In the United States, the gun industry—investors, manufacturers, distributors, lobbyists, and their paid representatives in Congress—has made it difficult to discuss gun violence for what it is: a public health crisis of the highest proportions.1 Those who stand to gain the most politically and financially from its obfuscation leverage the forces of poverty, gender-based discrimination, ableism, and racism in order to deflect public attention from the easily regulated tool at the center of the maelstrom. They disconnect perpetrators of domestic violence from their deadliest weapons, they ask consumers to pretend that means don’t matter when it comes to suicide, and they insist that the correlation of gun violence with areas of poverty has everything to do with individual responsibility and nothing to do with structural disinvestment. With their sallying forth of the tried-and-true trope of US exceptionalism, we are asked to accept that daily mass shootings are simply the cost of freedom in a Second Amendment society. But no exceptions can be made. The conditions for life and death should not be up for partisan debate.

Nonetheless, raising the question of gun control in this country tends to elicit hysterical cries of politicization, irrational fears of government seizure, or accusations of liberal dog-whistling, instead of thoughtful conversation about what might reasonably be done to address the crisis.2 The most recent issue of CLOG has waded into this environment, admirably working to dodge all of the jerking knees to put their now practiced editorial mantra of “slowing things down” to use, nominally in the service of a more considered debate. Since its founding in 2011, CLOG has tackled topics as wide-ranging as “BIG,” “Sci-Fi,” “Miami,” and “Prisons”—mapping out a terrain for its subscribers that productively connects the trendy to the thorny through a perspective that has grown to include topics that are not exclusive to design or architecture (though it never strays too far away from those fields’ interests).3 The bite-size pieces, assembled via open call, intend to pepper readers with a variety of viewpoints—in the voices of historians, designers, advocates, and technicians—that will leave them with a more informed foundation from which to assess the topic at hand on their own.4 Unfortunately, given today’s equally a-la-carte political milieu, with “GUNS” the editors have chosen a topic whose urgencies demand precisely the type of clarity that their format is designed to work against. This noise needs to be cut through, not curated.

Moving page by page between the issue’s one hundred individual pieces, which range from data visualizations to mini histories to interviews, readers will encounter many worthwhile contributions. A number of graphs and charts show the truly extraordinary material presence that guns have in the United States,5 the increasing frequency and lethality of mass shootings in this country,6 the disturbing correlation between mass shootings and gun companies’ rising stock prices,7 the demographic profile of the average mass shooter (hint: young, white, male),8 and the short attention span the country seems to have when it comes to analyzing such events.9 Editor Jacob Reidel’s autobiographical sketch of the tedious yet easily manageable process required to obtain a rifle license in New York City is both sensitively and informatively narrated.10 The dramatic irony of African American hip-hop artists being doubly targeted by gun culture—first in the flesh by the disproportionate effects of gun violence experienced by communities of color, and second in court for the depictions of guns in their lyrics—is eloquently described by Carrie Smith.11 To name only a few.

But, paradoxically, the editors’ attempt at a certain kind of straightforwardness is consistently undermined by their effort to maintain a semblance of impartiality, to “consider the complexity of various perspectives” as they say in their all-too-brief editorial.12 Manufacturers, shooting range owners, technicians, and video-game designers, among many others, are given an outsize proportion of the issue’s real estate, without pointed rebuttal.13 The relationships between race,14 gender,15 class,16 and gun violence aren’t given adequate prominence. Nor are the hideous legal tactics17 and current legislative priorities18 of the gun lobby.

That being said, a simple rebalancing of the contributions wouldn’t suffice. In her essay on the difficulties faced by museums of gun culture in the United States, Ashley Hlebinsky, the Robert W. Woodruff Curator of the Cody Firearms Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, laments the “awkward position” for gun museums when it comes to bridging the gap between guns as art objects and guns as historical actors.19 The tenor of the issue speaks to this anxiety, pleading with its readers to give guns the thoughtfulness they—apparently reflexively—deserve as designed objects. The attention paid to guns’ efficiency, flexibility, and history elicits something akin to admiration. And here design certainly gets the job done—ruthlessly, and to great effect. Thus, having facilitated an informed takeaway along these lines, the editors are seemingly satisfied that they’ve short-circuited today’s more typically reactionary rhythms of political discourse.

But together with its objects, design is inseparable from culture, and the editors fail to adequately acknowledge that gun culture is not only the (partial) object of the issue’s study but also the context for its reception. And in this culture’s court of public opinion, there’s no doubt that architecture has standing. It is certainly an actor, as the spatial confines of gun violence have direct effects on the violence itself.20 And architecture is a symbol as well, representing particular histories, populations, and ideologies at the expense of others. Underlining this fact, and laying the groundwork for an impassioned response that has yet to come, two of the far right’s most outspoken institutions recently made this standing explicit.

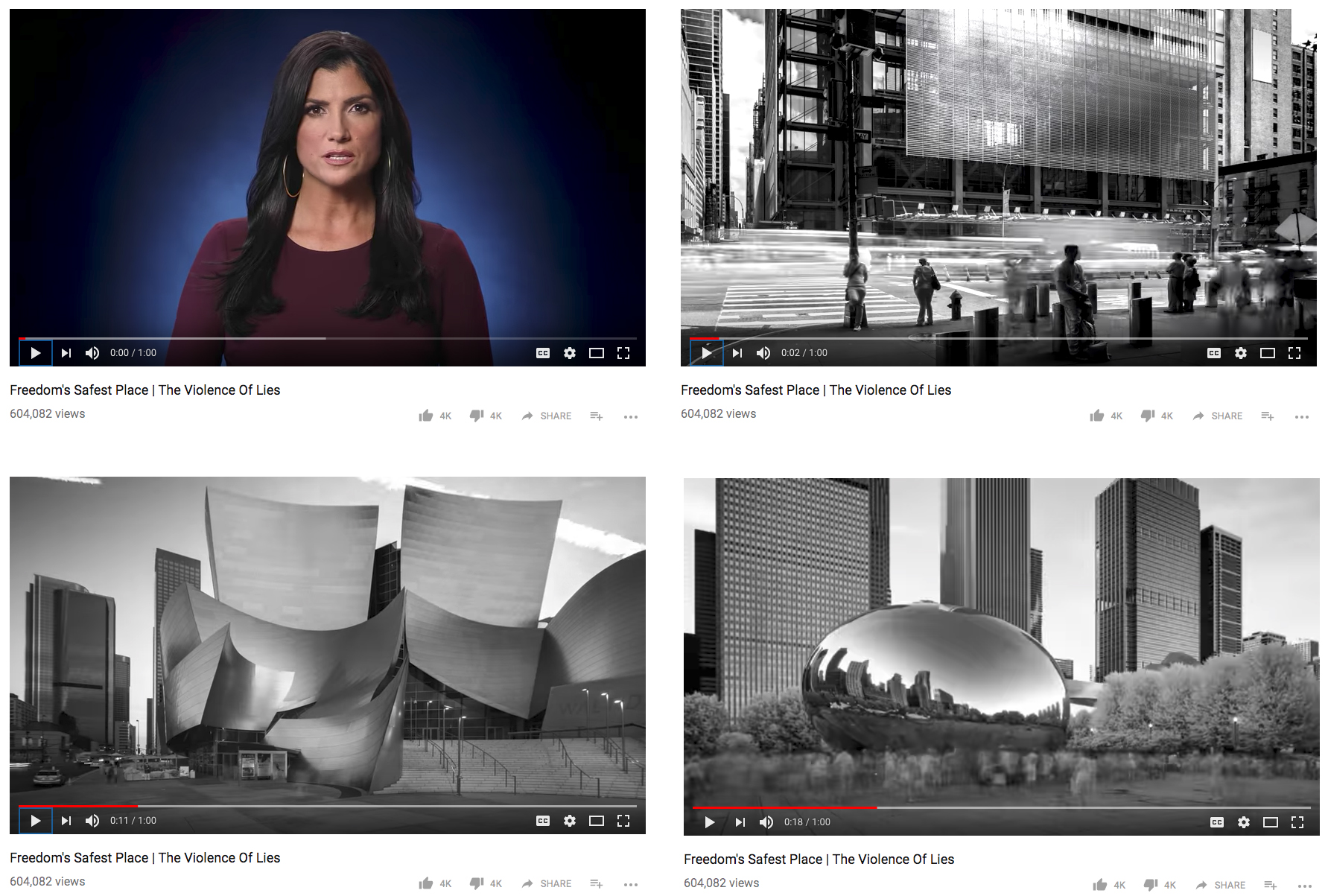

In April, as a part of their snowballing screed against the “Mainstream Media” and cosmopolitan coastal elites, the National Rifle Association (NRA) released a video titled “Freedom’s Safest Place: The Violence of Lies,” in which spokesperson Dana Loesch—in as stark and violent a set of terms as possible—lays out the “us” versus “them” meant to stir up the organization’s membership’s purchasing power.21

With Loesch’s narration running overtop, architecture features prominently as the visual representation of a uniform, globalist culture intent on gobbling up all of middle America’s dearly held local traditions, along with their guns, in the service of neoliberal hegemony. Not only does the New York Times’ endorsement of Hillary Clinton and its disparagement of Donald Trump stand in opposition to suburban conservative values, so does its sleek metal and glass Renzo Piano–designed urban façade. Anish Kapoor’s “Bean” in Chicago reflects an unwelcome, distorted, avant-garde future. The swooping forms of Frank Gehry’s Disney Concert Hall, rendered in black and white against a gray Los Angeles sky, project Hollywood’s blithely indifferent limousine liberalism in a world that’s anything but.

Shortly after the NRA’s campaign rollout, Infowars, outlet of the admitted play-acting conservative hysteric Alex Jones, made this connection between “modern” architecture and global elites even more explicit, posting a video titled “Why Modern Architecture SUCKS, and How It’s Used as a Tool of Social Engineering.”22 In it, YouTube mouthpiece Paul Joseph Watson delivers a by-now familiar diatribe against the soul-crushing dogma of postwar European architects such as Le Corbusier, whose towers in the park, Watson would have us believe, have robbed humanity of all of its hard-won traditions, as exemplified by the apparently “natural” beauty of classical architecture and planning, together with all of its various revivals. Watson lumps certain iterations of postmodern pastiche into his list of enemies, with the British town of Poundbury, promoted by Prince Charles, as the counterpoint: the epitome of what a well-behaved, sensible architecture should look like today.23

It is hardly necessary to break down Loesch’s, Jones’s, and Watsons’s flattening, reactionary positions point-by-point. Suffice it to say that the disciplines of architecture and planning have reckoned with the troubling legacies of modernism for decades, developing a whole range of formal and conceptual movements whose particularities speak to an anxiety that is sympathetic, in many ways, to Watson’s, though thankfully not always resembling Poundbury in terms of results. In other words, architecture has come a long way from the call-and-response of modern and postmodern styles wars. Many architects’ and critics’ willingness to ask probing questions about technology, landscape, sustainability, gender, race, and accessibility, among many other topics, has opened up what was once perhaps a more monolithic world of western architecture and planning practice to innumerable trajectories that contend head-on—in ways conveniently overlooked by arch-conservative, anti-globalist propaganda—with the situated, local complexities of contemporary life.

Now more than ever, architecture is called to mobilize its intersectional skill set to organize responses to planetary crises such as climate change that speak at once in the forceful voice of a true transnational movement while also touching down in sensitive, grounded, and historically informed ways. After all, in propagating these false binaries—local versus global, traditional versus modern, capitalist versus communist, all of which have been long-abandoned by any architecture discourse worth its salt—the NRA and Infowars hope to force equivocation, or perhaps a “slowing down” of cultural shifts that might otherwise stand in the way of all of the gains to be made by those currently holding the reins of power. And it is in this moment that architecture culture cannot afford to back away from the imperative to speak clearly from its nested layers of expertise.

Favoring “slowed down,” reasoned debate need not mean the abdication of a position altogether. Architecture and design unavoidably condition and participate in the public debate over gun control. Alex Jones knows it. The NRA does too. So why don’t the editors of CLOG? Their painting of a “holistic” picture takes the NRA’s bait, offering toothless neutrality as the somehow reasoned response. It reinforces architecture’s outdated, elitist, enlightenment-era self-image just as it leaves the profiteers of gun violence effectively unchallenged.

When it comes to the info wars over gun violence in the United States of America, there is no middle ground ripe for occupation. Rather than lament partisan retrenchment, or continue pretending that architecture might help map a neutral course, it is urgent that anyone with a platform in the field speak the truth—more guns equals more death—with urgency, respect, and clarity.24 Only earnest advocacy, rather than aestheticized equivocation, will bring about the change we so painfully need.

-

Alongside more conventionally understood public health crises such as heart disease or HIV/AIDS, long studied by the Centers for Disease Control and other government entities, gun violence should be treated as a research-worthy epidemic similar to automobile accidents or the opioid epidemic, which have comparable rates of death and injury. Unfortunately, the so-called Dickey Amendment has long served as an effective gag order on such study, link. ↩

-

It is not hyperbole to call this a crisis: death by firearm is increasing for the second year in a row after nearly fifteen years of (already staggeringly high) stasis. Between the time that fifty-eight people were killed in the country’s deadliest mass shooting in recent history and the next spectacularly violent incident on November 4 in which twenty-six more died, nearly 1,400 people were killed by guns, all of whom received next-to-no national coverage. See link, using data from gunviolencearchive.org, as well as link. ↩

-

Despite their recent broadening of subject matter, it seems reasonable to imagine that CLOG remains relatively embedded in the field of architecture in terms of readership. ↩

-

In many ways, CLOG’s five-hundred-word maximum limit for contributions has always contradicted their “slow” mission, effectively mirroring the online forums with which the publication is meant to contrast. ↩

-

See “Small Arms per Sector,” CLOG x GUNS (fall 2017): 132–133; and “Countries with the Most Civilian-Owned Firearms,” CLOG x GUNS, 34–35. ↩

-

See “Timeline of Mass Shootings in the United States, 1982–2016,” CLOG x GUNS, 188–189. ↩

-

See “U.S. Guns and Ammunition,” CLOG x GUNS, 30–31. ↩

-

See “Average Mass Shooter,” CLOG x GUNS, 190–191. ↩

-

See “Trending,” CLOG x GUNS, 192–193. The direct alignment of CLOG’s own passing treatment of the issue with the damaging effects implied by the graph is left unaddressed. ↩

-

Jacob Reidel, “Permit to Purchase,” CLOG x GUNS, 118–119. ↩

-

Carrie Smith, “Murder He Wrote,” CLOG x GUNS, 142–143. ↩

-

See the editorial statement in CLOG x GUNS, 5. The issue includes a piece about the resistance encountered by Guest Editor Ben Nicholson when shopping around a course on guns at various institutions (“Teaching Guns in Art and Design Schools,” CLOG x GUNS, 240–241); the course was offered at Cornell University in the fall of 2017 (similar classes were also offered at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Washington University). That the editors also hosted a launch event planned at Manhattan’s Westside Rifle and Pistol Range (November 10), link, and a CLOG-sponsored “Intro to Shooting” course in Woodland Park, NJ (November 29) attest to this deference toward the apparent need for a somehow rebalanced debate. ↩

-

Some of the claims made by the public relations and communications manager for Glock Inc. (pages 68–71) and the owner at the Westside Rifle & Pistol Range (pages 114–117) are particularly worthy of pushback within their interviews. ↩

-

In addition to their being the disproportionate victims of gun violence, black Americans are also disproportionately affected by low investments in public-health research particular to their demographic. See Molly Rosenberg, Shabbar I. Ranapurwala, Ashley Townes, and Angela M. Bengston, “Do Black Lives Matter in Public Health Research and Training?” Plos One, October 10, 2017, link. ↩

-

See Ann P. Haas, Philip L. Rodgers, and Jody L. Herman, “Suicide Attempts among Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Adults,” the Williams Institute, January 2014, link; Lucy McBath, “It’s Time to Talk about Gun Violence, Hate and Protecting the Transgender Community,” Essence, August 9, 2017, link; Katie McDonough, “‘Where There are More Guns, More Women Die’: A Harvard Public Health Expert Breaks Down the Data on Firearms and Women’s Safety,” Salon, February 24, 2015, link. ↩

-

Richard Florida, “The Geography of Gun Deaths,” the Atlantic, January 13, 2011, link. ↩

-

Mike Spies, “Carry Guard: The NRA’s Controversial ‘Self-Defense’ Insurance Program, Explained,” the Trace, October 20, 2017, link. ↩

-

Linley Sanders, “This Gun Bill Would Mean States Can’t Stop People from Carrying Firearms without a Permit,” Newsweek, October 9, 2017, link. ↩

-

Ashley Hlebinsky, “Displaying the ‘Politically Incorrect,’” CLOG x GUNS, 50–51. ↩

-

Jacoba Urist, “The Architecture of Loss: How to Redesign after a School Shooting,” the Atlantic, November 20, 2014, link. ↩

-

Under the seemingly terrifying tenure of President Obama, this fear-mongering was much easier, and gun sales were much better. ↩

-

See Corky Seimaszko, “Infowars’ Alex Jones Is a ‘Performance Artist,’ His Lawyer Says in Divorce Hearing,” NBC News, link; and Paul Joseph Watson’s “Why Modern Architecture SUCKS” at link. ↩

-

“Poundbury,” The Prince of Wales and the Duchess of Cornwall, link. ↩

-

For recent coverage of the correlation between gun quantities and shooting frequency, see Max Fisher and Josh Keller, “What Explains US Mass Shootings? International Comparisons Suggest an Answer,” the New York Times, November 7, 2017, link. Laying this out in stark terms is not meant to imply that there is no need for nuance within the gun violence prevention (GVP) movement. Particularly when it comes to striking a balance between sensible laws and historically informed racist enforcement, GVP organizations must continue to work on the intersectional aspects of gun regulation, as well as gun violence. ↩

Jacob R. Moore—critic, curator, and editor in architecture—is a contributing editor to The Avery Review and a member of Gays Against Guns (GAG). GAG is an inclusive direct-action group of LGBTQ people and their allies committed to nonviolently breaking the gun industry’s chain of death and to ensuring safety for all individuals, particularly vulnerable communities such as people of color, women, those who struggle with mental health issues, LGBTQ people, and religious minorities. GAG condemns white supremacy, all instances of excessive force by police, and police militarization.