The island of Manhattan is slowly tilting toward Hudson Yards. When completed, the project will have added 17 million square feet of residential and commercial space, 14 acres of public open space, 100 shops and restaurants, a cultural space, luxury hotel, and public school.1 We’ve grown familiar with the ingredients that go into making this kind of urban development soup: sustainable design, infrastructure upgrades, and a mixture of retail, commercial, and residential space. And of course, no description of the new development’s impact on the urban economy is complete without detailing the amenities offered back to the city’s residents: open space, affordable housing, and a self-aware carbon footprint.

Discrete development projects like Hudson Yards continue to pepper the urban landscape, manifestations of privileged infrastructure systems and accompanying capital flows that reshape the city into “splintering urbanism.”2 Such revitalization projects rely on the myth of the ideal city as economically vigorous, perpetually growing, and self-sustaining. “Urban competitiveness,” David Wachsmuth writes, “is a key phrase describing entrepreneurial urban governance oriented toward attracting globally mobile capital investment as a means of economic survival.”3 4 The city—described by Wachsmuth as an ideological construct as much as a site where this kind of financial exchange takes place—demands its piece of the global capital pie. Constructing the image of the city rests on an economic framework. As the state continues to implicate itself in entrepreneurial governance in order to stake a competitive edge, one might ask: Who’s governing whom?

There is much to be discovered in the space between what design is intended to do and what it actually does. Related Companies, the main real estate firm behind the Hudson Yards development, “is staunchly committed to sustainable design.”5 What then, exactly, is sustainable design? And how does sustainable design fit into other discourses on sustainability in the city? The United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development recognizes that sustainability must move beyond environmental and energy metrics. Of the seventeen goals listed, its first five include “no poverty, zero hunger, good health and well-being, quality education, and gender equality.”6 At times overlapping with, and at times a substitute for, terms like resilience, green design, adaptability, urban ecology, and environmental responsiveness, among others, sustainable design is as complex as the context out of which Hudson Yards is now emerging.

The Sustainability of the Private

One thing that is surely being sustained at Hudson Yards is the public funding of private ventures. For anyone doubting the level of engagement between the state and business, consider that about $3 billion in taxpayer money was poured into infrastructure improvements targeted toward Hudson Yards in order to entice investment. Indeed, this prompted Stephen Ross, chairman of Related Companies, to proudly inquire, “Where else have you ever seen this kind of public money for infrastructure to service a whole new development, in the heart of the city, with that much land and no obstacles?”7 The answer has been, in recent years, not New York.

Within this whirlwind of development, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), owner of the twenty-six-acre Hudson Yards site, is, for the first time, using real estate to secure its debt, raising over $1 billion in bonds backed by expected returns from lease agreements with Related and Oxford.8 As a public-benefit corporation, the MTA is exempt from state regulations that limit the debt it incurs, allowing it to take on risky high-cost public works projects.

Amphibian public-private institutions, such as the MTA, are increasingly harder to tell apart from their stricter public counterparts, such as the City of New York. Emerging as a reaction against the laws and regulations that apply to public organizations, the projects they take on manifest in our surrounding built landscape while operating within a relatively loosely regulated private arena. This interdependent relationship forces us to ask what, exactly, the role of government is in regulating development and furnishing civic infrastructure.

The Public-Private-Partnership Knowledge Lab of the World Bank Group admits that it is difficult to define the public-private partnership. Their published reference guide defines it as a “long-term contract between a private party and a government entity, for providing a public asset or service, in which the private party bears significant risk and management responsibility, and remuneration is linked to performance.”9 As we collectively sit back and wonder what shape our ever-evolving government will take in the next four years, from the national scale to the local, this much is clear: in calling for regulatory reform task forces, the perceived threat of regulations on the economy is one of the primary concerns for the current administration.10 Economic interests are almost synonymous with private business interests, and the question of what the public gains in return from public-private partnerships is murky territory.

The Sustainability of Urban Renewal

Every mayor in New York since the 1970s attempted to jump-start development in Hudson Yards. Most recently, in January of 2005, the land between Twenty-Eighth and Forty-Second Streets and Eighth and Twelfth Avenues was rezoned from industrial to mixed-use residential and commercial (MTA’s railyards run from Thirtieth to Thirty-Third Streets and Tenth to Twelfth Avenues). The extension of the No. 7 line was proposed in the mid-2000s alongside plans to build a new Jets Stadium over the railyards as part of a strategy to secure the 2012 Summer Olympics. At the time, the MTA did not have the funds available to move ahead with the extension, and following the defeat of the new stadium proposal the MTA solicited bids for a mixed-use development from developers.

Meanwhile, funding for the No. 7 line extension was under way through speculation on future property development. In 2006, under Mayor Bloomberg, the MTA raised the $3 billion required for the No. 7 line extension to Hudson Yards through New York City funds raised by the sale of Tax Increment Finance bonds. These bonds were to be repaid using revenue received from property taxes tied to any future development served by the No. 7 train extension. In December of 2009 the Western Rail Yard was included in an official mixed-use rezoning effort, and Hudson Yards offered a District Improvement Bonus that exchanged higher density with public amenities.11

The management of the environment cannot be thought of in isolation of land use questions and, in turn, planning. Hudson Yards therefore situates itself squarely in the middle of the set of questions circling around the role of the state, and, by extension, of planning in public-private partnerships. Planning distances itself from the real effects of urban renewal projects and (seemingly) focuses, instead, on codes, policies, and regulations. As Nicholas Blomley points out:

True to its utilitarian roots, planning has no particular interest in the morality of property on its own terms, but rather concerns itself with the results of property, and the degree to which these are beneficial or useful … Re-zoning hearings in inner city neighborhoods, struggling with marginalization and gentrification, hear residents’ claims—centered on collective rights to not be excluded, and appeals to indigeneity and colonialism—politely but totally rebuffed by the depoliticizing discourse of setbacks, building heights, and car parking requirements. Density, it seems, nullifies justice.12

Since the turn of the twentieth century, planning regarded the city, particularly its industrial zones, as a series of damaged environments. Mapping, or zoning, the city based on these utilitarian assessments provided the impetus planning needed to perpetuate urban renewal projects. Arguably, one of Robert Moses’s largest legacies in urban planning history was not his transformation of New York City but rather that he set the stage for urban regeneration as a standard method of modernizing and organizing the city, sequestering land where appropriate and casting state authority as independent of the city’s inhabitants in the name of efficiency.

The Sustainability of Finance

Hudson Yards is America’s largest private real estate development. Once completed, Related Companies, the major stakeholder in the project, estimates it will add 2.5 percent to New York City’s domestic product.13 Hudson Yards is estimated to cost the developers $20 billion. And Related’s Stephen Ross is securing commercial tenants at project cost—the first of whom were Coach and L’Oréal—in order to finance the retail and residential portions of the project, where he aims to make his profit.14

Ross, trained as a tax lawyer, was catapulted into the world of development through profit-generating affordable housing. Equipped with $10,000 from his mother and nearly 100 percent financing from state housing agencies that administer federal government affordable-housing tax credits, Ross entered the affordable housing market and amassed wealth by “syndicating and selling tax shelters that accompanied the projects to wealthy investors.”15 By the 1980s, Ross’s dealings were responsible for adding about five thousand affordable units to New York City’s housing stock.16 Today, he is also the founder and chairman of CharterMac, a company that is insulated from boom and bust economic cycles by providing a steady source of income through investments in tax-exempt bonds that help finance low-income housing.17 Though the intricacies of federal programs related to affordable housing may have changed since the 1980s to today, “their premise has stayed the same: private developers will build and preserve affordable rental housing if they are given adequate tax breaks.”18

Outside of the United States, Related Companies now has offices in two other locations: Abu Dhabi and Shanghai. Related’s reliance on Chinese capital for funding its real estate endeavors seems to have grown in recent years. Not incidentally, in the early 2000s, Related opened factories in China to produce the curtain walls, among other materials, that are being used now to build Hudson Yards, drastically reducing costs and eliminating middlemen.19

By around 2013, after Related Companies and Oxford Properties Group secured the Hudson Yards development, Related sought out EB-5 financing as banks continued to withhold funds for construction amid economic stagnation. The EB-5 program, also called the Immigrant Investor Program, was established by Congress in 1990 and is meant to stimulate economic growth in critical areas by matching investor funds with local projects. It does so by confirming a foreign investor’s eligibility to apply for a green card provided they invest in a commercial enterprise and prove they can create or maintain at least ten permanent jobs for U.S. workers.20 In exchange for permanent residency, the investor agrees to a low interest rate for their loan, to be paid back within a few years. Typically, a broker acts as the liaison between the program and the investors, and regional centers bundle those investments for a project to commence. Related, on the other hand, directly procures foreign, particularly Chinese, investors through events “ranging from a gala featuring a Chinese television personality and flamboyantly dressed dancers to more mundane PowerPoint presentations.”21

The EB-5 program is intended to stimulate the economy specifically in low-income neighborhoods across the United States. Therefore, in order for a project to qualify under EB-5 financing, it must meet the Targeted Employment Area guidelines for unemployment in the project area. Initially, Hudson Yards did not meet the unemployment rate to warrant this financing. But, as Eliot Brown’s investigative reporting has revealed, New York State’s gerrymandering added census tracts to the Hudson Yards project in order to qualify the project.22

Related was able to raise $600 million for the initial phase of the Hudson Yards development through EB-5 and is aiming to raise another $600 million.23 In a $20 billion project these amounts don’t add up to much but do lead to a pertinent question: How much of the $20 billion was amassed through federal programs meant to distribute economic well-being equitably rather than concentrating it in a commercial enterprise zone? In a political landscape that asks the citizen to step aside to give room to the developer to exercise his or her “private risk,” it is worth asking just how much of that risk is, indeed, private.

The Sustainability of the Public

Related Companies present plans promise an open and diaphanous set of sparkling buildings, plazas, parks, sculptures, pathways. Anyone, big or small, black or white, freak or vanilla, can walk on its tiled paths and take in this tepid micropolis. Theoretically, at least. After all, access to privately owned public space by the public is contingent on how the stewards of such spaces define who belongs in the public.

“We want this project to be laced through with public streets, so that everyone has ownership of it, whether you’re arriving in your $100,000 limo or pushing a shopping cart full of your belongings,” David Childs, partner at SOM—the firm designing Hudson Yards— insists.24 New York City’s 1961 Zoning Resolution aimed to incentivize the private development of public space by relaxing high-density restrictions for developers. Over 3.5 million square feet of public space were consequently added to the city, distributed among over five hundred locations.25 According to a study of over five hundred privately owned public spaces in New York City published in 2000, despite their public status such spaces are actively managed by surrounding tenants and management groups as if they were private.26

What, then, is public space in Hudson Yards? It is as powerful an agent as the buildings themselves are. If we shift our focus from how the individual parcels and buildings are zoned to how this development connects to its global context, we see the emergence of what Keller Easterling defines as “infrastructure space,” which, while material, is hidden and silent. “Some of the most radical changes to the globalizing world are being written,” she writes, “in these spatial, infrastructural technologies—often because market promotions or prevailing political ideologies lubricate their movement through the world.”27 In this context it is often the recognizable characteristics of “public space” that make it seem so: it looks public; therefore, it is public. Plazas with benches open up to cafés and retail arcades. Pulsating with people who seem intent to consume, the public space is one that you go to to plug into the larger flow of investment, capital, and an image of urban lifestyle.

The Sustainability of Energy Use

Hudson Yards is dizzying in its list of interconnected technologies, a system rather than a set of buildings. Shannon Mattern offers a thoughtful account of the data-driven infrastructure that the Hudson Yards development promotes as sustainable design. “While such systems are environmentally ‘smart’—they eliminate noisy, polluting garbage trucks; minimize landfill waste, and reduce offensive smells—they also cultivate an out-of-sight, out-of-mind public consciousness,” Mattern explains.28 Our definitions of sustainability tend to act like putty, stretching and squeezing to fill the holes in our ecological thinking so that we can get to a holistic picture of what it means to live responsibly on our planet. The aesthetics of sustainability emerge from the urgency to suppress, cover up, and ultimately control our environment.

Similarly, the aesthetics of the Hudson Yards project are part and parcel of its sustainable design, “a triumph of culture, commerce, and cuisine; a technological marvel that pairs style with sustainability.”29 Thanks to “smart” technology, residents and tenants will be connected to an energy-monitoring system, curbing consumption inefficiencies. Thad Sheely, senior vice president of operations at Related Companies, admits that this may be something we will have to wait for. Hudson Yards is laying down the infrastructural foundation in order to collect energy data, even though they’re not quite sure what to do with it all yet. He explains, “There’s something here, but Google and Apple haven’t figured it out yet, either. But this is a road we have to be on, but no one knows where it goes … our focus has been to get the hardware right, so that we have the bandwidth, the connectivity, two-way communication, and the ability to upload and download and collect data.” 30

The project is so far ahead of itself; it hasn’t yet caught up to its promise, though this kind of data collection is fundamental in the design of Hudson Yards. The infrastructure of energy use monitoring is not simply integrated into the project but is an active agent in shaping and designing the buildings, open spaces, and even natures that comprise this development. With the thumbprint swipe of a screen one can reflect on their participation in Hudson Yards, coded through the metrics of energy use. Hudson Yards is as much space as it is interface, with all of the potential impacts (foreseeable and unforeseeable) that this entails.

The development’s cogeneration capacity will reach 13.2 megawatts, and the buildings, interconnected, will share heating and cooling resources. Trash will be sucked away at forty-five miles per hour through a pneumatic tube system.31 LEED-accredited building envelopes will protect inhabitants from the city’s environmental hazards, as operations managers will be able to look through patterns of energy use, traffic, and pollution, among others, and react responsibly with just the right measure of efficient restraint. Waste separation systems on site will help divert organic waste from landfill by converting it to fertilizer, while about ten million gallons of water will be actively managed on site each year.

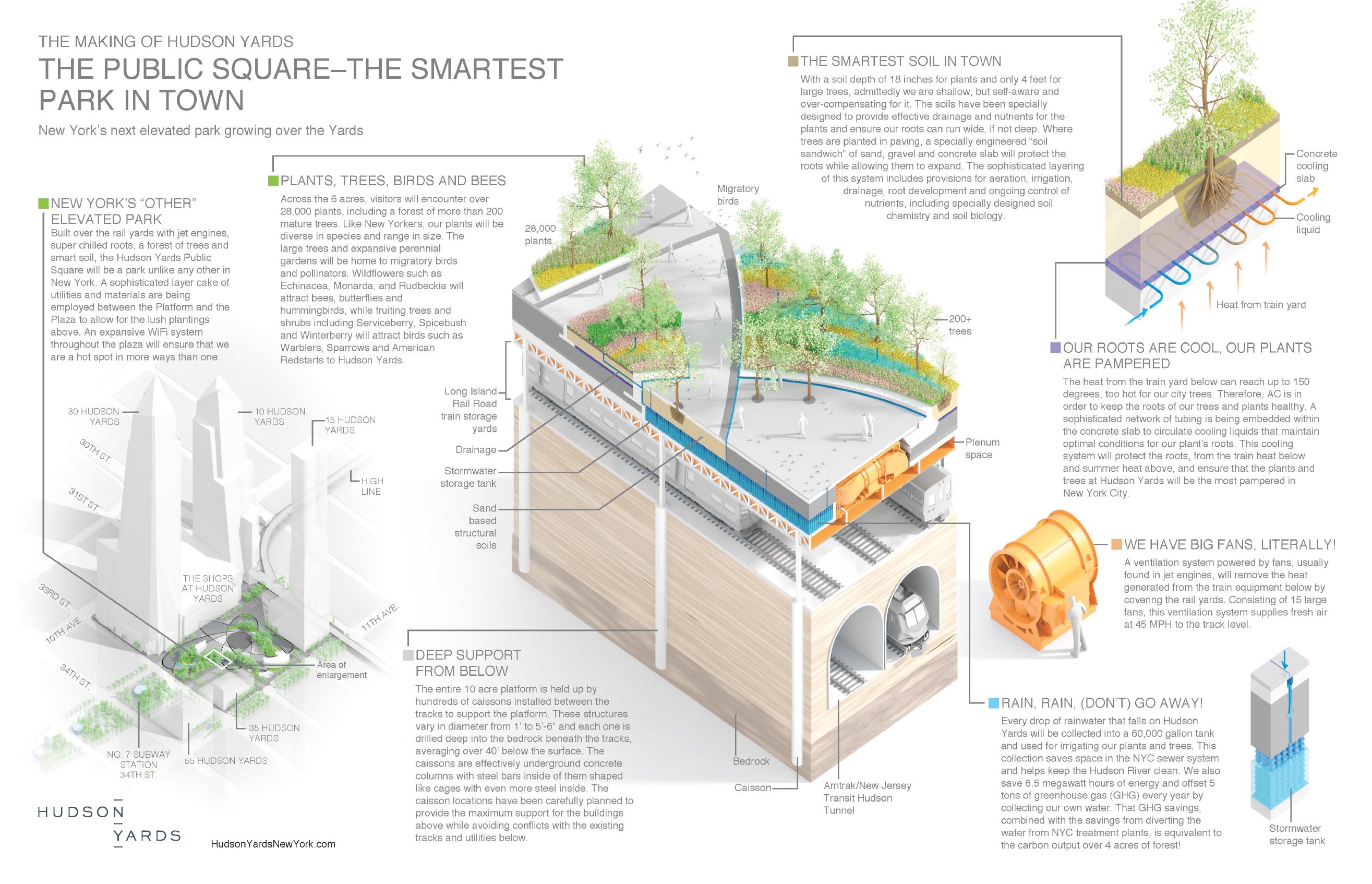

An island on top of land, Hudson Yards is built on a platform that hovers above the LIRR rails. The meticulous caisson placement between the tracks below allows the trains to continue their itineraries uninterrupted while construction above continues. The truss above the tracks, up to eight stories deep in some locations and requiring thirty-five thousand tons of steel and fifty thousand cubic yards of concrete, provides the structural support for the buildings above.32 Atop the truss is a public plaza, what Related and Oxford call “the smartest park in town.”33 Spanning six acres, it will contain plantings that range from a few inches to seven feet in depth. While the developers celebrate the upcoming “return of nature” to New York City through the Hudson Yards green plaza, it is estimated that the heat from the trains below will raise the temperature of the plaza soil up to 150 degrees, which will then need to be cooled off in order for the plants to stay alive.34 The nature-in-the-city image of sustainability is so much more potent than the energy demanded to uphold that image that the energy production process is refashioned into an engineering accomplishment: “Most parks have trees and flowers and shade. Ours has jet engines. (And super-chilled roots, a forest of trees, and really smart soil.)”35

What these sustainable aesthetics and rhetorics of efficiency occlude is the messy and vital public that is excluded from a publicly funded private development—the many, many New Yorkers that real estate projects like Hudson Yards do not sustain. The aesthetic of sustainable design is an easier sell, and easier signifier, than the more complex and invisible changes to development that could otherwise move toward environmental and social equity. Walking through a quasi-paved zone with trees meticulously placed along a windy path in the name of sustainable development, for instance, registers more visibly than diverting funds toward a more efficient use of water in agriculture production.

As a set of technological and rational ideas meant to move a city forward, modernism persists. The city continues to be managed as a machine even when it is likened to an ecology, holding the promise of an explicit spatial order that needs to be restored in order for urban health to be maintained. Concerns surrounding equity, sustainability, and the environment, entering mainstream development discourse relatively recently, are subsumed within the perception of the city as economic engine of growth.

As the Hudson Yards project underscores, the process through which the image of sustainable development is upheld is not neutral. Rather than focusing on the city as an artifact of an urbanization process, evaluating the process of urbanization itself requires pulling in the economic, political, environmental, and social movements that shape urban design and development. Seen through this framework the goals of sustainable development dissipate, weak and tenuous against the backdrop of powerful shifts in institutional relations and financial flows that give form to such development.

Governing agencies facilitate this kind of spatial management, as they shed their regulatory clothes and button up their entrepreneurial suits. Alongside this ongoing transformation, Hudson Yards tells us that the myth of sustainable development is not only alive and well but recast onto the planning field as thoughtful urban ecology.

-

“First Hudson Yards Tower, 10 Hudson Yards, Tops Out,” Hudson Yards New York, link. ↩

-

Stephen Graham and Simon Marvin, Splintering Urbanism (New York: Routledge, 2001). ↩

-

David Harvey, “From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation in Urban Governance in Late Capitalism,” Geografiska Annaler, Series B, Human Geography, vol. 71, no. 1 (1989): 71. ↩

-

David Wachsmuth, “City as Ideology: Reconciling the Explosion of the City Form with the Tenacity of the City Concept,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 32, no. 1 (February 2014): 86. ↩

-

“Sustainable Development Goals—United Nations,” United Nations, link. ↩

-

Justin Davidson, “From 0 to 12 Million Square Feet,” New York Magazine, link. ↩

-

Keiko Morris, “Ratings Firms Give High Marks to MTA Bond Offering,” Wall Street Journal, link. ↩

-

David Shepardson and Steve Holland, “In Sweeping Move, Trump Puts Regulation Monitors in U.S. Agencies,” Reuters, February 24, 2017, link. ↩

-

“Rezoning—Hudson Yards Development Corporation,” the City of New York, link. ↩

-

Nicholas Blomley. “Land Use, Planning, and the ‘Difficult Character of Property,’” Planning Theory & Practice (2016): 1–14. ↩

-

Morgan Brennan, “Stephen Ross: The Billionaire Who Is Rebuilding New York,” Forbes, March 7, 2012, link. ↩

-

Brennan, “Stephen Ross.” ↩

-

Brennan, “Stephen Ross.” ↩

-

Alex Frangos, “Affordable-Housing Empire Fuels Developer’s Upscale Aims,” Wall Street Journal, August 22, 2006, link. ↩

-

Frangos, “Affordable-Housing Empire Fuels Developer’s Upscale Aims.” ↩

-

Brennan, “Stephen Ross.” ↩

-

“EB-5 Immigrant Investor Program,” Department of Homeland Security USCIS, link. ↩

-

Eliot Brown, “How a U.S. Visa-for-Cash Plan Funds Luxury Apartment Buildings,” Wall Street Journal, September 9, 2015, link. ↩

-

Brown, “How a U.S. Visa-for-Cash Plan Funds Luxury Apartment Buildings.” A 2013 letter obtained by Brown through the Freedom of Information Act, written by a New York State labor official and addressed to a state economic-development agency, offered an alternative boundary that would meet the minimum unemployment threshold. Brown’s research further found how Hudson Yards was named a project of “national interest” in order to expedite the release of funding for the project. For more on this, see Eliot Brown, “Is Hudson Yards In the ‘National Interest’?” Wall Street Journal, September 10, 2015, link. ↩

-

Brown, “How a U.S. Visa-for-Cash Plan Funds Luxury Apartment Buildings.” ↩

-

Justin Davidson, “From 0 to 12 Million Square Feet,” New York Magazine, October 7, 2012, link. ↩

-

Jerold S. Kayden, Privately Owned Public Space: The New York City Experience (New York: John Wiley, 2000). ↩

-

Keller Easterling, Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space (London and New York: Verso, 2014), 15. ↩

-

Shannon Mattern, “Instrumental City: The View from New York’s Hudson Yards, circa 2019,” Places, April 2016, link. ↩

-

“Live, Shop, Work & Dine in New York,” Hudson Yards New York, link. ↩

-

Patrick J. Kiger, “Hudson Yards Rises above the Rails,” Urban Land, October 6, 2014, link. ↩

-

Kiger, “Hudson Yards Rises above the Rails.” ↩

-

Nick Stockton, “A Plan to Build Skyscrapers that Barely Touch the Ground,” Wired, March 24, 2014, link. ↩

-

“Hudson Yards to House Smartest Park in Town,” Hudson Yards New York, link. ↩

-

J. Michael Welton, “Hudson Yards: A Landscape for All the People,” the Huffington Post, July 23, 2013, link. Welton quotes Michael Samuelian, executive at Related Companies, as follows: “One thing that I’m most proud of is bringing nature back to Manhattan … to invite the birds, bees, and pollinators and clean the air—we’re bringing it back in a smart and innovative way.” ↩

-

“Open Spaces, A World to Discover,” Hudson Yards New York, link. ↩

Nicole Lambrou is an architect and PhD student in urban planning at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her research centers around the role of climate change in shaping design and policies.