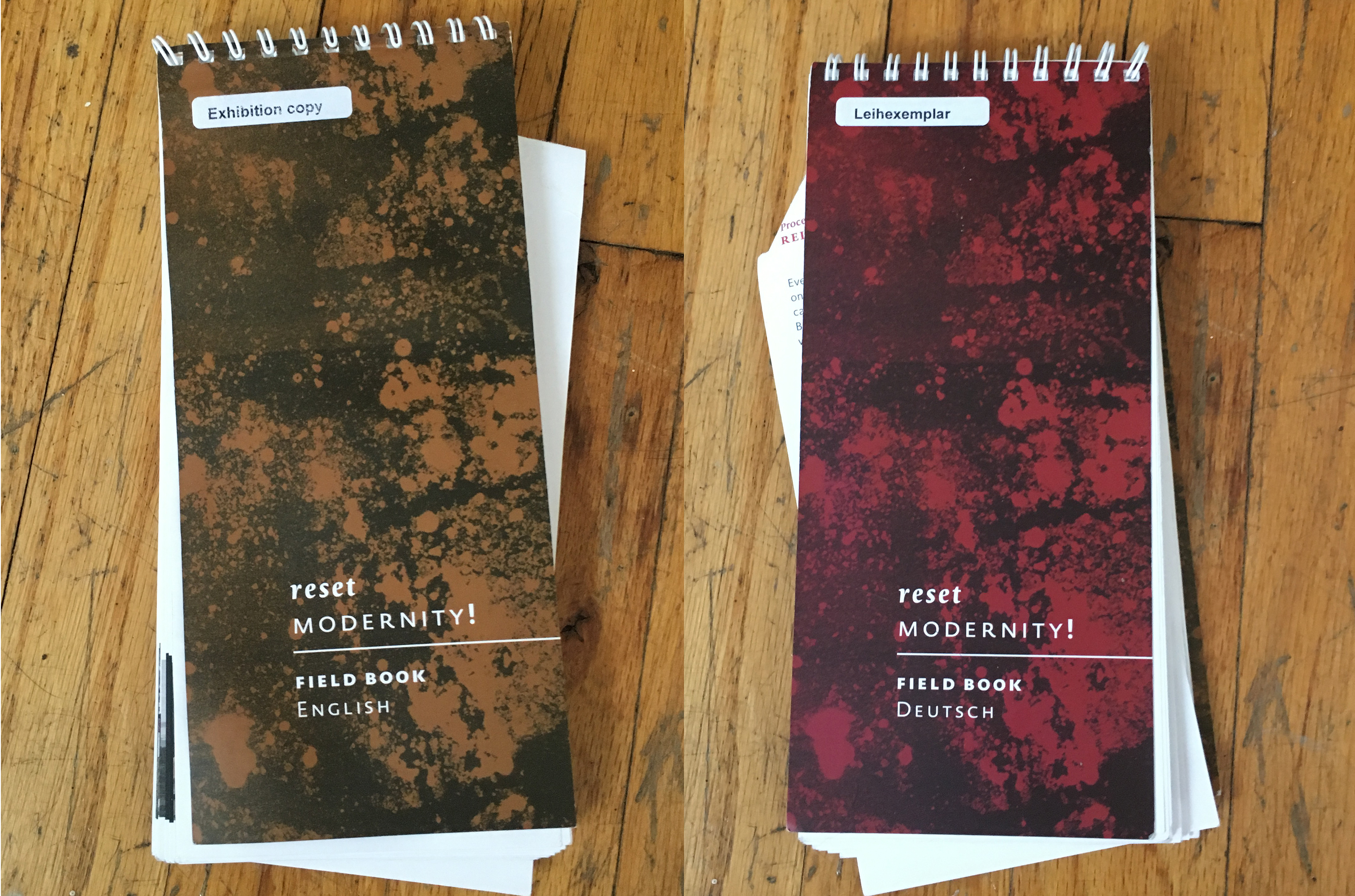

Walk in and pick up your field guide. This telluric-patterned flipbook, roughly the size of a steno pad or Brain Quest booklet (and perhaps functionally somewhere between the two), accompanies viewers through Reset Modernity!, the recent exhibition at the Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie (ZKM) curated by Bruno Latour, Martin Guinard-Terrin, Donato Ricci, and Christophe Leclercq.1 A “companion through the visit,” the booklet charts a path through the show’s six parts, called procedures, each reorienting that instrument we call modernity.2

The curators’ friendly discursiveness takes well to the field guide’s casual mode. Disarming and exuberant (a noticeable nine exclamation marks appear within it!), their observations and curatorial critiques offer a concise road map to an exhibition formed from decades of research across a range of media. Motivated by the same queries levied in We Have Never Been Modern, Latour’s anthropological treatise on the foundations of the scientific method and the rise of the secular, Reset Modernity! asks viewers to think of modernity like a compass gone haywire, and, through the medium of exhibition, consider new sensors and inputs that just might recalibrate our understanding of the modern.

In We Have Never Been Modern, Latour accounts for the emergence of modernity—alongside the impossibility of that modernity—in the social construction of the sciences. We believe, according to Latour, that the scientific method marks a schism in humankind’s understanding of itself, a shift from a worldview determined by faith to one dictated by rationality and politics where the human and nonhuman are inherently separated. The book argues that this isn’t true. Science was still formed as a matter of faith, and divisions between human and nonhuman, nature and technology, social and scientific are not so easily parsed. Reset Modernity! suggests that it is through a curious admixture of science and art that we may begin to see the modern anew. With the field guide’s reference to classification in mind, the exhibition doesn’t so much lay out a new terrain to navigate as provide a set of tools to encounter an already transformed reality beyond the gallery walls. It is an exhibition as “thought experiment,” in the words of the curators, with stakes both ideological and representational.3

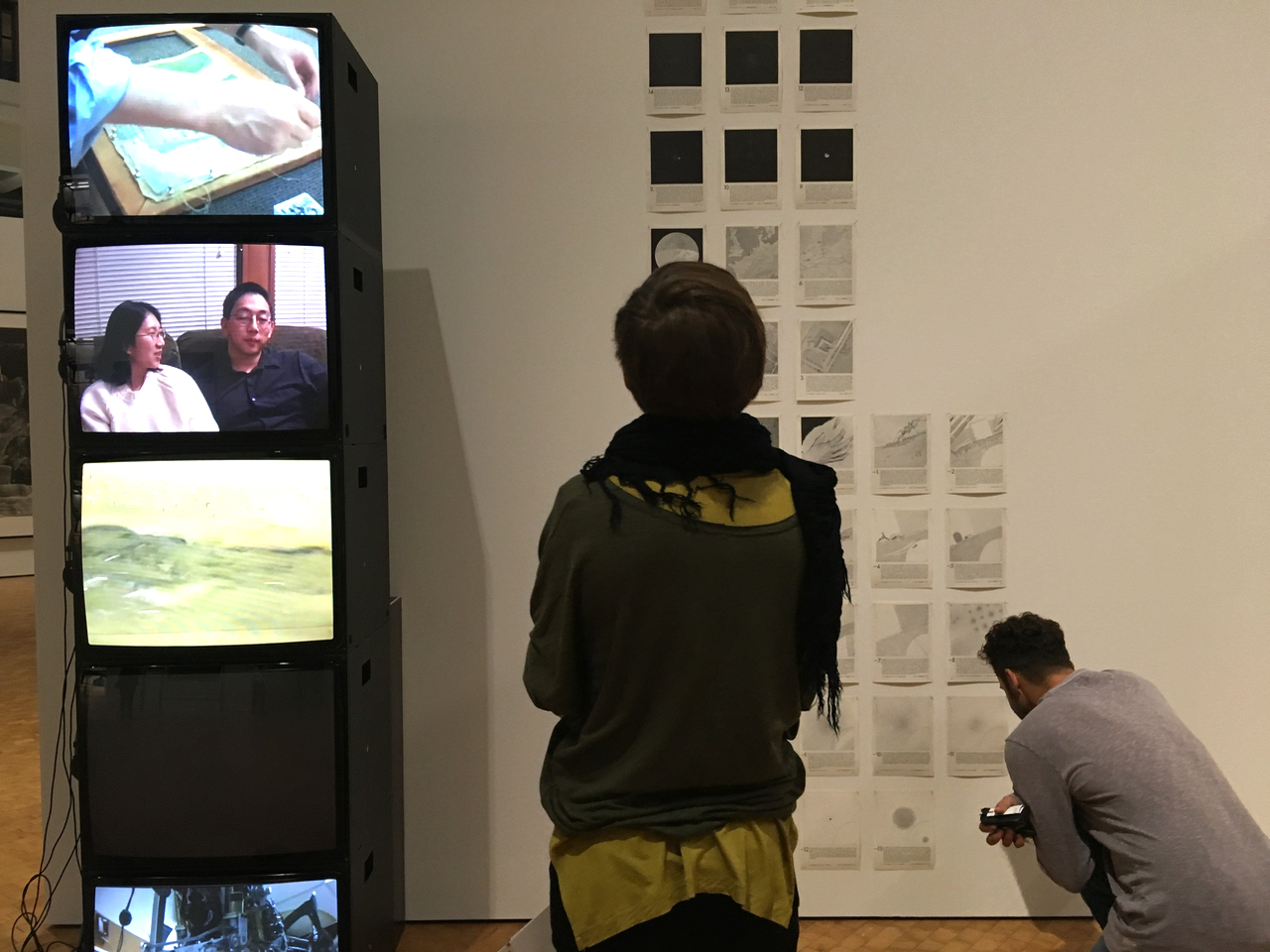

“Relocalizing the Global,” as the first procedure in Reset! is called (and yes, the booklet reads something like a sociology class syllabus), begins near a lakeside in Chicago with Charles and Ray Eames’s Powers of Ten projected on the gallery wall. “The film is very attractive … However we chose to show it here not only to enjoy it but also because something about this smooth cruise doesn’t work,” the guide suggests, prompting the viewer to turn instead to Superpowers of Ten, a recorded performance and installation by Andrés Jaque and the Office of Political Innovation. Superpowers is a gallivanting series of vignettes that, with a bevy of papier-mâché props and puppets, depicts the political injustices, alternative histories, and contingent narratives wrapped up in the making of Powers of Ten. These are scenes that would have never made it past the Eames’s neat splicing of cosmic order, a process displayed in the next piece, where the early sketches produced nine years before the film’s final release are played on television screens, bringing the act of editing to the fore.

Together these pieces make an argument about scale: a deceptively smooth transition from one vantage to another—the Google Earth voyage from outer space to the street that we are all familiar with—is a construct created through the very technologies that represent it; the global is never entirely visible. In representing the globe as totality, what we see is instead the fractured, fractious world just in front of us. It’s a thesis that readers of Latour will recognize and one that is rendered particularly well through the exhibited work. The Eames movie is displayed as both a process and historical artifact in dialogue with contemporary modes of architectural practice. In the same way, the curators engage a practitioner whose work addresses the very questions that vex their ongoing research. What’s on display here is not a static art object or a kind of archive of arguments past but rather an active form of dialogue through the work itself. The curators explained that the work was intentionally arranged as a linear argument, sequenced as a point and counterpoint, each piece in dialectical tension with that opposite, intended to be viewed as a progression of evidence supporting their thesis.

Consequently, spatial progression through the exhibition is also intended to be linear, following closely to the logic of the guide. In a show that aims to reframe modernity and question its epistemological effects, it’s disappointing that the exhibition as a medium is taken as given. Exhibitions are, after all, modern codifiers of knowledge, and to compose one so linearly is to fall into the very ordered understanding of the world the curators are attempting to destabilize. While many of the pieces on display question and subvert norms of representation—from the gaze of the viewer to the fixity of a finished work—the representational apparatus they are inserted into, which is to say the art museum with all its conventions, including linear, often teleological, spatial arrangement and circulation remains less challenged. There are, however, some beautiful slippages in our field guide’s ordered path. From the bird’s-eye view of the Powers sketches we are taken to the view from within the laboratory (another of Latour’s favored haunts) for Wall of Science, an installation of stacked television monitors playing short documentaries from the Harvard Cyclotron and Straus Center for Conservation Studies. They run from seven to fourteen minutes: narrations of canvas restoration; a fish swimming in a tank; and Tom and Jen, a couple explaining how their domestic life enters the lab where Tom works. It’s in the adjacency (not juxtaposition) of pieces like this with installations like Jaque’s, the commanding photography of Armin Linke located across the room, and the delicate tensions of Sarah Sze’s sculpture Model for a Weather Vane next to it that make Reset Modernity! such a beautiful discursive experience and compelling representational argument. Material exhibited isn’t confined to art objects or seen only as such; instead, through each piece the show’s artists and authors actively prod conventions in modern ways of seeing, infusing banal documents and fine art with relational meaning.

For example, archival “stations” in each of the six procedures mount documents, articles, sketches, and other material from An Inquiry into Modes of Existence (AIME), a collaborative research endeavor in the form of a publication and confoundingly labyrinthine online platform. These range from scans of Latour’s own writing to eighteenth-century engravings to the mind-warping perspective of Caspar David Friedrich’s Large Enclosure. Together these walls offer a kind of dossier-on-display, evidence of the ongoing project and a tracing of material informing the exhibited works. They also point to one of the show’s greatest challenges and ultimate strengths: how to use an exhibition to occasion research for a much broader project with many media formats. While Reset Modernity! is a continuation of AIME’s investigations and an outgrowth of their findings, it also stands on its own. Curators and exhibition designers could have emphasized this by treating the archival documents in the same manner as they did other work in the show within the context of critical adjacency instead of relegating them to a uniform presentation at a small size. Display at a larger scale would have animated the documents to a greater degree, encouraging them to be read with and against the other works instead of secluding and aestheticizing the archive as a singular object.

Latour is no stranger to the difficulties of displaying research outside of traditional academic channels. This is his third exhibition at the ZKM. Further afield, in 2015 he conceived of the play Gaia Global Circus, directed by Pierre Daubigny and performed at the Kitchen. AIME is a print volume published by Harvard University Press and an interactive website. If compasses are being recalibrated, they seem to be reorienting scholarly practice to incorporate a much wider array of representational modes. In a review of Gaia Global Circus, Rania Ghosn and El Hadi Jazairy comment that, “Beyond the accumulation of scientific knowledge, Gaïa embodies questions of representation, of what the issues are and where we stand vis-à-vis those issues.”4 Just as grappling with the gravity of Earth’s transformation demands recourse to the stage, its complexities may be best articulated through the affective qualities of visual representation. A vacant stadium in Warsaw after COP19; a whirlwind seen from the window of a plane; an indoor ski run in Tokyo; a dam in China; a laboratory in Italy; a trading floor in Paris. Armin Linke’s photographs are simultaneously elegant and unsettling, painstakingly composed shots of the mundane spaces where something we might call “climate change” is produced. The images appear in each of the procedures mounted near the floor or on slanted partitions dividing the gallery space. These subtle gestures of exhibition design invite an ever-so-slightly shifted gaze from the museum-goer as they look onto images of massive scale and sites so often evacuated of human form.

In We Have Never Been Modern, Latour writes of Thomas Hobbes and Robert Boyle, “They are inventing our modern world, a world in which the representation of things through the intermediary of the laboratory is forever dissociated from the representation of citizens through the intermediary of the social contract.”5 Linke’s photographs depict the inseparability between the two, bringing into focus the aesthetic resonances between the lab and the trading floor, between physical infrastructure and the spaces in which structural policy is determined. Those blurry spaces where the social contaminates the scientific—or vice versa—also animate the work of photographer Jeff Wall, whose images hang in the “Without the World or Within” section of the exhibition. In one, the artist Adrian Walker contemplates the human hand specimen he is sketching. In the other, an archaeologist writes notes at the side of a dig, watched by a member of the Stó:lō nation whose dwellings he is excavating. Both of these photographs subvert the typical gaze of Western art history and of science, one by confusing the distinction between science and art, the other by placing the archaeologist in the role of the observed. They do so with the careful choreography characteristic of Wall, lending an arresting sense of slight uncanniness to the tableau.

The box of the archive, the Xerox machine, the coffeepot. It’s in the institution’s banal materiality that the structural effects of modernity are produced, explains Latour in Reassembling the Social. “Even Karl Marx in the British Library needs a desk to assemble the formidable forces of capitalism,” we are reminded.6 Reset Modernity! uses photography and film to evoke these sites with intensity. Leviathan, a “sensory ethnography,” as filmmakers Véréna Paravel and Lucian Castaing-Taylor call their video installation, is projected on a screen in a large black room—the only film to be shown in a screening room. Leviathan documents the movement of a fishing boat in the northern Atlantic. Cameras affixed to the boat present multiple vantage points into and out of a ship at sea: a close-up of a cormorant flapping on deck, struggling in surging waves; a fisherman slicing skate fins and tossing them into the water; a motor lifting a net. Instead of a single subjective point of view, we see the interaction of human, nonhuman, and machine. Eschewing cinematic convention, the camera itself is a material participant in this event; its unprotected lens is treated less as an invisible technology and more as a surface to intensely register the experience of these different subjects, its frame at times obstructed, unfocused and dirty as it’s splashed with fish blood and ocean water.

As the show comes to a close, we’re again standing in front of a screen watching a projection. On it President Obama delivers a eulogy for victims of the Charleston church shooting. The piece is Obama’s Grace, by Lorenza Mondada, Nicolle Bussien, Sara Keel, Hanna Svensson, and Nynke van Schepen, a group of sociologists and linguists working in collaboration. In it they render the patterns of Obama’s speech and the responses they solicit in the audience. By screening speech analysis diagrams alongside footage of the eulogy itself, they reveal the rhetorical intersections between the religious and the political and their inherent entanglement. “The aim of this analysis,” they write, “is to demonstrate some systematic practices transforming a discourse about grace into a collective state of grace.”7 This process was one created for the commissioned piece, created by bringing social science into the gallery setting.

An exhibition–as–thought experiment runs the risk of being curatorially heavy-handed, sublimating authorship with argument and only mobilizing work as evidence of a claim formed before the show was conceived. The format also has the potential to approach the exhibition format as a venue to test ideas and engage with others testing the same ideas in different fields and different media, transforming the gallery into a space of interdisciplinarity for more than interdisciplinarity’s sake and destabilizing the notion of the “art object.” Some critiques levied at the show have suggested that Latour simply instrumentalized art and artists, undercutting their own authorship and meaning with didactic explanation to serve a linear argument. Reset Modernity! assembles a staggering collection of work from architects, filmmakers, sociologists, anthropologists, photographers, and painters. If the curators had not pulled together such robust and heterogeneous a show, then yes, it’s possible the work could have been subsumed by the curatorial hand. But here it stands on equal footing, in dialogue with each curatorial provocation as well as much, much more. The audience is, after all, free to dispense with the handy flipbook and wander the gallery on its own terms. Partitions interrupt a smooth and linear flow of foot traffic at unexpected angles, fragmenting the gallery floor and hinting that there are multiple paths through this field.

Regardless, at 6:00 p.m., you must put your field guide back. As our tour with the curator nears its end, the museum guard intervenes. The ZKM closes as six o’clock sharp, and no amount of persuading will convince him otherwise. Sometimes you just can’t escape institutional constraints.

-

For more information on the telluric lithography process for both the cover art of the field guide and exhibition catalog, see Reset Modernity!, ed. Bruno Latour and Christophe Leclercq (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), 42. ↩

-

Bruno Latour, Reset Modernity! Field Book (Karlsruhe, Germany: ZKM Publications, 2016). The procedures: Relocalizing the Global, Without the World or Within, Sharing Responsibility: A Farewell to the Sublime, From Lands to Disputed Territories, Secular at Last!, Innovation Not Hype. ↩

-

Latour, Reset Modernity! Field Book. ↩

-

Rania Ghosn and El Hadi Jazairy, “Gaia Global Circus: A Climate Tragicomedy,” Climates: Architecture and the Planetary Imaginary (New York and Zurich: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City and Lars Müller Publishers, 2016), 54. ↩

-

Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern, trans. Catherine Porter (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993), 27. ↩

-

Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 175. ↩

-

Latour and Leclercq, Reset Modernity!, 396. ↩

Caitlin Blanchfield is PhD candidate at Columbia University's Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, and a contributing editor to the Avery Review.