In that place, where they tore the nightshade and blackberry patches from their roots to make room for the Medallion City Golf Course, there was once a neighborhood. It stood in the hills above the valley town of Medallion and spread all the way to the river. It is called the suburbs now, but when black people lived there it was called the Bottom.

— Toni Morrison, Sula, 19731

The Bottom reflects a colloquial term used to describe black communities within or surrounding larger—visibly segregated—urban areas. An eponym that either describes the presence of dark marshy soil or land of poor value, the term emerged in the twentieth century to illustrate both where black people lived and their social standing in American society.2 With these characteristics and implications, the Bottom as an urban typology possesses a distinct vulnerability when confronted with American planning protocols and inequitable power structures that deprioritize—and destroy—the presence and importance of these communities.

At its core, the Bottom is a neighborhood, with neighborhood things, like homes, shops, families, schools, and churches. Throughout American history, the Bottom has faced particular scrutiny because of its concentrated black population, which was so often coupled with insufficient and inferior opportunities for housing, employment, and high quality of life. The Bottom does not exist in one place but in every place across the United States that shares these characteristics.

The Bottom has no origination date as it varied across the country, becoming more prevalent as acts of racialized violence increased. Many Bottoms, particularly in the Northeast and Midwest, formed during the Great Migration, the exodus of six million Blacks out of the rural South between 1916 and 1970.3 While emerging urban industrial opportunities in the Northeast and Midwest catalyzed the mass movement, the migration was significantly triggered by the enforcement of race-based segregationist law and the rise of white supremacist groups and lynching in the South. Lynching—premeditated vigilante-style executions—were used to assert white power and black powerlessness under the law.4 Lynching victims were often hanged, shot, burned alive, tortured, and dismembered with body parts kept as souvenirs.5 They were organized as family events, many of which were documented and published as postcards.6 According to the Tuskegee Institute, 4,743 people were lynched between 1882 and 1968, including 3,446 blacks and 1,297 whites. More than 73 percent of all lynching in the post–Civil War period occurred in Southern states, like Georgia and Texas.7 The cruel terrorism of blacks and disenfranchisement under the law influenced the Great Migration to northeastern and midwestern states.

While the Bottom presents no defined geographic location, it became more apparent as race-based segregation divided housing options and neighborhood compositions. While the northeastern and midwestern states offered employment outside of the agrarian economy of the South, blacks still faced severe discrimination, especially in housing. Redlining was a systematic exclusionary practice identifying geographic zones that banks used to refuse financial services to blacks, either toward a home mortgage or a business venture.8 These racist policies were particularly used to eliminate any racial integration of neighborhoods and to refuse service to black clients. This perpetuated public disinvestment and local economic stagnation, directly contributing to the degradation of the housing and other public services and goods. This strategy depreciated the value of the neighborhoods to which blacks were confined.9

Anti-black campaigns helped fortify this process. Commonly, propaganda and realty specialists promised white residents plummeting land values and a jolt of crime if black residents moved in. Covenants, legal agreements to deny sale to other ethnic groups, and blockbusting, a deceptive tactic used to buy and sell homes through xenophobia, were employed to keep neighborhoods racially segregated.10 Blacks had limited housing options, which quarantined them in undesirable areas. In pursuing better housing opportunities, blacks were often met with protests, angry mobs, and frequent conflicts with police and anti-black vigilantes. By the mid-1920s, the second rise of the Ku Klux Klan had emerged in northeastern and midwestern urban areas to actively resist racial integration and diversity, its densest per capita membership in Indiana.11 Nearly half of Michigan’s eighty thousand Klansmen by 1930 lived in Detroit, inciting and continuing anti-black propaganda and violence.12

So blacks lived in the Bottom, the first black American urban landscape. For many, the Bottom became a thriving, aspirational clean slate that served as a refuge and platform for achievement within the oppressive anti-black system. Emerging from the confines of low-quality housing and infrastructure came growing businesses and professionals, slowly building the wealth and financial security blacks did not have under the crushing hand of chattel slavery, Black Codes, and Jim Crow segregation. Out of the Bottom came America’s black firsts: doctors, lawyers, teachers and professors, dentists, small manufacturers, politicians, and community leaders.13 Black Wall Street emerged throughout the country with premier financial services to cover the areas redlining omitted.14 The Bottom, in places like New Orleans, Harlem, and Chicago, became hotbeds of culture, giving rise to literary and musical movements like jazz, soul, and blues that would come to shape American identity. While the Bottom served as a promised land to some, it was not perfect. There was organized crime, trafficking, corruption, and other illicit activities.15 Violence ensued, garnering notorious reputations for hardcore street life and gang culture in some areas.16 The Bottom possessed positive and negative qualities of urban life, as was experienced in areas outside of the Bottom as well.

More importantly, however, the Bottom occupied space, constituting a vernacular landscape that was shaped by America’s largest marginalized group and maintained by oppressive and separatist policies and practices. With an increasingly derogatory meaning for those living outside it, the Bottom had a presence on the redlined portions of zoning maps although it presented a positive identity for blacks that lived there. It represented an opportunity for ownership, a privilege with which black Americans had little history, even with their own bodies. The Bottom offered businesses and home life that was directly connected to place. The municipal neglect and disinvestment in the Bottom offered authorship and stewardship that truly made the place a black American urban landscape, indicative of the black American experience.

However, the Bottom emerged out of a social vulnerability; the prospect of its tenancy was still a risk. For those that looked on from the outside, the Bottom was a manifestation of all the social ills that plagued urban society. It was considered more of a ghetto than an enclave and was therefore redefined to mean the bottom of American society. As early as the 1930s, these communities were labeled and advertised as “slums” and “blighted,” a contagious infection to the larger urban fabric.17 Even as some residents managed to survive the economic ills of the Great Depression while combatting poor optics and pressures, leaders like Robert Moses maintained that “slums” were “the obstacles in the way of healthy and uninterrupted progress.”18 Despite its resilience, for many the Bottom represented a regression in modern society.

So-called reform of the Bottom, therefore, was inevitable and came largely under the guise of Urban Renewal and the Federal Highway Act of 1956. Urban renewal is a process in which real property is purchased or taken through eminent domain by a municipal authority, razed, and then redistributed to developers to devote to other uses.19 In the mid-twentieth century, many cities in the United States did not have the quality housing stock needed to support their brimming populations, especially with influxes in migration. In order to address these shortages, municipal development authorities and local planning departments identified areas of low land value to destroy and rebuild. Concurrently, The Federal Highway Act of 1956 offered federal funds to build highways across the country to support the rise in vehicular transportation and associated lifestyles.20 Investigating areas of low land values, these agencies took a quick review of the local bank’s redlining maps to identify the perfect location. Habitually, they chose the Bottom.

And this is why, in most cases, the Bottom possesses a distinct vulnerability. These neighborhood typologies have been razed and replaced with highways, modular housing, or parks through municipal effort and support in an attempt to emphasize and exert power, order, and efficiency. Detroit and New York City both offer compelling examples of the razing of Bottoms for a public infrastructure that imposed sacrifice on a black American urban landscape and experience.

Detroit

Detroit’s Bottom was called, in fact, Black Bottom and was a predominantly black neighborhood that emerged in the early 1900s.21 Similar to others, Black Bottom in Detroit was formed in response to racially discriminatory housing practices.22 Regardless, Black Bottom rose to become a thriving neighborhood, with strong commercial corridors along Hastings and Saint Antoine Streets.23 By 1942, the Detroit Urban League reported that Black Bottom had a laundry list of business owners and professionals including 151 physicians, 140 social workers, 85 lawyers, 71 beauty shops, 57 restaurants, 36 dentists, 30 drugstores, 25 barbershops, 25 dressmakers and shops, 20 hotels, 15 fish and poultry markets, 10 hospitals, 10 electricians, 9 insurance companies, 7 building contractors, 5 flower shops, 2 bondsmen, and 2 dairy distributors.24 Black Bottom was also nationally famous for its music scene: Duke Ellington, Pearl Bailey, Ella Fitzgerald, and Count Basie regularly performed in its bars and clubs. In fact, Aretha Franklin’s father, the Reverend C. L. Franklin, founded the New Bethel Baptist Church on Hastings Street.

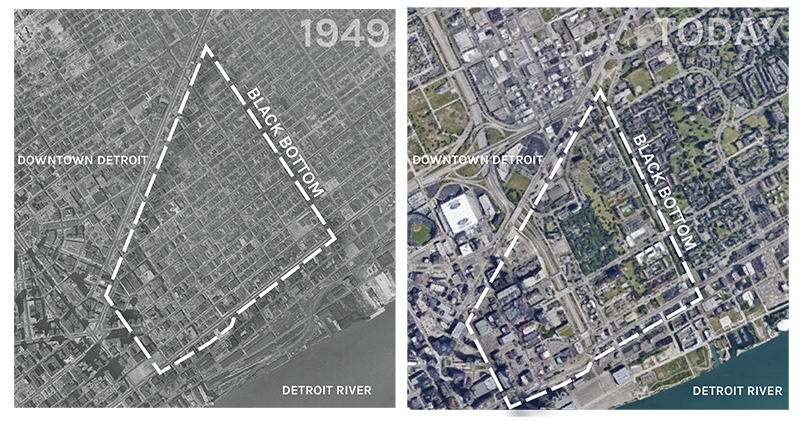

While successful in many ways, the area was crowded, and housing quality declined. Race riots and incited conflicts with the police contributed to the area’s overall dilapidation.25 By the 1950s, many cities across the United States had adopted major urban renewal projects to eradicate severe living conditions in American “slums.” In 1951, Mayor Edward Jeffries’ slated Black Bottom as eligible for slum clearance and planned to build I-375, a local interstate highway designed to loop around Detroit’s Downtown.

How could Black Bottom be a slum when it was a burgeoning neighborhood adjacent to downtown? At the time, Detroit’s population had reached its peak at 1.86 million people; the city was a center of economic growth with plenty of resources to support its various communities. Black Bottom could have been strengthened and reinforced as a unique urban space, but by 1954, it was completely razed. By 1967, seventy-eight acres had been cleared to make way for I-375, and Lafayette Park, a new mixed-income planned community featuring Mies van der Rohe homes and high-rises.26

The replacement of Black Bottom with Lafayette Park marked a significant change in the urban landscape. The realized design for Lafayette Park offered order, homogeneity, and large green spaces that teleported the community away from Detroit and away from its roots in Black Bottom. The bustle of urban street life and the shuffling of businesses were replaced with a luxurious rural-like bedroom community. The highway split the area from Detroit’s downtown, creating a physical and visual barrier from the city’s core. Most notably, the interactive street level was reduced to bucolic walkways, eliminating any sense of community and gathering. The porch culture and early notions of “eyes on the street” in dense low-rise housing dissolved into high views of a distant skyline.27 The black presence was physically and figuratively eliminated. In fact, the imposed urban landscape neutralized the black American urban landscape that preceded it, paving over black experience, identity, and endurance. The slab-shaped buildings and the vastness of the accompanying green spaces offered themselves as a clean slate, with the purpose of eliminating any remnant of Black Bottom. It seems that place, when associated with marginalized groups, is not considered a place at all but a space open and available for new occupancy. The marginalized cannot truly occupy space if they also do not occupy power.

New York City

This is not a new story, or even one confined to the twentieth century. Seneca Village was a small settlement of free black landowners in Manhattan established in 1825. The area, incorporating about five acres, would have been located on the Upper West Side today between Eighty-Second and Eighty-Seventh Streets at Seventh and Eighth Avenues.28

Seneca Village—the Bottom—was a neighborhood, with neighborhood things, like homes, shops, families, schools, and churches. While chattel slavery was still an economic engine for the United States, Seneca Village offered one of the country’s first free towns where freed blacks, and other alienated ethnic groups like the Irish and Germans, could own land and resist the oppression they endured in many other places in New York City.29 At its peak, Seneca Village had over 350 residents and was a thriving small farm town.30

In the mid-nineteenth century, sociologists and other thought leaders promoted new and greener ways to contend with the gritty urban landscape that emerged from industrialization and overpopulation. 31 Garden cities and the importance of public parks became central to the conversation to improve poor urban health.32 Designed public spaces idealized a social freedom that provided a leveling field of interaction between people of different classes.33 As New York City embraced these ideals for a major green space, the Common Council looked for locations for the proposed Central Park. They chose to expand to Seneca Village.

As the campaign to create Central Park moved forward, advocates and media outlets sensationalized Seneca Village as a “shantytown” and the residents as “squatters, vagabonds, and scoundrels.”34 For two years, Seneca Village residents resisted the police and petitioned the courts to save their homes, churches, and schools, but this was largely unsuccessful, as blacks were not recognized as citizens under the law.35 Finally, by 1857, the New York City government leveraged eminent domain to evict all of the Village residents and usurp its private property. Seneca Village was completely razed within the year, and the design and construction of Central Park started almost immediately. Central Park was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Faux, a prominent pair of designers that went on to build other large-scale public spaces across the United States. The realized design for Central Park offered diversity in topography and smooth transitions between the bucolic and the naturalistic landscape. Where Seneca Village was, there is now a 106-acre reservoir, the infamous Great Lawn, and other smaller playgrounds. To commemorate Seneca Village, there is a small green sign.

The replacement of Seneca Village with Central Park set a precedent for how black American urban landscapes would be incorporated into the larger urban fabric as they continued to sprout across the nation. In short: they wouldn’t be. The rhetoric behind razing black American urban landscapes prevails through time and resonates from a historic anti-black perspective that prevents black-grown urban areas from reaching full fruition. In Central Park, the black presence was physically and figuratively eliminated. The parkland buried the foundations of a growing urban fabric and replaced it with an amenity that the former inhabitants could not enjoy. Without power, the residents of Seneca Village could not successfully resist the municipal and police powers that forcibly removed them from the area. Without real property ownership or enfranchisement, the black population could not successfully access the protections enshrined for others in the law.

The histories of Black Bottom and Seneca Village illustrate a significant message that requires more attention in the urban planning world today: black American urban landscapes are especially susceptible to destruction because of the success of anti-black sentiment that pollutes planning policy and thought. This culture creates a long history of governmental facilitation of—and planning for—displacing blacks from the places they established. As a continuously socially and economically marginalized group, blacks and the spaces they occupy are vulnerable and often considered ripe for the taking.

In the cry against gentrification in neighborhoods that represent contemporary Bottoms—Inglewood, Harlem, West Philadelphia—it is important to address the long history this country has of destroying black urban landscapes. The socio-economic disparities contained within the binary of whiteness and blackness present significant challenges in identifying places and spaces that qualify for conservation or redefinition. When those worthy spaces are decided upon, as they have been for the last several centuries, the black vernacular landscape is replaced with elements that continue to stratify and segregate—through highways, high-rent apartments, and large green spaces. The missing root here is power. A shift in social understanding and an investment in economic development and empowerment can potentially change the fate of Bottoms across the country.

As cities gentrify and rebuild, local planning agencies and development authorities must revisit the histories of the Bottom, just as they must incorporate inclusive strategies that elevate marginalized residents into key players in the turnover of their neighborhoods. Providing local access to capital and supporting models that present existing residents as leaders allow neighborhoods to transform as a continuation of the existing black vernacular landscape, and not with a different, separatist language. Power honors the place and has the potential to resist the history of forcible displacement of blacks in American urban areas. These black American urban landscapes—the Bottoms—are neighborhoods first, with many wonderful neighborhood things.

-

Toni Morrison, Sula (New York: New American Library, 1973), 1. ↩

-

Tony Gonzalez. “Curious Nashville: How The ‘Black Bottom’ Neighborhood Got Its Name—And Lost It,” Nashville Public Radio, June 17, 2016, link. ↩

-

Ron Grossman, “Commentary: The Great Migration: For Southern blacks, Chicago Offered Jobs—But Not the Warmest Welcome from Whites,” Chicago Tribune, April 12, 2018, link. ↩

-

J. R. Moehringer, “An Obsessive Quest to Make People See,” Los Angeles Times, August 27, 2000, link. ↩

-

Moehringer, “An Obsessive Quest to Make People See.” ↩

-

Moehringer, “An Obsessive Quest to Make People See.” ↩

-

Jared McWilliams, “Lynching, Whites, and Negroes,” Tuskegee Institute, April 24, 2018, link. ↩

-

Tracy Jan, “Redlining Was Banned 50 Years Ago. It’s Still Hurting Minorities Today,” Washington Post, March 28, 2018, link. ↩

-

Jan, “Redlining Was Banned 50 Years Ago. It’s Still Hurting Minorities Today.” ↩

-

Jan, “Redlining Was Banned 50 Years Ago. It’s Still Hurting Minorities Today.” ↩

-

Linda Gordon, The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2017), 11–24. ↩

-

Gordon, The Second Coming of the KKK. ↩

-

Bill McGraw, “Bringing Detroit’s Black Bottom back to (Virtual) Life,” Detroit Free Press, February 27, 2017, link. ↩

-

McGraw, “Bringing Detroit’s Black Bottom back to (Virtual) Life.” ↩

-

Geneviève Fabre and Michel Feith, Temples for Tomorrow: Looking Back at the Harlem Renaissance (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2001). ↩

-

Fabre and Feith, Temples for Tomorrow. ↩

-

Quinton Johnstone, “The Federal Renewal Program,” Faculty Scholarship Series, Yale Law School Legal Scholarship Repository, 1958, link. ↩

-

Robert Moses, “Robert Moses on Slum Clearance” (speech, April 17, 1958), New York Public Radio Archive Collections, link. ↩

-

US Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Section 312, Processing,” January 30, 1973, link. ↩

-

Richard Weingroff, “Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, Creating the Interstate System,” Federal Highway Administration, vol. 60, no.1 (Summer 1996), link. ↩

-

June Manning Thomas, “Progress amidst Decline,” in Redevelopment and Race: Planning a Finer City in Postwar Detroit (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2013), 127–203. ↩

-

Thomas, “Progress amidst Decline.” ↩

-

Jeremy Williams, Detroit: The Black Bottom Community (Chicago: Arcadia Publishing, 2009), 45–125. ↩

-

Richard Bak, Detroit across Three Centuries (Chelsea: Sleeping Bear Press, 2001), 130, 159. ↩

-

Ken Coleman, “Black Bottom and Paradise Valley: Center of Black Life in Detroit,” Michigan Chronicle, February 2, 2017, link. ↩

-

Corine Vermeulen, “Living with Mies: The Towers at Lafayette Park,” Places Journal, April 2012, link. ↩

-

Michele Norris, “Sitting on the Porch: Not a Place but a State of Being,” National Public Radio, July 28, 2006, link. ↩

-

Barbara Speed, “New York Destroyed a Village Full of African-American Landowners to Create Central Park,” City Metric, March 30, 2015, link. ↩

-

Speed, “New York Destroyed a Village Full of African-American Landowners to Create Central Park.” ↩

-

Speed, “New York Destroyed a Village Full of African-American Landowners to Create Central Park.” ↩

-

Nathaniel Rich, “When Parks Were Radical,” the Atlantic, September 2016, link. ↩

-

Rich, “When Parks Were Radical.” ↩

-

Rich, “When Parks Were Radical.” ↩

-

Douglas Martin, “A Village Dies, a Park Is Born,” the New York Times, January 31, 1997, link. ↩

-

Martin, “A Village Dies, a Park Is Born.” ↩

Ujijji Davis, PLA, is a landscape architect who focuses on design and planning efforts based in Detroit. Her work includes landscape and urban design, master planning, and strategic implementation. Her complementary background in urban planning is driven by a passion for authentic community engagement and research as foundational to successful design. Her research includes topics on anti-displacement, vernacular landscapes, and the relationship between arts and the economic success of cities.