It is in the City’s best interest to begin conversations with the community as early as possible, before the formal legal processes begin.

— Lippman Commission (emphasis added)1

#ICYMI

It has been two years since then–New York City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito established the Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform that studied the condition (and considered the future) of the city’s criminal justice system.2 In the year following Mark-Viverito’s call for “More Justice,” numerous public actions, increased reporting, and mounting public pressure to #CloseRikers were met with mayoral wavering in an already established climate of renewed public political activism, including concurrent organization around #BlackLivesMatter and infrastructure-focused calls to action including #ShutItDown.3

It has been a year since the Independent Commission (commonly referred to as the Lippman Commission) released its initial report—indicting the criminal justice system broadly and Rikers Island Correctional Facility (Rikers) specifically, outlining the many ways in which one of the world’s largest penal colonies is too wasteful to justify investment, too damaging to rehabilitate, and ultimately too broken to fix.4 Its primary findings and recommendation warrant repeating: “… simply reducing the inmate population, renovating the existing facilities, or increasing resources will not solve the deep, underlying issues on Rikers Island. We are recommending, without hesitation or equivocation, permanently ending the use of Rikers Island as a jail facility in any form.”5 It was a long-awaited, first-step victory for those who had worked for years toward the facility’s closure.

Further, the Commission’s report put forth a series of principles, both explicit and implicit—by listing Riker’s demerits in financial, administrative, legal, political, architectural, urbanistic, and humanitarian terms—to which the planning, design, and operation of New York’s detention and incarceration infrastructure should adhere. The most straightforward:

In place of jail facilities on Rikers Island, the Commission recommends the construction of five state-of-the-art jails, one in each borough. These jails—which would be situated near courthouses in civic centers, rather than in residential neighborhoods—would be more accessible and would reduce transportation costs.6

It has been eleven months since the Mayor’s Office first announced its intention to close Rikers, followed shortly with a plan, Smaller, Safer, Fairer: A Roadmap to Closing Rikers Island. Largely in line with the Commission’s recommendations, the official plan established a ten-year timeline to first reduce the detained population and then to shutter the facility.7 Since then, the Mayor’s Office has beat a few expectations, announcing the plan to close the first facility—George Motchan Detention Center—by the end of this summer.

It has been ten months since the Van Alen Institute released its report on the topic, Justice in Design. The publication resulted from the work of an interdisciplinary team led by architects and planners chosen via a juried process organized by the institute. The project was co-sponsored by the Lippman Commission and offered a follow-up supplement to the Commission’s findings.8 It has been seven months since The Architectural League of New York’s Urban Omnibus launched their ongoing, online series “The Location of Justice,” offering architectural and urbanistic journalism on the contentious and still-evolving collective project of moving toward the City #AfterRikers.9 Together, these institutions’ projects comprise the public architectural contribution to this process, albeit with very different formats and approaches. While the Architectural League has focused on analysis and reporting, it was the Van Alen report that circulated as the image of the Commission’s (and often by association, the City’s) plan.

It has been three months since Mayor de Blasio announced the four replacement locations chosen to accommodate Rikers’ closing. The proposals include expanding capacity at existing detention centers in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens and building a new facility in the Bronx. These locations were identified through a research and planning study contracted to Perkins Eastman—a global architecture firm with experience in extensive criminal justice and corrections projects from Poughkeepsie to Abu Dhabi—a few months prior. 10

And this brings us to #WhereWeAre—a moment when lines have been drawn, a moment with passionate public hearings and emotional community gatherings, a moment of predictably high-intensity responses to high-stakes questions.11

#AsEarlyAsPossible

I believe this is also a moment when we can and should reflect upon the decisions made for the first-and-only chance “to begin conversations with the community as early as possible.”12 As the Lippman Commission anticipated, there are precious few opportunities to frame the substance and tone of this discussion—which now includes almost everything from engaging community concerns, countering misinformation, and finding common ground to questioning the City’s plan for a combined public review process and deciding which stakeholders carry official, recognized, and effective stakeholder status.13 There are very few chances to establish platforms that transparently acknowledge the many conflicts and opportunities in this debate without belittling or misleading communities through oversimplification. #AsEarlyAsPossible was not only a fleeting moment for the City but also a rare moment for architecture because, as it turned out, the earliest broad, public engagement with an accessible and legible description of possible futures was put forth by designers. This was an opportunity to bring disciplinary expertise to bear on complex scalar issues, to draw and draw out the spatial dynamics of sociopolitical infrastructures, and to describe and design the ways in which building practices participate in justice systems.

Justice in Design—a contribution by architects and planners, rather than solely criminal justice specialists and jurists—was what resulted from the Van Alen taking up that chance. And now, before the process of trying to replace Rikers completes its course, is a worthwhile moment to reflect on the implications of their decisions, whether corroborating or questioning, elaborating or evaluating, problematizing or prototyping. The planned closure of the country’s largest jail in its largest city renews fundamental questions on the roles and responsibilities of urbanists with respect to whether and how to involve ourselves in systems of incarceration. We have seen several such roles performed in this process, but the Justice in Design team modeled theirs very publicly at a pivotal moment—and in so doing they established terms, framed issues, and raised questions we should confront.

From its contents and scope, Justice in Design appears to serve a singular purpose: translating the Lippman recommendations for a wider public through the schematic illustration of a county jail within a “prototypical urban context.”14 Without question, this purpose was an interesting exercise in architectural illustration and visual communication. It was also important. The analysis and findings included in the Lippman report are dense, layered, and complex. For an unfamiliar reader, it is reasonable to imagine frustration attempting to connect one chapter to the others. In communicating those findings to a broad audience of potentially affected communities, the Justice in Design contribution is substantial.

To be clear, while the Justice in Design project was based on the Lippman Commission’s work, the Commission's specific recommendations are not under review here.15 Rather, a consideration of the Van Alen project warrants evaluation on its terms, with respect to its aims, and set against its opportunities. If one accepts the premise of jailing, then the county jail model makes sense: while the consolidation of the City’s five borough-counties arises from certain administrative, bureaucratic, and logistical interdependencies, the Commission’s evidence that such consolidation within our justice infrastructure fails to meet those needs is overwhelming. Should the City manage to reduce its detained population by the proportions planned, a centralized Rikers would still constitute one of the largest jails in the country.16 Jail surveys and censuses regularly report that smaller jails feature higher turnover rates and, accordingly, that larger jails detain individuals for substantially longer periods of time.17 And so while protecting individuals from ever entering Rikers seems a self-evident first step, it may also be true that simply breaking up the facility could significantly decrease the city’s average daily incarcerated population. But the problem of size is not the problem of scale—the former is more symptom than cause, and the latter constituted a concrete opportunity for the Justice in Design team to lead a productive discussion on urban systems of incarceration.

#ScalesOfJustice

The scalar questions of integrated urbanism are numerous. With respect to the problems put before the Justice in Design team, they can be minimally defined as questions at the level of the city and at that of the neighborhood—and, indeed, they are presented as such. More specifically, however, scalar consideration is not a matter of mere zoom level. It includes the issues and complexities that arise between situated elements of different sizes (and often at different times).18 In other words, for this discussion, the “scale of the city” includes more than describing large systems within a map of the city but also describing the relationships between these systems and their smaller, constituent parts—each understood at particular locations and active at specific moments. By this, zooming into a neighborhood would necessarily require describing more than the details afforded by higher-resolution inspection, more than illustrating the ways that city-scaled systems touch down in particular places. It also involves specifying the relationships between these systems and neighborhood-level resources, processes, and their localized organization. Scale as distinct from size—as relationships between elements of different sizes—is the site of urbanists’ and architects’ domain expertise, whether in the design and execution of participatory engagement processes or in the strategic development and consideration of on-the-ground experiences, spatialities, hierarchies, trade-offs, and priorities. When mapping jails onto the city, these questions are also the point of intersection between criminal justice, corrections, court systems, and the city itself, and thus must be the primary target for design intervention and influence.

While not established in these explicit terms, the relevance and urgency of such a scalar framework are clear through the Van Alen report, which operates at two scales: that between Rikers and the city’s networks constraining the flow of goods and people and that between proposed jails and neighborhoods connecting communities and situating services. The promise of these co-considered scales offers insight beyond policy to decision makers and New Yorkers alike—an understanding of the Commission’s implications as well as a scalar understanding of corrections throughout the city. Moreover, the Justice in Design team’s mandate explicated a few particularly scalar considerations, not the least of which is summarized as “What impact does jail have on the community, and how can a decentralized jail system improve these negative effects?”19 In other words, it was precisely within the discovery and delineation of sociospatial scalar issues (those outside the scope of the Commission’s expertise) that the project’s greatest potential rested, upon which its relevance relied, and from which its effects would be rendered.

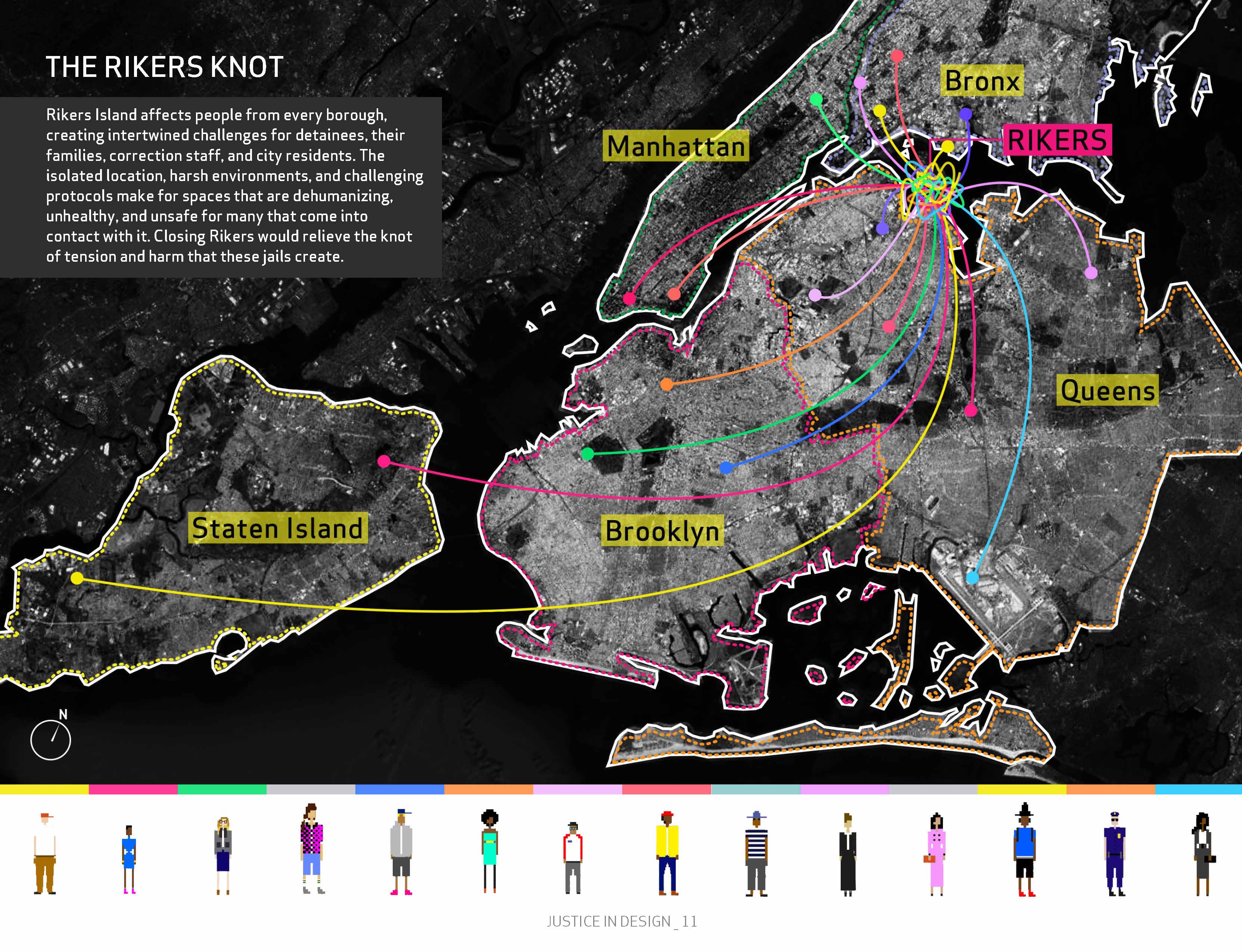

Toward the first scale, where the city meets Rikers: In its present condition, the architectural and infrastructural systems of management and control regulating the flows of supplies and individuals are multifaceted and materially present, although largely invisible to most New Yorkers. They include nested layers of checkpoints and thresholds that bodies must cross (at precincts, central booking sites, and so on), elaborate choreographies of identification and verification (with coded, laminated ID cards), as well as dedicated buses serving populations both on and off the island. These are mechanisms with ripple effects well beyond the edges of Rikers and impacts beyond the boroughs’ courthouses and precincts. The facility’s location and protocols conspire to complicate routines as foreseeable as family visits and as commonplace as officers’ shift changes. Yet each of these interactions, interruptions, transactions, and negotiations is absent from the drawings’ analysis. These are systems with a physicality that could be immediately and accessibly rendered through analytical architectural drawing and cartography for communities—including those facing proposals for new or expanded jails, most of whom are presently burdened with the backlogged extensions of these flows. Instead, in Justice in Design, these movements are represented unexamined, simplified, and reduced to aerial arcs converging without discernible order or logic in a drawing described as the “Rikers Knot.” 20

Alas, just as physical infrastructures are not the only citywide problem plaguing Rikers, they are also not the only systems requiring attention at this first scale. The overlapping spatial intricacies of criminal justice—with its labyrinth of human processing at nodes across the city—was yet another opportunity for analysis, engagement, and public pedagogy through critical drawing lost at a critical moment.21 While the locational and logistical conditions at Rikers Island certainly warrant its closure, it is #NotTheKnot that keeps individuals imprisoned there. Rather, the tangled and varied criminal justice system involving policing, arrest discrepancies, bail practices, detention, legal representation, incarceration, and probation that choke our courts and our communities in daily routines and annual cycles were all worthy (and necessary) candidates for drawn exploration and engaged explication at the earliest moment possible. The description of this system’s bottlenecks, shortcomings, and inequities are clear in the Commission’s report in juridical and corrections terms, but such description cannot reveal their cumulative ramifications at Rikers and subsequent reach into the spaces and experiences of everyday life across the city. This charge falls squarely within the domains of architectural and spatial consideration and yet is conspicuously omitted from the Justice in Design analysis.

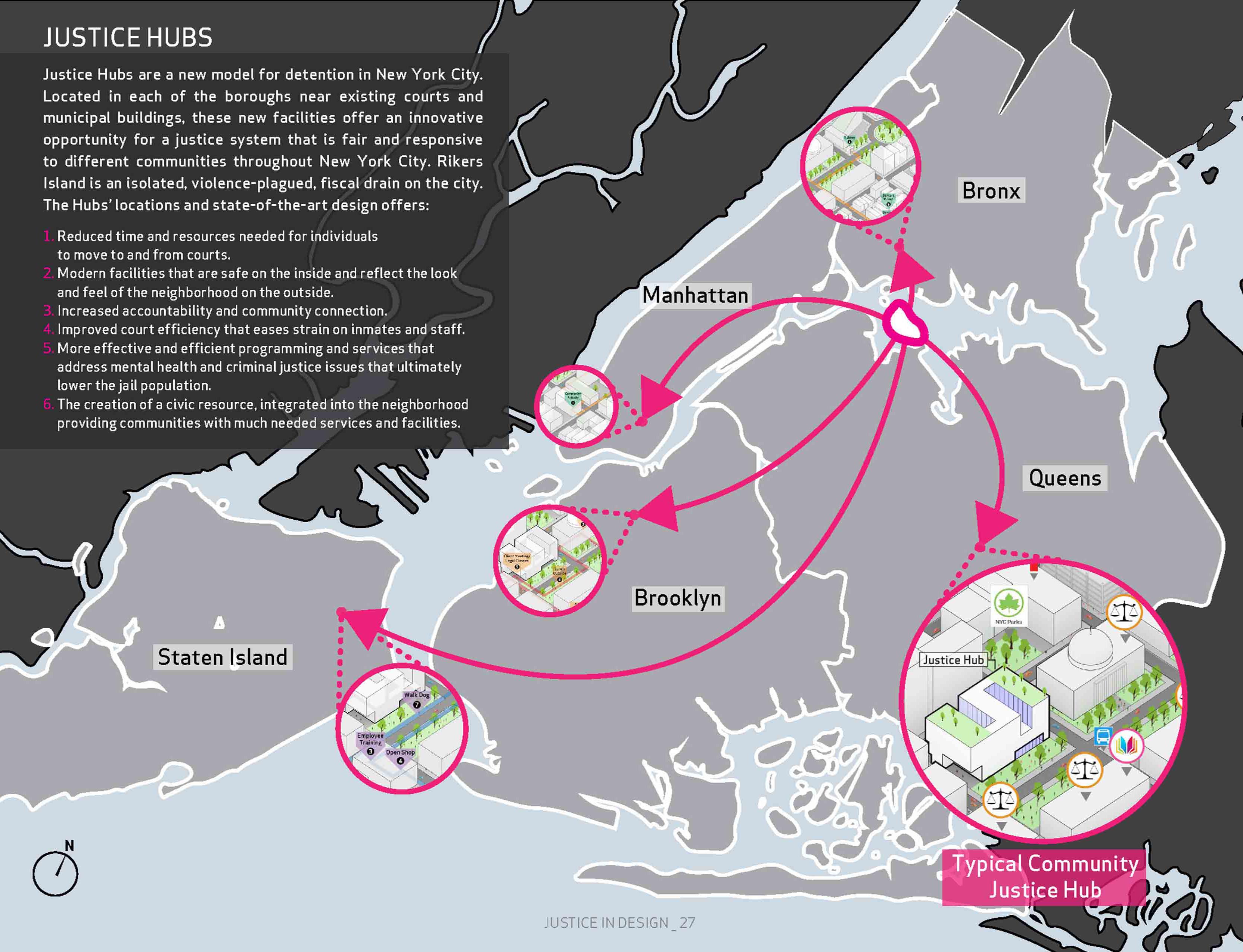

Moving beyond problems and toward the graphic description of proposed solutions at this scale, the expectations and opportunities were many. One expects to find a visual analysis of the relationship between geographically networked institutions of various sizes—considered in terms of their constituencies and jurisdictions, their resources and reach—and of the realpolitik of intracity spatial bargaining that determines outcomes within this complexity. At minimum, one expects to find assessment and depiction of the movement of materiel and individuals within and around potentially affected neighborhoods or defensible infrastructural conclusions regarding citywide pressures relieved by untying that knot. One hopes to find the promise of the Commission’s rigor kept with a cartography that clarifies costs and benefits for communities and outlines the terrain of interests and stakeholders. Justice in Design, however, offers a second illustration in which the knot of confusion, chaos, and constrained collection is rendered effortlessly resolved, a drawing that vaguely points to neighborhoods where new jail facilities are suggested within a flat, undifferentiated, neutral city.22 But for those communities and stakeholders, #WhereWeAre is not a city of abstracted ease. It is a complex political space in which they are now negotiating without a shared reference of options and effects, through which they are navigating without a map.

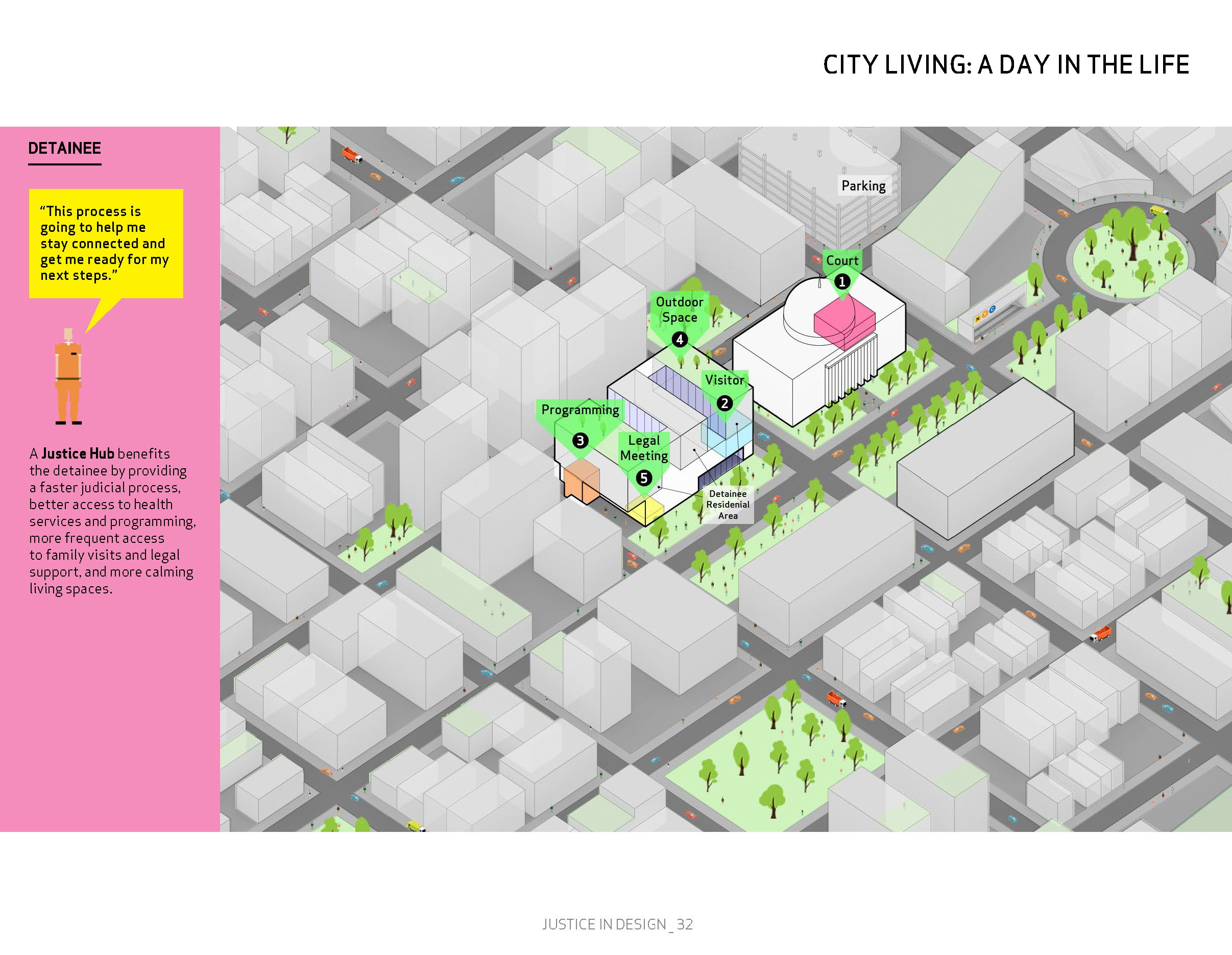

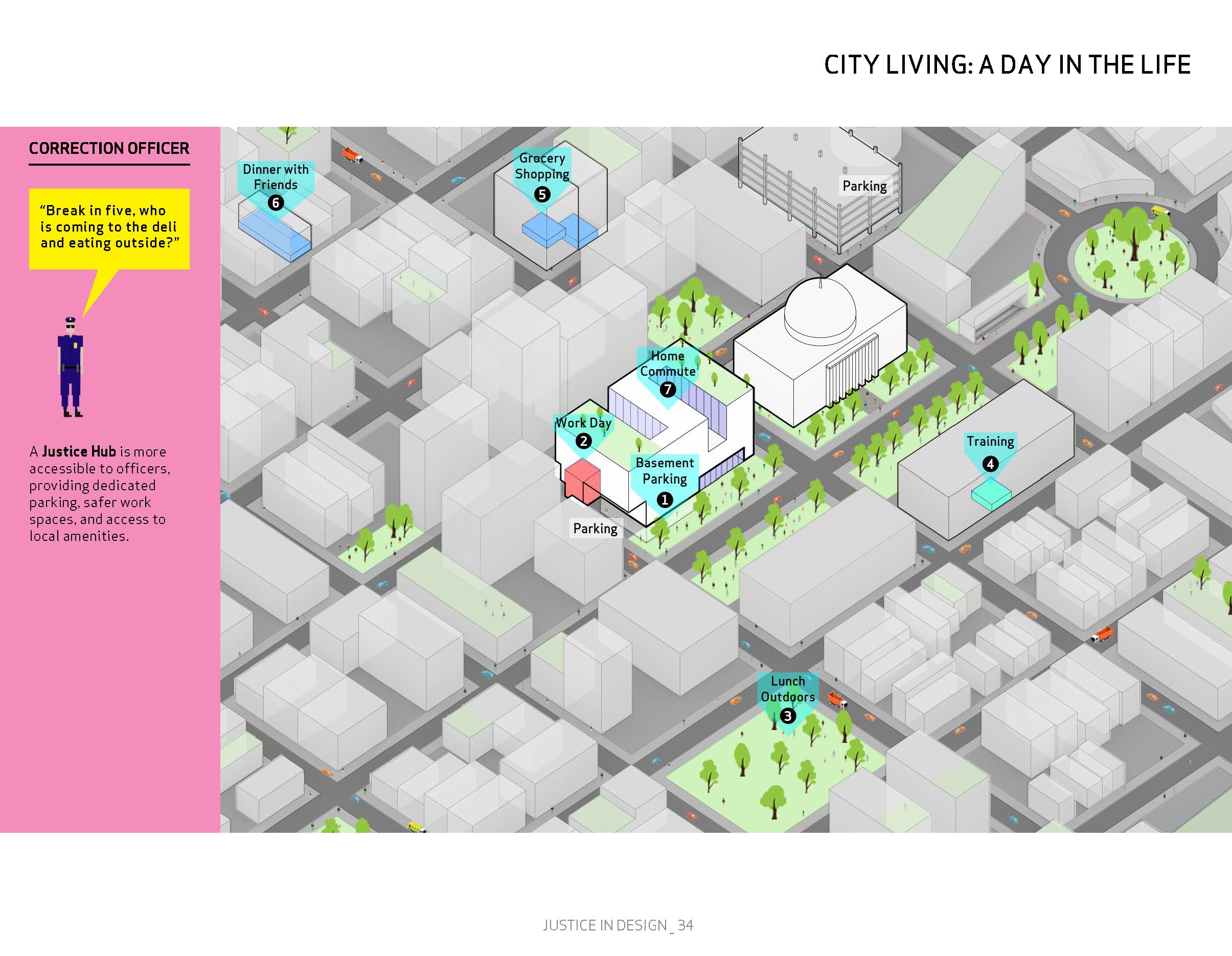

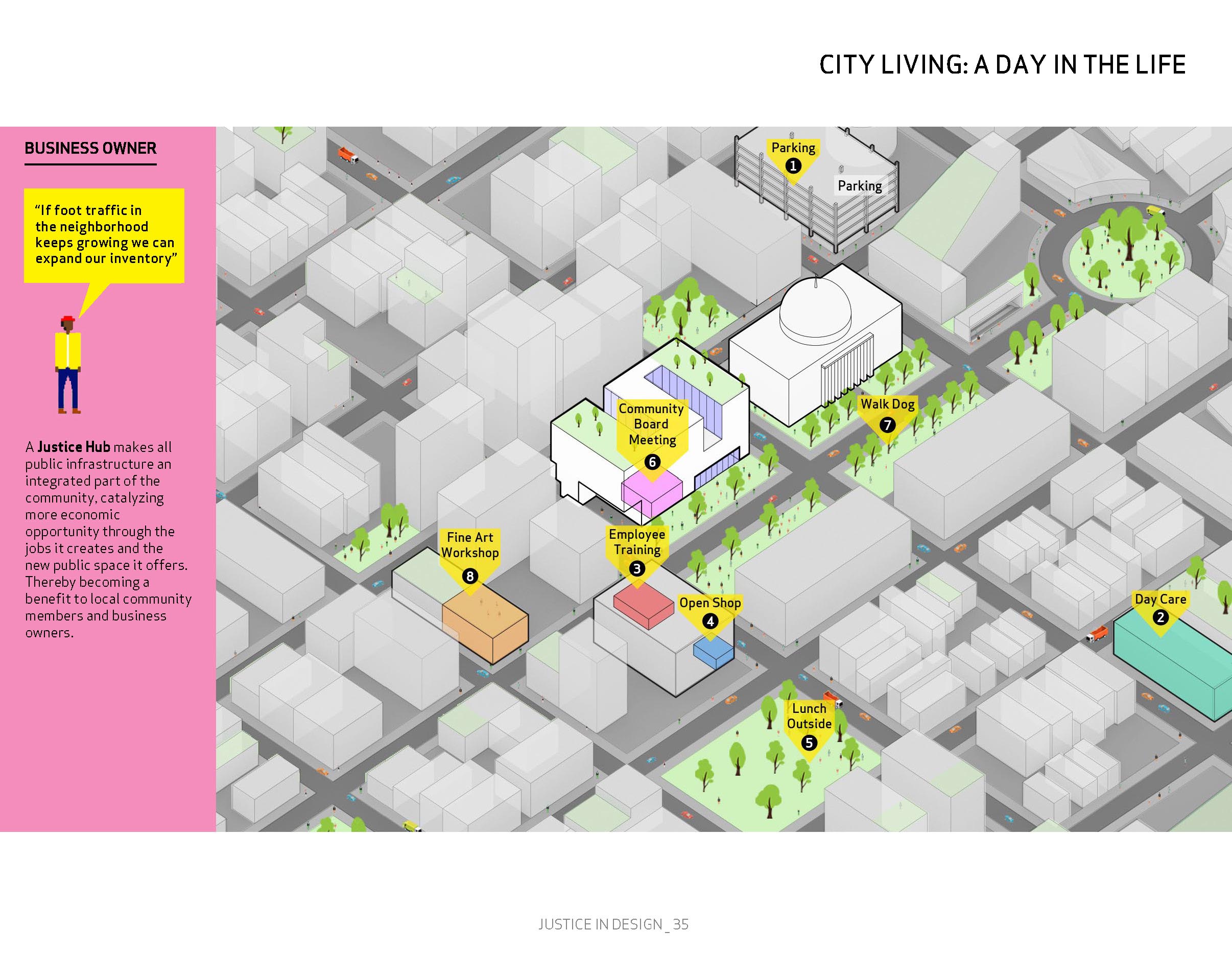

At the second scale (between new jails and their neighborhoods), a reading of the drawings should be framed by another of the Lippman report’s admirably lofty goals for New York #AfterRikers: “New jail designs should not merely provide benefits to offset the burden of having a jail in the neighborhood—they should aim to redefine the relationship between communities and the criminal justice system.”23 The Commission’s proposed cluster of criminal justice uses and related programming is rebranded by the designers as a “justice hub”—a central point within a network of services (i.e., a neighborhood) wherein a county jail promises multiple uses for multiple users as well as convenience, cost-saving, and community-connectivity by virtue of its proximity to the county courthouse and to other amenities.24 Certainly, the workshops and roundtables contributing to the Commission’s research and the Justice in Design project were a start toward redefining said relationship. The harder questions—in particular, those for which architects and planners offer specific professional expertise and thus carry specific professional responsibilities—include how new jail designs might reposition community members with respect to criminal justice systems, how the spatial relationships produced by design alternatives might create or constrict opportunities and social relations. Recalling the project’s mandate, these harder questions are precisely those the team was tasked with addressing, starting explicitly with the impacts jails have on communities, which, among others, presumably includes the communities surrounding new, proposed jails. These are questions requiring investigation through, for example, diagrammatic evaluation and measured (drawn) testing of the precedent case studies outlined in nonspatial terms by the Commission. The feasibility of clustered services, businesses, parks, and other amenities is readily testable surrounding the courthouses in each borough. Proximity is a necessary but insufficient criterion; the advantages, limitations, and burdens of particular locations and densities of these services—their catchments, connections, and carrying capacities—could be readily considered through visualization as analysis, through drawing as a mode of inquiry and site of interrogation. Each of these are scenarios the team might have readily illustrated, with impacts New Yorkers might then imagine, evaluate, and discuss together.

The drawings compiled in Justice in Design at this neighborhood scale stop short of evaluating equivalencies, problematizing positions, or simulating scenarios.25 They illustrate the combination of amenities and services, as well as their arrangement relative to one another, adhering to the nonspatial limits of the Commission’s findings without seizing the opportunity to investigate implications, assess feasibilities, compare alternatives, or ask new questions. The recommendations are rendered as generalized massings within an unnamed, generic site and surrounded by possible (some, admittedly hypothetical) programs.26 The complexity of an urbanism replete with diverse experiences is annulled by a compressed, frame-by-frame #DayInTheLife narrative that negates known differences, conflicts, and competitions between individuals and communities through their equivalent, atemporal, and separated representations. Here, one frame does not represent critical moments in that day—anticipated junctures of paths crossing, cooperating, or competing, nor the means by which the bottlenecks of Rikers might be avoided. Instead, each frame illustrates the availability of programs required or desired by a specific user throughout their imagined day, in isolation from the others. This strategy visualizes promises without complication and, as such, resembles advertisement over analysis. If the project was indeed a sales job, then selling a plan for new jails was always going to be difficult but never needed to be #AllOrNothing. Broadly and openly communicating the proposal and its implications could have created important, common references for negotiation. Representations of concurrence, disruption, limitation, and conflict were all opportunities to acknowledge trade-offs and frame local-level discussions. Further, they were opportunities to model a different professional role for architectural interventions that could shape the equity of criminal justice outcomes by arming various communities with divergent needs for those debates.

#DrawingIncarceration

Yet, the chance for such communicative influence was left on the table by not engaging the messier, contentious reality of drawing, designing, and evaluating the Commission’s recommendations in situ. The drawings do not function analytically nor describe the geography of corrections practices, its concomitant logistics, uneven spatial burdens, and diversity of impacts. And these decisions carry consequences: the equivalence established by omitting contextual consideration per neighborhood is now replicated in the City’s decision against evaluating each new proposed jail separately through its public review process—thereby diminishing communities’ localized efforts toward influencing specific outcomes.27 Rereading these drawings, one is confronted with representation as instrument and further compelled to ask how (as well as for whom and to what purpose) they were instrumentalized. The foreseeable consequences of the Justice in Design project lie in how its products would circulate, to whom they spoke, what messages they carried, and whether they would ultimately reinforce known, problematic, political processes.

If Justice in Design was simply meant as a more publicly accessible redelivery of the Lippman recommendations, then the Commission’s findings regarding public engagement and communication require greater consideration:

We know from hard experience that Not In My Backyard (NIMBY) opposition can pose a significant challenge for projects like these.

The Commission believes that the siting and planning process for any jail facility should be as transparent as possible. The City should create platforms for local residents and organizations to voice their concerns and feedback. It is in the City’s best interest to begin conversations with the community as early as possible, before the formal legal processes begin. Above all, imparting a sense of trust to the community is vital: the City should have regular and reliable contact with residents, and maintain a visible presence, particularly when facing challenging conversations or meetings.

Throughout the siting and planning process, the City should seek to educate the community on the full scope of issues related to Rikers Island, sharing data and other resources that can help address fears and dispel myths.28

This form of public engagement has not happened, and the Justice in Design team may not have known it would not.29 Still, we might learn from the role their work has served in its absence. Their illustrations have circulated as #VisualHashtags, as shorthand stand-ins for promises, as New York’s primary collective image of itself #AfterRikers—distracting, while real plans were made outside of public view. We might learn that none of us can afford to forgo that crucial, first-and-only chance to fulfill #AsEarlyAsPossible by beginning a public conversation in concrete terms, however contentious we know it will be. We might learn that our drawings could effectively facilitate inclusive debate but won’t without empowering communities with the “full scope of issues.” We might learn that shying away from guaranteed opposition provides cover for others, whether we intend it or not. Forfeiting any opportunity to problematize the urbanistic, sociospatial implications of a proposal means also forfeiting the chance to create platforms for advocacy by testing and presenting alternatives or to carry and maintain professional influence over a process so easily hijacked by power.

Perhaps, from #WhereWeAre amid the #SpatialPowerPlay of the City’s uneven debates, Justice in Design’s schematic, de-contextualized illustrations might be read differently. Now we have real plans for real sites within real communities devised through analysis that was not truly transparent, with outcomes dependent on mechanisms that are not sufficiently specific to those sites. Set against the (very limited) public-facing deliverables from Perkins Eastman—or Ricci Greene, a subcontracted firm on the team whose competent self-description explains that they “design normative environments that convey the message that normal behavior is expected in a setting that is secure”—the decision toward prototyping might serve a different end.30 The Justice in Design authors go to unusual lengths to ameliorate ethical concerns related to designing the systems through which individuals are detained prior to conviction. These include a “Values” appendix affirming that their process and its outcomes adhere to ethical norms, principles, and rules in both existing and proposed codes of conduct.31 The most immediately relevant is the Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR) proposed amendment to the Rules of the American Institute of Architects Ethics Code: “Members shall not design spaces intended for execution or for torture or other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, including prolonged solitary confinement.”32

Unpacking the extent to which any participation in the design of a carceral mechanism—including prototyping the eventual detention of nonviolent, unsentenced individuals carrying the presumption of innocence—violates either the letter or spirit of these codes is beyond the immediate scope of this discussion. But with this in mind, the generalized, prototypical illustration of a plan without situated, scalar consideration could be read as a tactical attempt to skirt the straightforward but thorny issues of professional ethics involved in #DrawingIncarceration. It was neither a fleshed-out plan nor a demonstrably implementable architectural proposal. By avoiding the on-the-ground actualities of sociopolitical context and physical site and by not offering a plan beyond the Lippman Commission’s findings, the design team could claim #PlausibleDeniability of any substantive ethical negligence or malfeasance. While a large portion of their project also illustrates interior program combinations and jail spaces, by all accounts they did not design a jail. Without clear or contextual analysis of a future jail’s impact on local conditions, they also did not design the means for its integration nor define its position within a neighborhood. That said, the diagrammatic lack of specificity is not an ethical loophole through which the designers might safely step beyond the constraints of codified norms and past the obligation of “beginning conversations with the community as early as possible.” Rather, it functions as an #EthicalSlipknot: it holds together the pieces of a plan until pulled onto the ground and into the city, where its generalized looseness gives way and quickly releases its designers from responsibility.

For whom, then, does this slipknot offer justice? The broader, hazier ethical questions are those anticipated by the Lippman Commission, those not delimited in building-related professional Codes, those concerned with whether outcomes are reached by just processes, and those in which #DrawingInPublic is implicated. Unsurprisingly, these are also questions of scale: the scales of specificity, of information, of intervention, of anticipatory action and practices of civic involvement. The drawings did not illustrate an implementable project; they were an implemented project. As such, they carry a set of ethical questions regarding their effects, use, and location within the city—including, for example, the completeness and clarity of the information shared, the impacts of their dissemination, their influence on decision-making, and their relationship to present and future participatory practices.

The questions left unanswered by this series of drawings are each matters of process, matters of publicness, and matters of pedagogy. Complex things around which publics should assemble and deliberate, in the Justice in Design report, became things reduced to a generic description of generic objects in equally generic places. The Justice in Design project constituted an opportunity for the City to learn together, constituted a thing around and in which substantive and difficult debate could have occurred. Of course, implementing this plan would have always been riddled with conflict, but we only had one shot at #AsEarlyAsPossible.33 And, whether by naivety or negligence, denying certain and unavoidable conflict through representational simplification—through #VisualHashtags—ultimately squandered the rarest of opportunities, undermined the efficacy of participatory practices, and degraded the possibility for collective discovery of (ever better) options. Insofar as they are shared, our drawings are always interventions. And that’s the thing we must learn (again).

-

The Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform (Lippman Commission), A More Just New York City, April 2, 2017, 92, link. ↩

-

Melissa Mark-Viverito, “More Justice: Speaker Mark Viverito’s 2016 State of the City Address, Remarks as Prepared for Delivery,” New York City Council, February 11, 2016, link; and David J. Goodman, “Melissa Mark-Viverito, Council Speaker, Vows to Pursue New Criminal Justice Reforms,” New York Times, February 11, 2016, link. ↩

-

On the evolution of the mayor’s position, note the changing headlines from the Times: Michael Schwirtz, “De Blasio to Unveil Plan for Rikers while Warning It ‘Will Not Be Easy,” New York Times, June 22, 2017, link; the New York Times Editorial Board, “Closing Rikers without a Road Map,” New York Times, April 3, 2017, link; and David J. Goodman, “De Blasio Says Idea of Closing Rikers Jail Complex Is Unrealistic,” New York Times, February 16, 2016, link. ↩

-

The Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform is usually referred to as the Lippman Commission, after its chair Honorable Jonathan Lippman. It is referred to as the Lippman Commission, or simply the Commission, throughout this text. The Commission released a follow-up report one year later, A More Just New York: One Year Forward, link.

Rikers Island is often described as the “world’s largest penal colony” (see, for example, Jennifer Wynn’s 2002 Inside Rikers: Stories from the World’s Largest Penal Colony). Some pertinent notes on Rikers and incarceration nomenclature: Rikers Island Correctional Facility comprises ten jail facilities operated by the New York City Department of Corrections. As jails, their primary function is detention: they mostly house individuals awaiting trial or sentencing—that is, “detained” individuals. Sentences served at Rikers are generally short (under twelve months), while longer sentences are spent at prisons. The distinction between jails or detention centers and prisons is worth keeping in mind during the discussion of Rikers’ present condition and possible future replacements. See NYC Department of Corrections, “Facilities Overview,” link, for a brief description of the Rikers Island facilities and other jails in the city. Thus, its status as a “penal colony” is more literary than literal, a reference to the collection and removal of individuals from several criminal justice jurisdictions to its island location.

↩ -

Lippman Commission, A More Just New York City, 2–3. ↩

-

Lippman Commission, A More Just New York City, 17. ↩

-

City of New York, Office of the Mayor, Smaller, Safer, Fairer: A Roadmap to Closing Rikers Island, June 22, 2017, link. ↩

-

Van Alen Institute and the Independent Commission for New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform (Lippman Commission), Justice in Design: Toward a Healthier and More Just New York City Jail System, July 13, 2017, link. ↩

-

It has also been seven months since portions of this text were prepared and delivered at the annual conference of the Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning during a special session on urban planning and incarceration. I could not have known the recent shape and contours of this process then, nor imagined some of the consequences of its early timeline. I am now following a moving target, knowingly writing with the benefit of hindsight. ↩

-

Audrey Wachs,“City Taps Perkins Eastman to Research Alternatives to Rikers,” Architect’s Newspaper, January 26, 2018, link. ↩

-

Communities, stakeholder groups, and politicians are divided on the future location(s) of incarceration in New York City. For just a few of many examples in the Bronx where a new facility is proposed, see: Ashley Southall, “In a Changing South Bronx, Residents See New Jail as Step Backward,” New York Times, April 2, 2018, link; Alex Mitchell, “Mott Haven Angered by Mayor’s Jail Plan, Lack of Support,” Bronx Times, March 18, 2018, link; Joe Hirsch, “New Jail Belongs Behind Courthouse, Says Councilman,” Mott Haven Herald, March 6, 2018, link; ED Garcia Conde, “Mayor de Blasio Foolishly Thinks South Bronx Residents Will Allow New Jail in Mott Haven So Easily,” Welcome to the Bronx, February 16, 2018; and Joe Hirsch, “City Announces Plans for New Jail in Mott Haven (Local Elected Officials Are Split on the Proposal),” Hunts Point Express, February 14, 2018, link.

For examples in Brooklyn, Queens, and Manhattan, where expanding existing detention centers is proposed, see: Daedalus Howell, “Rikers Island Closure Might Bring Inmates Downtown,” Correctional News, April 10, 2018, link; Ryan Kelley, “‘There Are No Advantages’ to Closing Rikers Island, Two Queens Officials Say at Prison Panel,” Queens Courier, March 9, 2018, link; and Mary Frost, “Plan to Enlarge and Redesign Brooklyn House of Detention Moves Forward with Council Deal,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 15, 2018, link.

Criticism of any plan to close Rikers persists while the plan is still subject to change. Some examples: Veronica LoPrimo, “Closing Rikers Island Would Be at the Expense of CO, Borough, and Inmate Safety,” Legal News (blog), MDASR, LLP, March 20, 2018, link; Thomas Cogan, “Rikers Island Shutdown Meeting Draws Large Crowd,” Queens Gazette, March 14, 2018, link; and James Ford, “City Says Closure of Rikers Facility This Summer Starts Shutdown of Entire Jail, but Criticism Ensues,” Pix11, January 2, 2018, link.

Throughout this process, Rikers remains a contentious battleground between Governor Cuomo and Mayor de Blasio: Reuven Blau,“Gov. Undermines Plan to Move Teenagers Off Rikers, City Says,” New York Daily News, April 17, 2018, link; Yoav Gonen, “DeBlasio Sues to Block Cuomo from Closing Rikers Facility,” New York Post, March 5, 2018, link; and Lisa Foderaro, “New York State May Move to Close Rikers Ahead of City’s 10-Year Timeline,” New York Times, February 14, 2018, link.

↩ -

(again, emphasis added) ↩

-

Regarding the public review process: Currently, the City plans to combine the four proposed jails into a single Uniform Land Use Review Process (ULURP) application. While this might expedite the process, it also combines (and potentially limits) the review of four distinct projects in similarly distinct conditions and neighborhoods. It may also delay the process for one or more facilities, due to contentious or problematic aspects of others. (Compare, for example, the public response in Brooklyn versus the Bronx. Cf. note 11.) We will have to wait and see.

Regarding stakeholder recognition: For example, Manhattan’s Community Board 3 is seeking a place on the City’s task force. The Manhattan Detention Complex, proposed for expansion, sits within Community District 1 but very near its border with District 3. The crux of their argument is in the unquantifiable scope of how we define “affected neighborhood.” Ed Litvak, “Community Board 3 Seeks Voice in Planning Chinatown Jail Expansion,” The Lo-Down, April 5, 2018, link. ↩ -

Van Alen Institute and Lippman Commission, Justice in Design, 26. ↩

-

Full Disclosure: I remain impressed and encouraged by the thoughtfulness and thoroughness of the Commission’s considerations as well as many of its conclusions. ↩

-

The mayoral plan set an early target for reducing the detained population: “our goal is to reduce the average daily jail population by 25 percent to 7,000 in the next five years” with an additional decrease (to 5,000) from further reduction in the overall crime rate. City of New York, Office of the Mayor, Smaller, Safer, Fairer, 8. The mean average daily population (ADP) of American jails was 253 individuals in 2015. Generally, jails are compared based on their jurisdiction size, and the largest category comprises jails with an ADP of 2,500 individuals or more. These had a mean ADP of 4,942 individuals in 2015. Todd D. Minton and Zhen Zeng, “Jail Inmates in 2015,” NCJ 250394 report, US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics (December 2016): 6. ↩

-

Minton and Zeng, “Jail Inmates in 2015,” 8. ↩

-

(This is an admittedly specialized theorization of scale I have been developing in recent work related to modes and implications of cartographic analysis. That said, its deployment here seems apt given the structure, content, and scope of the Justice in Design project.) ↩

-

The team’s “mandate” is summarized as five questions posed by the Lippman Commission and the Van Alen Institute. These also include “What site elements are important to include in the design of community-based jails?” and “How can we create jail designs that are more healthy, rehabilitative, and respectful?” See Van Alen Institute and Lippman Commission, Justice in Design, 6. ↩

-

Van Alen Institute and Lippman Commission,Justice in Design, 11. ↩

-

Beginning shortly after #AsEarlyAsPossible, the Urban Omnibus “The Location of Justice” series has published pieces addressing several of these opportunities and others listed throughout this text. See the earliest two, for example: Clara Dykstra and Stella Ioannidou,“After Arrest,” November 1, 2017, link; and Center for Spatial Research and Urban Omnibus, “Map: The Location of Justice,” November 1, 2017, link. ↩

-

Van Alen Institute and Lippman Commission,Justice in Design, 27. ↩

-

Lippman Commission, A More Just New York City, 92. ↩

-

Examples of requisite amenities and institutions cited in the proposal include parks, daycare centers, local businesses, and a gym. These are not all programs provided by the Department of Corrections. Most are expected components of a neighborhood and what the drawings call #CityLiving. ↩

-

Van Alen Institute and Lippman Commission, Justice in Design, 28–39. ↩

-

Cf. note 24. ↩

-

These consequences are less a matter of causality and more of cultural collocation and confounding. They arguably (and predictably) share a common cause. ↩

-

Lippman Commission, A More Just New York City, 92. ↩

-

It is impossible to offer references for material that does not exist. Suffice it to say that, at the time of writing, I cannot find Perkins Eastman’s report or analysis supporting their siting recommendations. Cf. notes 10, 11, 13, 30. ↩

-

The appendix includes two lists of “core values that would govern [the design team’s] process and outcomes” and a statement that their “values align with” the New York City Department of Design and Construction Excellence 2.0 Principles and the ADPSR proposed amendment. Van Alen Institute and Lippman Commission, Justice in Design, 57. ↩

-

Van Alen Institute and Lippman Commission, Justice in Design, 57. ↩

-

YOLO

Leah Meisterlin is assistant professor at Columbia University GSAPP. She also teaches the Building Justice Studio in Architecture and Urban Planning at Rikers Island through the Rikers Education Program at Columbia's Center for Justice.