Turn on, tune in, drop out. The catchphrase of the countercultural movement popularized by Timothy Leary highlighted the wanderlust of a generation keen to turn away from society and go off grid. And to resist socio-economic, institutional, and spatial norms by “dropping out” usually meant to move to rural, remote, and mobile communities in order to physically separate from the mainstream or reject systems of capitalist labor. 1 But, how to get there? The Volkswagen (VW) Type 2, the first mobile camper van—affectionately called the kombi in Australia—became a symbol of this free spirit as many hippies, trippers, and droppers left urban centers. 2

The VW hippiewagon may no longer be in production, but some of the countercultural generation—now recast as baby boomers—are still dropping out (or trying it for the first time). In fact, the aging population in wealthy economies has seen an increase in a type of nomadic urbanism, not for the purposes of subsistence from the land, but in fact for very different, leisurely reasons. Seniors are flocking to the countryside in caravans, campervans, and recreational vehicles (RVs). As these “gray nomads” withdraw after a lifetime of work and embark on a life of leisure, they bring their own forms of subjectivity, collectivity, and spatial practices with them.3 Architect Deane Simpson argues that within the nomadic elderly class, radical experiments in contemporary urbanism have emerged—forms of mobile domesticity, sparse networked communities, and plug-in infrastructure—pursued by people who are often typecast as conservative or immobile.4 What can we learn from the context that has given rise to gray nomads and observations around their spatial practices to inform our possible future? What does the unique domesticity of these itinerant senior citizens tell us about the effects of housing policies and what might it portend in a time of rapidly changing labor practices and increasing real estate financialization?

The Upwardly Mobile Senior

Gray nomads were first chronicled in the eponymous 1997 Australian documentary, which explored the lives of elder Australians as they traversed the continent in search of freedom during retirement. The term refers to people over fifty-five who independently travel for extended periods of time, from a few months to over a year.5 It is estimated that tens of thousands of gray nomads are on the road around Australia at any given time. Decoupled from the workforce through retirement, they have a perceived freedom to choose where they want to go and what they want to do. They roam the countryside by caravan, motorhome, campervan, or converted bus, tapping into infrastructures, following the sun, and watching Netflix on the run.

Australian gray nomads are quite different from the North American “snowbird” despite having superficial similarities. The gray nomads of Australia travel farther and move more frequently—with some traveling between three hundred and five hundred kilometers on one day. Gray nomads actively refrain from being “organized” or taking part in “managed” activities and thus avoid resorts or camps, which their North American counterparts tend to prefer.6 The radical lifestyle of the gray nomads means that they travel long distances, move regularly, and are not organized within structured communities at each destination. The occurrence of mobile or traveling retirees is commonplace in Europe and in other developed nations; however, these groups are more likely to buy properties abroad or partake in organized mass tourism.7 Despite these long distances, and unlike their European brethren, Australian gray nomads remain within similar cultural and linguistic groups.

A Home Away From Home

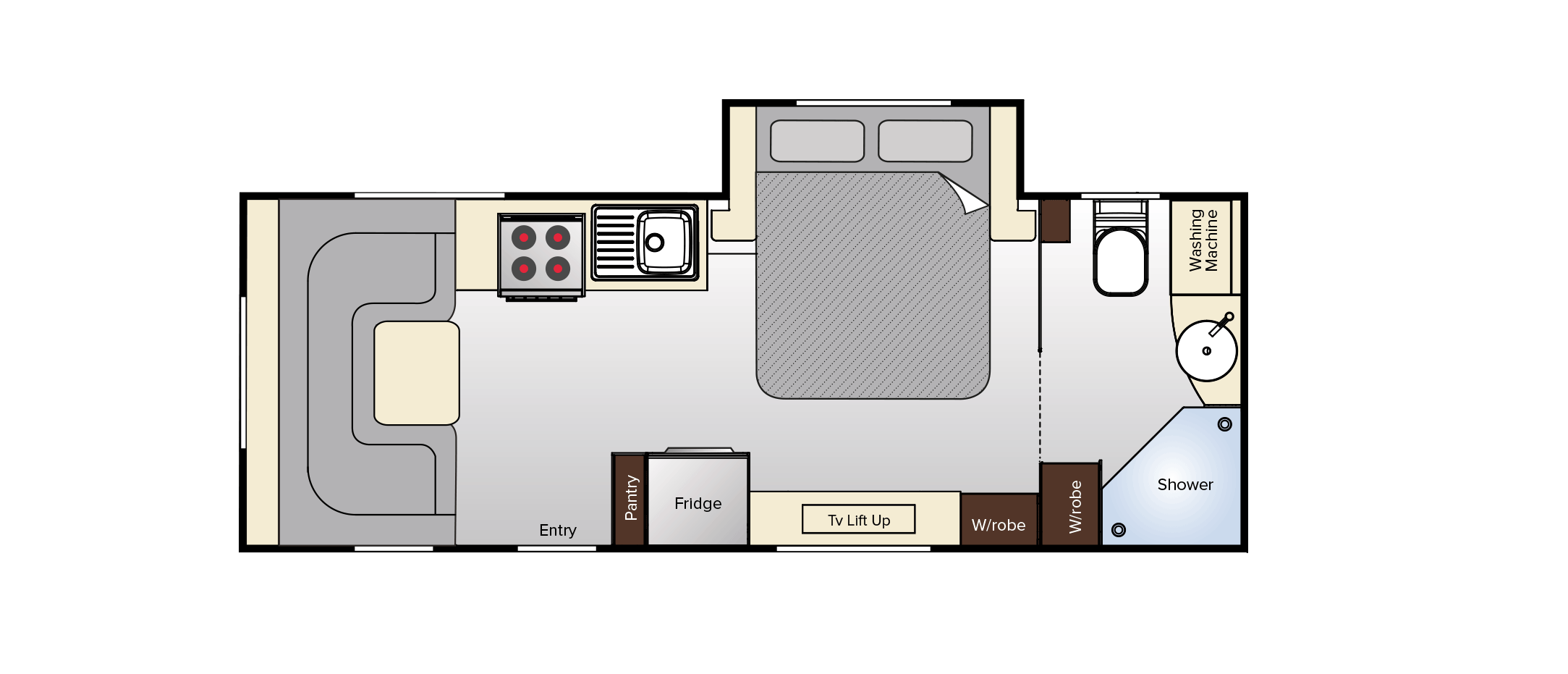

For gray nomads, a home away from home does not mean rejecting the idea of the house entirely. Uprooting the home from its footings onto wheels does not mean that mainstream notions of domesticity are abandoned. Although commonly a single space without “rooms” or spatial divisions, the caravan or RV is often a miniaturization of the typical suburban home—downsizing from an average Australian household size of 214 to 21 square meters. The internal layout replicates the archetypal zones of domesticity, with the “kitchen,” “bedroom,” “bathroom,” and “living spaces” all visible within the interior assemblage. The Avida Topaz Caravan, a top-selling model in Australia, is described on its website as having a spacious bedroom area at the front of the caravan, the living area with kitchen is central, and the bathroom is at the rear.8 The demarcation of space occurs as an instruction to the inhabitants, guiding their domestic behaviors and rituals: the kitchen is for cooking, the bedroom for sleeping, the lounge room for relaxing; although these may also occur within the same unpartitioned space.

Experimental architecture practices of the 1960s and ’70s explored mobile living typologies with innovation and exuberance. Projects such as Archigram’s Walking City (1964) or Mario Bellini’s Kar-A-Sutra mobile living environment (1972) offered radical propositions of dwelling on the move, which rejected domestic assumptions and architectural conventions of the time. Despite this rich precedent, new caravans marketed to the middle class boast customization and personalization to mimic that of suburban mass-produced homes. The Avida website continues: “Options that can be selected to customize the look and feel to match your taste and décor,” including the ability to specify the stone throughout and bench tops, cabinetry colors, floor vinyl, and upholstery. 9 Here the spatial interiors of the caravan or RV reinforce notions of traditional Australian middle-class living and presents the strange paradox that although the way of life is quite radical, the architectural apparatus is not.

Marketing for these vehicles reinforces this paradox; they sell a carefree and nomadic lifestyle without ties to responsibility yet attainable from the comforts of a miniaturized suburban home. Jayco, one of the largest manufacturers of Australian caravans, boasts on its website that its Silverline model will have “enough features to make living easy, your Jayco Caravan will mean never having to go home again. Because home will be wherever you’re parked.” Home can be anywhere and everywhere, but it should still include the organizing principles of the suburban home. The mundane compression of the interior is offset by the extension of the exterior property boundary or the sightlines through the front windscreen possibly to the horizon.

Just as the internal layout and spatial arrangement mimics the suburban domestic environment so, too, does the way the unit interacts with other units and the broader areas in which it becomes stationary. Deane Simpson writes that “this space is frequently organized in a similar way to the typical suburban domestic landscape through the articulation of semiprivate, semi-public, and public spaces as well as the oriented conditions of: “front” and “back.”10 The awning becomes a marker of an outdoor space for socializing and gathering between inhabitants in the caravan park. Lounging in a foldout chair out front signals you are open for a chat and a cuppa tea (or beer if it’s past sundown).

Plugging In

Gray nomads are a highly visible group, often to be seen towing their caravans or driving their motor homes, kombis, caravans, tour buses, and campervans along regional highways and coastal roads, always on the move and rarely staying in a single spot for more than a few weeks. Between these vectors are a network of campsites, caravan parks, and public parking. Here, gray nomads can form temporary and informal community structures that are sparsely distributed across semi-arid or coastal Australia. These networks are continually expanding from official state and local government sites to remote properties linked by informal networks on message boards or advertised sites online (such as youcamp or wikicamps).

When congregating with other gray nomads, basic attractors include free camping places, access to flushing toilets, fuel stops, hot showers, fresh water, shade, and power sites, and the ability to light fires. Beyond these rudimentary amenities however, a study by Mandy Pickering identified that the qualitative aspects of a site were far more important in relation to campsite selection. The attributes of a site were often described similarly to that of an urban block: through an evaluation of its views, location, position accessibility, privacy, and the monetary value afforded by entrance fees to organized campsites.11 It was found that the overarching criteria was the perceived “authenticity of the site,” described in terms of the proximity of natural attractions as well as the perceived “physical and psychological freedom” associated with the site. In the study, the term “physical freedom” was used by respondents to describe a sense of remote physical space, surrounded by an abundance of natural landscapes and elements to explore nearby; “psychological freedom” was the desire to get back to basics and shrug off anything that might tie them to the formalized rules negotiated in everyday life, with physical proximity translating into psychological discomfort. “Another thing we don’t want is suburbia. We’re getting away from that!”12 one respondent professed.

These roadside retirees also have economic pull to remote places. Decentralized living results in corresponding decentralized capital expenditure, with so many gray nomads on the move paying for food, petrol, accommodation, and other services, the “gray dollar” has become an integral part of some rural economies. Roaming gray nomads have revealed much about the effects of a nomadic population contributing to declining rural zones through social and economic capital and labor or volunteering. Many landowners offer work (such as maintenance, gardening, farm help, housesitting) in exchange for a free place to dock or stay over; this contribution through human capital provides a mutually beneficial relationship to rural communities and nomads alike.

After Work

A growth in partaking in this wandering way of life has been made possible by the increased life expectancies in wealthy economies throughout the last century; people are living longer and in better health.13 This shift has resulted in a demographic of active, healthy retirees who are largely free from the burdens of work, study, and family care and at the same time are unconstrained by most of the physical and mental impediments defining traditional old age.14 Over the last forty years, as this cohort has expanded, time spent in “retirement” has transformed from being a phase of inertia to being one now presented as a period of continued personal growth and exploration for the elderly across wealthy economies.

The proliferation of the gray nomad is tied not only to an aging population but to governmental policies of legislated superannuation and homeownership in which individuals and couples fund their own retirement. Currently, in the idealized capitalist economy, the working subject is retained until a time when they can be free to enjoy leisure and explore the unknown where their bodily output is no longer linked to labor or financial production. Nomadism is a reward after a lifetime of permanent work, a rebuff of the societal and economic systems that during the twentieth century largely tied a working subject to a single static place geographically.

The prospect of a wealthy retirement in Australia for this cohort has typically been made possible through the purchasing of property during one’s working life. Baby boomers were assisted by a tool kit of schemes or levers (negative gearing, capital gains tax concessions, first-home owners grants, and record-low interest rates) to buy up big. These assets, with values skyrocketing over the last decade, are then sold or rented to fund the twilight year’s trip. Nearly half of gray nomads interviewed in field research conducted in 2007 admitted that they had sold their homes to finance the trip.15 A mobile life requires the reduction of material possessions—even the house itself. But in the “lucky country” of Australia, the current cohort of baby boomer gray nomads, both Anglo-Australian and comfortably middle class, have profited from an urban life and twentieth-century financial structures to afford their escapism to the hinterland.

However, under current systems where retirement has stretched to twenty-plus years, this twilight zone of leisure is not a realistic future option for a large part of the population who are being asked to work for longer and who may never own their own home. The gray nomad may be just a momentary phase. The extension of a life of leisure may soon impossible as people become so indebted that they are no longer able to retire. While gray nomads are primarily privileged baby boomers, their way of life reveals much about physical and digital infrastructures that support and facilitate nomadic living. This subcultural form of living may instead be a precursor of a life for future generations—not one of nomadic leisure but one of nomadism—following cheaper land, going off the grid or working remotely.

Gray nomads reframe the perception of the elderly from needing concentrated care (retirement homes and hospices) or aging-in-place (in an isolated “empty nest”) into one that requires distributed infrastructure and mobile homes. While this nomadic young-old age may not be a option for future generations, it does offer clues to an alternative form of urbanism that is rural and networked where dwellings are not fixed, lives are uprooted every other day or week, and essential infrastructure (such as water and electricity) are plugged in or produced off-grid. It may signal a future urbanism that is post-geography, where the city has no boundary. Or can this way of life provide some insights into how society might live when labor is removed through automation and we go off searching for experiences in a life of endless leisure?

-

Felicity D. Scott, “Episodes in the Refusal of Work,” Volume 24 (2010): 34–39. ↩

-

Deane Simpson, “RV Urbanism,” in Media and Urban Space: Understanding, Investigating and Approaching Mediacity, ed. Frank Eckardt (Berlin: Franke and Timme, 2008), 233–258. ↩

-

Deane Simpson, “Mobilities of the Third Age,” in “Nordic Seniors on the Move: Mobility and Migration in Later Life,” ed. Anne Leonora Blaakilde and Gabriella Nilsson, Lund Studies in Arts and Cultural Sciences, vol. 4 (2013): 203–220. ↩

-

Simpson, “RV Urbanism,” 233–258. ↩

-

Jenny Onyx and Rosemary Leonard, “Australian Grey Nomads and American Snowbirds: Similarities and Differences,” Journal of Tourism Studies, vol. 16, no. 1 (2005): 61–68. ↩

-

Onyx and Leonard, “Australian Grey Nomads and American Snowbirds,” 61–68. ↩

-

European Union, “People in the EU: Statistics on an Ageing Society,” Eurostat: Statistics Explained, June 2015, link. ↩

-

Deane Simpson, Young-Old: Urban Utopias of an Aging Society (Zurich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2015), 472. ↩

-

Mandy Pickering, “Towards an Understanding of the Grey Nomad Consumer” (Master’s thesis, Edith Cowan University, 2004), 64. ↩

-

Pickering, “Towards an Understanding of the Grey Nomad Consumer,” 40. ↩

-

William Reece, “Are Senior Leisure Travellers Different?” Journal of Travel Research 43 (2004): 11–18. ↩

-

Simpson, Young-Old: Urban Utopias of an Aging Society. ↩

-

Jenny Onyx and Rosemary Leonard, “The Grey Nomad Phenomenon: Changing the Script of Aging,” Journal of Aging and Human Development, vol. 64 (2007): 381–398. ↩

Amelia Borg is a director of Sibling Architecture and the inaugural recipient of the Steve Ashton Scholarship for the Architectural Profession.

Timothy Moore is a director of Sibling Architecture, editor of Future West (Australian Urbanism) and lecturer in architecture at Monash University.