I

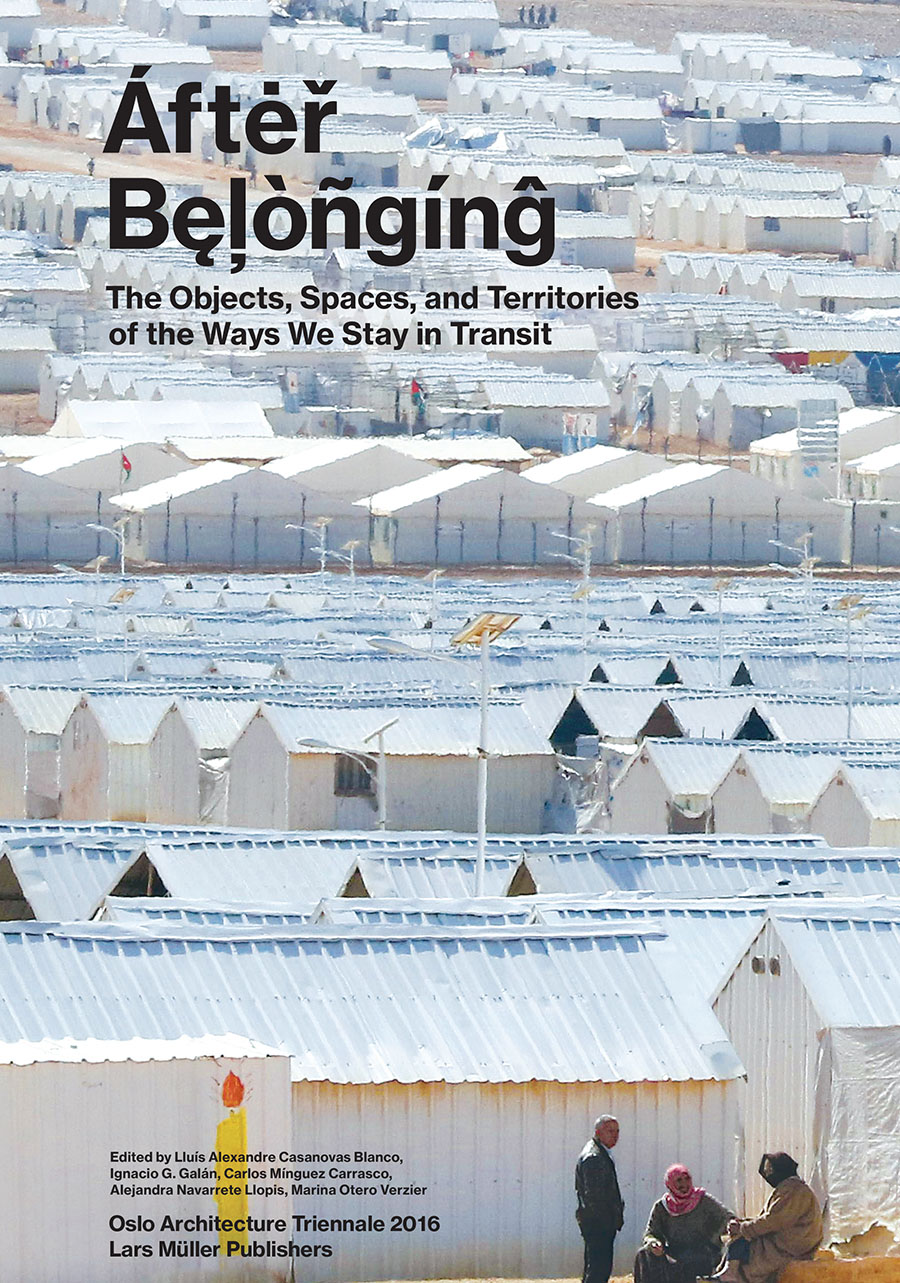

Reviews of the 2016 Oslo Architecture Triennale (OAT), titled “After Belonging: A Triennale In Residence, On Residence, and the Ways We Stay In Transit,” often begin with recalling the travel-induced blur that brought visitors to the exhibition—international flights from major airports, the apparatus of security machinery, entrance into the Schengen Zone, cappuccinos on the train in Norway, then to the airport and onto another flight to leave. This speed-soaked experience of international visitors to the exhibition, including encounters with spatial governance and associated bureaucracies, fittingly reflected its curatorial theme: an investigation of objects and people vis-a-vis “‘freak displacements,’ ‘disjunctures,’ and ‘frictions.’”1 The objects, people, and histories under investigation are seen as always in motion, identifying and identified with multiple constituencies, and affected, for better or worse, by institutions, politics, and capital that move in similar ways. This is the worldview of “After Belonging,” and it is both intoxicating and grim—a transnational assemblage of free-trade zones; the soon-to-be pan-African passport; a ghostly Chinese New Year dragon in Prato, Italy; IKEA’s logistics systems; and the fact that 240 million people live in nations other than the one they were born in.2

In contrast to these montages of foreign conditions, I am reading the catalog/book of the exhibition, also titled After Belonging, while seated at my desk in the US Midwest. My adopted home—alternatively called the Heartland, the Corn Belt, and the flyover states—is a territory in which belonging has often been defined by shared agricultural ecologies and economies of manufacturing, as well as a shared set of similar beliefs. In contrast to the exhibition’s statistic on global migration, according to a Pew study, four in ten Americans have never moved from the place where they were born.3 Can “belonging,” then, be tied to the specificity of place rather than global flows—located at smaller scales such as the watershed or the football team in lieu of EEZs or the EU? These smaller scales have nonetheless been destabilized by the same global forces, which in the Midwest include the extreme expansion and acceleration of agriculture by remote-sensing technology and multinational corporations; the transformation of factory and manufacturing economies by automation; and the ethnic diversification of the region through migration. The heartland is a territory whose voters found in Trump, perhaps, an anchor of a kind of mythical nationalist belonging in the wake of these changes and their associated losses. Trump’s campaign espoused the solidity and enforcement of borders, advocating for the relative stability of geography and one’s place in it. Within the bounds of Chicago, the region’s largest city, conditions of precarious urbanity such as the growing number of vacant lots, buildings slated for demolition, and underserved communities that remain segregated by race and class, also flag how localized and nontransitory conditions of citizenship are of urgent concern.

If After Belonging investigates new modalities of global life “in transit” and the slippage of boundaries under the currents of profit, migration, and communications technologies, then the heartland is a site where we might see how these processes of globalization can touch the ground in sometimes paradoxical ways. The nationalist rhetoric that propelled Trump to victory reminds us of this. According to Felicity Scott’s introduction to the book After Belonging, it “eschews the often-nationalist and identitarian logics within traditional forms of belonging and residence.”4 In the wake of red Make America Great Again hats, nationalism-as-belonging is revealed to be a resurgent and potent force, one that should perhaps be directly reckoned with rather than eschewed.

The flickering between these two ways of seeing the world is the lens through which I read After Belonging. As architects and citizens, if we choose to work in the complex and global register of “after” belonging and the “ways we stay in transit,” do we at times cede discursive space back home to movements such as Trump’s that can espouse very specific, and often narrow, cries of belonging in place? And can we move beyond eulogizing certain models of identity and togetherness with specific actions or intervention that construct, delineate, or support more diverse imaginaries? These questions are more urgent than ever, and After Belonging acts as their agitator. As Nina Berre, chair of the board of OAT, presciently describes: “Our belonging is at stake.”5

II

I began reading After Belonging as a guidebook: as a form of informed (and informing) escapism, on the one hand, since few texts engage the United States and none the Midwest, and as a comparative framework for understanding conditions here at home on the other. At the end of the curators’ introduction, there is an important framing note. “In fact, the ‘After’ before ‘belonging’ cannot be reduced to mean ‘post,’” the five curators clarify. “This ‘After’ in ‘After Belonging’ refers to a search, a pursuit.”6 Read this way, the book’s collection of a dizzyingly broad spectrum of locations, conditions, and scales of work can be seen as a map index within the guidebook, providing multiple potential traveling routes on which we can encounter notable new conditions of community and identity.

The book is divided into five sections: “Borders Elsewhere,” “Furnishing After Belonging,” “Sheltering Temporariness,” “Technologies for a Life in Transit,” and “Markets and Territories of the Global Home.” Each section contains a series of four essay-length texts on the topic by authors from varying disciplines. These essays are each complex and rich and subsequently could be read alone as an edited collection. Their presentation on a yellow background that distinguishes them from the rest of the book allows for this way of reading.

Each section is then followed by six to eight projects, cumulatively titled “On Residence,” that were exhibited in the Triennale. These projects are all illustrated by a few key images and a text that is almost always intriguing, though sometimes mysteriously opaque; these pages serve as entries in an index of works more fully represented in the exhibition. These projects are not “authored” architectural works in the familiar sense—when architects produce a formal proposal in response to a site—but are instead critical analyses and forensic reports. They capture how architectural “tools of its trade” can be used for diagnostics, as well as for speculation. The restrained quality of these works, which almost all stop short of intervention, demonstrate a wary understanding that the built environment is instrumental in how we come together, or alternatively, are kept apart. Because the “On Residence” projects are very diverse in terms of discipline, scope, location, and focus, they can feel unwieldy in their range and yet also entrancingly broad. They include, to name only a few, a site for human rights activism in Lesvos, Greece; monuments on rooftops on destroyed buildings in Syria; temporary accommodations in Madrid; oceanic islands in dispute; the complex section of an international cruise ship.

In each section, bracketing these shorter works are two more robustly presented commissioned projects, part of a series titled “In Residence.” These are reports and projects on certain sites that pertain to each section’s topic, such as Dubai Health Care City; self-storage buildings in New York City; border apparatus in the Oslo Airport; or Kirkenes, Norway, the town on the brink of Arctic extraction economies. At the conclusion of the book, presented outside of the five sections—though they engage the same sites as “In Residence”—there is documentation of five “intervention strategies.”7

Read as a guidebook in search of new ways of coming together, After Belonging represents a collection of distinct, unique stories about the way that “architecture”—understood as “the establishment of protocols negotiating the relations between objects, spaces, and territories [and the] different agents, institutions, and technologies through which they are managed”—can both read and shape togetherness.8 In the wake of the US election, this expanded understanding of architecture responds to the urgent questions that many architects, me included, have been asking: How can we understand the ways in which architecture and the built environment is often complicit or, in fact, instrumental in systems of power with which we, as citizens, may disagree? And alternatively, are there ways that design can have some agency within these contexts without being co-opted?

A few examples in After Belonging highlight how questions of belonging can touch the ground. In Merve Bedir’s text, she describes a soccer stadium and NGO league organized by African immigrants in Turkey. In this popular space, the relationship between “host” and “guest” shifts when team managers come to the popular location to scout talent and organize transfers in the national league.9 In James Bridle’s research, we find a small, ballpoint-pen-drawn qibla arrow orienting visitors to the Oslo Airport’s “Stille Rom” to mecca in lieu of any official signage, an informal gesture transforming the room’s neutrality into useful space for prayer.10 In Pamela Karimi’s research on the Iranian “underground” or “concealed spaces”—which, after 1979, were host to both “conservative Islam … opposing the Shah’s administration” as well as “dissidents,” “revolutionary acts,” “countercultural activism”—a photograph shows a performance by an experimental theater group called AV in an abandoned underground thermal bath: architecture as appropriating an existing space for subversive beliefs and gatherings.11

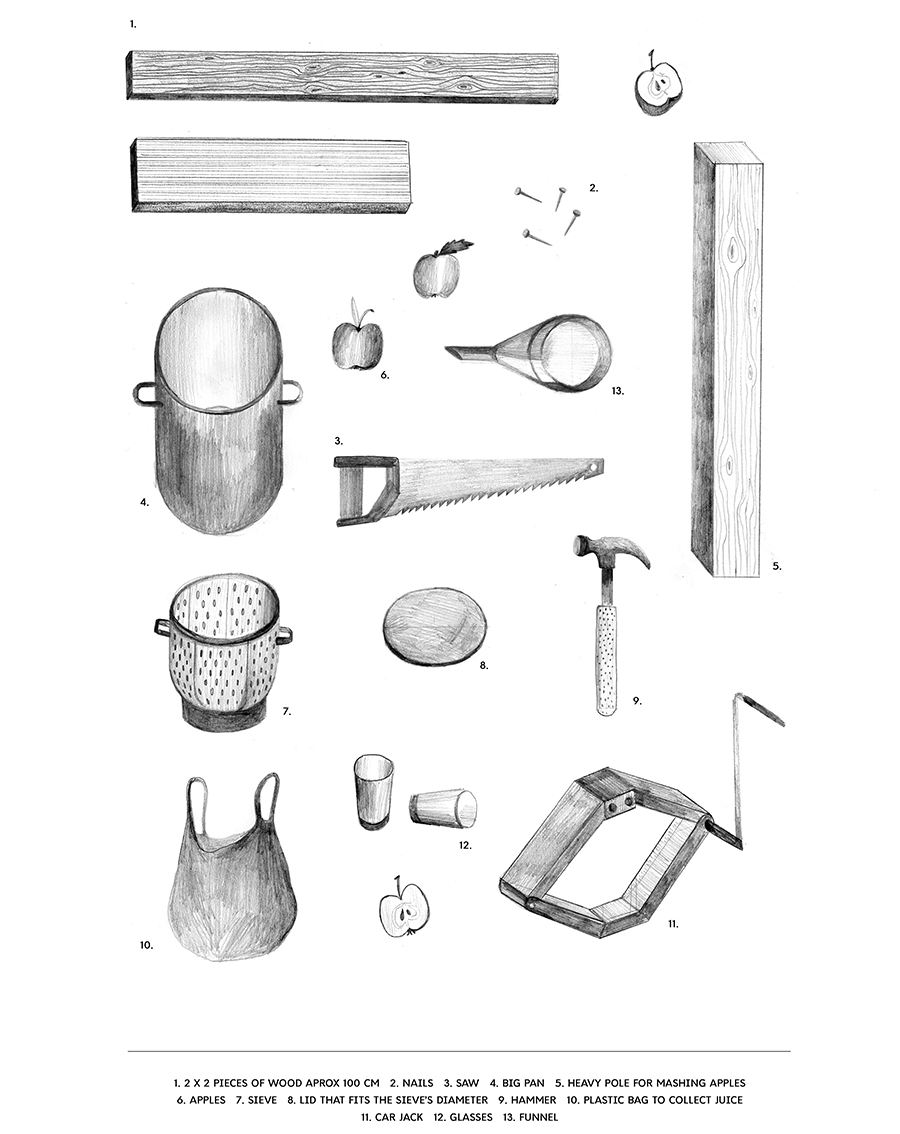

Most simply and poetically, the book describes a heterotopic, previously abandoned, orchard in an asylum center in Torshov, Norway, for Syrian, Afghani, and Iraqi refugees, in which an abandoned fruit grove acts as an “area for collective action and a retreat from daily life.”12 Photographs by Eriksen Skajaa Arkitekter show colorful, abundant green and pink apples, collected by asylum seekers. With a dozen or so tools for an apple press, which were designed by the architects, the asylum seekers share mouthwatering fruit juice that they press together. This architectural intervention is like a poem for how the intersection of space and construction—an orchard and an apple press—can act as a relational set of conditions that both brings people together and offers a mechanism for that togetherness.

“Borders Elsewhere”—which investigates the blurriness of edges, their fluctuation over time, and the ways in which their geographic, architectural, and bureaucratic manifestations express our perceptions of inside and outside, self and other—is certainly timely in the wake of renewed efforts by Trump to construct a US–Mexico border wall. Looking “elsewhere,” as the section’s title suggests, presents more complex conversations. It ultimately redefines the abstraction of the “border” as a thing that is sometimes “wriggling, shapeshifting, foggy, and slippery” and at other times, a political instrument of exclusion and violence.13 Thomas Hylland Eriksen writes on the Roma and Scandinavian travelers—two nomadic peoples who were feared and discriminated against, as well as “envied … for their ethos of freedom and independence.”14 Eriksen refers to an old European engraving that depicts a town, clearly delineated by a wall. Inside are the townspeople; outside, “wild beasts, bandits, and barbarians.”15 More unexpectedly, perched atop the wall is a witch, sitting “spread-eagled” and “grinning.” This witch, in her gleeful subversion of the line that demarcates “us” versus “them,” symbolizes how we fear those who show us the inherent slipperiness of boundaries we understood as stable. Reading Eriksen’s text through the lens of Foucault, one might understand this as only one chapter of a longer tale on the spatial parameters of security and territory: soon, the witch’s walled city (or state or community) is compounded by more insidious systems of control, such as incarceration or mass surveillance. But as the presidential campaign demonstrated, though Foucault’s “society of control” may be our reality, the narrative of inside-versus-out remains potent—it makes for easy tweets and prolific, clickable (and therefore profitable) headlines. “It is nevertheless likely that a major controversy across the continent in the coming years or decades will concern the meaning and implications of the word ‘we,’ that sticky ticket to the realm of belonging,” Eriksen wrote in early 2016.16 Today we brace ourselves instead for an onslaught of these controversies.

Other texts in “Borders Elsewhere” resonate on the eve of Trump’s inauguration: Arjun Appadurai’s text, “Traumatic Exit, Identity Narratives, and the Ethics of Hospitality,” a transcription of a talk given at the Berlin Institute for Integration and Migration in 2015, explores the crisis of citizenship. Appadurai sketches a bleak portrait of contemporary nation-states, in which original conceptions of national identity that rely on “blood, language, religion, location” come into conflict with an era in which refugees and migrants are displaced and relocate precisely because of traumas emerging from those same conditions.17 What does it mean to be a citizen, or an applicant citizen, in the age of “ethnic plurality,” as societies grow more diverse? This is one of the questions at the heart of this section of After Belonging, and Appadurai argues that these flows may be, at their cores, incompatible with old ideas of the nation-state itself, rendering even more combustible the “Make America Great Again” rhetoric.

Appadurai argues that we should look forward to new imaginaries of citizenship and belonging. Beginning to think through these new conditions is a task taken on by “In Residence,” a significant provocation for the architectural discipline at large. “How do we create stories based on imagined future citizenship in a context in which the past (birth, parenthood, and blood) is still the currency of most citizenship laws?” Appadurai asks. “How can longing be turned into belonging? How can hospitality to the stranger be made a legitimate basis for the narrative of citizenship?”18 At my desk in the heartland, I ask in turn: How do we bring these questions about possible futures for citizenship to a broader public—when the narrative of the walled city, neighborhood, or nation protected against the wild beasts outside—has become so powerful? How, as architects, might we set about becoming Eriksen’s subversive grinning witch, both in conversations about borders and walls, as well as in addressing other conditions of spatial governance?

Reading After Belonging as a guidebook means there are also red flags that document how architecture can be deployed in systems of governance and regulation, including how infrastructure and the built environment can be weaponized in the name of belonging. As Scott writes in her preface, “Belonging is a measure at once of inclusion and exclusion.”19 Charles Heller and Lorenzo Pezzani’s contribution “Liquid Traces,” for example, interrogates sixty-three of the 22,000 deaths that have taken place between 1988 and early 2016 on the maritime frontier of the EU, which the authors present as a militarization of the Mediterranean Sea. Their project compared satellite imagery against the data of remote-sensing devices (“optical and thermal cameras, radars”) to show how sixty-three capsized refugees who, fleeing Libya in March 2011, issued distress calls when their boat ran out of fuel. By visualizing the landscape of ships present during the event that were close enough to make a rescue, Heller and Pezzani’s findings argue that these ships’ crews ignored the refugees’ pleas for help, leaving them to die at sea. Keller Easterling’s text “The One, the Binary, the One-to-One, and the Many” studies the strategic, managerial recruitment tactics used by ISIS on the Internet and social media. Easterling’s analysis reveals that ISIS recruiters do not appeal to the teenagers they target with “violence, conflict, and universal dreams,” as one might imagine. Instead they use network infrastructures to appeal to consumerism, affinity for new media (GoPro footage trailers, etc.), a desire for independence, agency for women, and so on—traits that Easterling argues we associate, paradoxically, with the West.

Documentation of temporary shelters sheds light on architecture deployed under the rhetoric of sanitation or stability, which can, conversely, undermine informal communities. In “Architectures of Inhospitality,” Didier Fassin writes on the Calais “jungle,” a refugee camp in France formed of shacks, tents, carts, and poorly draining land from which Syrian refugees would attempt every night to cross the Channel, often returning injured, failed in their attempts, and as victims of violence. Fassin discusses the ways in which the refugees’ self-built urban settlement included “bars and restaurants, barber shops and grocery stores, a mosque and church, a primary store and a legal center”—architectural evidence of ways they orchestrated and organized their living and communal space, even in the worst of conditions.20 He then describes the day that the police arrived to mow down the tents, “hardly leaving” time for the refugees to gather their belongings before they decimated the temporary city, leaving mud and tent fragments in their wake. They then replaced the missing structures with stacks of white shipping-container housing without kitchens or bathrooms, encircled by wire fencing, which the refugees interpreted (perhaps rightfully so) as architectural prisons to keep them from attempting to flee.

Looking at insidious practices outside of conflict zones, Jesse LeCavalier’s text charts IKEA’s 2015 advertising campaign that targeted transitory “young urbanites,” who the ad presented as always between homes and never settling down, carrying furniture down the street and on various forms of public transit in major global cities.21 Exploring the broader systems of logistics and standardization deployed by IKEA, LeCavalier presents an alternative vision of the IKEA consumer as incidentally liberated, perhaps, from traditional domesticity into a new mode of neoliberal belonging, their lives demarcated by IKEA’s international standards, material homogenization, and design for profit.

The timeliness, and potency, of After Belonging’s curatorial theme is captured by the breadth of its scope. The book reveals that issues of inclusion and exclusion, and agency of architecture in both those actions, are strongly felt in extremely diverse places. Additionally, the potent and engaging work that architects, historians, and theorists contributed to this book in response to the theme signals the urgency of the topic across modes of spatial practice. This broadness sometimes leaves gaps—one triennale, after all, can only do so much, and this curatorial project already has captured and commissioned an almost unmanageably large body of works. For me, these gaps include the US Midwest as well as East Asia, including China, where I personally longed to see more work on the transformations of economy and politics and shifts in the rural and urban divide.

Nonetheless, these gaps do not read as oversights. Instead, the scope of the selected texts and five curatorial themes points to them as openings—possible sites of further engagement, a broader call to continue the “pursuit” as positioned in the introduction. In Scott’s preface, she argues that After Belonging “recognizes the sense of urgency or even the emergencies at hand to which architects should respond, and to which architecture might indeed have something important to contribute.”22 Others have read the exhibition’s lack of “traditional” architectural work—that is to say, commissioned, one-off “buildings” with plans, sections, and so on—as a gap.23 This might instead be read as a reflection of the growing sense that the architectural discipline needs to continue to broaden its scope beyond such work, or we risk losing agency in the conversations we find meaningful.

III

After Belonging is a potent guidebook of the complexities of identity and community today, and of divergent practices and agendas of conscientious architects working on these issues. After finishing it, however, my flickering worldviews—caught in the paradoxical ways in which global flows registered in the Midwest during this election through resurgent conversations of nationalist and often exclusionary rhetoric—have left me with a question: what does it mean to “belong” in the United States? Are architects able to craft alternative visions of belonging—of diverse citizenships, of reconsidered communities—and act in tandem with people finding meaning in the places where they live today? In particular, how can we engage the Midwest, where the pains of staying in place—stagnant wages in rural communities where factory jobs have moved overseas or become automated, or trying to secure a mortgage on the South Side against generations of inequitable policies and real estate practices—are often as painful and in need of addressing as the pains of being ceaselessly on the move? Constructing figurative “apple presses,” like those at the asylum center in Torshov, seems to offer one path. Or, more broadly, perhaps we can devise methodologies that allow us to act as the grinning, wall-spanning witch, who subverts the dialectic of us-versus-them by gleefully ignoring the existence of the divide.

-

Various authors, as cited in Lluís Alexandre Casanovas Blanco, Ignacio G. Galán, Carlos Mínguez Carrasco, Alejandra Navarrete Llopis, and Marina Otero Verzier, eds., After Belonging: The Objects, Spaces, and Territories of the Ways We Stay in Transit (Zürich: Lars Müller, 2016), 16. ↩

-

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, “Population Facts: Trends in International Migration, 2015,” quoted in After Belonging, 12. ↩

-

D’Vera Cohn and Rich Morin, “Who Moves? Who Stays Put? Where’s Home?” Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project, December 17, 2008, link. ↩

-

Felicity D. Scott, “Taking Stock of Our Belongings: A Preface,” After Belonging, 25. ↩

-

Nina Berre, “Foreword,” After Belonging, 11. ↩

-

Lluis Alexandre Casanovas Blanco et al., “After Belonging,” After Belonging, 23. ↩

-

These intervention strategies were responses to an open call. A project I did with my partner, titled “Cooperative Arctic Hedge Fund: Investing in a New Constituency in the Far North,” was awarded an honorable mention in this competition. ↩

-

Blanco et al., “After Belonging,” 18. ↩

-

Merve Bedir, “Deconstructing the Threshold: Waste Lands/Trauma/Hospitality,” After Belonging, 53. ↩

-

James Bridle, “Wayfinding,” After Belonging, 68. ↩

-

Pamela Karimi, “Alternative Belongings: Instituting and Inhabiting the Iranian Underground,” After Belonging, 105. ↩

-

Eriksen Skajaa Arkitekter, “The Orchard,” After Belonging, 196. ↩

-

Thomas Hylland Eriksen, “The Destabilized Boundary,” After Belonging, 61. ↩

-

Eriksen, “The Destabilized Boundary,” 63. ↩

-

Eriksen, “The Destabilized Boundary,” 62. ↩

-

Eriksen, “The Destabilized Boundary,” 62. ↩

-

Arjun Appadurai, “Traumatic Exit, Identity Narratives, and the Ethics of Hospitality,” After Belonging, 34. ↩

-

Appadurai, “Traumatic Exit, Identity Narratives, and the Ethics of Hospitality,” 39. ↩

-

Scott, “Taking Stock of Our Belongings,” 24. ↩

-

Scott, “Taking Stock of Our Belongings,” 163. ↩

-

Jesse LeCavalier, “Stuff During Logistics,” After Belonging, 116. ↩

-

Scott, “Taking Stock of Our Belongings,” 30. ↩

-

“There are a lot of abstract installations, projections, and sound pieces to baffle and bemuse,” writes Oliver Wainwright in “Oslo Architecture Triennale: Airbnb Cosplay for the Gig Economy Nomad,” the Guardian, September 12, 2016, link. ↩

Ann Lui is an assistant professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a registered architect in the state of Illinois. She cofounded Future Firm, an architectural practice working at the intersections of landscape territory and curatorial experiments. She recently edited Public Space? Lost and Found (SA+P/MIT Press, 2017), a volume on spatial and aesthetic practices in the civic realm, with Gediminas Urbonas and Lucas Freeman.