In 1543, Andrea Palladio was tasked with designing Cardinal Niccolò Ridolfi’s entrance to the city of Vicenza. Palladio erected a series of temporal structures for the occasion, laying out a series of classical typologies of monument (an obelisk, a triumphal arch, etc.) to mark the route of the cardinal’s procession toward the cathedral. This sequence of forms, in the words of Pier Vittorio Aureli,

symbolized the veritable analogous Roman city generated by this circuit; Palladio considered them to be ideal and instant devices for urban reinvention, radically transforming the Gothic form of the city into a classical landscape. The theme of the triumphal procession also highlights the city as a contested field of directions to be mapped and manipulated by a series of punctual interventions.1

What enabled Palladio to realize these simple yet precise gestures was his profound knowledge of classical architecture. Palladio developed a unique but flexible methodology based on his research and its application to the specificity of each site, resulting in solutions with breathtaking (and apparent) simplicity—a mode of working, sometimes minimal production following in-depth research, comparable to the practice of many contemporary artists.

Such creative engagement with the past, whether in the guise of idealization or total rejection, has always been one of the central concerns of art since it became a discipline independent of craft. Dialogues with history have sometimes resulted in stifling academicism but have also brought about tactics for breaking the limits imposed by the dominant discourse of the present. There have been periods in the history of both art and architecture when the latter case coincided with a fundamental transformation of society and economy, compelling artists and intellectuals to use historical precedents as a material to imagine new forms of politics and aesthetics in place of current ones no longer fit for purpose—the Italian Renaissance serving as one prominent example, within the Western canon. Facing the emergence of capitalism, political instability, and the Reformation, artists appropriated the visual language of antiquity, which emerged from an entirely different political system from their own, and fashioned a radically new aesthetic code that was both specific to their contemporary context and envisaged the social order yet to come.2 One of the culminations of this process was the works of Palladio, whose design, built upon his unrivaled research, defined civic architecture for hundreds of years. Manfredo Tafuri wrote that for Palladio, “the classical code was merely a field of variations, and not a handbook of rules.”3

In the same way, the “field of variations” offered by history is where the artist Martin Beck operates and suggests one way of reading his two-year-long project for the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts (CCVA), which is now brought together as a book. Concisely titled Program, Beck’s project for the Carpenter Center has a simple origin but resulted in a highly complex and multifaceted outcome. Initially, James Voorhies, then newly appointed CCVA director, asked Beck to design a coffee bar for the center’s foyer area—part of a larger intention to activate and revitalize the institution’s public spaces. The coffee bar never materialized, but the conversation between Beck and Voorhies evolved into a two-year-long endeavor that examined every aspect of the museum’s machinery through “a series of punctual interventions,” compelling Beck to dive into the depths of the Carpenter Center’s institutional memory.

An art institution is the sum of many things besides art—its physical shell, its finances, its internal and external sociopolitical dynamics, its relationship with a hosting organization (whether state, private foundation, or university), its educational and academic missions, and the quality of its program, itself determined by the agendas of the curators and directors, budget, and changing trends. An institution is defined by the complex interaction of these numerous and ever-shifting elements, meaning that external or internal events that seemingly have no aesthetic significance can dramatically alter the character of the institution.

Architecture’s role in this is both small (as one of many elements) and crucial (it constitutes the most visible part of the institution, as well as providing the space for everything else to take place). Architecture, like most things, is ideological. And the ideology behind the Carpenter Center feels utterly alien to us today; it was in fact already old-fashioned at the time of its construction in 1963. In the interview with Alex Kitnick included in the book, Beck puts it like this:

It was started as a Bauhaus-type school that opened decades too late. It was housed in a building that had been iconic from the get-go—students couldn’t really touch it or do anything with it. And it was supposed be a remedy for Harvard’s anxiety about a visual world that was becoming increasingly complex… And here we are in the early ’60s, at Harvard, putting something together that relives the modernist dream of the 1920s. They think Bauhaus. They hire Le Corbusier. Against the backdrop of the 1960s, that combination produces a peculiar out-of-timeness. I think that is what attracted me.4

How, then, might an institution that is housed in a building whose underlying ideology is now incomprehensible to us negotiate a new self-understanding through its own more recent history? And how should its physical space be interpreted now?

Beck’s Program explores these questions through a deep but also unsentimental engagement with modernist legacy—an artistic strategy that is widely deployed and discussed and yet rarely analyzed with much historical perspective. And this is where a comparison with Palladio might become relevant. If we accept T. J. Clark’s dictum that “modernism is our antiquity,” one might also view Renaissance Italy as a historical precedence for today’s practitioners—the beliefs that fueled modernism are as distant to us as antiquity was to pre-modern western artists, even though there are surely no artists who are not informed to some degree by one or more forms of modernism.5

Because modernism was so diverse and its methodologies and variations so numerous, contemporary practitioners have almost endless material to devise a new visual language by combining, modifying, adding, and subtracting from the aesthetic arsenal built by modernism.6 On the other hand, this state of affairs requires artists to possess profound historical knowledge, a strong grasp of political economy (past and present), highly developed personal principles, and the ability to adapt and improvise in response to a specific context. The tool kit available to practitioners today is so rich that only those with the most advanced ability and intellect can fully utilize it. In this condition, it is useful to reexamine the Renaissance ideal that demanded intelligence and broad historical knowledge from the artists.

It is on these grounds that one might compare Martin Beck to a figure like Palladio, for his practice is rooted in extensive and distinctive study of history, architecture, art, popular culture, and society. For Beck, one could say that artistic research is worthless unless it enriches the field of scholarship within which his research is being conducted, and further, that research is incomplete unless it is transformed into an aesthetic form that has visual value on its own.7 In other words, Beck does not confuse the quality of research with the artistic quality.

Each display, intervention, event, and newly produced artifact from Beck’s Program was called an “episode” and numbered chronologically. The first episode, titled Removed and Applied, responds explicitly to the architectural context of the Carpenter Center. In the original design by Le Corbusier, the gallery on Level 3 of the building was a 3,900-square-foot space with an open plan. However, in 2000, an enclosed white cube was built within the original gallery, undoing the intended open plan. The exterior of this box-within-gallery, designed by Peter Rose + Partners, was clad in dark steel panels. In October 2014, Beck replaced these steel panels with gypsum boards that were then primed, sanded, and painted in white. The resulting surface is not only better integrated into the original architecture but also increased usable wall surface for the museum. At first glance, the intervention is reminiscent of Michael Asher, whose influence Beck acknowledges.8 However, their significant differences become immediately apparent. While Asher’s interventions were aimed at exposing institutional mechanisms and disrupting institutional power, Beck enhanced the functionality of an institutional space, thereby embedding himself in its structure. At the same time, Beck critiqued the museum’s desire to own a signature artist’s intervention. Since the 1990s, museums have commissioned artists to redesign the public areas of the institution such as the foyer or café, and these interventions are almost always realized in a style immediately recognizable as that of the artist.9 Being seamlessly blended with the museum’s architecture, Beck’s episode flatly refused to give the museum a visible artist’s signature. In effect, the episode acted as a double critique of both the artist’s role as a “content provider” in the form of decoration-as-art and of the classic institutional critique where an artist legitimizes an institution by facilitating its auto-critique. Beck’s position, in which he inserted his work into an institution yet denied it, is ambiguous and thereby does not allow an easy categorization.10

For the second episode, Beck reproduced the Carpenter Center’s inaugural press release from 1963 and distributed it both through the center’s mailing list and as a takeaway from a dispenser on the altered wall in the first episode. For the third episode, Beck compiled photographs from Harvard’s archive and distributed them as a digital slide show via CCVA’s website. These two simple gestures at once signaled the depth of institutional memory Beck was prepared to dive into as well as his further entrenchment into the institutional structure as he co-opted its two most used communication channels.

The fourth episode, titled A Report of the Committee, was comprised of three elements. The first was an installation photograph of a 1971 exhibition at the Carpenter Center called The Art of Maya Hieroglyphic Writing, which Beck distributed digitally. In this photograph, one can see a black floor-to-ceiling curtain that was often used in the early years of the center to divide Le Corbusier’s open plan. For this episode, Beck instead designed a floor-to-ceiling curtain in cream-pink silk chiffon. In the context of the museum, this elegant and unassuming object is highly indefinite. Being translucent, it did not block sunlight like the black curtain in the photograph or the adhesive dark film that is more commonly used today. While it subtly altered the atmosphere, one might not have known why it was there unless they were aware it was an artwork. As in the first episode, Beck avoided the recognizability generally expected of artistic interventions. The ambiguity of the curtain created a stark contrast to the sense of confidence emitted by the third element of the episode, which was a five-page report written in 1960 by a committee appointed to shape the burgeoning visual arts program at Harvard. Presented in a vitrine near the curtain, this document was suffused with the optimism and self-assurance typical of such a text. These three elements together mirror the three core components of the Carpenter Center—pedagogy, exhibition, and architecture, all of which were filtered through Beck’s subtle artistry.

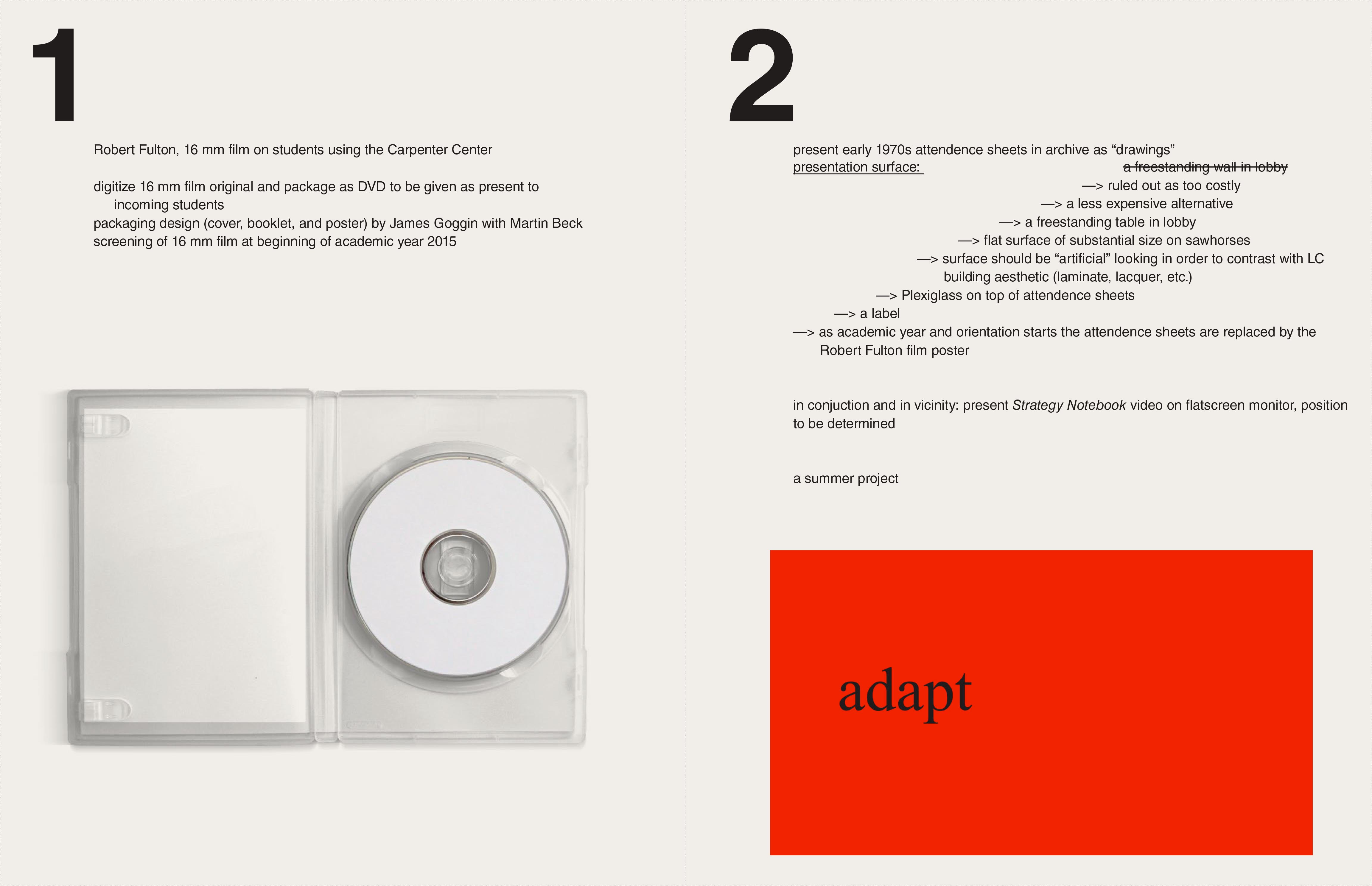

Beck continued his dissection of the Carpenter Center’s institutional anatomy in episodes five and six. Episode five addressed the issue of visitor attendance, essential yet arguably the least artistic aspect of a museum. Beck took three attendance sheets, notebook pages with hash marks denoting the visitors, from the 1970s. These three sheets of paper, which resembled abstract drawings, testify to the beginning of the data-driven management of museums. The document was displayed on the left half of a large, white-laminated display system. Measuring 120 by 60 inches with the height of the display surface at 32 inches, this object was in the words of the artist, “neither a table for seated visitors nor a typical viewing surface for standing viewers, something in-between.”11 The right half of this large structure was mysteriously left empty. Installed in July 2015, this episode took place during the summer break of Harvard (attendance sheets exhibited during the least attended time of the year). Upon the return of the students in September 2015, Beck completed this episode by placing a poster announcing the next episode on the right side that was hitherto left empty.

Episode six, announced in the poster, was a film screening. Beck unearthed a 16mm film titled “Reality’s Invisible” from 1971 by the experimental filmmaker Robert Fulton from the Harvard Film Archive. In this film, Fulton, who was teaching at the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies at Harvard, portrayed the life of students and faculty at the Carpenter Center. This film was screened in September 2015 at the opening reception of the 2015–16 VES Visiting Faculty exhibition, an event that inaugurates the new academic year and welcomes returning students and faculty. Furthermore, a DVD of the film was given as a gift to students of VES and Film and Visual Studies. In this episode, Beck shifted his focus onto the Carpenter Center as a museum attached to a prestigious educational institution and the rituals such an arrangement naturally produces.

The next episode directly addressed the design language of Le Corbusier. Titled The Limit of a Function, the seventh episode was a table/vitrine made of powder-coated steel and plywood that is still used in the Carpenter Center. Its measurement was derived from the grid pattern Le Corbusier incised in the concrete floor of Level 3. It has two rectangular recesses covered by glass that function as vitrines, while the remaining plywood surface functions as a table. Its legs have casters that allow it to move around easily, and it is accompanied by two benches and several stools made of the same material. In effect, Beck replicated a section of the gallery floor as a floating surface with new functions. As with episodes one and four, Beck presents a highly ambiguous suite of objects. On the one hand, the piece is a singular and elegant sculpture with a function. On the other, its aesthetic and proportion allow it to blend into the surroundings to the point that it frustrates the expectation of unique identity for an artwork. In the interview with Kitnick, the artist discusses this ambiguous invisibility:

Most of what I did was ephemeral…and there is no object trail to the project. Looking at it now, after two-year engagement, one could say the project inserted itself into the Carpenter Center like a ghost—there in spirit but absent as a body.12

And later in the same interview:

That creates a tension in the institution, as the project was always there and not—at the same time. People were talking about it very concretely while simultaneously wondering where or when it would happen. It’s a bit of a paradox that might never get resolved, but so is the Carpenter Center.13

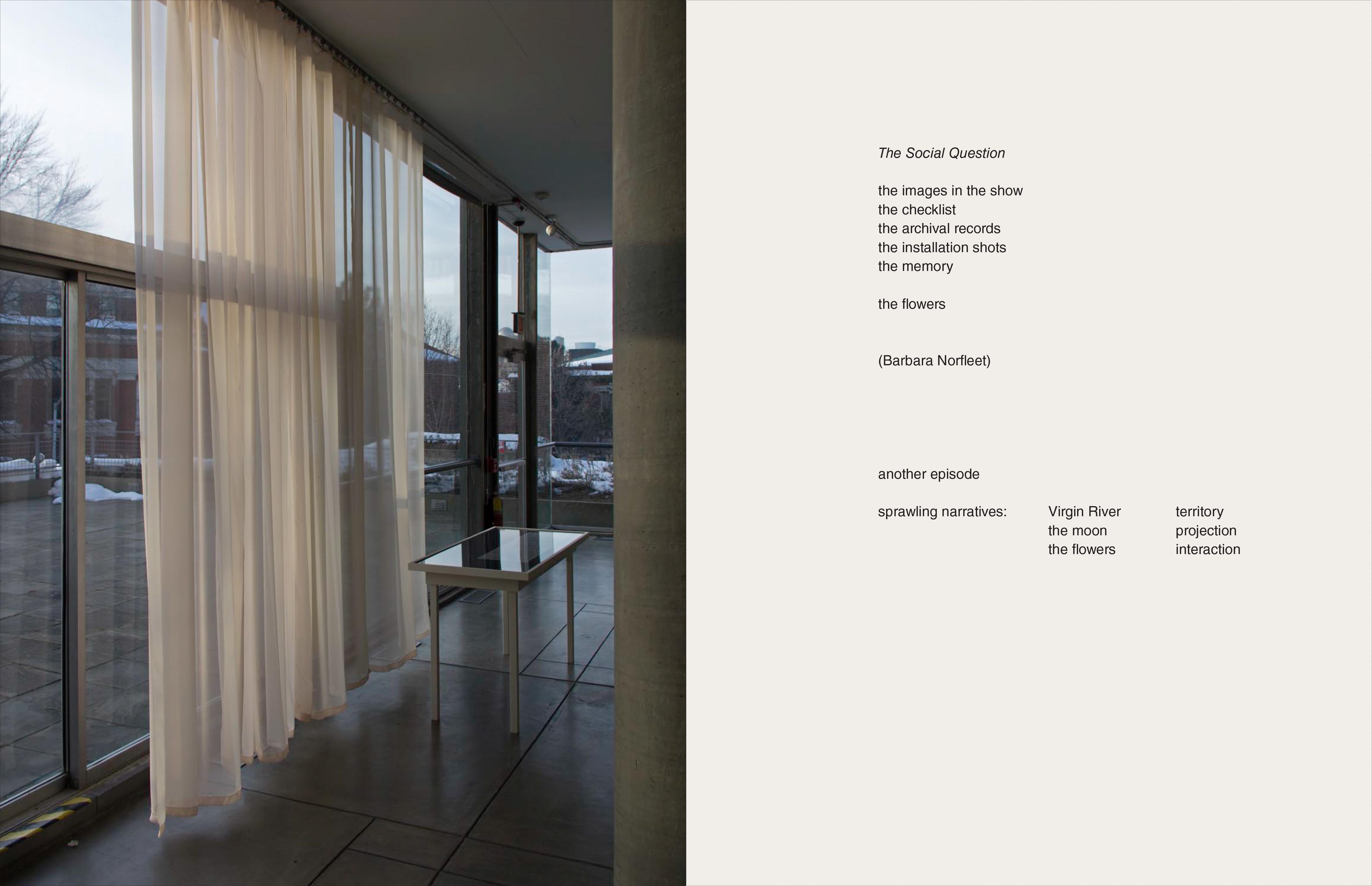

For episode eight, Beck engaged with a 1973 exhibition at the Carpenter Center called “The Social Question: A Photographic Record 1895–1910” curated by Barbara Norfleet and William S. Johnson, addressing the question of exhibition design.14 The original exhibition presented a selection of photographs from the collection of the scholar and activist Francis Greenwood Peabody, who founded the Social Ethics Department at Harvard in 1906. Beck examined the documentation photographs of the exhibition—which were unusual in that they focused primarily on the visiting audience—to produce an interpretation of the original exhibition design and a new space to present the documentation photographs. The pictures also captured the ubiquitous presence of flower arrangements in the original exhibition. Beck’s display also included several vases with lush flowers.

The flower is an important detail that points to the least discussed aspect of Beck’s practice, namely his fascination with the sensuous. Because of his rigorous research and extremely reduced and concise visual language, Beck is often mistaken for being solely analytical and theoretical—an artist whose output is exclusively intellectual. However, Beck’s oeuvre demonstrates his remarkable ability to strike a balance between the systematic mode of thinking informed by modernism and the sharp sensibility for beauty and emotion. The flower detail of this episode reveals the way in which Beck uses sensuous objects to disrupt and complicate the otherwise strict geometry of the display system.

The penultimate episode examined the form of artist lecture. In a talk titled “An Organized System of Instructions,” Beck examined the role of public lecture as a communication tool, both for the artist and the institution. At the same time, he discussed the specific historical, social, and architectural context that the Carpenter Center offered to him and the meaning of working in that particular institutional setup. Beck’s lecture was a collage of historical texts on communication systems such as Rudolf Arnheim’s “Visual Thinking” from 1969, architecture theory, texts from the center’s archive, emails and other correspondences from the preparation period of Beck’s project, and new text he wrote for this occasion. The lecture transcript, which is included in the publication (a video recording is also available on CCVA’s website, once again defies the common expectations of an artist’s talk—that it will provide a general overview of his/her practice (preferably with a slide show) and be unmistakably performative—and offers a far richer and complex image of what it means to operate as an artist. Beck discusses how to think through a museum, and the principles that mark his thought process, the format of the lecture itself, and the history of presentations. In spite of the academic or practical origin of the fragmented text, the lecture was poetic; it produced meaning not only through logical argument but also through associations among the fragments. The mixture of theoretical and deeply personal texts rendered it at once calm and emotional. In it, Beck discusses the inherent uncertainty of the format of artist talk:

Preparing this talk, I kept wondering if what is said at an artist talk only fulfills a supplementary function of the format. Speaking about art and explaining its intentions and meaning can certainly produce insights and allow for a deeper understanding. But since we’ve heard that “clear speaking” is supposedly “obsolete thinking” and that “clear statement is the afterlife of the process which called [an artwork] into being,” I am thinking about the role this talk plays in my overall project… The benefits of being there and the challenges of not being there. Presence and absence.15

In the tenth and final episode of Program, Beck engaged with the exhibition format as the nexus of the Carpenter Center’s educational, historical, and aesthetic missions. He took a 1966 exhibition at the center called “Fifty Photographs at Harvard, 1844–1966” as a case study, which showed images from the Carpenter Center’s photography collection that was originally amassed by Davis Pratt and later dispersed and partially transferred to the Fogg Art Museum and other Harvard collections. The show also included photographs by students from the Carpenter Center’s Visual Studies program from the 1960s. While many of the photographs from the 1966 show were lost, Beck gathered what remained of them from the Fogg Art Museum collection as well as archival documents about the pedagogical function of photography and displayed them in an exhibition titled Fifty Photographs in summer 2016. While episode eight focused on the display system as a mechanism of presentation, episode ten emphasized the exhibited artworks themselves. As the preceding nine episodes dissected and reconfigured every aspect of the institutional framework, episode ten concluded Program by highlighting the objects that fill that frame, thereby completing the complex picture that is an art museum.

Upon reading An Organized System of Instructions and moving through Program, one realizes that the project is nothing short of a radical rethinking of the discipline of exhibition making. For an institutional solo show, it is not uncommon to have a two-year production period followed by a well-publicized opening of the exhibition. Beck displaced this long-established order and proposed a more elusive arrangement. He conflated the production and exhibition periods, effectively using the institution both as the site and the material to produce and exhibit works over a two-year period. Indeed, the individually understated ten episodes/pieces would constitute a substantial but not unusually large solo show if considered that way.

Beck even used the book as an exhibition space to assemble the works, and the design of the book itself testifies to this unique process. Designed by James Goggin through an extensive dialogue with Beck (who is an accomplished graphic designer), the layout constantly modulates the density of content throughout the book, creating a remarkably spatial experience when leafing through its pages. Its design is in fact akin to the experience of walking through one of Beck’s exhibitions. The images and texts are arranged to create smooth flow and surprising encounters. The layout never feels random or disorderly. Every element appears to be exactly in the right place.

Beck summarized the project in his lecture:

Although self-contained and nonsequential, the individual episodes connect the institution’s sites of public interface: the press release, the physical space, the exhibition, the educational mission, students and visitor relations, artist talks, and a collection. They focus on the institution’s interactions with its various publics and how, in the process, it constitutes itself as an amalgam of education, presentation, and conversation.16

But what is the significance of Beck’s Program now that the process is completed? How does it resonate among us now and in the future? Beck described the project as a ghost residing in the Carpenter Center. But what is the afterlife of that ghost?

In order to answer these questions, one must understand a central concern of Beck’s artistic practice—that even though he produces objects and images with exceptional aesthetic quality, his true medium is exhibition making. It is the totality, the configuration of artifacts, the social context, the supplementary materials like a press release, and the architecture of the venue that together constitute the art exhibition and the work of art that Beck produces. It is a spatial and social composition. An exhibition, however, is temporal by definition. Though the individual elements may continue to exist, their configuration in time and space cannot be repeated. So what remains from Beck’s exhibition-as-artwork? The answer is the principle for exhibition making. When one enters an exhibition by Beck, one is struck by the impeccable precision with which he uses and articulates the given space, and the highest degree of discipline and control required to achieve that level of precision. An exhibition by Beck becomes a new standard by which to judge every subsequent exhibition in the same space. Of course, the venue may choose to ignore such a standard, but it nonetheless enters the institution’s unconscious—the institution will never entirely be able to repress the inadequacy it may feel when its exhibitions fail to achieve the same concision set by Beck. Because Beck offers a methodology for how an exhibition could be mounted, and because he is an artist without a fixed medium in a conventional sense, his principle may be applied to any exhibition with any medium. Perhaps not an instruction on how to do things, but a general principle that governs an approach toward exhibition making.

And it is this aspect of his practice, that his ultimate output is a principle, that makes a comparison with Palladio most pertinent. Though he had many built works, it was ultimately the architectural principle he offered in “I quattro libri dell’architettura”—highly abstracted and systematic yet flexible enough to be adopted in various contexts— that made Palladio the most influential architect in the West before modernism.

Similarly, Beck’s principle of exhibition making is not a rigid system but a flexible attitude and methodology for engaging with space and objects and imagining how they could come together and remain active. In the essay included in the book, Keller Easterling writes:

You look at it from the side, like a dog, and try to do one or two things that set up potentials between the parts or start a chain reaction. You probably won’t offer a fixed instruction for how it will always look. There are architects for that kind of tedium. You can only give an instruction for what the space might be doing—for some event that might cue another event in an unfolding series. You can’t orchestrate a balanced homeostasis, but you can prompt an interplay that keeps things productively imbalanced.17

In the Carpenter Center project, Beck supplanted the spatial composition of objects with an arrangement of works through time and transferred the function of space to the book. By adapting to this unique format, every element that constitutes the Carpenter Center as an institution has undergone artistic rearrangement, all absorbed into the potential aesthetic field. The book communicates not only what Beck did at the Carpenter Center but, more importantly, how he made decisions and how he worked through them. Beck marked each important spot on the map of the institution, and the marks continue to affect the museum. These marks are the afterlife of the ghost that was Program.

-

Pier Vittorio Aureli, The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011), 51–52. ↩

-

I am using the word “artist” in an expanded sense that includes practitioners of both fine and applied art. ↩

-

Manfredo Tafuri, Venice and the Renaissance (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995), 127. ↩

-

Martin Beck, An Organized System of Instructions (Cambridge, MA, and Berlin: Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts and Sternberg Press, 2017), 126, 133. ↩

-

“Already the modernist past is a ruin, the logic of whose architecture we do not remotely grasp…because the ‘modernity’ which modernism prophesied has finally arrived that the forms of representation it originally gave rise to are now unreadable… Modernism is unintelligible now because it had truck with a modernity not yet fully in place.” Clark’s usage of “modernity” roughly means “capitalism,” while “a modernity not yet fully in place” refers to possible modernities without capitalism, which are now unimaginable. T. J. Clark, Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999), 2–3. ↩

-

Serious historicization of non-western modernism is still in its early stage, and even an ambitious exhibition like Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965 at Haus der Kunst in Munich (October 14, 2016 through March 26, 2017) can only serve as an introduction to this vast legacy. ↩

-

For instance, his book The Aspen Complex (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012) brought together for the first-time research on the 1970 International Design Conference in Aspen as well as on MIT Architecture Machine Group’s the Aspen Movie Map as a dedicated publication. ↩

-

For instance, Untitled from 1988 in which Asher extended the height of the gallery walls at Artists Space in New York. Voorhies discusses this project in his essay in relation to Beck’s works. James Voorhies, “Functioning Limits,” in Beck, An Organized System of Instructions, 26–27. ↩

-

These artists include Jorge Pardo, Liam Gillick, Tobias Rehberger, more recently Céline Condorelli, and many more. ↩

-

Nor did institutional press know how to respond to such an ambiguity that does not resemble anything that they expect from an artist. Regarding the whole of Program and not only this episode, Beck told Kitnick, “Indeed, The Harvard Crimson did not report on it. I think most of the press didn’t know what to do with the project, as there was no splash, no single event, no ‘this-is-it’ moment.” Beck, An Organized System of Instructions, 134. ↩

-

Beck, An Organized System of Instructions, 99. ↩

-

Beck, An Organized System of Instructions, 125. ↩

-

Beck, An Organized System of Instructions, 138. ↩

-

Not only has Beck produced works on the subject of exhibition design, but he has also designed many important exhibitions, both on his own and in collaboration with Julie Ault, at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (Montreal); Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig (Vienna); and other institutions. ↩

-

Beck, An Organized System of Instructions, 180. ↩

-

Beck, An Organized System of Instructions, 188. ↩

-

Keller Easterling, “Seven Contemplations on Program,” in Martin Beck, An Organized System of Instructions, 62. ↩

Yuki Higashino is an artist based in Vienna.