Picture a commonplace situation: at a design studio review, an architect begins talking about how a space “feels” and waxing poetic about materials, lighting, and so on. He—let’s imagine this is an older, white male architect—imaginatively projects himself into a student’s project, strolls around, and describes the experience for everyone’s edification. His description is personal, and he makes no explicitly general claims, but the terms in which he frames his discourse imply an attempt at universality. The seasoned educator is trying to show the students how to enter into a certain relationship with architecture. The result is a feeling that he is attempting to foist the sole correct viewpoint upon them.

Following the architect, a historian/theorist enters the fray by noting the architect’s tendency to essentialize his own subject position. She complicates the discussion by emphasizing the ideological baggage that he has unwittingly brought into his explanation. Might those beautiful stairs look different if he were in a wheelchair? Might that generous “public space” feel differently if he were not white? Might that starkly minimal space have different connotations if he were poor?

In this scenario, the architect focuses on what he imagines to be his expertise—picturing, describing, and evaluating the details of a space—while the historian/theorist acts as a destabilizing force. The two are not disagreeing, exactly, but rather talking past each other. One provides orientation; the other, disorientation.

Historians and theorists in architecture schools today may well bristle at such divisions of intellectual labor (which, it might be added, are not as straightforward or universal as the forgoing sketch may imply). Are they invited to juries to act as curmudgeons? Should architects themselves be more critical? If our imagined architect is inhabiting a “phenomenological” mode and the historian/theorist is operating in the mode of critique, a plausible common ground might be something like “critical phenomenology.” Perhaps they should meet each other there to hash it out?

Issue 42 of Log, titled Disorienting Phenomenology, is an unexpected reappraisal of the phenomenological tradition in architecture and an invaluable overview of the critical phenomenology being undertaken today. It is unexpected in the way a major earthquake always is—everyone knows it’s coming, but this abstract knowledge doesn’t mitigate the unsettling thrill of the ground beginning to shake. The pressure has certainly been building up. A turn toward identity politics in the 1990s has, in the past two decades, often been localized in architecture as a tug-of-war between “critical” and “post-critical” theory that has left architects adrift when called upon to respond effectively to political urgencies—the #MeToo movement being only the most recent example. 1 How are architects to deal in a meaningful way not only with abuse and sexism but the range of prejudicial stereotypes—racialization, ableism, ageism—that they lean on, consciously or not? If Disorienting Phenomenology is a long-overdue reckoning, credit for its concrete manifestation in Log belongs to its editor, Bryan Norwood, who has a foot in several relevant worlds, having worked as an architect and studied philosophy before turning to architectural history and theory. This background gives Norwood a keen sense of what might be useful for architects today, as well as the role of theorists within design—not to add more philosophical baggage, but to “lighten the load, or at the very least redistribute it.” 2

It has been clear for decades now that this endeavor is necessary. Jorge Otero-Pailos’ Architecture’s Historical Turn: Phenomenology and the Rise of the Postmodern mapped the prehistory of this terrain in 2010, but because he wrote primarily as a scholar uncovering decades-old debates, it might be read as work of history with little capacity to challenge contemporary practice. 3 The conversation in Disorienting Phenomenology between Norwood and Otero-Pailos is revealing, particularly regarding the politics of phenomenology—how it was useful, many decades ago, in helping architects make the case for architecture as an academic discipline that belongs in research universities. Times have changed, and philosophy is perhaps not as esteemed as it once was. (Otero-Pailos notes that architects now borrow prestige from other fields—cognitive science, for example.) 4 Disorienting Phenomenology begins where Otero-Pailos leaves off: what is the use of phenomenology for architects today?

It’s a complicated topic, to be sure, and the strength of Disorienting Phenomenology is in the multiplicity of approaches in its nineteen essays. They are written mostly by scholars and theorists working within, or in frequent dialogue with, schools of architecture (Joseph Bedford, Kevin Berry, Jos Boys, Adrienne Brown, Charles L. Davis, Mark Jarzombek, Caroline A. Jones, Rachel McCann, Winifred Newman, Ginger Nolan, Bryan Norwood, Sun-Young Park, Benjamin M. Roth, David Theodore), though a few philosophers also contribute (Lisa Guenther, Bruce Janz, Dorothée Legrand, Dylan Trigg). Not all of these texts will be closely examined here, but the issue as a whole opens three angles of approach. First, upon noticing that phenomenology was sometimes misinterpreted by architects when they appropriated it in the 1950s through ’80s, several essays in Disorienting Phenomenology have returned to the classics—the greatest hits of phenomenology—and reread them. A second approach reflected in these texts is to notice how far the field of architecture has come since the heyday of phenomenology and to engage with current philosophical reassessments. We could call this “critical phenomenology.” A third approach would be to extend that critique still further, to the point of rejecting phenomenology altogether. This has been the status quo in recent years, so it is no surprise to find it in a few of the essays in Log, but there may be lessons to learn by reopening the case and deciding for ourselves.

I. Lessons from Phenomenology

Several of the writers in Disorienting Phenomenology offer a quick orientation to the history of phenomenology, and it is worth doing so here, as well. The classical tradition of phenomenology runs from around 1900 through the 1970s—a period that encompasses figures like Husserl, Heidegger, and Merleau-Ponty, though there were antecedents before them and lines of continuity to the present. The tradition’s discourses could be said to triangulate between existentialism, the psychology of perception (especially in Merleau-Ponty), and poetic philological musing (in Heidegger). Phenomenology’s entry into architecture, as Otero-Pailos has noted, occurred as architects in the 1950s and ’60s sought a way to frame their particular expertise in the context of the modern research university. Just as phenomenology in architecture became stereotyped as focusing on poignant materiality, atmospheric lighting, and high-craft detailing, the academic mood shifted more broadly toward identity politics, cultural studies, and respect for differences. Phenomenology in architecture looked hopelessly out of touch.

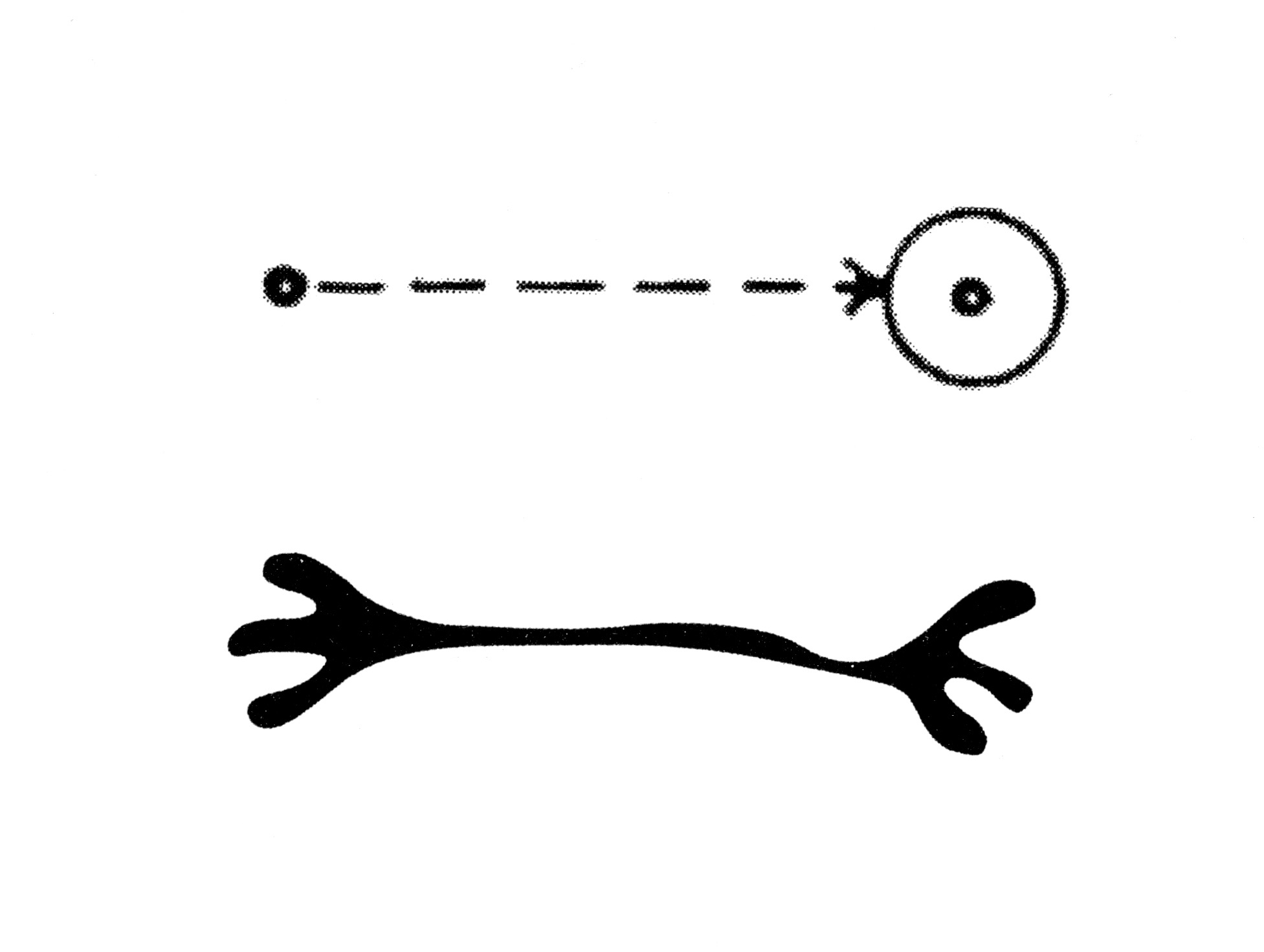

Only sporadically do the essays in Disorienting Phenomenology acknowledge the misinterpretations that architecture made of phenomenology and ask for reinterpretation. Minimizing this line of inquiry seems like an editorial strategy aimed at keeping the focus in the present rather than re-adjudicating decades-old intellectual politics. But Norwood seems to feel that a few problematic old concepts are worth rehashing, if only to set the stage for the criticism that appears in essays throughout the issue. The first is the most fundamental of all: the concept of “being.” Norwood’s editorial begins with a diagram from Christian Norberg-Schulz, author of some of the most popular books on phenomenology aimed at architects, and offers a critique via another diagram by Édouard Glissant:

Where Norberg-Schulz diagrams a “root identity” (visualized as a neat little circle) moving toward a “home” (another circle), Glissant represents “forced travel across the abyss of the Atlantic Ocean in the belly of a slave ship.” In place of the former diagram’s tidy circles and lines, the latter diagrams “being” as a sort of rope with frayed ends. Norwood describes the situation in architectural discourse:

The normativity of Norberg-Schulz’s root subjectivity has largely remained an assumed feature of architectural phenomenology…This ethical project is rooted in a presupposition of an ideal type of subject—one we can characterize as essentially colonizing, enlightened, white, straight, male, and able-bodied.

Norwood’s project, then, is to replace the normal with the strange and to challenge us to learn to live with disorientation. 5

If this is framed here as refuting the phenomenology of Norberg-Schulz that is so familiar to architects, it might also be seen as a return to some basic principles of phenomenology. Despite Heidegger’s many issues, we might glean fresh insight from even his most suspect concepts. 6 Take authenticity. In Heidegger’s words, “Authentic Being-one’s-Self does not rest upon an exceptional condition of the subject, a condition that has been detached from the ‘they’; it is rather an existential modification of the ‘they.’”7 This could be rephrased as a reminder that what is interesting about being is that it is both the product of its context and a unique “modification” of this context. As Norwood suggests, by diagramming the subject as a simple circle and thus conflating the universal everyday-self (the “they” in the quotation above) with the authentic-self, Norberg-Schulz leaves no room for variability in the way being orients itself in the world. Most of the essays in Disorienting Phenomenology wisely sidestep such explicit readings of suspect concepts, but glimmers of old but useful phenomenological insights are dotted throughout. Joseph Bedford perceptively argues—essentially following Heidegger—that phenomenological descriptions of being-in-the-world do not tell us how to be in the world. Many different forms of life are possible, none a priori better than the others. Bedford also summarizes Husserl’s intentions for phenomenology, suggesting their continuing relevance: “If human beings could only see that their reality was ontologically far deeper than they perceived it to be…they might regain a sense of wonder, and with it, spiritual openness and ethical reorientation.” 8

The first lesson of a return to phenomenology, then—and this seems rather basic—is that phenomenology is not really helpful as a diagram, but it is helpful as a way of prodding us to take ownership of our own being and to respect the singularity of others. Taking phenomenology as an invitation to universalize our own subjectivity—to assume we’re all normal—misses the point.

Norwood and Bedford also point out a second basic misreading of phenomenology that has to do with the stance toward technology. Unsurprisingly for a philosophy of the 1970s, a time of widespread techno-pessimism in the West, architects have read phenomenology as a critique of modern technology. 9 Technology, the story goes, interrupts being-in-the-world. Bedford shows that this should be understood as a social critique, carefully separating Heidegger’s problematic nostalgia from his phenomenological principle that technology is only one among many modes of being. Art also modifies being, as does architecture. Architects tended to take Heidegger’s critique of technology, which made sense in its historical context, as a basic feature of phenomenology. As Bedford puts it in his critique of Norberg-Schulz-esque diagrammatic phenomenology, “the mistake made by some architect-readers of phenomenology…is to assume that they are engaged in ontological analysis, when in fact they are reproducing a set of unacknowledged political and moral judgments about what is better or worse practice.” 10

The lesson here for architects is that the search for a root identity is problematic. Assuming a universal essence for humanity directly contradicts the existentialist notion that existence precedes essence and leads to even more problematic architectural pursuits, such as trying to substitute a world of poetic meaning for the supposedly “rational” world of technology. Thinking through phenomenology again (without Heidegger’s sometimes nativist social critique) demonstrates that being is always modified in various ways. While feeling “at home” may be a desirable mode of being for some, there is no reason architects cannot experiment with others. 11 Arguing for any one mode of being leaves the realm of phenomenology and enters the realm of ethics and the politics of morality. (Just to be clear: architects definitely should talk about ethics, but doing so through phenomenology can cloud the issue.)

A final point in Log’s return to classical phenomenology demonstrates an additional way in which architectural phenomenologists have misread the relationship of being with the world. As Kevin Berry writes in his contribution to Disorienting Phenomenology—which reads Heidegger’s discussion of tools alongside architects’ theories of creativity—Heidegger emphasizes that being is “involved in” the world rather than “contained in” it. However, the way architects have read phenomenology has twisted this relationship and imagined architecture as a sort of three-dimensional container in which human experience takes place. The latter, as Berry points out, is really a better description of the traditional Cartesian distinction between res extensa (“corporeal substance,” matter) and res cogitans (“mental substance,” cognition). Heidegger’s philosophy stands in direct opposition to this, explaining that humans are involved and invested in the world, not merely located within it. More specifically, we inhabit the world by using it. 12 The key philosophical term here is “readiness-to-hand,” the Heideggerian concept that describes the relationship between humans and equipment. (Readiness-to-hand, incidentally, is at the heart of Graham Harman’s neo-Heideggerian object-oriented ontology.) While working with a hammer, for instance, we do not think actively about the hammer itself; rather, we are involved in the act of hammering. Building on this, Berry makes the argument that design should not be seen as merely a formal exercise of solids and voids. Designers must also think of the architectural object as an “equipmental totality supporting various social performances.” He concludes by suggesting that “a Heideggerian architectural Phenomenology would require architects to learn to see space as something which human beings are involved in, not contained in.” 13

As Disorienting Phenomenology shows, it is telling that a philosophy that was designed to strip away clichés—this was Husserl’s intention—was used to bolster among architects the persistent cliché of the universal subject. 14 Maybe this was inevitable, seeing as how architects are generally in the business of designing things for other people that they can only know in a limited way. But what if we sought to create better clichés? To do this we might follow the path Norwood points out and create a host of non-normative “phenomenologies”: Ian Bogost offers “alien phenomenology,” Sara Ahmed offers “queer phenomenology,” and so on. We could experiment with different modes of being or appreciate the critical potential of “not fitting,” as Jos Boys argues in her essay. 15 This is also a lesson from old-school phenomenology. In the spirit of Husserl, phenomenology is not about returning to origins, but strange-making—alienating our own perception and paying close attention to how existence works.

II. Toward a Critical Phenomenology

Whether or not architects choose to reread the classics of phenomenology, they might still rethink the methods of phenomenological analysis. Disorienting Phenomenology suggests this direction in a text by Dorothée Legrand, which argues that the fault in phenomenology lies specifically in the act of reduction that abstracts subjectivity into transcendental identity. 16 Legrand describes the act of “bracketing” or suspending judgment about the nature of the world (what Husserl called “epoché”) while refusing to “reduce” the subject of the experience to a generalized transcendental identity. What this “epoché without reduction” entails is to give up trying to find some primitive root identity beyond our own identity. This intrinsically makes sense: when we think about experiences, we don’t usually imagine them from the perspective of some universal human subject—we usually have ourselves very much in mind. But proposing epoché without reduction is in fact a big move with respect to phenomenology, as for Husserl, epoché and reduction are part of the same process.

Legrand demonstrates why epoché with reduction is problematic by showing how Husserl twisted the definition of epoché from its original Greek meaning. Epoché was originally understood as the act of “refusing any form of reduction of multiplicity of philosophical systems to one truth.” Following epoché with reduction is therefore absurd. Furthermore, while performing epoché, Husserl “does not only, by the suspensive gesture, detach himself from any presence of the world, but also, by the reductive gesture, does not consider the world at all, but only his experience of the world.” 17 Husserl writes: “The total field of possible research is indicated by a single word: that is, the world.” 18 It is clear, as Mark Jarzombek points out, that “world, as [Husserl] states polemically in the sentence, is a ‘single word.’ It is also singular; world, not worlds.” 19 In other words, the world gets reduced to a single experience—to a root, an original foundation, a home. In our desire for explanation and meaning, epoché remains incomplete, and the opportunity to think beyond our subjectively constructed world gets lost. In his contribution to the issue, Benjamin M. Roth writes about this elegantly in relation to nihilism:

The project of an ethical architecture…will only reinforce false assumptions about where meaning comes from, thus leaving us mired in nihilism…Amidst so much architecture trying to make us feel at home in the world, perhaps what we need is an architecture that helps us achieve meaninglessness…If we take the task of achieving meaninglessness seriously, we have to be willing to descend into the valley of nihilism without knowing if there is anything on the other side. 20

Perhaps the lesson here is not simply that architects have missed the potentials of phenomenology but that many thinkers—even phenomenologists!—have taken it in sterile directions. This by no means discredits phenomenology. Disorienting Phenomenology shows that phenomenological concepts should be considered low-hanging fruit—years of neglect mean that pursuing their insights can easily yield substantial intellectual rewards. Philosophers are already onto this. While embracing the unfamiliar is a central move of critical phenomenology, it also resonates with important questions in philosophy more broadly. Roth borrows the notion of “achieving meaninglessness,” for example, from Simon Critchley, who is a philosopher of ethics and politics.

Of all the concepts Disorienting Phenomenology asks architects to rethink, epoché without reduction may be the most fecund. The maxim is simple: examine your own experience, and don’t jump to conclusions about its meaning or project it onto others. This ought to be a useful intellectual tool for—in the provocative phrase of Norwood—allowing us to “provincialize our own embodiment.” 21 This is in line not only with current directions in architecture but also with contemporary social justice movements of all types.

III. Rejecting Phenomenology

The foregoing may seem fruitful, but in the end, architects might make the informed decision that reinterpreting or redefining phenomenology is not the best path to take—and a few of the authors in Disorienting Phenomenology present arguments for doing away with phenomenology entirely. One reason today’s architects might want to put phenomenology to rest was suggested at the outset: in generalizing from the first-person perspective, it unsurprisingly often ends in a tyranny of the singular and personal over the multiple and social. Ginger Nolan points out that there is something “fascist-like” about architectural phenomenology’s disinterested attitude toward history. Stories of mythical origins have lured many architects into projects to “purify” architecture. Nolan describes how Laugier’s primitive hut, for instance, is not a revival of history but an attempt to “obliterate the historicalness of humans by postulating the meta-historicalness of architecture.” She suggests that something in the very structure of phenomenology tends to merge a primordial origin with the present, without the intervention of history. 22

It is no surprise, then, that the most historical essay in Disorienting Phenomenology brings us furthest from phenomenological methods. Sun-Young Park’s fascinating discussion of institutions for the blind in nineteenth-century Paris details a concrete example of contradictory agendas in early modernism. While these institutions aspired to “the normalized subject” and expressed “faith in the therapeutic power of architecture,” they also began with “the premise of embodied difference.” Early phenomenological thinking was enlisted to help shape “model citizens,” but architects were nevertheless sensitive and accommodating to bodily differences. Because Park’s discussion takes place within the methodological frame of historical ontology, there is little to conclude aside from the fact that nineteenth-century architects saw things very differently than twentieth-century phenomenologists—and very differently again from architects today. 23

Park’s essay brings us close to the subject matter of the most-known theorist of historical ontology, so an anecdote about Michel Foucault may be instructive while sorting out places for phenomenology and history in architecture. One of Foucault’s most famous aphorisms is that “nothing in man—not even his body—is sufficiently stable to serve as the basis for self-recognition or for understanding other men.” 24 This was a direct attack on the very terms of phenomenology: perception, experience, and embodiment are all socially constructed, Foucault argued. But there’s a caveat. As Hubert Dreyfus and Paul Rabinow helpfully pointed out in the early 1980s, Foucault was not being entirely serious. Of course people generally have two arms and two legs, they concede—and so phenomenologists can indeed make some valid generalizations. But Foucault’s point was that this is a dreary place to start a theoretical investigation. If we start with “experience” or “embodiment,” we preload the conversation in a way that makes it difficult to take a multiplicity of viewpoints and bodies into consideration. 25

Foucault’s own methods of historiography—“archaeology” and “genealogy”—can also devolve into clichés, of course. It’s easy to lampoon historians: everything “depends on the context” and everything is always “more complicated.” The cliché of the historian is that they can never say anything general or abstract.

Rather than arguing the relative merits of phenomenology and historiography, however, Disorienting Phenomenology points toward a problem that is common to both: normalization. The solution is also shared between the two methods. Defenders of Foucault often turn to an essay—“What Is Enlightenment?”—in which he insists that the “attitude” of modernity requires a continual performance of critique—resisting normalization and living with disorientation. This is the underlying theme of most of the essays in Disorienting Phenomenology, and it is both a worthy intellectual challenge and a necessary response to today’s pressing issues.

In our assessment of intellectual methods, it is worth acknowledging that phenomenology has the benefit of being clearly oriented to the present—to life as we live it. Framed in numerous ways through its myriad essays, Disorienting Phenomenology offers an intellectual approach that finally seems up to the task of equipping today’s architects to understand and address the intersection of differences and stereotypes at which they operate. Let’s stop universalizing our own experiences and quickly jumping to imagine idealized “users.” While “epoché without reduction” may never catch on, learning to “live with disorientation” and “provincialize our own embodiment” are methodological shorthands designed to encourage architects to consider differences of gender, ability, skin color, and so on, in their work. So with the holiday season approaching, a copy of Log 42—if you can track one down—would make an excellent present for any architect you know in need of productive disorientation.

-

Stella Lee, “Why Doesn’t Architecture Care About Sexual Harassment?” the New York Times, October 12, 2018, link. ↩

-

Bryan E. Norwood, “Disorienting Phenomenology,” Log 42 (2018): 11. ↩

-

Jorge Otero-Pailos, Architecture’s Historical Turn: Phenomenology and the Rise of the Postmodern (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010). ↩

-

Bryan E. Norwood and Jorge Otero-Pailos, “An Interview with Jorge Otero-Pailos,” Log 42 (2018): 137–144. ↩

-

Norwood, “Disorienting Phenomenology,” 12. ↩

-

One place to start: Peter E. Gordon, “Heidegger in Black,” the New York Review of Books, October 9, 2014, link. ↩

-

Martin Heidegger, Being and Time (New York: Harper, 1994), 168. ↩

-

Joseph Bedford, “Towards Rethinking the Politics of Phenomenology in Architecture,” Log 42 (2018): 182. ↩

-

The mood shift from techno-optimism to techno-pessimism is perhaps easiest to see in the art world. The sharp upward then downward trajectory of Jack Burnham’s career as an art theorist, with his 1970 exhibition Software at the inflection point, is instructive. See Luke Skrebowski, “All Systems Go: Recovering Hans Haacke’s Systems Art,” Grey Room 30 (2008). ↩

-

Bedford, “Towards Rethinking the Politics of Phenomenology in Architecture,” 181. ↩

-

Peter Eisenman famously argued this point against Christopher Alexander in 1983: “Contrasting Concepts of Harmony in Architecture,” Lotus International 40 (1983). ↩

-

Kevin Berry, “Heidegger and the Architecture of Projective Involvement,” Log 42 (2018): 111–113. ↩

-

Berry, “Heidegger and the Architecture of Projective Involvement,” 115. ↩

-

Edmund Husserl, Ideas: General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology (London: Routledge, 2012), 59–60. Here, Husserl describes epoché as an act of suspending all judgment, in this way negating clichés and assumptions about the world. ↩

-

Jos Boys, “Cripping Spaces? On Dis/abling Phenomenology in Architecture,” Log 42 (2018): 55. ↩

-

Dorothée Legrand, “At Home in the World? Suspending the Reduction,” Log 42 (2018): 23–26. ↩

-

Legrand, “At Home in the World? Suspending the Reduction,” 24. ↩

-

Edmund Husserl, Ideas, General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology, translated by W. R. Boyce Gibson (New York: Collier Books, 1962), 42. ↩

-

Mark Jarzombek, “Husserl and the Problem of Worldliness,” Log 42 (2018): 73. ↩

-

Benjamin M. Roth, “The Abetment of Nihilism: Architectural Phenomenology’s Ethical Project,” Log 42 (2018): 135. ↩

-

Norwood, “Disorienting Phenomenology,” 22. ↩

-

Ginger Nolan, “Architecture’s Death Drive: The Primitive Hut Against History,” Log 42 (2018): 91–102. ↩

-

Sun-Young Park, “Designing for Disability in 19th-Century Paris,” Log 42 (2018): 81–90. ↩

-

Michel Foucault, “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History,” Foucault Reader (New York: Pantheon, 1984), 87–88. ↩

-

Hubert Dreyfus and Paul Rabinow, Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982). ↩

Matthew Allen is a PhD candidate at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and a lecturer at the University of Toronto. His research focuses on the history and theories of computation and aesthetics in twentieth-century architecture.

Kian Hosseinnia studies architecture and philosophy at the University of Toronto and operates a collaborative design practice that creates small-scale insertions in neglected spaces within dense urban fabrics.