Comrade Mirko Šipka is having strange dreams. 1 The last one, of his own suicide, really shook him up. He lives in Yugoslavia, sometime after 2014, drives a Zastava 1001 (the first “Yugo” was an export-ready model name for the Zastava 102), and takes the high-speed, ultra-modern electro-magnetic train between Skopje and Ljubljana for business travel.2 Šipka is married, childless, and his wife and mistress know about and like each other (a sure sign that he might be a figment of a middle-aged man’s imagination, even in post-socialism). His strange dreams take him to visit five-story, weather-stained, boxy concrete buildings, dilapidated beyond anything he has ever seen.

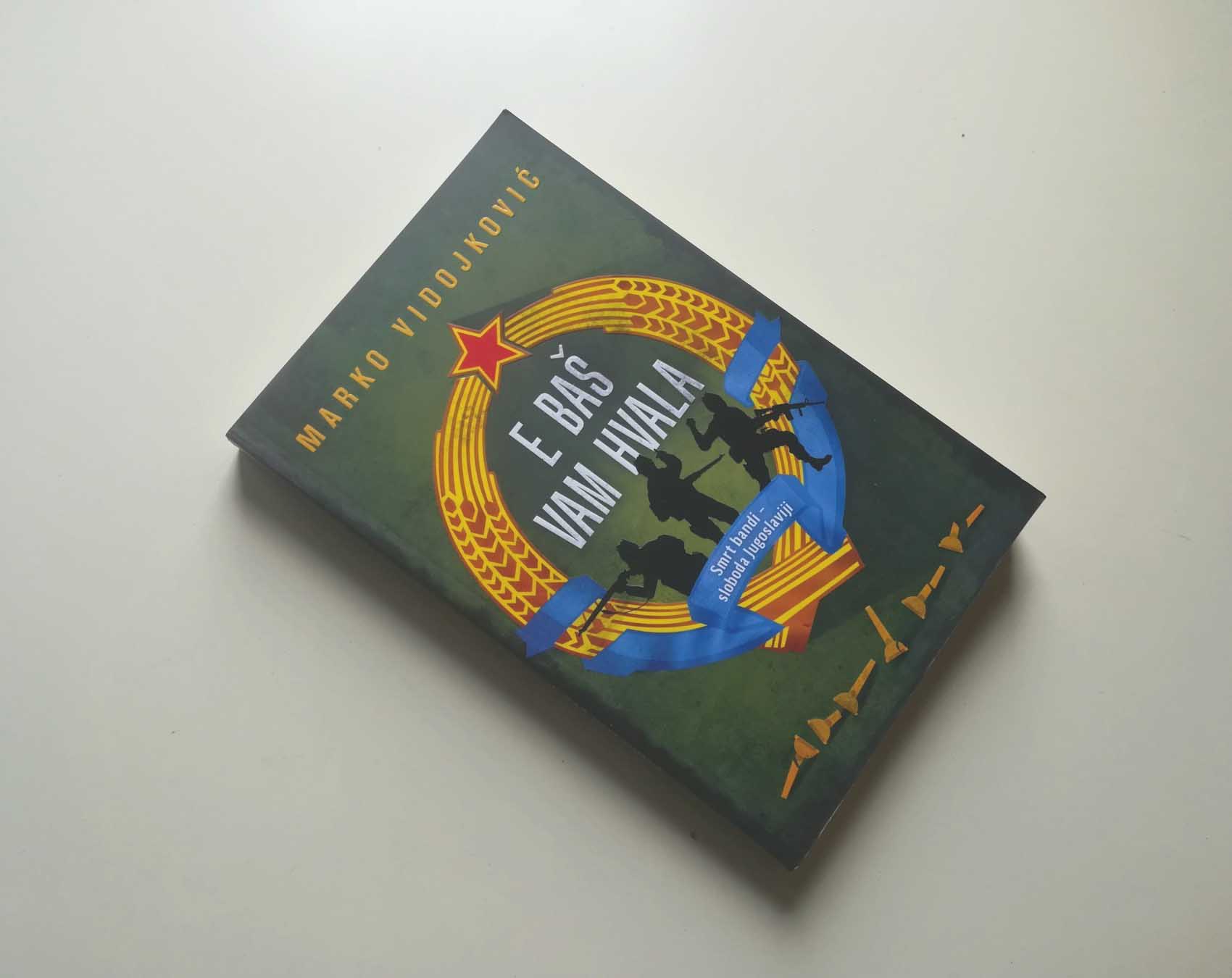

You likely have not had the chance to encounter Mirko Šipka. In order to come in contact with the description of the super-Yugoslavia in which he lives at the beginning of E Baš Vam Hvala (which translates to Thanks a Lot), a novel published in Belgrade in 2017, you would need to speak one of the national languages splintered from the official Serbocroatian, Serbo-Croatian, or Croato-Serbian language.3 But you might know another fictional character he is based on: Fox Mulder of The X-Files. Like Fox Mulder, Mirko is a special detective in charge of paranormal activities in Yugoslavia circa 2016. He also embodies the mannerisms and cool of the manly, mustached, and shrewd partisan guerrilla fighters from the mid-1970s Yugo TV series Povratak Otpisanih (The Return of the Written-Off), while his name links back to a once-famous comic book about the anti-fascist adventures of a boy named Mirko and his friend Slavko, sometime during the Second World War. Mirko Šipka is aware of the various characters that his fictional life seems to reference.4 He remarks on them with irony, and in passing; they are household references in his life, the way they indeed might be for any forty-plus-year-old living in an urban center somewhere in the ex-Yugo territory. As part of his job, he uses a fake identity to comment on posts he scrolls through on the “hate Yugoslavia” Facebook page. The country, he explains, is hated for its two decades of uninterrupted world domination in all sports, overly powerful legal weed, and super-caloric foods.

His dreams of the gray, neglected parts of Belgrade, and of what seems to him like his own internment (post-suicide) and orphaned child (in another dimension), are signs that two parallel realities might be starting to communicate. One “super”—albeit with unmistakable elements of autocracy, violence, and nationalism—and the other desperate, and dark, with Mirko’s dad worn out by the piling up of historical and private events and too wise to be fooled by the drone of his constantly running (reality) TV. It is, of course, Mirko Šipka’s (our Balkan Mulder’s) task to get to the bottom of these disconcerting ruptures, portals between the two realities, not the least because he himself seems to be falling back and forth through them.

The basic plot of Thanks a Lot, the satirical sci-fi novel written by Marko Vidojković, is enabled by a theoretical idea in quantum physics (and a fictional event). Its two realities emerge from a split in the fabric of the universe effected by the (fictional) crash of a Boeing 737 headed to Dubrovnik, which wipes out the entire cabinet and presidents of Yugoslavia’s Republics while they are headed to a conference in June of 1989. Until this point, one assumes, things had gone more or less as they did historically: the mostly rural, unevenly developed regions of Yugoslavia emerged out of the Second World War (and the remains of the kingdom of Yugoslavia) with major damage to their urban centers, vast human casualties, war-exacerbated ethnic conflicts, and a wartime revolution. With some help from the mapmakers at Yalta, in the midst of postwar confusion and local politics, these soon turned into socialist republics that together re-formed Yugoslavia in its new federalist form, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. This was followed by a definitive break with the Soviet Union in 1948. The break with Stalin, locally famous as “Tito’s ‘no,’” prompted the party leadership and Josip Broz Tito—the country’s long-term all-powerful president and commander in chief—to look for its own path to socialism, a path that would lead to its important experiment in the organization of labor, self-management, and later to combinations of state and market economies. It also directly prefigured Yugoslavia’s leadership in the Non-Aligned movement. Tito died in 1980. That year, after several weeks of breathless attention to the news broadcasts across the country, from a well-equipped hospital in Slovenia, his remains traveled very slowly on the presidential “blue train” from Ljubljana to their resting place in the “house of flowers” in Belgrade.5

The year 1989, which Vidojković picked as a fateful year of the crash, was an important one indeed. This annus mirabilis everywhere else in Eastern Europe marked the six-hundred-year anniversary of the “Kosovo battle” in Yugoslavia.6 Slobodan Milošević gave an inflammatory nationalist speech on its historic site, and politicians walked out on one another in the parliament meetings, spoiling the already slim chances of the fourth cabinet since Tito’s death (with Ante Marković at the helm) to keep things together.7

By eliminating the cabinet’s greedy political ambitions and jockeying for power in the aftermath of Tito’s death—which was historically followed by a dervish dance of comparatively merely life-size presidents rotating in from each of Yugoslavia’s six republics—Vidojković’s plane crash also invites readers to imagine the world cleared of the effects of some of the key voices that historically fueled nationalisms from the highest governmental stages. Two parallel realities are thus formed in the novel, one in which the crash occurred and another in which it did not, one in which the multiethnic socialist country prospered, and another in which it fell apart in a bloody civil war.

This novel has been on my mind since I visited Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia 1948–1980 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in July. During the first few minutes of the exhibition’s opening night, it seemed one of Vidojković’s portals had opened. At the entry, some of MoMA’s (mostly female) workers were handing out leaflets, seeking solidarity among the visitors for their negotiations with the institution for fairer wages and better conditions of work. They welcomed the fact that MoMA was lending its stage and cultural authority to the architectural artifacts of Yugoslavia’s “ideals and utopian goals.”8 It seemed to them that an institution so enlightened as to put up this exhibition, and frame it as a “testament…to architecture’s potential for social engagement,” could be held responsible for a follow-through closer to home as well.

Emanating in all directions from the DJ station in the courtyard were heroic verses of the 1948 “Svečana Pesma” (Festive Song): “Be proud of yourself, Yugoslavia…you were born from battle…”9 It washed over some without much notice, like Muzak on a hot New York summer evening, but for the voluntary and involuntary refugees from the once real Yugoslavia like myself, it instantly released a deeply programmed inner singing. Though accompanied by slight embarrassment, that mental hum was also wonderfully familiar, regardless of one’s attitude toward this piece of childhood indoctrination—working as it was supposed to.10 Palpably aligned with that familiar program was the wall text in the exhibition presenting the architectural historians’ version of the “super” Yugoslavia.

What kind of portal was this exactly? The ghost country Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, compared to Borges’s “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis”11 in 2012 by architecture historian Ákos Moravánszky,12 was here presented through evidence of some of its most optimistically produced architectural heritage, fitting neatly, salon-style—frames, glass, and all—on the now pastel walls of the third-floor galleries recently occupied by Frank Lloyd Wright’s archive, and all this during the “developer presidency” in the US.13 If you squint, the signals of the “historical show” might slowly crossfade between Wright’s archive (opened up in its most recent MoMA engagement by numerous historians to more complicated narratives of American modernism) and Yugoslavia’s socialist architectural heritage, but I am getting ahead of myself.14

MoMA’s visitors and many future readers of the (already) award-winning catalogue of Toward a Concrete Utopia will indeed most likely “owe their discovery of”15 Yugoslavia to the Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design, Martino Stierli; the visiting curator Vladimir Kulić, an incoming associate professor at Iowa State University; with curatorial assistant Anna Kats and the members of their curatorial advisory board and research team.16 The epic task of rescuing artifacts that constitute Yugoslavia’s socialist architectural heritage from the benign, entropic appetite of aging collective memory and neglect is here exacerbated by various forms of local and global political investment in forgetting their meaning. It is further complicated by the reverberations of the Cold War epistemic divide, which has ensured the exclusion of Second World narratives from the cannon that MoMA itself has had a hand in establishing.17 The flourishing of a contemporary form of orientalism enabled by social media’s discovery and proliferation of the region’s formally expressive anti-fascist monuments, stained concrete, and melancholy disrepair is only the most recent development that begs for more specificity and history. But in the larger exhibition calculus, it perhaps also served as preliminary proof of possible (general) interest in Yugoslavia’s architectural heritage.18 Especially when viewed against this backdrop, the preservation, assembly, and display of over four hundred documents of Yugoslavia’s architecture in MoMA’s third-floor galleries—and amplified by this institution’s cultural authority—is a generous and important offering to the discipline and to once-Yugoslavia’s architects.

This might be the moment to confess that I am simultaneously many different audiences for this show. I am from Belgrade. I grew up and loved my childhood in socialist Yugoslavia between ’72 and ’91, despite all its various shortages of food, coffee, and detergent in the 1980s (the fact of childhood blissfully absolved me of worrying about putting food on the table, though my parents’ anxiety was always palpable).19 Though it reliably inspired survival instincts, scarcity had an important socializing dimension as well. Despite the general slogan-exhaustion at school, “common good” resonated for a generation that lived in the latter part of the “golden years” captured by Toward a Concrete Utopia’s historical bracketing.

As my final year of high school drew to an end, having participated in a series of anti-Milošević protests, sat for entry exams, and gotten into the faculty of architecture, in 1991, I emptied my parents’ small stash of foreign currency and flew to New York (upstate, that is) to try out my luck at US schools—just a vague ambition at the beginning of that trip. After leaving the country, I witnessed it fall apart via US media coverage of the events. The roundtrip ticket fatefully voided. Like many who started their immigrant journey at that time, I am a statistic of Yugoslavia’s destruction. I am also a child of two architects who helped build large swaths of Belgrade housing and collaborated with many of the characters included in the show, more or less amicably, but always through the structures of “self-managed” architectural enterprises as well as government and academic centers dedicated to architecture and construction on both the city and the regional scales. I went to an architecture high school, and via a mechanism available for youth work—omladinska zadruga (youth cooperative)—I worked in the summers in a self-managed architectural enterprise in Belgrade. Mostly women, architects and technicians sat in my room filled with drafting tables, cigarette smoke, white coats, and the occasional whiff of ammonia from the nearby blueprint room.

I was automatically made part of Yugoslavia’s socialist youth, like everyone my age, but all of the family’s property on my mother’s side had been expropriated or nationalized after the Second World War, and the family narratives of lack and violation were hard to ignore, requiring a form of continuous balancing between the ideologies presented for consumption at school and at home.20 We lived in an apartment we rented from the state, in a building that was built and once owned by my great-grandfather, where well after the 6 a.m. to 3 p.m. workday in the design bureau of Hidrotehnika (a subgroup within a construction and design company Beogradgradnja), my parents sat at their drafting table designing modest modern apartments for others.21 They would have never met were it not for socialist Yugoslavia and the architecture bureau that brought them together across class and ethnic divides, party cardholder and “enemy of the state.” And yes, though the credit they received for it was skewed toward my father, they participated equally in constructing that socialist Yugoslavia, the only way an architect can: with fundamental optimism about the task at hand.22

It is the constellation of these personal contradictions that launched me into scholarship about Second World architects, and nearly all the questions that have seemed important to me in this long-term endeavor involve the circumstances and nature of the Second World architects’ labor. What motivated them to practice architecture? What political and aesthetic assumptions did they make in the course of their practice? How often did they receive ideological and aesthetic guidance from the party and state ideologues? In what disciplinary conversations did they participate and how? How did they see their role in the inevitable materialization of their local socialist utopias, or in the occasional architectural materialization of the key narratives of self-determination in the Third World countries they traveled to “on business”?

Before asking or answering any such questions regarding Yugoslavia’s architectural heritage in the public arena, MoMA’s curatorial team had the unenviable task of establishing some amount of common ground—the scale of the task proportionate to the Cold War epistemic divide itself. It had to teach its audiences everything about Yugoslavia’s (SFRY’s) architecture. Pause for a moment on the enormity of the task. For every object in the show, there is a story of tracking down and sometimes literally rescuing the artifacts.23 And for every artifact included in the show, there are at least three others that did not make the cut, and then of course, there are those whose archival traces have been irretrievably lost in (post-socialist) transition.24 The wall text introducing the exhibition promises more than a degree of familiarity, inviting the audience to contemplate real, systemic, and historical alterity. It asks its visitors, the general and the architectural public alike, to perform a demanding act of political and historical imagination and to think of neither socialism (with all of its Cold War–era connotations) nor capitalism (with its ever more apparent shortcomings) but of a “third way.” It echoes thus Kulić and Mrduljaš’s earlier framing of the country’s architectural heritage in terms of in-betweenness,25 though offered now with more urgency.26 Maybe the historical moment is right everywhere—in the context within which it is presented as well as in the context it represents—for the reception of Yugoslavia’s, or at least Toward a Concrete Utopia’s project. In the First World, the need to plan for the survival of all (and the thriving of all if we can get to it) could not be more apparent, while the lessons of Yugoslavia’s ruin are an urgent warning applicable now in all corners of the world. Within the territories of ex-Yugoslavia such instrumentality of this exhibition would be symptomatic of what philosopher Boris Buden described as the inevitable transformation of the historical experience of socialism into forms of cultural memory.27 Vidojković’s sci-fi fits the bill as well. Both this novel and the exhibition are types of cultural artifacts that evince the moment when all that is left after post-communist transition is “hope without society.” But then, cultural memory, Buden suggests, can be understood as an instrument of retro-utopia, which just might help us reconstitute historical knowledge by sharing it in public.

Toward a Concrete Utopia begins with a commissioned video installation by Mila Turajlić, featuring newsreel clips of work on the construction of Yugoslavia’s railways and housing. The first video installation rapidly traverses a long historical period, from volunteer brigades, through parades that celebrated architectural and infrastructural production, to the construction of later blocks (61, 62) in New Belgrade, and ending with a rock band traveling the streets. “Brotherhood,” “Unity,” “Yugoslavia,” are yelled at different times with different inflections (as local rock bands in the 1980s and 1990s would have done) and snippets of the “Festive Song” repeating on a loop. The exhibition also launches with a large map of the general plan of Belgrade adopted in 1950, after a number of earlier attempts to plan the new federal capital of Yugoslavia failed.28 The map that hung in the main conference room of the Institute for Urbanism in Belgrade as the promise made to the city by its planners (and lately as the testament to a time when strategic planning, long-term goals, and common good had more purchase) opens up the exhibition’s theme of Modernization, which loosely corresponds with the beginnings of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the postwar reconstruction.

Elements of central planning, the five-year increment, and demographic thinking “speak” through the artifacts at the very beginning of the Concrete Utopia enfilade: population maps, conceptions of tourism across the entire territory of the country, the plans for the Adriatic Coast as a totality and a collective good, and plans for the long-term development of New Belgrade. They represent breathtaking boldness, executed by numerous and nameless members of the federal-, republic- and city-based urban institutes. This is followed by some of the key experiments in structural engineering including Fair buildings in Belgrade, Poljud Stadium in Split, and Zlatibor Hotel in Uzice. Visitors are greeted by a large, frontally hung photograph of the rain-stained concrete body of that hotel, one of Valentin Jeck’s photographs explicitly commissioned for the show.29 The exhibition also includes original models and drawings, as well as models produced by Cooper Union and Florida Atlantic University students, furniture pieces, and several works from MoMA’s permanent collection, including a newly reacquired and refreshed Kiosk K67. That vibrant object, which joyfully defies the material palette of the show, had excited Emilio Ambasz enough to acquire it for MoMA after noticing it in a magazine in 1970, only for it to later disappear from the collection.30 An orange Kiosk K67 in front of my elementary school sold the most delicious hotdogs in a bun affordable to kids on class break, and the one near my home sold newspapers. In the 1990s all across Belgrade, these kiosks delivered the small-scale gray economies of embargo survival, one specialized smuggler at a time. They have only recently been removed, their removal marking Serbia’s inching toward the EU.

In addition to Modernization, the organization of the show’s artifacts includes three more themes that flow from one to the other—Global Networks, Everyday Life, and Identities. The four main themes are further subdivided into Urbanization, Technological Modernization, The Architecture of the “Social Standard,” The Reconstruction of Skopje, Exporting Architecture, Tourist Infrastructures, Design, Housing, Regional Idioms, and Monuments. This complicates the conceptual apparatus of the exhibition, but it may have helped the curators negotiate between desires for narrative comprehensiveness—i.e. the history of Yugoslavian architecture—and the impasses of archive and gallery space. These ten headings (barely smaller than the four main topics) also allow for a certain amount of overlap, absolving the visitors from having to constantly reframe their view. Technological Modernization, ending more or less with the Aeronautical museum in Belgrade, gives way to Architectures supporting the Social Standard: libraries, kindergartens, workers’ universities, and museums. The contemporary intricacies and fractal repetition of ninety-nine cubes and domes of Kosovo library in Priština are likely now, or soon, to be on top of every Pinterest board dedicated to libraries. The artifacts representing the finally reopened (after ten years of glacial reconstruction) and beautifully restored Museum of Modern Art in Belgrade face off with sculptural concrete scoops of kindergarten Rod in Ljubljana.

Records of Skopje’s reconstruction efforts, in the wake of its devastating earthquake in 1963—vast, heroic, and international—occupy a generous territory in the gallery. Disposition of that gallery space enables both distant and closeup views, everything brimming with optimism. At the end of the loop through Skopje, one encounters the wall and the vitrines explaining Energoprojekt’s involvement in Lagos. Together Skopje (importer of foreign expertise) and Energoprojekt’s involvement in Lagos (export of architecture) stand in for Global Networks. These are examples of the way in which the conceptual expansion of the architectural market and discursive and technical networks for socialist Yugoslavian firms correlated directly with the country’s leadership in the Non-Aligned movement. The Energoprojekt section includes one of two actual photographs of architects at work, presenting Milica Šterić, the director of the architecture and urbanism division of the company. The other image of architects at work shows Kenzō Tange and his team in Skopje. Though both of these photographs help fix the image of the globalization of architectural practice in this context, presenting various lines of emancipation as well as multiple architects at work together, they are not enough to offset the signal sent by the individual names attached to each artifact in the exhibition.31

Installation view of Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, July 15, 2018–January 13, 2019. Photograph by Martin Seck. © The Museum of Modern Art, 2018.

As a timeout of sorts, the architectural infrastructure of socialist and (more glam, or at least more individualistic) First World vacations on the Adriatic Coast flick through a slide show presentation, as if reminiscing about a family trip. The Housing and Design sections of the exhibition—where Split 3 fights for attention with sitcoms and the Kiosk K67—present a tiny fraction of housing produced in the period from 1948 to 1980, as well as some key design objects that tracked directly with the rise in demand for consumer goods and the emergence of product design as a discipline in this context. Those goods, just as the desire for them had historically done, distract a bit from imagining housing as a constitutional guarantee. Standardized, but thoughtfully governed by preset minimums and maximums (not profit), and importantly promised to all, housing was a right whether one worked in a school, a factory, an architecture office, or for the Yugoslav Army. Self-managed companies that were doing well, as well as state agencies, were the key investors in housing, resulting eventually in social diversity in the housing districts, though importantly, the process did not work out for all.

The space dedicated to illuminating ways in which identity intersected with architectural issues progresses from national and vernacular identities to a collective anti-fascist one, with every artifact that can be placed on this spectrum testifying directly to architecture’s participation in the imagination and construction of collective identities. There is not a lot of evidence in the exhibition of people engaging the expressive anti-fascist monuments, which command the landscapes around them like lonely beacons, but most members of that socialist youth I belonged to (which likely included every politician active now within the territory of Yugoslavia) were taken on pilgrimages to visit them. Imagine busloads of kids with their home-packed lunches contemplating various whys and leaving with some explanation that they collectively received about the Second World War, its casualties, the fight against fascism, brotherhood and unity. If lucky, those approximated Bogdan Bogdanović’s answers to his own question: “Why do we build these monuments? In order to encourage life after the orgy of destruction; In order to summon life in ourselves; In order to make life and death humanly possible; In order to exile evil from death.”32

The exhibition also includes four rooms dedicated to four male architects, chosen for their status as important public intellectuals in Yugoslavian architectural discourse: Vjenceslav Richter, Edvard Ravnikar, Juraj Neidhart, and Bogdan Bogdanović. They are thinkers of self-management, local (sometimes vernacular) identities, and monuments. The material in their monographic rooms situates them in the global and Yugoslavian discursive and academic networks. The choice of these specific architects, like most sections of the exhibition, spreads the “love” and regional representation almost evenly, thus re-enacting in curatorial terms the representational balancing constitutive of the political project of Yugoslavia.

The task of entering this ghost country’s material into global architectural history circulation might be directly opposed to the task of impressing MoMA’s audiences with what it could have meant to live and produce architecture in the “third way.” That crossfade between MoMA’s recent Wright show (which multiplied narratives) and Toward a Concrete Utopia (which consolidates kaleidoscopic historical and architectural narratives into a meta one about constructing Yugoslavia) is relevant here, for its plausibility highlights the institutional inertias at work. There is a certain amount of comfort and perhaps even expectation on the side of MoMA’s audiences and its custodians that a truly historical show must include some (original) types of artifacts and cannot include others, and that any history worth writing is one produced by masters, or at least individual authors, and that without architectural objects and artifacts, nothing can be said. It is extremely hard to present structural, systemic alterity—predicated on different forms of ownership and authorship—while complying with these requirements. This puts incredible pressure on the wall text to deliver on the promise of probing the complex relationship between architecture, the construction of the social and political project of Yugoslavia, and concrete as a material. And as always, especially hard to transmit are nuance, multiplicity, and uncertainty—all key parts of Yugoslavia’s political and architectural history.

You might be wondering: what happens to the special agent Mirko Šipka? He ends up leaving the super Yugoslavian reality and joining his son and father in the other (more familiar, contemporary) universe in which each of Yugoslavia’s republics is enjoying, or enduring, its national transition to global capitalism and the EU. It is useful to “go there” with Mirko, and Valentin Jeck’s photographs present a viable portal. His large, melancholy photographs set the pace for the exhibition. Appearing in every part of the show, they often overpower the otherwise “objective” archival signals, though perhaps they give some of the historical material its concrete body and speak effectively to MoMA’s general audience, as Martino Stierli proposes.33 Although they come without an explicit explanation, they are most interesting to contemplate indeed as “portals” to contemporary forms of neglect and destruction, both of the architecture they present and of the project of Yugoslavia that those architectures in part materialized. To the historical “super” Yugoslavia on display around them, Jeck’s photographs serve as the gray, dilapidated, post-transition “now”—Mirko’s and our own. But the last, devastating article of the show’s catalog by Andrew Herscher urges readers not to succumb to the inertia of common imagining that the project of socialist Yugoslavia failed somehow naturally, because it had to fail. On the contrary, Herscher asks us to contemplate the difference between “failure of a political project and the destruction of a political project,” which in his mind requires “attention to both the narration of that project’s past and assays of its potential futures.”34

For most visitors, Toward a Concrete Utopia is a lesson in the history of Yugoslavia’s architecture. Some, like the elderly father and middle-aged son I observed on one of my visits to the show, will be curious to locate the hotel they have recently stayed at, or verify to whom that extraordinary surrealist concrete flower was dedicated. And that is a great accomplishment—even if self-management remains mysterious, and some aspects of history end up a bit distorted by MoMA’s institutional habits of seeing.35 As historical records now themselves, the exhibition and its catalog will surely enable more historical work to come. Hopefully ad agencies will no longer be tempted to film their eyeware commercials on the grounds of Jasenovac or in Tjentište.36

For the former inhabitants of Yugoslavia, twenty-five years after its collapse, the show, and the elements of everyday life it presents, frame a confrontation with an important historical feeling: nostalgia.37 But many elements of life in socialist Yugoslavia and of its violent breakup make it impossible for this audience’s nostalgia to be restorative. In the late Svetlana Boym’s brilliant definition, nostalgia is not simply a personal feeling but a historical and collective one. She insists on a typological distinction between two nostalgias. Restorative nostalgia is deadly serious, resting on symbols and aiming for absolute truths. Reflective nostalgia, on the other hand, has the capacity to operate sideways, through humor and irony, allowing for multiple and contradictory narratives to coexist. It also has the capacity to look forward. Reflective nostalgia is worth cultivating in the population of ex-Yugoslavians and their children—who would hardly recognize the outlines of their parents’ former country, or fully understand the complexity of its successes or its breakup—because looking forward together is the most necessary for the region’s economic and political future.

Vidojković insists that his novel is not about Yugonostalgia “because those who helped destroy the country are still amongst us.”38 And though I admit to experiencing pangs of my own nostalgia in confronting this material and to detecting it in various guises throughout the show, I want to suggest that the most important way to see this exhibition is not, or not only as, a “historical show” but also as a contemporary reenactment: as a reconstitution of that emancipatory and unifying project of Yugoslavia by a group of young researchers across the old Yugoslavian territory.39 This would indeed align it with Buden’s retro-utopian objects and acts, which “do not simply document the truth of our past as much as they document the truth of our relationship with that past, which is simultaneously also a truth about a very specific belief in a better future.”40 So, although it is very significant that examples of Yugoslavian architecture arrived to MoMA, the work of reconstituting the Yugoslavian project through architectural history is bigger than this MoMA show. It has started with an older generation of architectural historians in the ex-Yugo countries and across the Second and First World contexts, some of them at the helm of the curatorial team here, but not all included.41 Importantly, the curatorial advisory team (whose names in that role are listed on page 179 of the catalog) includes researchers whose age ensures that the only way they access historical knowledge about the Yugoslavian project and architecture is through forms of cultural memory, not via their own lived experience.42 Along with the theorist Branislav Dimitrijević, I believe that cultural production has a way of structuring possibility and that this new generation inheriting the cultural memories of Yugoslavia, however sanitized of contradictions or uncertainty they might seem to me, has the capacity to retool the project for the future.43 This year, on Yugoslavia’s hundred-year anniversary (measured from its inception as a kingdom in 1918, or its seventy-five-year anniversary since the inception of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia during the Second World War in 1943) and as a nod to all of us who maintain citizenship in it as an idea, I sign off with Vidojković’s salutation: Smrt Bandi—Sloboda Jugoslaviji.44

-

You will have noticed that the Š in Šipka appears in a different font, which is still subtler than the lowercase, serif č in my name above. In my US passport Miljački is spelled with a simple c, no diacritics. The ability to deploy these Slavic language diacritics easily in the most recent iOS have made me wonder how this new convenience will affect my legal documents from now on. My email address does not include diacritics, my early publishing did not include č. If you have a diacritic in your name, you of course know that not having one transforms the sound of your name in your name’s original language. I have generally taken this to be part of a Cold War divide in font systems that I simply had to contend with. So, when the Avery Review was only able to produce a lower case č in my name otherwise written in capital letters, it seemed appropriate to accept the somewhat comical turn of font troubles as part of this article’s content and tone. ↩

-

Marko Vidojković, E Baš Vam Hvala, Smrt Bandi Sloboda Jugoslaviji (Belgrade, Laguna 2017). ↩

-

The language, or the constellation of south Slavic languages from Montenegro to Croatia, was named as such by one of the Grimm brothers, Jacob, in 1824, and was most recently standardized by an agreement among local linguists in 1954. The splintering and purposeful diversion between them has been going on throughout the second half of the 20th century, and it has been embraced with renewed vigor since the 1990s. ↩

-

Šipka means “a rod.” ↩

-

The naming of these elements of Tito’s transportation (“blue train” was a kind of a “Train Force One”) and resting place was part of a specific choreography that regulated the expressions of Tito’s personality cult—the mix of the official representations of “man of the people,” his own glamorous lifestyle and what Branislav Dimitrijević has called “‘grassroots’ modes of amateurish representations and expressions of respect,” and adoration. See Branislav Dimitrijević, “Titomaginarium” (a brief introduction to the ambivalence of the “cult” of Josip Broz Tito in socialist Yugoslavia) in the catalog for Monuments Should Not Be Trusted, curated by Lina Džuverović (Nottingham, UK: Nottingham Contemporary, 2016). ↩

-

The battle on Gazimestan in 1389, between Serbian and Ottoman forces, marked the beginning of the five-century occupation of Serbia by the Ottoman Empire. This battle is an important piece of the foundational national mythology. Famous in its devastating loss (both literally in terms of casualties for the time, and historically as a decisive beginning of a very long period of oppression), it has fueled cultural and artistic production both during the Ottoman occupation and in the twentieth century. ↩

-

A Croatian philosopher living and working in Berlin, Boris Buden has been an important commentator on the postsocialist transition everywhere in the Second World. In his Zona Prelaska, O kraju Postkomunizma (Belgrade: Fabrika Knjiga, 2012, first published in German in 2009), he proposes a devastating reading of this year, 1989 as well, which directly connects the West’s view of the 1989 rise of the Eastern European people against their oppressive systems with the nationalist narratives that followed across the territory of the former Eastern Bloc, and arrived in Yugoslavia even before 1989 and the view it prompted of the “compensatory” nature of the Eastern European revolutions. The notion that Eastern European revolutions of 1989 were revolutions in reverse, that these people were “returning” to liberal capitalism, solidified the function of Verdery’s “Cold War epistemic divide” and infantilized the subjects of postsocialism everywhere. It also “naturally” re-initiated singular nation narratives. ↩

-

The pink leaflet I walked away with starts with this quote from the curatorial statement. The leaflet itself does not have a title, but it does bear the mark of New York City’s Technical Office Professional Union, UAW Local 2110, with hashtags on the bottom leading to the same entity. ↩

-

“Svečana Pesma,” with lyrics by poet Mira Alečković and tune from an earlier work “Novoj Jugoslaviji,” composed by Nikola Hercigonja, was in 1959 proposed as the possible new anthem of the country, but the proposal was not accepted. ↩

-

I imagine some Americans are similarly ambivalent these days when their inner recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance is triggered. ↩

-

Jorge Luis Borges, “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” Labyrinths: Selected Stories & Other Writings (New York: New Directions Books, 1964): 3–18. ↩

-

Ákos Moravánszky, “Preface—Reassembling Yugoslav Architecture,” in Vladimir Kulić and Maroje Mrduljaš, Modernism In-between: The Mediatory Architecture of Socialist Yugoslavia (Berlin: Jovis, 2012). ↩

-

Aptly described as such by the Avery Review’s editors in issue 21. ↩

-

Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive ran from June 12 to October 1, 2017, at MoMA. The show was organized by Barry Bergdoll, curator in the Department of Architecture and Design, with Jennifer Gray, project research assistant in the Department of Architecture and Design, at MoMA. ↩

-

You might remember that Borges starts his story, “I owe the discovery of Uqbar to the conjunction of a mirror and an encyclopedia.” Borges, “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” 3. ↩

-

Vladimir Kulić and Martino Stierli, eds., Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia 1948–1980 (MoMA, 2018), was placed among the top ten architecture books of 2018 by the Frankfurt Book Fair and Deutsches Architeckturmusem. ↩

-

Anthropologist Katherine Verdery theorized the discursive orders that accompanied the Cold War political order as a particular kind of Cold War epistemology in What Was Socialism, and What Comes Next? (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996). ↩

-

See Vladimir Kulić’s brilliant article on the topic, “Orientalizing Socialism: Architecture, Media, and the Representations of Eastern Europe,” Architectural Histories, vol. 6, no. 1 (June 2018), http://doi.org/10.5334/ah.273. ↩

-

According to art and cultural theorist Branislav Dimitrijević’s important study of the way in which the capitalist consumerist imaginary might be implicated in the economic and political destruction of the Yugoslavian project, the entirety of my mostly happy socialist youth was situated already in the period of postsocialist transition, which, according to him, began already in the 1960s, but which was also understood by many as the easing of the dogmatic, centrally planned organization of production and private lives (including consumption). He suggests that in the 1970s citizens of Yugoslavia spent eight times the money they made, with the country’s deficit growing twenty-fold in the following decade, precisely as a result of managing the gap between rising consumerism and indices of production. Branislav Dimitrijević, Potrošeni Sociajalizam: Kultura, konzumerizam i društvena imaginacija u Jugoslaviji, 1950–1974 (Belgrade: Fabrika Knjiga, 2016). ↩

-

I credit that training in balancing with helping most members of my family not swing to the nationalist, religious, even royalist at times, right, despite plausible family history reasons for it. ↩

-

A decade after my parents retired and were given funny stocks for it as worker-owners in the company’s erstwhile self-management, Hidrotehnika went bankrupt, and was privatized at an auction in 2009. Around this time, it was also the subject of a documentary Abuse of Power, episode 5 for Insajder, an investigative journalism series by the TV station B92. ↩

-

The gender dynamic in architecture companies was aptly described in Theodossis Issaias and Anna Kats, “Gender and the Production of Space in Postwar Yugoslavia,” in Toward a Concrete Utopia, 97–100. Though equality was guaranteed ideologically, it was out of reach practically. On more than one occasion, my mom said, “We could have been like the Marušić couple (Milenija and Darko)…or, the Bakić couple (Ljiljana and Dragoljub),” sometimes melancholically, sometimes in frustration. Those two architect couples appearing to her as the type of spotlight that might have been within reach for Ivanka (Stanković) and Stevan Miljački from their position as glavni i odgovorni (principle and responsible) architects at Hidrotehnika. ↩

-

I mention some of the most interesting of those that I managed to collect from the curatorial team in my review of Toward a Concrete Utopia for docomomo Journal 59 – An Eastern Europe Vision. ↩

-

The research for the show has been accompanied by an enormous digitization effort by some members of the curatorial advisory board, and the first pieces of this important work are now being made public. Jelica Jovanović and Ljubica Slavković have begun an online archive of Architectural modernism in preparation for an important “collateral” event, “Stvaranje konkretne utopije: arhitektura Jugoslavije, 1948-1980” (“Making of Concrete Utopia: Architecture of Yugoslavia, 1948-1980”) at the Center for Cultural Decontamination in Belgrade in November 2018. See their website, link. ↩

-

Vladimir Kulić and Maroje Mrduljaš, Modernism In-between: The Mediatory Architecture of Socialist Yugoslavia. ↩

-

Urgency here is suggested both in terms of contemplating that “third way” as a political option and seeing Yugoslavia as exceptional in the context of the Second World. ↩

-

In Zona Prelaska, Buden critiques the cultural sphere for perhaps emptying the social, but he also, invoking Charity Scribner’s Requiem for Communism, analyzes 1990s art works with explicit retro-utopian impulses as symptoms of a larger predicament that they may have anticipated. ↩

-

Ljiljana Blagojević, Novi Beograd: Osporeni Modernizam (Belgrade: Zavod za Udžbenike, Arhitektonski Fakultet Univerziteta, Zavod za zaštitu spomenika, 2007). ↩

-

The catalog and the wall text call out architects most responsible for these projects, as authors, with year of their birth but no affiliation to companies or research centers explained. Zlatibor Hotel is attributed to Svetlana Kana Radević, who indeed might be the most unique of examples included in the show, for unlike most architects in Yugoslavia at the time, she had her own private company. The design of the Fair in Belgrade included the architect Milorad Pantović, and engineers Branko Žezelj and Milan Krstić. The Poljud stadium: Boris Magaš. In the text you are reading, I want to resist invoking all of the individual architects’ names—not because they should not get credit but because authorship and ownership are intricately tied in every social system, and it would be erroneous to imagine private ateliers, small offices, or full-on competition in the free market for architecture in this context. Architects rarely acted on their own behalf alone. Academic work and memorial production (which provided a bit more room for what we might understand as authorship in the first world) followed vastly different models than the production of housing, civic buildings, and infrastructure. ↩

-

Juliet Kinchin, “Kiosk 67,” in Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980, 149. ↩

-

As mentioned in note 28, most architects in this context worked on behalf of self-managed enterprises, which they at least theoretically co-owned, or state, city and university institutes, but these are only invoked occasionally in the show if they functioned as lending institutions, not in their role as organizers of labor and authorship. ↩

-

I was lucky to see these statements posted by one of the members of the curatorial advisory board, Jelica Jovanović, as she was literally going through Bogdan Bogdanović’s personal archive in December 2018. ↩

-

“Toward a Concrete Utopia” conversation at Columbia GSAPP, October 5, 2018, link. ↩

-

Andrew Herscher, “Architecture, Destruction and the Destruction of Yugoslavia,” Toward a Concrete Utopia, 114. ↩

-

Self-management does receive a few important paragraphs in the catalog, notably in Maroje Mrduljaš’s “Architecture for a Self-Managing Socialism,” but it remains treated as an ideology in need of an architecture, as programmatic content, rather than as the basis for the organization of architectural labor. ↩

-

Just such videos staged on the site of the Jasenovac memorial in Croatia, produced by Valley Eyewear from Australia, surfaced online just a few months before Toward a Concrete Utopia opened, to an uproar on social media and by news establishments. ↩

-

I rely on the nuance in this term provided by Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (Basic Books, 2001). ↩

-

Vidojković makes this statement toward the end of a panel meant to promote the book in Belgrade in November 2017. See link. ↩

-

Though the socialist era was many things in Yugoslavia, it was also importantly optimistic about the prospects of a diverse, multiethnic, equitable, self-managed, and self-conscious collective. ↩

-

Buden, Zona Prelaska, 205. ↩

-

Both Vladimir Kulić and Maroje Mrduljaš have led and been part of a multiyear project “Unfinished Modernization: Between Utopia and Pragmatism,” which included fifty researchers and produced a traveling exhibition as well as an edited book by the same name, Vladimir Kulić and Maroje Mrduljaš, eds., Unfinished Modernisations: Between Utopia and Pragmatism (Zagreb: Udruzenje hrtvatskih arhitekata, 2012). ↩

-

They are: Tamara Bjazić Klarin, Matevz Čelik, Vladimir Deskov, Ana Ivanovska Deskov, Sanja Horvatinčić, Jovan Ivanovski, Jelica Jovanović, Matrina Malešić, Maroje Mrduljaš, Bekim Ramku, Arber Sadiki, Dubravka Sekulić, Irena Šentevska, Luka Skansi, Łukasz Stanek, Marta Vukotić Lazar, and Mejrema Zatrić. There were also two Mellon fellows involved in the project at MoMA: Mathew Worsnick and Theodosis Issaias, as well as an intern, Joana Heitor. ↩

-

The front part of this statement on the agency of culture, is of course the belief of many theorists of cultural production, and also of architects and pedagogues of architecture. But I align myself here with a specific set of statements that Dimitrijević made in an interview with Srećko Pulig in March 2017 for Peščanik, where he also acknowledged a generational divide with respect to the Yugoslavian idea. See link. ↩

-

This is a humorous cheer from Thanks a Lot, transmitting co-conspiratorial warmth and some amount of childhood partisan film melodrama and meaning: “Death to the Gang—Freedom to Yugoslavia.” It is based on another important salutation famously used to protest the German occupation in WWII: “Smrt Fašizmu, Sloboda Narodu!” (Death to Fascism, Freedom to the People). Warning: its intended mix of humor, self-deprecation, and hope here might only register for those “who know.” ↩

Ana Miljački is a critic, curator, and associate professor of architecture at MIT, where she teaches history, theory, and design and directs the MArch Program. Miljački was part of the three-member curatorial team, with Eva Franch i Gilabert and Ashley Schafer, of the US Pavilion at the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale. Miljački’s Un/Fair Use exhibition, co-curated with Sarah Hirschman, was presented at the Center for Architecture in New York in 2015 and at UC Berkeley’s Wurster Gallery in 2016. In 2018 Miljački launched the Critical Broadcasting Lab at MIT. She is the author of The Optimum Imperative: Czech Architecture for the Socialist Lifestyle 1938–1968 (Routledge, 2017), and the editor of Terms of Appropriation: Modern and Architecture and Global Exchange with Amanda Reeser Lawrence (Routledge, 2018).