Rappmund’s expressive treatment of sound and image. This lyricism can be linked to Brakhage. For each project, Rappmund maintains a handwritten journal in which he notes his own emotional state, as well as the day’s weather and light conditions, at a particular site. These notes help determine composition and become a key reference for tone and intention in the editing room. Rappmund, who has a background in music, also produced the film’s ambient soundtrack, which is composed of layered and remixed sound recordings he collected on-site. A recurrent pinging in Topophilia is actually the sound of the pipe’s metal expanding and contracting, which he captured by placing a mic directly on the structure. The soundtrack functions as an animating force, making still images vibrate with a sense of movement and wonder. At times, the soundtrack operates as counterpoint. While the images are animated to represent something close to real time, they are never entirely in sync with the soundtrack. In other words, each sequence in Rappmund’s film references multiple time signatures, which is another way he complicates a seemingly straight-ahead depiction of reality.

Rappmund’s process of accretion is closely linked to his political position and philosophy of artistic practice. His films offer a salve to the frenetic fatigue induced by the data-driven infographics dominating issue-oriented documentaries today. They reassert the value of duration and reflection in an age of instantaneous updates and reactionary responses. People might wonder what exactly to do with a film like Topophilia, since its stance remains resolutely non-didactic. It addresses today’s environmental crisis obliquely and offers no unnerving statistics or comforting prescriptive. It poses questions and leaves us without answers. It’s the kind of film that can frustrate activists, who will think it’s too pretty, and fans of narrative documentary, who will quibble with its use-value. Doesn’t a film about TAPS owe the audience more facts? I would argue that the facts of this film are to be found not in language but in sound and image. Prior to seeing Rappmund’s film, I had little awareness of TAPS. Like many people, I knew there was some kind of pipeline in Alaska, but it remained off my radar—which is how Alyeska would likely prefer it to be. Rappmund’s film succeeds on a pragmatic level, generating awareness of something that remains hidden in our landscape. It also serves a subversive purpose, as an illegal document exposing the very real physical conditions of the pipeline and our own vulnerability.

More important to me personally, is the transcendental dimension to Rappmund’s practice. Born of solitary journeys and a meditative process, the films are about connecting on a deep level with the American landscape. They are depictions of systems and processes and therefore circular in construction, even when they appear linear. Psychohydrography culminates in a voluptuous sunset over the Pacific, a visual tour-de-force. In the nearly ten-minute sequence, the stop-motion technique conspires with the rippling water and blazing light to produce a hallucinatory optical effect of looping, endless movement. We are reminded that the life of water continues. Topophilia actually begins in the nearby port of Los Angeles before traveling to Alaska. The location represents the next stage of the journey for the refined oil. But instead of a psychedelic sunset, the film culminates in darkness. After traveling 800 miles, we arrive at Valdez, and the film’s final image is a two-minute sequence of the flame burning atop a refinery stack. It is set against the black void of night, a flickering candle. The image feels sinister and unsettling but also weirdly comforting. An elemental image of fiery light captured on a digital sensor, and brought to life one frame at a time.

Paul Dallas studied architecture and works in film as a writer/producer, journalist, and programmer.