“Flood insurance optional.” In its bygone bull market patois, the Arverne by the Sea pitch is nothing short of optimistic. No mandates for the overheads of storm protection here, scant feet from the Atlantic Ocean. Instead, like the premium finish on oak-paneled floors, it’s optional. On the coast of Queens, New York, in the sales office of this 308-acre residential development, real estate agents are keen to sell the last unoccupied single-family homes. Prospective buyers—this author masquerading as one—are greeted by exuberant projections and statistics. Guides are eager to tour, eager to loan, and eager to assuage fears of high price points or rising tides. In an era of risk management, it may be surprising that insurance is opt-in. But it is symptomatic of a culture of customization. In a community that is presented as an exemplar of resilience, it is also a telling detail in a story about design, disaster capitalism, and the affordability of the social safety net.

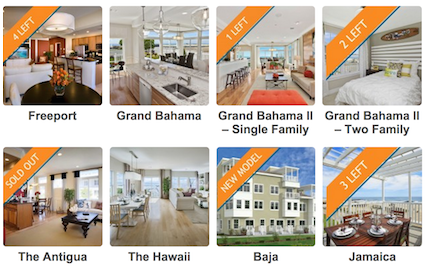

The neighborhoods of Arverne rest on the highest points of the Rockaway peninsula, a meter or so above sea level.1 These townhomes and condominium towers, many still under construction in 2012, were spared the destruction of “Superstorm” Sandy, when storm surge and floodwaters inundated the adjacent public housing towers and beach cottages, marooning their residents. As the high water seeped into bungalows and apartment blocs, it only lapped along the sides of Arverne, making an island of the development. At the peak of its tide, the hurricane created a geography that the developers, Benjamin Companies and the Beechwood Organization, had always aspired to—a waterlocked vacationland, a topology like the eponyms of the model homes it offers (Jamaica, Freeport, Antigua, and Hawaii, to name a few).2

Arverne’s signature houses are peculiar heterotopias, built in the imitable style of housing subdivisions found everywhere from suburban New Jersey to the outskirts of Astana, Kazakhstan. They come with the trimmings of a Carolina beachfront abode: balconies like miniature widow’s walks, porches clad with white rails. White plastic trellises ornament the façades. And while the different house typologies (distinguished by their varying floor plans and square footage) are named for well-known holiday destinations, none take on a local or regional style, nor do they attempt to make any reference to being in or even near New York City. Instead, as narrated in a video tour, Arverne is located at, “the intersection of location, luxury, and lifestyle.”3 It is New Urbanism at its most resplendent: spectacularly quotidian, Pleasantville chic. The design by Ehrenkrantz Eckstut & Khun (the firm that did the master plan for Battery Park City) has been described as “Saltwater Taffy Revival,” “Florida by the Subway,” and another “billion dollar luxury complex.”4 It has also been praised for bringing “community” to Rockaway Beach.5 6 It’s true, the development fills a void—a quite literal one. Now 664 of the 826 homes are filled. Two hundred fifty-six condos have sold, and 900 are slated to be built next year. But until Benjamin and Beechwood began building in 2002 the more than 300-acre site sat vacant, a fallow field that symbolized the empty promises of urban renewal.7

Slum clearance under Robert Moses was like taking a squeegee to the city and then shaking it off, hoping that the poor would dissipate into the urban landscape. They didn’t. Residents of Rockaway stayed, and as the beach failed to attract vacation homes or weekend pleasure seekers, Moses simply used the open land for public housing, putting up towers for low-income New Yorkers and zoning for little else—there wasn’t much incentive to bring businesses to a place of such hamstrung liquidity. As Title I was used to reconfigure much of Manhattan and the Bronx, public housing towers continued to be relegated to the city’s margins.8 In 1965 the New York Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) designated the eastern end of the peninsula—the areas of Arverne by the Sea, Edgemere, and Arverne East—an urban renewal zone. In 1969 they razed much of it, making way for 6,500 proposed units of housing.9 Then came the fiscal crisis of the early ’70s, notorious disinvestment, and paralyzed city budgets. The lots stagnated for the next thirty years.

On many levels, building here has undoubtedly done the neighborhood good. Near the A train at Beach 67th Street, a Stop and Shop has gone up, the only supermarket for several miles. Underneath the elevated track there is now a dry cleaner (the neighborhood’s first), a smattering of restaurant chains, and a surf shop. A YMCA will open soon. During a tour of Arverne’s model homes, salespeople are quick to point out these firsts, and they’re not wrong to boast. Few would argue against accessible groceries and exercise. But are we consigned to accepting New Urbanism and private investment as the only recourse to basic amenities? Is Pier One domesticity and a three-car garage in one of the world’s most transit-networked cities the trade-off for growth in a once blighted neighborhood?

“Adding value” to the neighborhood is also a good thing. Mixed income makes for diverse communities, improved public services, and local spending. The argument is that developments like Arverne by the Sea will bring more money to the area, along with better schools, community services, etc. But in an area where we should be questioning the prudence of building at all, is this really the right rationale? Tom Angotti, director of the Hunter College Center for Community Planning and Development, predicts that as policy mandates more stringent requirements for housing in vulnerable areas, governmental support will tend to go to designs that are able to employ the most advanced, most complex, and, therefore, most expensive flood protection.10 In this scenario, then, the kind of housing that will end up being built is costly and therefore less accessible to lower-income families. By insisting on “resilient” design instead of flexible, adaptive planning—an approach that might, among other things, better heed the barrier nature of barrier islands—the waterfront will become a territory of the better off, a place where the image of technological expertise (synonymous with safety) is embodied in buildings, and where social housing then becomes less feasible. Arverne’s architecture and its marketing already spin imaginaries of affluence, in flagrant denial of a long history of public housing and populations still in need, while economic assessments of social housing often focus on optimizing capacity or creating communal spaces.

To tour the Grand Bahama III is to weather an onslaught of cookie-cutter domesticity: It gushes with orchids, area rugs, and manicured sod. One can picture the covey of ladies on the promotional literature returning here to put their feet up, uncork a bottle of Pinot Grigio, and gossip. In the advert their arms are thrust forward, laden with a confection of shopping bags in a bizarre gesture of solidarity with the forthcoming mall.

Despite its out-of-the-way-ness, this place is emblematic of resilience, not just the sort associated with a post-hurricane rhetoric promoted by New York City government and the media but also a larger cultural attitude toward risk and threat: a retreat into the security of American stereotypes. Three-car garage, why not? We can face our SUVs to the sea and wonder why it’s rising. In the style of a propaganda poster, Arverne’s logo depicts a woman facing the shore, small child in hand. A partition separates her from a man wading in the waves. On the horizon the sun is radiant, orange, and overpowering; the future is safe and bright.

“Florida by the Subway” is a casual epithet, but it’s also a metaphor. Yes, there is the Clearwater condo-ization of the shoreline. There is the flat coastal geography—but beyond the flatness of the state, there is flatness as a state of mind, that too easy flatness evangelized by Thomas Friedman in which the world is created in the image of the neoliberal bourgeoisie.

Laying grass on top of sand, as the picketed lawns of Arverne do, refuses the facticity of the land. When landscape speaks in the croaky whisper of a palimpsest, when, in its replicability, architecture rubs out the physical particularities of its site and ignores a fraught inheritance of housing, we risk muting the angel of history. To not learn from the past is sad but commonplace; to not learn from what happened in the last five years is absurd. Suburbs and subdivisions are incubators of othering, historically rising from white flight, and recently bankrupting those who believed they were only a loan away from the “American Dream.” Why we would want to take a vulnerable geography and turn it into a suburb is unclear. Despite Mayor Bloomberg’s claim that breaking ground in Arverne ended forty years of “deferred dreams,” the city government still hasn’t made good on its promise for public housing. Given that, why not funnel resources and attention to subsidized housing across Jamaica Bay instead of lauding private development? Why not create meaningful open public spaces to bulwark the Rockaways? In Resilient Life, Brad Evans and Julian Reid invoke the work of cultural critic Henry Giroux. Giroux observes that we are living in an age in which social responsibility has been replaced by neoliberal care of the self, in which Benjamin’s angel of history has been blinded.11 So now, instead of the storm of progress blowing from paradise, we ready ourselves for a different kind of weather event—a hurricane of denial. If the city continues to dilute its social contract by relying on private development, and if government relegates the mitigation of risk to the free market, we’ll continue to marginalize the urban margins.

Benjamin and Beechwood, and their salespeople, don’t appear to forecast that any storms more severe than Sandy will touch down. Arverne by the Sea did emerge from the hurricane barely scathed. Partly it was due to topography, but it was also thanks to sidewalk drainage and raised foundations. Despite being in Evacuation Zone A, many of Arverne’s residents refused to leave. While preparedness breeds hubris, it also turns houses into bunkers: bolt the door, stock up on canned food, and defend yourself from the world without. It’s a critique levied on gated communities, where exclusionary architecture perpetuates fear and turns citizens into trespassers.12 Brazen decisions to stay home aside, the same culture of fear is operating here, this time aimed at the environment, not the people. In Resilient Life, Evans and Reid argue that the rhetoric of resilience, so popular to twenty-first-century governance, infuses daily life with a sense of danger.13 As analysts and politicians turn to resilience as the organizing doctrine of legislation and planning, they create a social climate of assumed vulnerability and risk as opposed to looking for new political models, new financial systems, and new modes of living. For Evans and Reid, this is a form of control that erodes individual agency. In their view, our contemporary breed of ecological thinking, signified in the concept of the Anthropocene, among other things, undercuts humanism, optimism, and personal political will. This point is debatable, but an age of resilience merits skepticism for several reasons. What is most unsettling is its insistence on the status quo.

If we think of the human as a causal, responsive subject, mutualistically connected to its habitat, the rhetoric of resilience seems misplaced. It’s an inflexible language, connoting strength, perseverance, and ultimately domination. Like the head of Medusa, the resilient subject rebounds from disaster, distinct only in her amplified vigor. But with this renewed display of strength, what are we proving? If we emerge resilient, what are we reemerging as? Resilience pits man against nature in a sublime, terrifying, and ultimately counterproductive way.

Nevertheless, in the face of this resilience, there are places where the elasticity of the city is palpable. To be beyond the boardwalk, sitting on the beach is its own sublime experience. It is to be nowhere and everywhere all at once, that strange zone of drifting—perhaps residing there is a moment of optimism upon which Evan and Reid insist. The beach was, at one point before urban renewal, supposed to be this great leveler, in the times where people came in droves to the shore. That’s why people return here now, to relieve certain pressures of the city while still getting caught up in its vibrancy.

As the nature of work and of capital has changed the harbor waterfront, the Rockaways are receiving an influx of the artists and young people pushed out during that sea change. Playland, for instance, is a new “lifestyle brand” that has moved into what was the abandoned Playland motel. Its breed of adaptive reuse tends toward the precious—the owner has partnered with Williamsburg culinary magnate Bolivian Llama for a “food experience”—but it rides the heels of cultural initiatives generated by new Rockaway residents: things like houseboats built out by artist collectives, community galleries, new restaurants, and the arrival of people like musician Patti Smith or curator Klaus Biesenbach, who have both bought homes here. This wave of gentrification is complex and if on a certain level predictable and trite, not necessarily an entirely bad thing. What’s strange is how it has been co-opted by Arverne’s marketing team. Included in the folder given to prospective buyers is a Financial Times article hailing the “cultural metamorphosis” that has come to the neighborhood.14 Despite the fact that new condominium high-rise to go up in Arverne is not quite in sync with the houseboat-refurbishing, Patti Smith–listening crowd, the Williamsburg vibe slowly coming to the peninsula has its own marketing cachet.

Henry Giroux points out that neoliberalism replaced social progress with individual actions, values, and taste. Here, the social is no longer of the public or of the commons but rather of socializing and its attendant cultural capital. It is tied to the land only insofar as it increases real estate values, and as it justifies the need to build in a place where people and their houses must be resilient. In spite of its aging public neighbors and unfulfilled promises of administrations past, this kind of development forecloses the chance to reimagine and reprogram the relationship between the social, housing, and the land. Maybe then in the Rockaways we’ve reached the moment of which Giroux writes, in which Benjamin’s angel of history is “stuck in a storm without a past, and without and consideration for the future.”15

-

"Neighborhood" is a designation given by the developer to denote parcels of land with different kinds of housing and in which the homes are sold in successive intervals. “The Dunes,” for instance, is a tract of 270 two-family homes. ↩

-

Others: East Hampton, Grand Bahama, and Baja. ↩

-

Benjamin Beechwood Dunes LLC, “NBC Open House,”arvernebythesea.com/nbc-open-house, accessed November 6, 2014. Here “location” is no longer an actual place or set of coordinates but rather a term connoting proximity to valued geographic conditions. ↩

-

Phillip Nobel, “This Is New York?” New York magazine (April 19, 2010), nymag.com/nymag/rss/realestate/65358/index1.html; Constance Rosenbloom, “Florida by the Subway,” the New York Times (January 22, 2010), nymag.com/nymag/rss/realestate/65358/index1.html; Arun Gupta, “Disaster Capitalism Hits New York: The city will adapt to flooding—but at the expense of the poor?” In These Times (January 28, 2013), inthesetimes.com/article/14430/disaster_capitalism_hits_new_york. ↩

-

During the ribbon-cutting speech, Mayor Michael Bloomberg declared that the opening of Arverne signified the end to, “40 years of dashed hopes and deferred dreams for the Arverne community.” New buyer and publisher of the Rockaway newspaper The Wave, Susan Locke said that with only fifty homes built, the development signifies a turnaround in a neighborhood that, “fell apart.” See: Virginia Gardiner, “Arverne by the Sea Marks a Rockaway Renaissance,” Planning, 71.1 (January, 2005). ↩

-

Underlying these comments, particularly Locke’s, is a racist divide between black and white residents in the Rockaways. Michael Bloomberg does, though, seem to be invoking the black poet Langston Hughes writing about Harlem, another New York neighborhood to suffer at the hands of Title I. Considering the history of slum clearance, the question Hughes poses in the poem is prescient. “What happens to a dream deferred?/… does it explode?” See Langston Hughes, “Harlem,” Selected Poems of Langston Hughes (New York: Random House, 1990). ↩

-

For more on the history of Arverne by the Sea and the future of Arverne East, see the Architectural League of New York’s series Renewing Arverne: http://archleague.org/2014/04/renewing-arverne/. For more on the history of housing, real estate, and public investment in the United States, see “House Housing: An Untimely History of Architecture and Real Estate in Nineteen Episodes,” a research initiative and exhibition by the Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture: http://house-housing.com/. ↩

-

Title I of the 1949 Fair Housing Act, “Slum Clearance and Community Development and Redevelopment,” allocated grants to city governments to assist in slum clearance and subsequent urban renewal projects. Title I was well-loved by Robert Moses, who felt the act gave him carte blanche to raze parts of the city he wanted to develop—like Lincoln Center and the area where the New York Coliseum went up—and to eradicate poor neighborhoods throughout the five boroughs. ↩

-

This history according to Arverne: “In 1965 Arverne was designated an Urban Renewal Area, and by 1969 the Department of City Planning decided to breathe new life into this little bit of paradise, clearing the area to make way for all-season regional and local recreatio¬nal developments and large-scale housing projects as per the Plan for New York City.” Benjamin Beechwood Dunes LLC, “What is the History of Arverne by the Sea?” http://www.arvernebythesea.com/what-is-the-history-of-arverne-by-the-sea/, accessed November 6, 2014. ↩

-

In Gupta, “Disaster Capitalism Hits New York: The city will adapt to flooding—but at the expense of the poor?”Gupta quotes Angotti saying, “Chances are, public policy is going to support only those developments that are high end, and are able to muster the most sophisticated and advanced flood protections.” Gupta himself goes on to say, “Scientists say that by the time sea levels rise by one meter—which could take from 50 years to more than a century—barrier islands such as the Rockaways will have to be encircled by levees to survive. So until then, if left unchecked, wealthy homeowners and middle-income renters will continue to flock to these desirable waterfront regions.” ↩

-

Brad Evans and Julian Reid, Resilient Life: The Art of Living Dangerously (Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2014), 46. ↩

-

The killing of Trayvon Martin in a Sanford, Florida, subdivision in 2012 was an emblematic and enraging example of this logic. Not only did it reveal a national permissiveness of violence, it also called into question the collusion of architecture and vigilantism. See, for example, Mitch McEwen’s article in the Huffington Post: huffingtonpost.com/mitch-mcewen/what-does-sanford-florida_b_1392677.html. ↩

-

“Resilience is the ability of a system and its component parts to anticipate, absorb, accommodate, or recover from the effects of a potentially hazardous event in a timely manner, including the preservation, restoration, or improvement of its essential basic structures or functions.” Evans and Reid, Resilient Life. ↩

-

Emily Nathan, “The Rockaways Reborn,” the Financial Times (February 21, 2014), ft.com/cms/s/2/12b77076-988b-11e3-8503-00144feab7de.html. ↩

-

Evans and Reid, Resilient Life, 46. “Recounting Walter Benjamin’s comments on Paul Klee’s Angelus Novelus, Giroux stakes out here the shift from utopians to the embrace of the catastrophic and its penchant towards the violence of the encounter…Benjamin’s ‘Angel of History’ has been blinded and can no longer see the destruction beneath its feet or in the clouds paralyzing its wings. It is not stuck in a storm without a past and lacking any consideration of the future.” ↩

Caitlin Blanchfield is Managing Editor in the Office of Publications at Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation and an editor of the Avery Review.