On November 11, 2005, at 11 a.m., a convoy of eleven thousand trucks carrying eleven battalions of the Myanmar Army arrived in Yangon, Myanmar’s capital, from their bases on the outskirts of the city. Herding surprised bureaucrats from eleven civil agencies into trucks under the threat of arrest, these soldiers were helping Myanmar’s military government decamp to Naypyidaw, a newly constructed capital 320 kilometers to the north.1 Built without internationally known architects—in contrast to the international modernism of Brasilia or recent state complexes like Astana, Kazakhstan, which draw on star architects to legitimize these new capital cities—Naypyidaw’s arrival generated few headlines in the Western media beyond mild curiosity. Whereas the New York Times’ article on the relocation focused incredulously on rumored fears of Western invasion, local media lingered over the various astrological implications of the time and date of the junta’s move: a telling divergence in coverage.2

Reducing Naypyidaw to an architectural curio, however, overlooks the authoritarian logics directly expressed and exercised through the city’s planning and built form. A closer reading of the political, propagandistic, and religious urbanisms that form the basis of Naypyidaw—a form of political as much as architectural design—exposes a finely tuned projective apparatus of political will and authority. Together, these three vectors laminate to form the urban fabric of Naypyidaw, elucidating the junta’s political worldview and governing key aspects of its planning.

Security

Security issues play the most significant role in Naypyidaw’s founding, driving the essential parti of the city’s street grid and layout. Sprawling across 4,600 square kilometers (seventy-eight times the area of Manhattan), the city features wide, well-paved streets, and strictly delineated zones for hotels, residences, government offices, and military installations, as well as constant electricity.3 A rarity throughout the rest of the country to this day, the uninterrupted supply of electricity is the first indication that Naypyidaw is built from the mindset of a military operation rather than city planning.

Yangon, the former capital, was laid out by the British on a strict grid, with all of the north-south streets designed as one-way alleys regardless of their proximity to sensitive government offices or state buildings. North of downtown, a dense network of winding roads holds stately bungalows and low-rise apartment blocks of both pre–World War II and post-1948 independence construction, bounded by Yangon University on the shores of Inya Lake. Midcentury government offices proliferated in this central area, and they provided easy targets for demonstrations during the massive pro-democracy protests of 1988 led by Aung San Suu Kyi. Most protest leaders were enrolled at Yangon University, and the campus became the center of democratic activism. Downtown, protesters easily barricaded the narrow one-way streets, with the colonial British buildings that housed State facilities providing iconic backdrops for rallies. Even Myanmar’s holiest site—the Shwedagon Pagoda, located equidistant between downtown and the university—housed student-run “strike centers,” granting the uprising the implied support of the country’s powerful Buddhist monks.4

By 1990 the junta had subjugated the nascent revolution, vacating Myanmar’s first democratic election in decades and imprisoning revolutionary leaders. The memories of being “besieged” from within their own capital proved more difficult to dismiss. As a result of the turmoil, General Ne Win, Myanmar’s first dictator, resigned his formal role in the government. His successor, Senior General Than Shwe, the Burmese head of state from 1992 until 2011, was a longtime insider of Ne Win’s regime and had borne direct witness to the relative ease at which revolutionary groups had turned the urban fabric of Yangon against the military.5

As a result, Naypyidaw—designed and built under General Shwe—is a compartmentalized city, determined to hold the state at arm’s length from its citizens. The city is organized into six general areas: the ministry zone in the north, the hotel zone to the southeast, the diplomatic zone due south, the residential zone comprising two distinct neighborhoods in the west, the existing village of Pyinmana to the east, and the military zone further east on the city’s outskirts. Separated by kilometers of golf courses, lush jungle, and rice paddies, these enclaves appear less as a cohesive city and more as a series of figures on a blank map, sharing little spatial or cartographic relationship beyond the network of modern motorways suturing them together. The ministry zone houses the bulk of the civilian government edifices, and as such is the primary object of Naypyidaw’s urban security regime.

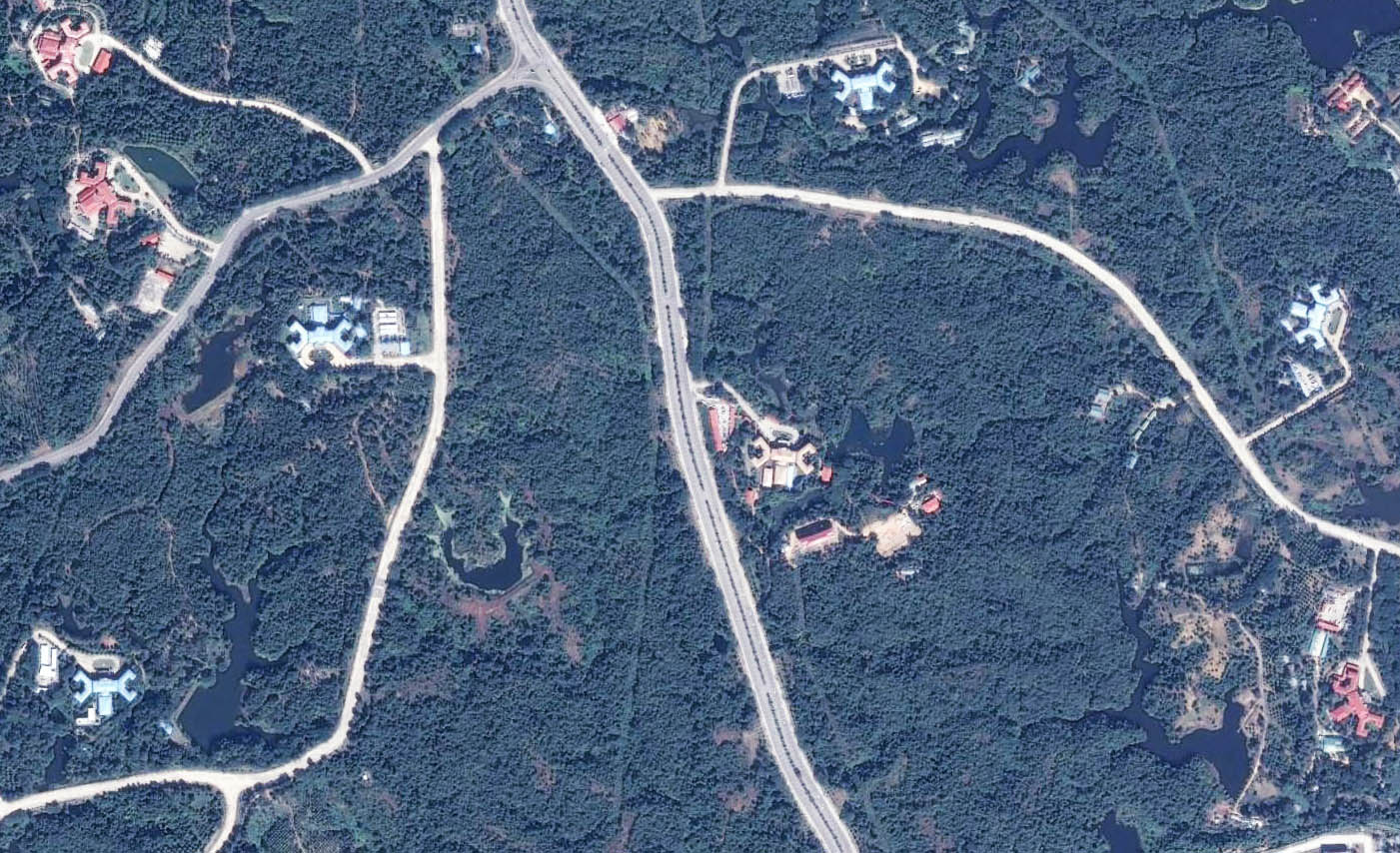

Bottom: Ministry of Health and Sports from above at center. Courtesy Google Earth, 2017.

The heart of Myanmar’s bureaucracy, which occupies the northern reaches of Naypyidaw, is akin to a suburban office park. Fifty-one identical two-story office buildings housing the staff of thirty-six ministries perched at the end of individual driveways branching from a six-lane highway that snakes through rolling hills covered in dense vegetation.6 Each ministry building shares the same floor plan—cruciform, with open rectangles turned on the bias at each end of the short arms. From the ground, they appear utilitarian, simple, and modern; from above, however, these open rectangles resemble scorpion claws, an animal said to bring power and good fortune in conquest.7

At the southern end of this main artery, the Union Parliament complex sits atop a raised platform separated from a monumental, twenty-lane thoroughfare by a dry moat. This largely deserted stretch of tarmac has become synonymous with Naypyidaw inasmuch as the city is mentioned in Western media—for example, the hosts of British motoring show Top Gear famously played a game of soccer on this roadway during their TV special tour of the country. Despite their apparent absurdity of excess, these barren stretches of asphalt are vital lines of defense against a second attempt at a 1988-style uprising.

Assuming protesters could mass in suitable numbers to block traffic on the freeway fronting Union Parliament, they would find themselves completely exposed to military interdiction from surrounding bases, with no cross streets to disperse through or private homes to hide in. Further, should this crowd continue north along the ministry zone’s single six-lane artery, narrow driveways and dense vegetation create choke points in the immediate proximity of the offices, whose monotonous repetition makes it difficult to assign symbolic meaning to places or buildings. The bureaucrats themselves reside in the residential zones some seven to eight kilometers away along even more of Naypyidaw’s oversize highways—a stark contrast to Yangon’s shop houses and apartment blocks, which were often directly adjacent to government facilities. Although religious motifs play a large part in the “myth” of Naypyidaw, no monument equal to Shwedagon exists within a ten-kilometer radius of the zone, avoiding the poor optics of evicting protesters from pagodas or temples.

The ministry zone shows the degree to which the junta considered Yangon’s urban heterogeneity as a dangerous liability to their continued control and undertook a concerted effort to remove the organs of state from possible domestic challengers.8 The entire city is designed to withstand a siege from within, assuming any and all Naypyidaw residents might be revolutionary agents. Naypyidaw defends itself against any local popular action not by “tanks and water cannons,” Siddharth Varadarajan wrote in 2007, “but by geometry and cartography.”9 By separating housing, religion, and foreign consulates from the state, Naypyidaw accomplishes a pre-emptive interdiction of the type of revolutionary covalence that was so effective in Yangon, divorcing possible sources of dissent and foreign support from the state and also from one another.

Propaganda

These security urbanisms can serve any government, whether military or civilian. Naypyidaw’s architecture, on the other hand, is innately linked with General Shwe’s own cult of personality. Literally translated, Naypyidaw means “abode of kings:” the overriding message of Myanmar’s capital is one of historical legitimacy, linking past and present governments into a single lineage of native Myanmar rulers.

The massive Defense Services Museum, thirty kilometers northeast of the ministry zone, places this legitimizing narrative on full display. Opened in March 2012, the museum’s collection is dedicated to the Tatmadaw (Royal Force), comprising Myanmar’s Army, Air Force, and Navy. Exhibitions are housed in nine massive pavilions arranged in a two-kilometer rectangle; a circular fountain so large it can only be run during VIP visits occupies the rectangle’s center. Navy and Air Force exhibitions are displayed in the two parallel arms of the museum, their collection of Soviet, British, American, and indigenous-designed aircraft and naval vessels spill out onto acres of tarmac. The Army exhibitions occupy the central bar linking the Navy and Air Force halls.

Upon entering the museum, immense portraits of Generals Shwe, Ne Win, and Aung San, three of modern Myanmar’s most crucial figures, greet the visitor. Ne Win, Shwe’s predecessor, overthrew U Nu’s civilian government in 1962, ruling the country until 1988. Aung San, Aung San Suu Kyi’s father, fought the British, and then the Japanese, for Myanmar’s (known then as Burma) independence, succeeding and founding the modern state in 1947. While the connection between Ne Win and Than Shwe is clear enough, the inclusion of Aung San is audacious, given his emancipatory goals. These portraits lay the groundwork for the style and substance of the exhibitions within—blunt and revisionist.

Exhibition rooms highlight singular aspects across the history of the Myanmar military (and by extension the kings and generals who led it) and their significant acts of conquest, defense, or insurrection. In the pre-colonial section, large paintings detail Burmese triumphs over neighboring Thai and Lao empires and Mongol incursions, replete with teakwood replicas of battle formations and military materiel. On the subject of British conquest, the museum instead highlights the few native victories over the Raj, glossing past the eventual fall of Mandalay in 1885. During WWII, the museum shifts almost entirely to Aung San’s efforts to first evict the British as a Japanese ally, and then his struggle against subsequent Japanese occupation as a guerrilla fighter—little mention is made of external aid he received to eventually repel the Japanese Army.

Historical linkages established, the remainder of the museum positions the Tatmadaw as the singular force for modernity in Myanmar. An elaborate parachute drop display, arranged prominently at the exit of the Army Wing, summarizes the junta’s case. By depicting the entire chain of command associated with parachute cloth production, spanning military hierarchies and several factories scattered throughout the country, it reminds viewers of the junta’s national reach. The contents of the drop show the breadth of the Tatmadaw’s industrial connections, which enable it to supply livestock, ammunition, and medical supplies wherever they are required. The military continues to occupy an outsized role in Myanmar’s economy, dominating technically oriented sectors like aerospace, construction, and agriculture, a product of decades of backing military-linked corporations that could be controlled by the state.10 Mounted above the airdrop, a photo collage shows similar supply operations undertaken by land, sea, and air: a clear message of the military’s logistical range and technical prowess. Such historical liberties are not unique to Naypyidaw. However, what is different in Naypyidaw’s case is the directness with which the museum’s national narrative escapes the exhibition halls and animates the architecture of the new capital.

History and Numerology

Theravada Buddhism provides the critical link between narrative and architecture. Myanmar is an overwhelmingly Buddhist nation, especially in the central lowlands stretching from Yangon (91 percent) to Mandalay (95 percent), the country’s two largest cities. On the whole, the population is estimated to be 88 percent Buddhist.11 Elements of animistic folk traditions (nat) have melded with Buddhism to form a pervasive spiritual-cultural mainstream, and belief in the supernatural and in a linkage between the cosmos and humanity is widespread.12

As the Tatmadaw recruits primarily from these central lowland regions, courtship of the nation’s monks is a necessity to avoid possible dissent in the military. Among the leadership, many generals and their families employ personal astrologers to plan important announcements or events for auspicious days.13 Public displays of piety or religious support, such as giving alms to monks or embarking on pilgrimages to holy sites, are sanctioned aspects of religious life in Myanmar. At the state level, this “merit making” or accrual of good karma is enacted at the scale of building by erecting pagodas or temples or restoring monuments in disrepair. 14 While these religious projects are generally open to the “public,” visitors and pilgrims alike, Naypyidaw’s pervasive security mechanisms and five-billion-dollar price tag (paid for with public money), are a far cry from typical precedents.15

Even by his colleagues’ standards, the former senior general and head of state Shwe was considered highly religious, comporting himself as Buddha or a king or both.16 When building his new city, he did not risk tempting fate: because he was told by his astrologers that Naypyidaw’s lucky number was eleven, the number pervaded the official relocation procession (eleven battalions, eleven thousand trucks, 11 a.m. on November 11, and so on). Shwe’s own lucky number is rumored to be six: thus, when told that remaining in Yangon any longer would surely lead to bloodshed, he and the senior leadership retreated to Naypyidaw ahead of the official column on the 6th of November (the eleventh month), at the astrologically prescribed time of 6:37 a.m.17

A New Paradise

In 2009, Than Shwe opened Naypyidaw’s Uppatasanti Pagoda, following a tradition of religious construction as a form of merit making. Uppatasanti was intended to surpass not only Than Shwe’s immediate predecessors—Ne Win and Prime Minister U Nu both constructed significant pagodas in Yangon—but ancient monarchs as well. Uppatasanti drew immediate comparison to Yangon’s Shwedagon Pagoda, the holiest site in the nation. An immaculate copy of the former on the exterior, Than Shwe’s pagoda tops out at ninety-nine meters (a lucky nine times eleven), about thirty centimeters shorter than Shwedagon. Uppatasanti is hollow inside, allowing pilgrims respite from Naypyidaw’s warmer climate. The interior and the combination of both Than Shwe and Naypyidaw’s lucky numbers in the height reveal a more personal significance. Paying an undisclosed sum to a Chinese monastery for a Buddha’s tooth to be housed in the pagoda, Than Shwe took direct aim at King Anawrahta, ruler of the first Burmese Empire to contain modern Myanmar’s borders. Supposedly, the tooth was a relic the king had tried and failed to obtain many times throughout his reign, now acquired eight hundred years later by the man who considered himself Anawrahta reincarnated.18 Large images of King Anawrahta and Buddhist scripture adorn the interior dome, to ensure the proper associations are made.

The associations with past royalty continue within the Union Parliament Complex. Burmese kings would often relocate their palaces after taking power, leading to a string of royal cities in Myanmar’s central plains, between the ancient power centers of Bagan and Mandalay. Taking the royal connections to heart, Than Shwe sited Naypyidaw on a location laden with pre-colonial significance, in the southwestern corner of this historical region of capitals. In more modern times, Pyinmana, the village engulfed by the new city, was General Aung San’s headquarters during his alliance with the Japanese during WWII. Furthermore, Uppatasanti Pagoda and arguably, the Union Parliament, fulfill ancient ceremonial roles as emblems of royal power.

Burmese kings traditionally announced their new capitals by constructing a palace and a pagoda—an act of concentrating both political and religious mandala (“influence”) and creating Jabudipa (“paradise on earth”). In so doing, the ruler announces himself as “World Conqueror and World Renouncer” (Cakkavattin and Bodhisattva).19 Uppatasanti Pagoda’s overt references to the achievements of King Anawrahta, and the relic he could not obtain within, reveal General Shwe’s intentions. Union Parliament’s many similarities to Mandalay’s Royal Palace (discussed below), although less overt than Uppatasanti, speak to a kind of palatial ambition. Taken together, Uppatasanti and the Union Parliament—pagoda and palace—illustrate Than Shwe’s attempts to unify his personal historicist allusions within the larger narrative of legitimacy at work throughout the rest of the city.20

Every building in the Union Parliament is built in the “syncretic” architectural style, which melds Modernist proportions and materials with traditional Myanmar architectural ornament and religious symbolism. Yangon’s City Hall (1934) and Central Railway Station (1954), both by Myanmar architect Sithu U Tin, are the apotheoses of this recombinant aesthetic.21 Unique against the colonial backdrop of the British administrative buildings concentrated in Yangon’s downtown, these buildings offered a glimpse of a new Myanmar that had extracted the benefits of British technology while keeping traditional cultural heuristics intact. Union Parliament’s syncretic blending of modern aesthetics and references to Mandalay’s Royal Palace announce the junta’s control of both modernity and antiquity as Myanmar’s natural rulers.

Sprawling across eight hundred acres and comprised of thirty-one buildings—an allusion to Buddhism’s thirty-one planes of existence—the Union Parliament borrows liberally from both syncretic precedents.22 Each two-story building features square floor plans, clad with double-height monumental columns above an ornamented plinth. In the case of the entrance hall, these columns are open to the elements as a portico (evoking Yangon’s City Hall), while in other buildings, the columns act as oversize mullions for sheets of glass windows. Concrete facsimiles of traditional teak screens from ancient Burmese palaces break the Modernist lines of the elevation, linking columns together with distinctive compound arches in the entrance hall. Bright splashes of pastel greens and reds against tan lend a festive, articulated appearance to the compound’s facades, highlighting the shared horizontal datum that unifies the complex. Above the columns, tiered roofs march upward in a stripped-down approximation of the four towers that punctuate the façade of Yangon’s Central Railway Station.

Bottom: Yangon’s City Hall. Photographs by the author, 2016.

Parliament’s tiered roof lines (pyatthat) link the complex to Mandalay’s Royal Palace. Traditionally, pyatthat symbolize the presence of a royal seat or an image of the Buddha. Stacked in groups of three to six, the higher the pyatthat, the more important the object beneath, allowing for an easy coding of a structure’s importance relative to its surroundings. The entrance hall and the two deliberating chambers flanking parliament have the tallest roofs and are therefore the most “royal” buildings in the compound. The Royal Palace holds several other similarities: a complex of buildings all of the same height to allow for roofline legibility, situated on an earthwork berm behind a moat, and oriented with the main entrance facing east, the source of life.23 As with the scorpion-shaped ministries, the deliberate fusion of nostalgia and technology positions the junta as once and future rulers of Myanmar.

Symbol or System

Naypyidaw was clearly meant to function as a governing enclave first and foremost— albeit “function” in a more security and propaganda-oriented sense as opposed to a bureaucratic one. One might be tempted to dismiss Naypyidaw as a one-off event, a product of Myanmar’s isolation under military rule. However, contemporaneous developments elsewhere in the world indicate otherwise. Naypyidaw could be understood as a “mediatic” city. That is to say, a city giving significant weight to not simply the efficient housing of its citizens but also the efficient housing of a specific cultural message. In this reading, Naypyidaw’s calibrated narrative-producing agenda certainly places it on par with Doha, Sharjah, Dubai, or Baku. However, what separates Naypyidaw from these cities is the degree to which it was created without Western-derived visual cues. In the absence of a Frank Gehry, Jean Nouvel, or an OMA to translate the junta’s propagandistic agenda into a formal language more familiar to Western observers, Naypyidaw has flown under the radar of Western media.

The fact that Naypyidaw was built at all, and its fidelity to its core narrative expressed throughout the built environment, is perhaps the most lasting testament to the junta’s abilities at the height of its power. Naypyidaw is an intricate yet overpowering urban mechanism, balancing security, religion, and nationalist narrative at an immense scale. On these terms alone Naypyidaw is certainly worthy of architectural attention and analysis, yet further investigation beyond the novelty of the city’s sudden debut reveals a dense web of narrative and security parameters working in tandem to produce an authoritarian ecosystem. Than Shwe managed to simultaneously reimagine the capital city as both a secure bunker and a billboard, united in the synergy of security, religion, and propaganda. Today, Naypyidaw’s role in Aung San Suu Kyi’s civilian governments remains to be seen. Quoted in 2012, former Vice Admiral Soe Thane said, “military governments were thinking about security; politicians are for the people.”24 The city’s greatest test will be whether time blunts its propaganda or breaks down barriers between bureaucratic and domestic zones as Myanmar transitions to democracy under civilian rule.

-

Aung Zaw, “Moving Target,” Irrawaddy, November 9, 2005. ↩

-

“Myanmar’s New Capitol; Remote, Lavish, and Off-Limits,” New York Times, June 23, 2008, link. ↩

-

Veronica Pedrosa, “Myanmar’s ‘Seat of Kings,’” Al Jazeera, November 20, 2006. ↩

-

Dulyapak Preecharushh, Naypyidaw: The New Capital of Burma (Bangkok: White Lotus Press, 2009), 52–54, 135. ↩

-

Maung Myoe, “The Road to Naypyidaw: Making Sense of the Myanmar Government’s Decision to Move Its Capital,” Asia Research Institute Working Paper Series, no. 79 (November 2006), 9. ↩

-

Ei Ei Toe Lwin, “NLD to Slash Ministries in Proposed Shakeup,” Myanmar Times, March 17, 2016. ↩

-

Myoe, “The Road to Naypyidaw,” 14. ↩

-

Vadim Rossman, Capital Cities: Varieties and Patterns of Development and Relocation (London: Routledge, 2017), 108. ↩

-

Siddharth Varadarajan, “Dictatorship by Cartography, Geometry,” Himal South Asian, February 2007. ↩

-

David I. Steinberg, Burma: The State of Myanmar (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press: 2001), 69. ↩

-

“The Union Report: Religion,” 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census, vol. 2 (Naypyitaw: Ministry of Immigration and Population, May 2015), 3. ↩

-

Stephen McCarthy, “Losing My Religion? Protest and Political Legitimacy in Burma,” Griffith Asia Institute Regional Outlook Paper, no. 18 (2008), 3. Also see, Myoe, 10. ↩

-

Preecharushh, Naypyidaw: The New Capital of Burma, 94. ↩

-

McCarthy, “Losing my Religion,” 4. ↩

-

“Myanmar’s New Capitol; Remote, Lavish, and Off-Limits,” link. ↩

-

Aung Zaw, “The Dictators Part 10: Than Shwe Enjoys Absolute Power,” Irrawaddy, May 10, 2013. ↩

-

Zaw, “Moving Target.” ↩

-

Simon Roughneen, “Naypyidaw’s Synthetic Shwedagon Shimmers, but in Solitude,” Irrawaddy, November 13, 2013. ↩

-

Myoe, “The Road to Naypyidaw,” 14. ↩

-

Myoe, “The Road to Naypyidaw,” 14. ↩

-

John Falconer, et al. Burmese Design & Architecture (Singapore: Periplus Editions, 2000), 166. ↩

-

David I. Steinberg, “The Magic in Naypyitaw’s [sic] Numbers,” Nikkei Review , March 9, 2017. ↩

-

Falconer, Burmese Design & Architecture, 168. ↩

-

David Pilling, “Naypyidaw: A General’s Fantasy Becomes Real,” Financial Times, November 27, 2012. ↩

Galen Pardee is a designer, educator, and researcher based in New York City. His research focuses on the representations of culture, authority, and character in the built environment and the technical, architectural, and material processes endemic to these translations.