In affordable housing circles, architects increasingly promote “outcomes-based” or “impact” design, frameworks that judge architecture by its social, economic, environmental, and health impacts. While writing this article, I was invited to one such convening, discussing “how quality housing design can help achieve affordability while enhancing the public realm; supporting long-term sustainability; responding to the culturally diverse nature of New York neighborhoods; and positively impacting citizens’ health, safety, and well-being.”1 Housing for people with low incomes is expected to meet wide-ranging high-performance standards, in part to justify public and philanthropic subsidies. In contrast to social-justice- and funding-minded conversations around below-market housing, press surrounding Via 57 West, the new luxury housing development by Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) in New York’s Hell’s Kitchen—like many reviews of high-end architecture—has focused on the building’s form and finishes, characterizing Via as a “modern icon … with Cesarstone countertops.”2

What if we judged luxury projects like Via 57 West by the demanding criteria placed on below-market housing? BIG founder Bjarke Ingels has espoused a certain kind of outcomes-based design himself: “All of Hell’s Kitchen is the way it is. The whole world is the way it is. And we [as architects] do this one thing different. And what are the consequences for everything around us?”3

What are the “consequences” of Via 57 West? What are its impacts? If Via were a below-market building, my fellow “housers” would ask, “Was the community engaged?” “Does the building produce better health outcomes?” “Are there on-site social services?” “Is it cheap enough?” And—most important: “Is it replicable?” Indeed, those are the questions asked of Via Verde, another recent courtyard housing development, but one for low- and middle-income residents.4 Via Verde, a 222-unit below-market development in the South Bronx, resulted from New Housing New York, the city’s first competition for “affordable, sustainable housing.” The development cost $474,000 per unit in 2016 dollars, compared to $656,000 for Via 57 West, yet the former—a well-designed, well-managed, energy-efficient, award-winning project, whose production was grounded in community engagement—is dismissed by many critics as too expensive and therefore unreplicable.

Is Via 57 West replicable? No—and who cares? But we should demand as least as much from luxury housing as we do from buildings for poorer residents, not only because these developments also benefit from public subsidy but because all housing should enhance its neighborhoods and enable its residents to lead healthy, productive lives.

Community within the building OR are there on-site social services?

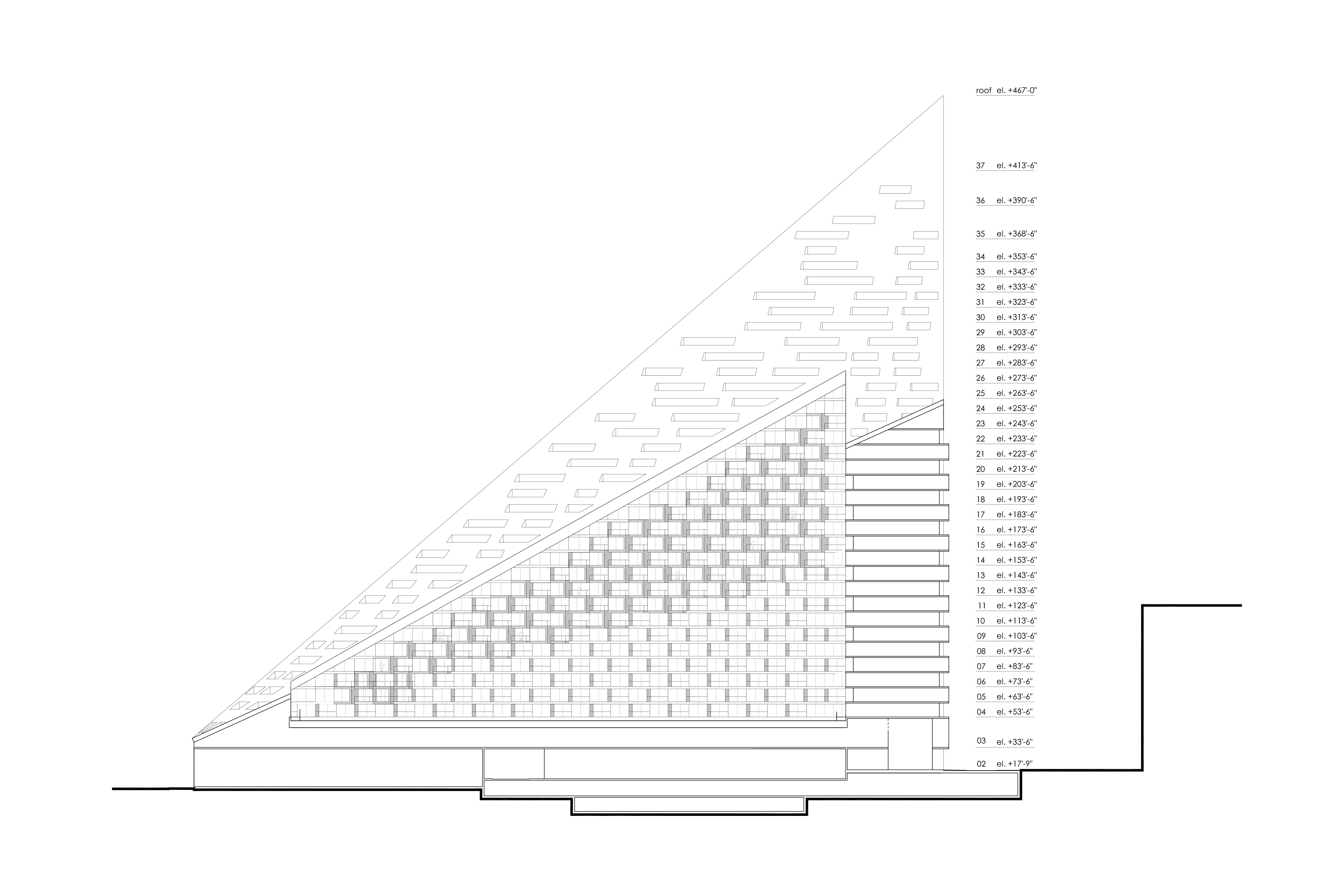

If you have seen Via 57 West in person, it was likely from the West Side Highway or maybe New Jersey. When I first saw the building, from the window of a taxicab, I did a double-take. Just one story tall at the highway, Via pulls up to form an asymmetrical, thirty-two-story tower at the northeast corner of the site. Its matte stainless-steel unitized façade describes a ruled surface, rising from just above street level to 467 feet.5 A giant rectangular cut through the middle of the building produces a courtyard lined with saw-tooth balconies angled toward the Hudson River. There are other curvy structures along the West Side Highway—Frank Gehry’s IAC Building being among the more dramatic—but where those operate within a typical New York City step-back zoning envelope, Via defies it. Immediately, I wondered how such a dramatic structure could have been built in New York, a city whose building regulations and real estate demands often produce cookie-cutter towers.

Ingels calls Via a “man-made mountainside,” a form that may be BIG’s specialty. The firm has also designed the sloped Amager Bakke facility and aptly named VM Mountain Dwellings in Copenhagen as well as the hill-like Hualien residences in Taiwan. Via was BIG’s first New York commission and has become the firm’s biggest and most expensive built project. When it won the commission, the Copenhagen-based firm set up a tiny office in New York and “camped out” at the City Planning Urban Design Office, where staffers helped them get up to speed on New York City zoning regulations.

The 709-apartment, pyramid-like Via, developed by The Durst Organization, is envisioned as a “gateway” to New York. From afar Via appears less like a building than a sculpture or an icon. Indeed, its symbolic status was integral to its creation. In approving the building’s development, the New York City Planning Commission wrote, “The building’s massing and architecture will add a prominent visual marker to Manhattan’s western skyline.”6 Beyond its striking form, the building represents New York City’s attempt to enliven a formerly industrial waterfront site, bring cutting-edge architecture to New York, and provide affordable housing through incentivized private development, all hallmarks of Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration (2002–2013).

Beyond its iconic form, Via is designed so residents never have to leave. Organized around a twenty-two-thousand-square-foot private courtyard, the building arrays a series of programmed common spaces along its south and west sides: occupants can work in the reading room or one of the lounges; work out in the gym, the fitness lounge, the swimming pool, the exercise studios, or the indoor half-basketball court; meet their Via neighbors in the movie screening room, the party room, the poker room, the chef’s kitchen, or the golf simulator and putting green or the ping-pong, billiards, and shuffle-board game room; bring their kids to the “tot spot” playroom; and relax on one of the sun decks, in an outdoor lounge, or at a poolside yoga class.78 One lounge is nicknamed “The Yacht Club.” Ground-floor commercial tenants—Landmark Theaters, the Ousia Mediterranean restaurant, and the American Kennel Club—are set to move into Via soon, along with the “farm-to-table organic” Hudson Market at the base of the neighboring Helena, opening spring 2017.9

Facilities like these might seem lavish, but they have their origins in working-class housing. New York cooperative housing developments, built mainly from the 1920s to 1970s, typically contained a range of collective social spaces, including theaters, libraries, meeting rooms, restaurants, and health clinics. As David Madden and Peter Marcuse point out in the recently released In Defense of Housing, “Elements of radical housing experiments persist today, but often in privatized and commodified form.”10 Housing for low-income people increasingly incorporates amenities like health clinics and rooftop gardens—as in Via Verde—as attempts to improve the health of its residents, who are disproportionally affected by preventable chronic disease. Supportive housing, usually reserved for residents who are formerly homeless or mentally ill, typically contains on-site social and health services. Statistically, people who can afford Via 57 West market rents are likely to be healthier but, like anyone, can benefit from having health, leisure, and work spaces close at hand, particularly to balance the building’s relatively small apartments. Since the mental and physical benefits of open space are well documented, “outcomes-based” designers would especially applaud Via’s courtyard.

Via’s ambitious suite of amenities also reflects the lack of street life in the neighborhood. On the eleven-minute walk from Columbus Circle, down Fifty-Seventh Street, you leave the familiar fabric of New York behind and pass half-block-long CBS and BMW complexes before arriving at the site, which had for years been a vacant, windy no-man’s land. That far west, Durst vice president of public affairs Jordan Barowitz told me, “You need to have a real community within the building.”11 The cloistered structure responds to a hostile site. Ingels calls the courtyard scheme “an oasis.”12 Via is directly east of the West Side Highway, adjacent to Hudson River Park Piers 97 to 99, which host a planned public park, Con Edison parking, and a Department of Sanitation Marine Transfer Station. Though the site itself is no longer zoned for manufacturing, the neighborhood retains pieces of its grittier past.

Via is the largest of three Durst developments that together occupy a full block. Durst controls the site—between Fifty-Seventh and Fifty-Eighth Streets, and Eleventh and Twelfth Avenues—under a ninety-nine-year, 1999 land lease agreement made with the block’s private owner. The rental apartment buildings, each with ground-floor retail, are aimed at residents with a range of middle and high incomes: The ten-story, sixty-five-unit Frank, at Eleventh and Fifty-Eighth, by Studio V Architecture, which will soon open as a non-doorman building, will have the lowest rents of the three properties. The Helena, a thirty-eight-story, 597-unit tower built in 2005 at Eleventh and Fifty-Seventh and designed by FX Fowle, has fewer amenities than Via and is medium-priced by Manhattan standards. With prized views, a waterfront site, high design, and amenities, Durst calls the luxury Via the trio’s “gold standard.”

Though the three properties appear distinct, they are physically integrated through a shared black-water recycling system. A natural-gas shuttle for residents also serves all buildings, looping between the site and Columbus Circle during rush hour. The shuttle that brings tenants together also separates them from the neighborhood, however, meaning that the economic benefits of the new Hell’s Kitchen residents may be contained on site. There were no community charrettes for Via 57 West, as there would likely be for a low-income development, though the site’s rezoning did trigger a public review. In lieu of local input, Via’s architect, developer, and consultants used their understanding of market desires to produce the building’s form, which was tempered by government design and development requirements, intended to serve the public interest.

An off-center, slightly twisted pyramid OR is it replicable?

In place of Via, Durst almost built a pair of giant parking structures. Mayor Rudolph Giuliani’s administration approved the developer’s 2001 application to erect two public parking garages on the vacant site, for a total of almost seven hundred spaces. The Giuliani administration was also responsible for a 2001 large-scale rezoning of the surrounding neighborhood and a portion of the Durst site, from manufacturing (M1-5) to commercial (C4-7), a designation that also allows housing to be built. This was part of a decades-long series of rezonings of formerly industrial New York waterfront neighborhoods to accommodate primarily residential development, including Far West Midtown with Hudson Yards, south of the site.13 Subsequent city-approved development plans for the Durst site, under Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration, in 2004 and 2008, would have allowed an office tower or a school.

In 2012, Durst applied for a special permit to rezone the block from a mix of commercial (C4-7) and manufacturing (M1-5) to fully commercial (C4-7 and C6-8)—equivalent to dense residential zoning (R10 and R8). In its unorthodox developer-initiated application to the New York City Planning Commission, then chaired by Amanda Burden, Durst also asked the City to redistribute the site’s allowable floor area, permit almost three hundred enclosed parking spaces, and waive setback and other formal zoning requirements. Manhattan Community Board 4 (CB4), whose district includes the site, recommended that the commission deny Durst’s applications unless “20 percent of the units developed be affordable in perpetuity.”14

In its ultimate approval of the application, the commission did not meet CB4’s demand for permanently low rents. Instead, the below-market apartments will remain under current rent regulations for thirty-five years, at which point, upon vacancy, they will enter the New York state rent-stabilization program. Since below-market apartments have a low turnover rate, Barowitz estimates the units will continue to have low rents for about fifty years. Rejecting CB4’s call for permanent affordability, the City Planning Commission wrote, “Voluntary, incentive based programs are appropriate tools to encourage the production of affordable housing in conjunction with new development. Mandating … that any affordable housing provided under the ‘80/20’ program be made affordable beyond the terms of the affordable housing financing agreement, would be contrary to this established policy.”15 And so the premium housing will be accessible to low-income New Yorkers but only for a limited time.

The Commission did require Durst to modify the development to create a more inviting streetscape. Mandatory design modifications included expanding the pedestrian portions of the midblock access drive to specific widths and adding “trees, planting beds, and benches that would flank the driveway and signal the transition between vehicular and pedestrian space” and providing transparent façades at the ground floor.16 Via could not have been built under standard New York City zoning, which would have produced a more traditional building with typical street walls and setbacks. By waiving some formal requirements, the City allowed the construction of a building whose “ultimate form”—as described in the official City document – “reflects the shape of an off-center, slightly twisted pyramid.”

Via’s striking design was integral to the zoning deal. In effect, Amanda Burden demanded it. Before BIG was brought on board, Burden rejected Durst’s high-rise proposals for the site by other architects. The City liked BIG’s first design proposal—a fifteen-story building—but the scheme would have required two lobbies and attendant staff, making it expensive to operate. On Durst’s request, BIG went back to the drawing board, to design a building with only one lobby that would preserve the Helena’s Hudson views—meaning that the mass of the building would have to be shifted to the northeast. Burden liked what she saw. After more than a decade of false starts, Durst finally had its development scheme. Though just opened, Via is a time capsule from 2012, a moment when New York City government favored high design more and affordable housing less than it does today and when rezonings had opened up large-scale waterfront sites for lucrative residential development.

Durst chairman Douglas Durst and BIG founder and creative partner Bjarke Ingels met in 2006 in Copenhagen at Durst’s green-building lecture, where Ingels asked, “Why do all your buildings look like buildings?”17 At the time, the then-32-year-old Ingels was already becoming known for his formally experimental architecture, with BIG, and before that, with PLOT, the firm he ran with former Rem Koolhaas Office for Metropolitan Architecture coworker Julien de Smedt. Selecting BIG for the Via job in 2010, Durst had Burden’s approval in mind. Durst vice president Barowitz told me in an interview, “Amanda Burden wanted a building of architectural significance. We knew BIG would design something that hadn’t been seen before.”18 Later, Burden’s City Planning Commission argued that Via’s unique design helped warrant the City’s rezoning approvals: “The Commission believes that approval of these actions would facilitate the development of a significant mixed use project with a distinctive design and thoughtful site plan.” According to Barowitz, the building’s design has also helped it lease up—residents “want to be a part of it.”

In a 2015 interview with New York Times chief architecture critic Michael Kimmelman, Ingels spoke against the typical housing design process, which he characterized as “taking a bunch of boxes,” or apartments, and stacking them in an efficient way. BIG took the opposite approach, designing the building from the outside in.19 Barowitz calls the resulting form “practical”—since shifting Via’s mass toward the northeast preserved the Helena’s Hudson views and let light into the Via courtyard while maintaining just one lobby. Ingels argued similarly for the practicality of the design: “We turn a rational and rigorous analysis of the performance of the building into the driving force for the architecture,” but the firm’s focus on the overall building form, over the apartments within, did a disservice to the living spaces. BIG presents its “rational” design process by cherry-picking only certain performance constraints, denying the obvious, that an expressive formal gesture was the firm’s primary goal. Another design for the building—perhaps without a hyperbolic paraboloid—could have met requirements for light, views, and a single lobby while achieving more satisfying internal spaces.

To fit the apartments into the building, SLCE Architects, the architect of record, had to produce 178 unique apartment designs, some of them with awkward floor plans and long internal hallways. When asked about the efficiency of so many unit types, Barowitz told me, “We knew what we were getting into. We thought we could build something special.” The building’s layout also produces long, double-loaded corridors with no natural light. Angled apartment entryways give some sense of public-private thresholds, but the corridors, some as long as five hundred feet, are impersonal and monotonous, something that could have been avoided by paying more attention to internal logics.

The apartments themselves fail to take advantage of the building’s expressive section—standing in one, even at the top floor, gives no sense of the theatrically angled roof façade above. Instead, residents will look up at standard flat ceilings. The light-filled spaces have stunning views through floor-to-ceiling windows and refined finishes in a muted palette, selected by BIG, under partner and project manager Beat Schenk, but are otherwise ungenerous and without character. The building’s overall form does create successful spaces in the balconies, however. Where balconies intersect with the steep façade, calibrated openings produce semi-enclosed spaces that shield from the wind while maintaining Hudson views. They feel at once protected and part of the city.

Down at street level, residents enter Via by way of a midblock drive connecting Fifty-Seventh and Fifty-Eighth Streets, which also provides access to parking at the Helena. The drive feels public, even though it is private—a successful result, in part, of the City Planning Commissions’ required, pedestrian-oriented design modifications. In our interview, Barowitz called the City rezoning process and related design changes “helpful.” Other City requirements, for multiple entrances at the ground-level commercial spaces and vitrines along Fifty-Eighth Street help to break up the large building mass and enliven an otherwise unpopulated site. Thanks to the City’s detailed design interventions, Via contributes to a more livable streetscape, though a better connection to Hudson River Park is still needed.

Douglas Durst, a third-generation leader of the family real estate company and a graduate of Berkeley in the sixties, insisted on using sustainable materials throughout Via. According to BIG and Starr, Durst was hypervigilant on environmental issues, demanding full specifications on potential building products and rejecting off-gassing and other unsustainable or unhealthy materials. Barowitz told me Durst wanted “a home that is a healthy place to live.” Because Via is a rental building, Durst directed BIG to use materials that were inexpensive but durable. After Superstorm Sandy, mechanical systems were elevated in a flood protection strategy.

Durst is now working on another, larger waterfront in Astoria, Queens. Designed by Dattner Architects and others, the 2.4-million-square-foot mixed-use Halletts Point is set to open in 2018. What can the new project tell us about Via’s replicability? Like Via, Halletts Point also involved a rezoning and will contain 20 percent below-market apartments, but the Astoria buildings will definitely look like buildings. Though certain financing mechanisms and sustainable building systems were repeated, the project’s design looks nothing like Via, nor should it, since the site and program are unique. More important than traditional conceptions of replicable architecture—which in below-market housing can be a code-phrase for “cheap”—are regulatory mechanisms that operate in the public interest while allowing architects to respond to the constraints of a specific program and site. The absurdity of judging a project like Via by its direct replicability should call into question the standard for buildings of all budgets.

$4,450 or $725 for a one-bedroom OR is it cheap enough?

The construction of Via was made possible by government tax incentives and financed with tax-free government bonds. By renting 20 percent of Via’s apartments at prices set for low-income residents, Durst qualified for New York City Inclusionary Housing tax incentives. As required by the public financing program, the $465 million development contains 142 below-market—“affordable”—apartments, reserved for people making 40 to 50 percent of the New York City region Average Median Income (AMI), currently $72,500 for a “family of two.”20 Rents for these units are set at 30 percent of a household’s income, meaning that a couple making 40 percent AMI ($29,000) would pay $725 per month for a one-bedroom, and a couple making 50 percent AMI ($36,250) would pay $906. The average market-rate rent for a Via one-bedroom is five to six times those figures, at $4,450—“affordable” for a two-person household making $178,000 a year, or about 250 percent AMI. The below-market apartments are distributed evenly throughout the luxury building, except above the twentieth floor, where all units are market rate. Though not required under government and funding-based regulations, Via was built using union labor.

As is typical for developers of luxury buildings incorporating 20 percent below-market units, Durst was also given a ten-year tax exemption under the 421-a program—a New York State tax incentive for multi-unit residential development on vacant land. In terms of the building’s economic impacts, this means that New Yorkers will not benefit from Via property taxes for a decade. When this project was conceived, private construction loans for a project of this size were both difficult to find and expensive, meaning that public financing, even with its affordability requirements, provided the most economical way for Durst to get the project built.

A garden on structure OR does the building serve its community?

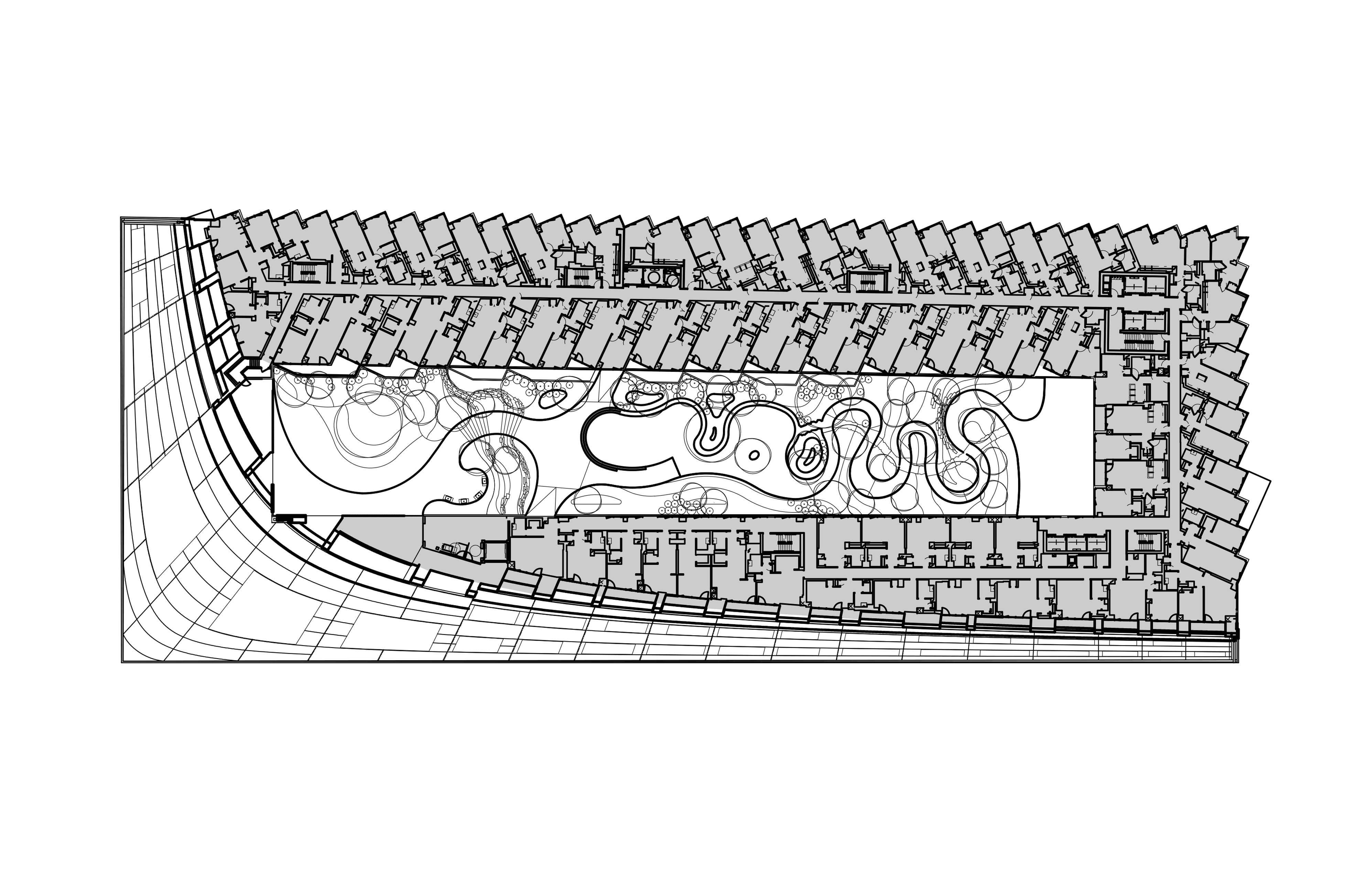

Via’s courtyard has the feel of a utopian space where residents would form community. Touring the garden, I imagined a resident spying a barbecue party from her balcony and coming down to join or a child calling up from the courtyard to a friend to gather enough players for a game. When Ingels calls the Via courtyard a “bonsai Central Park”—at the same proportions, if thirteen thousand times smaller—it is more than a marketing ploy. Starr Whitehouse partner and Via landscape architect Laura Starr is a former Central Park Conservancy chief of design. She told me that producing natural-feeling, manmade landscapes is “hard enough to do in Central Park. Here, the challenge was making a garden on structure.” Importing a Central Park design philosophy, Starr used forty-seven species of native plants to make the courtyard feel like it was “transported from nature.” The design disguises the fact that the garden sits above the building’s 285-space parking garage, overcoming technical challenges, including complex drainage issues.

The inclined courtyard garden rises from east to west, with level gathering areas at three different elevations, connected by a sloped, winding brick path resembling a mini Lombard Street. Entering the courtyard from the building lobby, via the grand staircase and through glass doors, a small sitting area gives way to a birch and fern garden, followed by an organically shaped gathering space with a long, snaking bench and less dense landscaping, and then up to the sunniest part of the garden, a lawn and Hudson River overlook.

In the courtyard, Durst’s insistence on green materials had the beneficial side effect of eliminating traditional playground materials, which were nixed because of their off-gassing properties. Instead, the landscape integrates rocky climbing areas and unprogrammed open spaces, making for more adventurous, free-form play zones. Starr noted in our phone interview, “We always try to imagine all the people—the 80-year-old, the four-year-old, the sexy people, introverted and social, trying to meet each other.” 21 A stepped, rocky path is intertwined with the ADA-compliant winding ramp, interlinking spaces for the youngest and oldest inhabitants.

New York courtyards may be making a comeback, due in part to rezonings that have made large sites available for residential development. Like Via, new projects such as Lambert Houses in the Bronx and the Oosten condos in Williamsburg are designed around large courtyards, inspired by European perimeter block schemes. Sagi Golan, senior urban designer at the New York City Department of City Planning Brooklyn Office, is researching the dozens of existing New York courtyard buildings to help think about the future of the typology. Early New York courtyard buildings, like The Apthorp (1908) and The Dakota (1900) on the Upper West Side, are some of the most celebrated residential developments in the city’s history. These courtyards, though, unlike Via, are at grade, with visual access to the street. New introverted courtyard schemes, as earlier examples, meet the challenge of providing usable open space within dense development, bringing in light and air and giving residents a respite from the city.

Via’s courtyard might be a place for all residents to come together, but the garden is part of a membership-based amenity package. With an annual fee of $1,000 (currently $500 for the first year), the courtyard and other communal spaces may be out of reach for lower-income tenants. As Madden and Marcuse write in In Defense of Housing, “The built form of housing has always been seen as a tangible, visual reflection of the organization of society. It reveals the existing class structure and power relationships.”22 At Via, the even distribution of below-market apartments throughout the building and shared entrance for rich and poor tenants, as required by law, give the appearance of an egalitarian space. But the expensive amenity package effectively establishes classes of occupation within the building, keeping poorer residents out of Via’s semi-public realm. An overarching goal of impact design is to use architecture to help produce more equitable environments to counteract our cities’ existing economic, social, environmental, and health disparities. If low-budget housing for low-income people is expected to make positive impacts on all of its residents and its neighborhoods, truly iconic luxury housing should do the same.

-

Fine Arts Federation of New York 2016 Annual Meeting, “Designing Quality Affordable Housing,” November 1, 2016, New York Foundation for the Arts, 20 Jay Street, Brooklyn, link. ↩

-

Pei-Ru Keh, “New (Residential) Icon: Introducing Bjarke Ingels Group’s Via 57 West,” Wallpaper, February 26, 2016, link. ↩

-

Mark Binelli, “Meet Architect Bjarke Ingels, the Man Building the Future,” Rolling Stone, September 14, 2016, link. ↩

-

For my own review of Via Verde, see “Via Verde,” Domus, June 14, 2012, link. ↩

-

Via’s sloped façade was fabricated and assembled in Richmond, Virginia, by Enclos—the façade fabricator that provided design-build services for all Via façades—in collaboration with façade consultant Israel Berger and Associates. The building’s curtainwall was fabricated and assembled in Barranquilla, Colombia. The Enclos contract was $76 million, one sixth of the total construction budget. Engineered by Thornton Tomasetti, the building has a reinforced concrete superstructure, link. ↩

-

New York City Planning Commission, Durst Development LLC Application Report, December 19, 2012, 17, link. ↩

-

Via57west, Instagram post, November 10, 2016: “Getting ready to restore and relax with yoga tonight; just one of the many benefits of being a part of the @via57west community! #yoga #newyork #nyc #skyline #swimming #relaxation #architecture #via57west #57west,”link. ↩

-

Steve Cuozzo, “Hudson Market to Open Second Location at 57 West,” New York Post, September 20, 2016, link. ↩

-

David Madden and Peter Marcuse, In Defense of Housing: The Politics of Crisis (Brooklyn: Verso Books, 2016), 117. ↩

-

Jordan Barowitz, phone conversation with the author, October 26, 2016. ↩

-

Binelli, “Meet Architect Bjarke Ingels, the Man Building the Future.” ↩

-

New York City Mayoral Press Release, “Mayor Giuliani Unveils Plan for Development of Far West Side in Manhattan: Study Presents a Revitalized West Side as an Opportunity to Expand the Central Business District,” December 12, 2001, link. ↩

-

New York City Planning Commission, Durst Development LLC Application Report, 13. ↩

-

New York City Planning Commission, Durst Development LLC Application Report, 23. ↩

-

New York City Planning Commission, Durst Development LLC Application Report, 19. ↩

-

Binelli, “Meet Architect Bjarke Ingels.” ↩

-

Barowitz, phone conversation with the author, October 26, 2016. ↩

-

The interview was a part of the New York Times’s “Cities for Tomorrow 2015” conference, July 20, 2015, online at link. ↩

-

Income eligibility is set by the New York City Housing Development Corporation, following federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Area Median Income (AMI) calculations, link. ↩

-

Laura Starr, phone conversation with the author, October 25, 2016. ↩

-

Madden and Marcuse, In Defense of Housing, 12. ↩

Karen Kubey is an urbanist specializing in housing. She curates and produces exhibitions and designs, edits and contributes to publications, and builds and leads public programs. Karen was the founding executive director of the Institute for Public Architecture and co-founded both the Architecture for Humanity New York chapter (now Open Architecture/New York) and New Housing New York.