Celebrating the mission civilisatrice in Morocco, he praised the instruction, loyalty, and justice brought by the French, as well as the network of roads and the cities they had built—all “signs of civilization.” These achievements, he argued, had created an atmosphere of admiration, enthusiasm, and respect among the Arabs.

—Zeynep Çelik, “Le Corbusier, Orientalism, Colonialism”1

The morning after September 11, 2001, one of my former colleagues at the College of Environmental Design at the University of California, Berkeley, stumbled into his Urban Design graduate seminar. He asked his students how they wanted to conduct class that day: Did they want to have a collective reflection? Did they want to quietly mourn? Would they prefer to cancel class? A gentle silence ensued. And then a student eagerly raised his hand and noted that it was time to discuss how the destruction of the previous day presented an unprecedented opportunity for architects and planners to rebuild Lower Manhattan. While my colleague always narrates this incident with sadness, even disgust, the eager student was not unusual in his professional response to 9/11. Indeed, talk of rebuilding followed rapidly, accompanied by elaborate design competitions and special planning powers. Soon after followed the contracts for reconstruction in Iraq and Afghanistan, distributed alongside the launch of unending war.

Recently, such professional entrepreneurialism was once again on display when the American Institute of Architects (AIA) issued a statement the day after the election of Donald Trump: “The AIA and its 89,000 members are committed to working with President-elect Trump to address the issues our country faces, particularly strengthening the nation’s aging infrastructure.” The statement included a call for unity: “This has been a hard-fought, contentious election process. It is now time for all of us to work together to advance policies that help our country move forward.” The AIA statement was met with a barrage of criticism including a Twitter storm under the hashtag #NotMyAIA. The statement, and the ensuing response, raise vitally important issues about the role of the professions in the age of Trumpism. In particular, the statement is premised on certain ontologies of professional expertise, such as neutrality and innocence. It also asserts the nobility of public interest, of being enlisted in the nation-building work of building infrastructure and of “the design and construction sector’s role as a major catalyst for job creation throughout the American economy.”2

Here, then, are the rituals of normalization, neither mandated nor dictated but rather self-initiated, with enthusiasm, just like that eager design student at Berkeley on the day after 9/11. It is my contention that what is evident in the AIA’s post-election statement is not only a professional interest in Trump’s infrastructure plans but also the infrastructure of assent. We must think critically and historically about this specific infrastructure and its alliances with various forms of power. The design and planning professions along with the field of international development have a long record of complicity with colonialism and imperialism. During the Bush-era wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, I argued that while military occupation itself might generate an ethics of disavowal and refusal, other aspects of American empire, such as reconstruction and foreign aid, often garnered participation from the professions and the global university.3 In turn, such participation has its precursors in the colonial era, in how modern architecture and planning, and related Eurocentric ideas of development, civilization, and progress, were forged in the crucible of colonial rule. In the United States, technologies of planning emerged in the context of Jim Crow segregation and were honed to create and maintain systems of racial separation. What was thus produced was not only the rationale of zoning or the aesthetics of modernization but also assent, specifically a comfortable agreement with racialized power.

The present historical conjuncture requires careful examination of the infrastructure of assent. In the United States, a new political regime is predicated on the valorization of white supremacy, homophobic misogyny, and xenophobic nationalism. On the other side of Atlantic, a vicious politics of chauvinism and austerity also prevail, be it in the Brexit vote or the efforts to expel so-called refugees arriving at the doorstep of Europe. As an ideology, Trumpism is, unfortunately, much more than the Twitter-tantrum-throwing, pussy-grabbing-boasting, tax-evading caricature that is Donald Trump. It is a global phenomenon, one that has been previewed in places such as India, where the Hindu nationalist, Narendra Modi, was elected to power a few years ago.

In the wake of Trump’s election, I have been wrestling with two questions that I have asked myself at various points in my academic career: What is the role of the university in social change? Specifically, what is the role of my discipline and profession, urban planning? As director of a research institute devoted to understanding and dismantling the color lines of our contemporary cities, I now find the endeavor to organize knowledge to challenge inequality, the institute’s initial mission, to be insufficient. We must also build power to challenge violence, including state-sponsored violence against targeted bodies and communities.4 I am willing to grant that Mr. Trump’s win was legitimate and decisive. I grant this legitimacy knowing that the American electoral system has always been “rigged,” be it in the persistence of the Electoral College or in the repeated suppression of the voting rights of racial-ethnic minorities. I do so knowing that Russian geopolitics cast a dark shadow over the American election and meddled in the democratic process. But my specific reason for refusing to recognize the legitimacy of the Trump administration is this: the state that is in the making is an apartheid one.5

There is a lot of talk among leftist scholars about how Trumpism must be viewed not as rupture but rather as a muscular form of previous neoliberal states and their militarized and racialized logics. There is nothing new, my comrades note, in the anticipated rollback of the welfare state or in the state machinery of deportation. The targeting of Muslims here and worldwide, they argue, is not new. Armed mobilization to foreclose black freedom is not new. The denial of human rights to LGBTQ people is not new. American imperialism and its effects on communities reconstituted and renamed as immigrants and aliens are not new. I disagree, for such a framework serves to normalize Trumpism. Not only does the Trump regime portend a systematic dismantling of economic and environmental regulations, a multifront attack on hard-won civil rights, and a significant expansion of state-sponsored violence against people of color and the poor, but also it is poised to codify and implement “a doctrine of racial separation,” W.E.B Du Bois’s phrase in his magisterial book, Black Reconstruction in America.6

If, indeed, what we confront is an apartheid state, then what is our responsibility as scholars, educators, and professionals? I contend that it is a bold and urgent one: to challenge white supremacy, to fight on the front lines of social justice, and to protect the most vulnerable among us. But to do so will require dismantling the infrastructure of assent and instead adopting practices of refusal and resistance. It will require relinquishing the cherished myths of neutrality and innocence and instead deploying the power of knowledge and expertise for the purposes of civil disobedience. It will require being in opposition to state power rather than seeking its patronage. It is my hope that the presidential inauguration marks the initiation of such imaginations and engagements.

“Unbearable Whiteness”

I teach a large graduate class, Histories and Theories of Urban Planning, at UCLA. Two days after the election, my students and I gathered in stunned silence for a teach-in, struggling to find the vocabulary to analyze what we have come to call Trumpism. But name it we must. Because as bell hooks asks, “How can we organize to challenge and change a system that cannot be named?”7 The election has been surrounded by a din of narratives of economic hardship, tales of a Rust Belt working class looking for a salve for the loss of livelihood and status. Yet, most black women and Latinas, two groups hit the hardest by neoliberalization, did not vote for Trump. It is not the “worker” who determined this election but rather the white voter. Indeed, this election has starkly revealed what Michael Dawson calls “the abode of race … hidden in plain sight” notably how the state must mediate “the logics of white supremacy and patriarchy … so that the capitalist economy can function as efficiently as possible.”8 The text I carried with me to class that day was Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction in America, his conceptualization of the white worker and of the wages, public and psychological, of whiteness. In particular, Du Bois argues that while only a small proportion of Southern society owned slaves, the rest, including the “mass of poor whites” who were “economic outcasts” were invested in slavery, including in forms of violence to restrict black freedom.9

On November 10, in our urban planning classroom, we thus named the system we wanted to challenge and change as white supremacy. After all, we had started the quarter reading Kate Derickson’s essay “The Age of Ferguson,” in which she pinpoints the “unbearable whiteness of geography” and considers the prospect of “anti-racist scholarship.”10 All quarter we had sought to break the deafening silence in urban planning history and theory on racial capitalism, American imperialism, and the coloniality of power. But now in a building where the so-called UCLA White Students Group had posted flyers declaring the end of “the governmental strategy” of “an embrace of the replacement of whites, and appeasement of the demands of minority groups,” the naming of white supremacy took on a different and urgent meaning. Like Donald Trump’s insistence during the Hamilton spat that the theater must be a “safe and special place,” such groups are calling for safe spaces for “white voices to be heard.” To break the silence in our disciplines and classrooms by naming white supremacy requires that we enter a radically unsafe space, one that has been the only kind of space that targeted bodies and communities have ever experienced.

But to name and challenge white supremacy, we must acknowledge that our own disciplines and professions are thoroughly implicated in its production and perpetuation. The “unbearable whiteness” of which Derickson writes, the Eurocentrism that I have repeatedly called out in my urban studies writing, is constituted through the elision of such histories. The infrastructure of assent rests on this deliberate silence. It claims what, following Paul Gilroy, we can describe as “an innocent modernity,” “readily purged of any traces of the people without history whose degraded lives might raise awkward questions about the limits of bourgeois humanism.”11 To puncture assent we have to confront that our professions came into being in a world system organized through imperialism, colonialism, and slavery. Thus, in my Histories and Theories of Planning course, I introduce students, training to become urban planners and designers, not to the innocence of modernism and its heroic protagonists but instead to what Gilroy pinpoints as “racial terror.”12 The technologies of modern urban planning, be they zoning or preservation, emerged not in the West but in the experimental spaces of the colonies, under conditions of rule and through the exercise of unlimited political power, often action by decree.

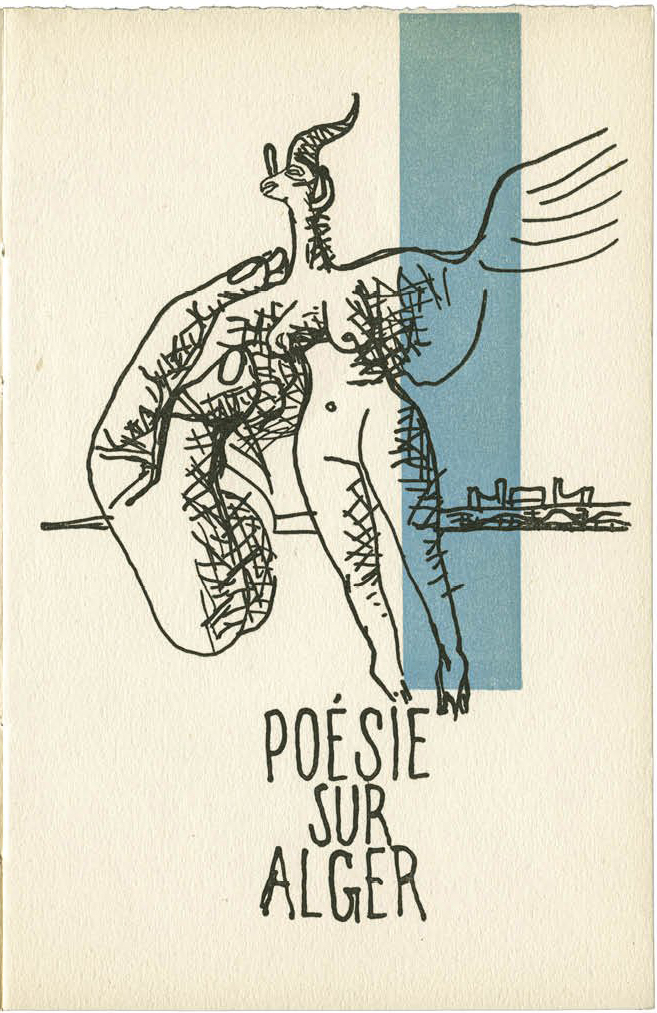

One canonical architectural vision of the modern city, in which difference was managed and regulated, was crafted not in the context of Paris but in occupied Algeria. It is thus that Le Corbusier’s Plan Obus, celebrated by Tafuri as the “most elevated theoretical hypothesis of modern urbanism … the repository of a new scale of values … a means of collective integration,” was at once an expression of colonial rule and of modernism, of mission civilisatrice and racial subordination.13 That the colonial modern was a deeply gendered project is starkly evident in Le Corbusier’s Oriental imaginations and representations, such as the sketch that forms the cover of his essay, Poésie sur Alger, the hand of the master architect caressing the semihuman, feminized body of the city/colony.

As Çelik notes, Le Corbusier repeatedly associated his architectural designs with the body of Algerian women, likening Algiers itself to “a magnificent body, supple-hipped, and full-breasted.”14 It is in relation to such colonial articulations that Fanon’s revolutionary vision, expressed in A Dying Colonialism and situated in the dual city created through colonial architecture and planning, must be read:

The Algerian woman who walks stark naked into the European city relearns her body, re-establishes it in a totally revolutionary fashion. This new dialectic of the body and of the world is primary in the case of one revolutionary woman.15

I worry that teaching and learning these histories is not sufficient to shake up assent. Our pedagogies are far too polite, our canonical textbooks are far too genteel. I teach, as many do, about how, in the United States, technologies of planning, from racially restrictive covenants to Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) maps, were implicated in the production of segregation. Put another way, if we are to think with Michelle Alexander about the enduring racial caste system in America, then we have to think about how urban planning has played a role in perpetrating and remaking the spatialities of racial caste.16 But my list of techniques and technologies obscure the embodied violence that was required to deploy these technologies, to actually hold the color line. And in this way I, too, replicate the trope of innocent modernity and prop up the infrastructure of assent. What if we were to start instead with an image such as the chilling Panel 15 of Jacob Lawrence’s Migration of the Negro series?

Its caption reads: “Another cause was lynching. It was found that where there had been a lynching, the people who were reluctant to leave at first left immediately after this.” What if this were our pedagogy of space and body: the cold and bleak landscape, the hunched figured, the lynched body, striking in its absence? It is perhaps with such a scene in mind that Billie Holiday sang “Strange Fruit”:

Southern trees bear a strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant South

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth

Scent of magnolia sweet and fresh

Then the sudden smell of burning flesh.

Rebecca Ferguson, asked to perform at Donald Trump’s inauguration, has said that she will do so only if she can sing “Strange Fruit.” What is our version of “Strange Fruit” in architecture and planning?

From Diversity to Divestment

The AIA post-election statement, as I have already noted, was met with widespread criticism. In response, the AIA issued a new statement, one that emphasized that the AIA “will continue to be at the table and be a voice for the profession, especially when it comes to diversity, equity, and inclusion.” Indeed, Diversity, Equity, Inclusion is the new bureaucracy of liberal integration, prominent at our global universities. Emerging from the civil rights struggles of the 1960s, from the fierce efforts to create space for fields of inquiry that challenge Eurocentrism, such as ethnic studies, these bureaucracies have replaced rage with assent and civil disobedience with civility. Most of all, they express a call for a unity that transcends difference. Note the language of the Division of Equity and Inclusion at the University of California, Berkeley: “to build a campus where there are no ‘others.’”17

Such visions abound in the post-election moment. We are surrounded by hand-wringing about identity politics. We are told that being American must trump the experience of being female or black or LGBTQ or Muslim or undocumented, of being other. Unity, not identity, is the call of the day. Indeed, identity politics was a decisive force in Trump’s victory: white identity politics, as Michael Eric Dyson writes, “white identity masked as universal, neutral, and, therefore, quintessentially American.”18 Unexamined, unbearable whiteness. If we were to examine whiteness, then we would have to acknowledge otherness. Historical difference, i.e., difference constituted through the long histories of imperialism, colonialism, and slavery, cannot be wished away through the liberal solution of integration. And if we were to examine whiteness, then we would have to acknowledge the persistence of exclusion rather than the promise of inclusion. As an urbanist whose recent research is concerned with property and personhood, I am inspired by Cheryl Harris’s landmark Harvard Law Review essay, “Whiteness as Property,” in which she traces “the evolution of whiteness from color to race to status to property” and notes that both whiteness and property entail “a right to exclude.”19 And if we were to examine whiteness, then we would have to shift our professional commitments from the bureaucracies of diversity to the politics of divestment.

I came of political age in the era of divestments and sanctions, many of them leveled at apartheid regimes such as those in South Africa and Israel/Palestine. By contrast, I have watched the normalization of the Modi regime in India, often under the banner of good governance, the frenzied support of an Indian diaspora for right-wing nationalism, and the acquiescence of North Atlantic leaders to Hindu fundamentalism for the sake of global capitalism and geopolitical alliances. What will be our allegiance to the apartheid state that Trump is intent on constructing? What are the conditions we at global universities are willing to accept for our share of Title VI dollars or Department of Defense research awards? Will we claim neutrality? Will we invoke expediency? Will we assert the nobility of public interest, as did the AIA’s initial post-election statement on infrastructure? Already at many universities, including my own, there is a scramble to demonstrate relevance to the Trump administration, to produce the white papers that will align research priorities with those of the new regime.

I do not believe that such relevance and alignment is ethically possible. My call for divestment is thus an insistence on disobedience, refusal, and resistance. In previous work, I have examined the praxis of architecture and planning by invoking the concept of the double agent. The idea of doubleness derives from David Harvey who conjures up the figure of the insurgent architect, “as a cog in the wheel of capitalist urbanization, as much constructed by as constructor of the process.”20 The idea of doubleness, specifically of a “double consciousness,” is also powerfully articulated in black cultural studies, for example in the writings of DuBois and as outlined in Gilroy.21 Reflecting on praxis in the time of empire, I have previously suggested that it is possible to consider the simultaneity of complicity and subversion. The double agent is one who is embedded in systems of power and yet is able to stage moments of rebellion against and within such systems.22

But I am not convinced that doubleness will suffice as an ethics of profession and personhood at our present moment. Instead I am inspired by the call issued by Jonathan Massey, one of a handful of architecture deans asked to comment on Trumpism in the wake of the AIA statement. Dispensing with the genteel vocabulary of diversity, Massey notes that the statement “aligned the AIA with whitelash, since infrastructure for Trump begins with a border wall supposed to secure white prosperity through racial exclusion.” Dispensing with the infrastructure of assent, Massey insists that there “is some work an architect must refuse.” He asks, “Would you design Trump’s wall? How about a border station for his Homeland Security Department? A conversion therapy clinic?” Massey concludes that “withholding our labor is architectural agency in one of its strongest forms.” In the place of the AIA’s cause of public interest and national infrastructure, he calls for “a profession that serves justice” as “an infrastructure worth building.”23

To do so, we have to reconsider the boundaries of our professions. What are the forms of rogue expertise to which we will contribute? The data refuge efforts that are under way in order to protect key climate data from the Trump administration are one example.24 In what ways will we mobilize the power of the university to actively challenge Trumpism? Our modest efforts to declare January 18 as a day to Teach.Organize.Resist is one example. In what ways will we ally with social justice movements to plan and sustain alternative visions of space and society? Robin D. G. Kelley reminds us that what the Movement for Black Lives provides us, for example in their recent document, “A Vision for Black Lives: Policy Demands for Black Power, Freedom, and Justice,” is “less a political platform than a plan for ending structural racism, saving the planet, and transforming the entire nation—not just black lives.”25 I would like the AIA and APA to pledge support for this plan. That is the statement I eagerly await.

In dark times I often turn to James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time. Published in 1962, it contains the extraordinary letter, “The Dungeon Shook, Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation.” Baldwin writes, “If the word integration means anything, this is what it means: that we, with love, shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are, to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it … You come from a long line of poets … One of them said, The very time I thought I was lost, my dungeon shook and my chains fell off.”26

No one has chained us, but we are in chains. It is time to shake the dungeon and leave behind these chains.

Portions of this piece were originally published as “Divesting from Whiteness: The University in the Age of Trumpism,” Society + Space, November 28, 2016.

-

Zeynep Çelik, “Le Corbusier, Orientalism, Colonialism,” Assemblage 17 (April 1992): 66. ↩

-

Among other publications of this statement, see “AIA CEO Robert Ivy Comments on Presidential and Congressional Election Outcomes,” Architect Magazine, November 9, 2016, link. ↩

-

Ananya Roy, “Praxis in the Time of Empire,” Planning Theory, vol. 5, no. 1 (2006), 7–29. ↩

-

See Ananya Roy, “From Color-Lines to Front-Lines: Organizing to Challenge Violence,” November 16, 2016, link. ↩

-

See also my “Divesting from Whiteness: The University in the Age of Trumpism,” Society + Space, November 28, 2016, link. ↩

-

W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880 (1935; New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 573. ↩

-

bell hooks, The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love (New York: Atria Books, 2004), 25. ↩

-

Michael Dawson, “Hidden in Plain Sight: A Note on Legitimation Crises and the Racial Order,” Critical Historical Studies, vol. 3, no. 1 (Spring 2016), 161, 145. ↩

-

Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, 25. ↩

-

Kate Derickson, “Urban Geography in the Age of Ferguson,” Progress in Human Geography (2016), link, 7. ↩

-

Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1993), 44. ↩

-

Gilroy, The Black Atlantic, 73. ↩

-

Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1976), 133. ↩

-

Çelik, “Le Corbusier, Orientalism, Colonialism,” 71. ↩

-

Franz Fanon, Studies in a Dying Colonialism, trans. H. Chevalier (New York: Grove Press, 1965), 59. ↩

-

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: The New Press, 2012). ↩

-

UC Berkeley Division of Equity & Inclusion, http://diversity.berkeley.edu. ↩

-

Michael Eric Dyson, “What Donald Trump Doesn’t Know about Black People,” the New York Times, December 17, 2016, link. ↩

-

Cheryl Harris, “Whiteness as Property,” Harvard Law Review, vol. 106, no. 8 (June 1993): 1,780. ↩

-

David Harvey, Spaces of Hope (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 237. ↩

-

Gilroy, The Black Atlantic, 126. ↩

-

Roy, “Praxis in the Time of Empire.” ↩

-

Jonathan Massey, quoted in Amelia Taylor-Hochberg, “Dean’s List Special: How Architecture School Leaders are Responding to Trump,” Archinect, December 6, 2016, link. ↩

-

Robin D. G. Kelley, “Trump Says Go Back, We Say Fight Back,” Boston Review, November 15, 2016, link. ↩

-

James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time (1962; New York: Vintage International, 1993), 10. Emphasis in the original. ↩

Ananya Roy is professor of urban planning and social welfare and inaugural director of The Institute on Inequality and Democracy at UCLA Luskin. She holds the Meyer and Renee Luskin chair in inequality and democracy. Roy’s most recent book is the coauthored volume Encountering Poverty: Thinking and Acting in an Unequal World (University of California Press, 2016).