I. The Apprentice

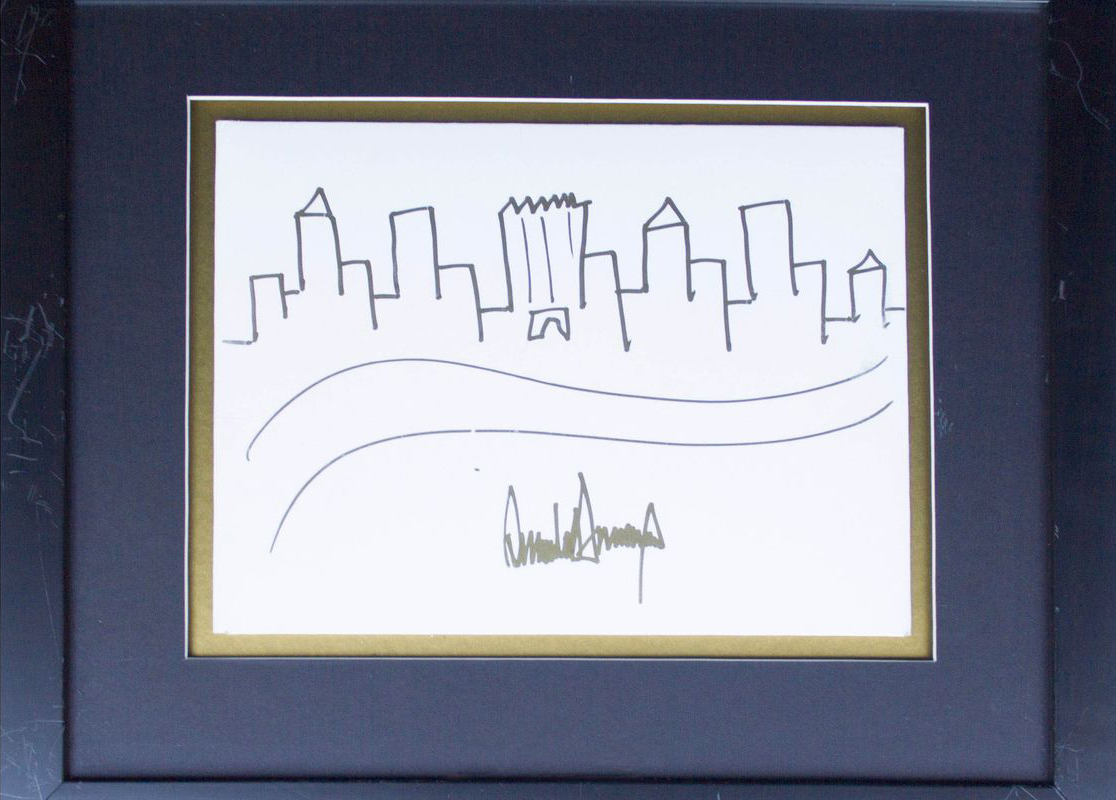

In September 2005, Pitney Bowes Inc., a Connecticut-based e-commerce and postage company, sponsored an online auction to promote World Literacy Month. Up for bid were “original envelopes” designed and autographed by celebrities from the realms of sports, entertainment, and politics, among them Donald Trump, who was enjoying more widespread name recognition from The Apprentice, then in its second season. Though most of the participants chose to draw figurative representations of themselves or animals, or to write inspirational mantras about the importance of reading, Trump decided to take the skyline of Manhattan as his subject, sketching an elevation of the city from the west. Rather than depicting the profile of New York’s most well-known skyscrapers or a single contour that would track the distinctive peaks and valleys of Manhattan’s business and residential districts, Trump’s doodle could be seen, through its repetition of the same “up and down” figure, as a linear motif—a kind of meander that never returns to itself.1 Nevertheless, the sketch is not entirely abstract. Three of the figures are punctuated with triangular caps at regular intervals, and, at the midpoint of the sequence, one “up” shape has been modified with a zigzag line and filled in with vertical stripes—an unmistakable allusion to the step-back roofline of Trump Tower, as it might be seen from below on Fifth Avenue. At the base, an upside down U suggests some kind of entrance, or perhaps an aborted attempt to draw a serif T. Below the skyline, Trump has included two parallel waves, representing the Hudson River—if we are to take the orientation of the Trump Tower façade literally—and his own signature, jotted down in gold.

The drawing resembles New York less than it corresponds, via its distortions, to Trump’s imaginary view of the city and the position of his residence and eponymous development among its high-rise competitors.2 Within this invented and inverted cityscape, Trump Tower emerges not merely as a building like other buildings, designed for residential and commercial use, but as the keystone of all perspectives, watchtower and fortress at once.3 Centered within this sequence, Trump Tower joins with its schematic neighbors, forming a continuous, crenellated, parapet across the back of the envelope.

How might this castellated style become legible in our present, fraught moment? Sketched at a point of transition between Trump’s career as a New York personality, famous within local tabloids and real estate circles, and a national figure, through the success of The Apprentice, the envelope might be seen, in retrospect, as heralding Trump’s future aspirations for sovereign power. However, the sketch also points back to the neo-medievalism of New York in the 1980s—a period in which Umberto Eco recognized the newly constructed Trump Tower and its contemporary Citicorp Building as “Manhattan castles” and “curious instances of a new feudalism with their courts open to peasants and merchants and the well-protected high-level apartments reserved for the lords.”4 While Eco only mentions these examples in passing as he roams among a series of cultural analogies between the fall of the Roman Empire and the dissolution of American hegemony in the late twentieth century, it is worth returning to this point of origin in order to consider the production and reception of Trump Tower in greater detail—and the way in which this building, and Trump himself, were already interpellated into a medieval fantasy long before he descended on an escalator, deus ex machina, to announce his bid for the presidency. What are the consequences of Trump’s imaginary relation to his real conditions of existence, now that his real conditions of existence entail real political power? Do we now find ourselves in a situation where Eco’s “Return of the Middle Ages” presaged not an abstraction but the emergence of an actual politics of feudalism, marked by relations of fealty and deference, connections of blood kinship, and divisions of friend and enemy?

II. Court and Keep

The historicism of Trump’s world begins, like the “medieval revival” in architecture, in a syncretic mode.5 Upon arriving at the entrance of Trump Tower after its completion in 1982, Eco would have encountered a doorman dressed in an elaborate “British” military costume, complete with tasseled epaulettes, gold cord frogging, a bear-skin hat, and white gloves. Trump and his first wife, Ivana, commissioned these outfits directly from Savile Row tailor Dege & Skinner for their entire regiment of concierges and elevator attendants, combining elements of fifteenth-century Tudor yeomen’s uniforms with those of eighteenth-century cavalry officers and nineteenth-century grenadiers, as well as invented collar medallions bearing a custom Trump insignia.6

Though Trump Tower was constructed during the heyday of postmodern skyscrapers, when quotations of historical styles were often incorporated directly into the façades of buildings as ornament, here, this work of bricolage is assigned to the guards, leaving the uniform black curtain wall intact.7 In the sartorial assembly of the guards’ costumes, we are meant to recall the trappings of an ahistorical though specifically British monarchy, lending the entire concrete structure the status of a protected royal property.

Even as the tower was under construction in 1981, a rumor circulated through the local press that the British Royal Family was considering purchasing the twenty-one-room penthouse apartment that would later become Trump’s primary residence. Although this report was dismissed by Buckingham Palace, it continued to appear within the pages of the New York Times, corroborated by an anonymous “real estate official.”8

Trump refused to either confirm or deny the report, extending its life through suggestive but ambiguous remarks—a strategy he honed during those early years but one that has produced more corrosive and consequential results during his political career, when such remarks have gone beyond hinting at celebrity investors and tenants, instead calling into question the birthplace of elected officials, the motives of entire religious groups, and the veracity, or lack thereof, of the free press. In this context, the condominium structure of the building and the necessity of preselling units offered yet another occasion for embellishment. Through costumes and planted rumors, an imaginary “courtship” of Princess Diana in the 1990s, and the appropriation of Scottish heraldry for the logos of his international golf resorts in the 2000s, Trump’s persistent overtures to the British throne reveal an ongoing desire to merge his brand with Anglo-Saxon nobility.9

As such, it is not so surprising that Eco would draw upon these explicit monarchical references when interpreting the tower as a castle, and Trump as another American Hearst figure, hoarding copies of European originals in a fruitless quest for authenticity. However, in stratifying the tower into the medieval categories of court and keep, Eco crucially misreads the property lines of the building, following the signs of feudalism up to Trump’s penthouse apartment rather than down to the commons of the sunken atrium.

Beginning with the city’s 1961 zoning ordinance, the creation of privately owned public spaces (POPS) allowed developers in New York City to bypass height and setback restrictions in high-density areas in exchange for the inclusion of publicly accessible plazas, atria, and arcades on the ground level.10 At Trump Tower, this public-private tradeoff, alongside the purchase of air rights from the neighboring Tiffany’s building, permitted Trump and his architect, Der (formerly Donald) Scutt, to add twenty floors of office and residential space in return for the construction of the six-story atrium, two gardens, restrooms, and public seating.11 The building is, therefore, organized around a deal: Trump’s share consists of the additional upper stories of the building, granted on the condition that these public spaces, concentrated in the lower part of the building, are both maintained and accessible.12

Though the status of POPS has become a point of controversy and debate in New York in more recent years—through the occupation of Zuccotti Park in 2011 and efforts by local activists to show how the private maintenance of these spaces often falls short of what is required by the zoning ordinance—the public stake in Trump Tower was suppressed in the presentation and reception of the building at the time of its construction, as the tower and atrium space were more often framed in the language and imagery of conspicuous beneficence.

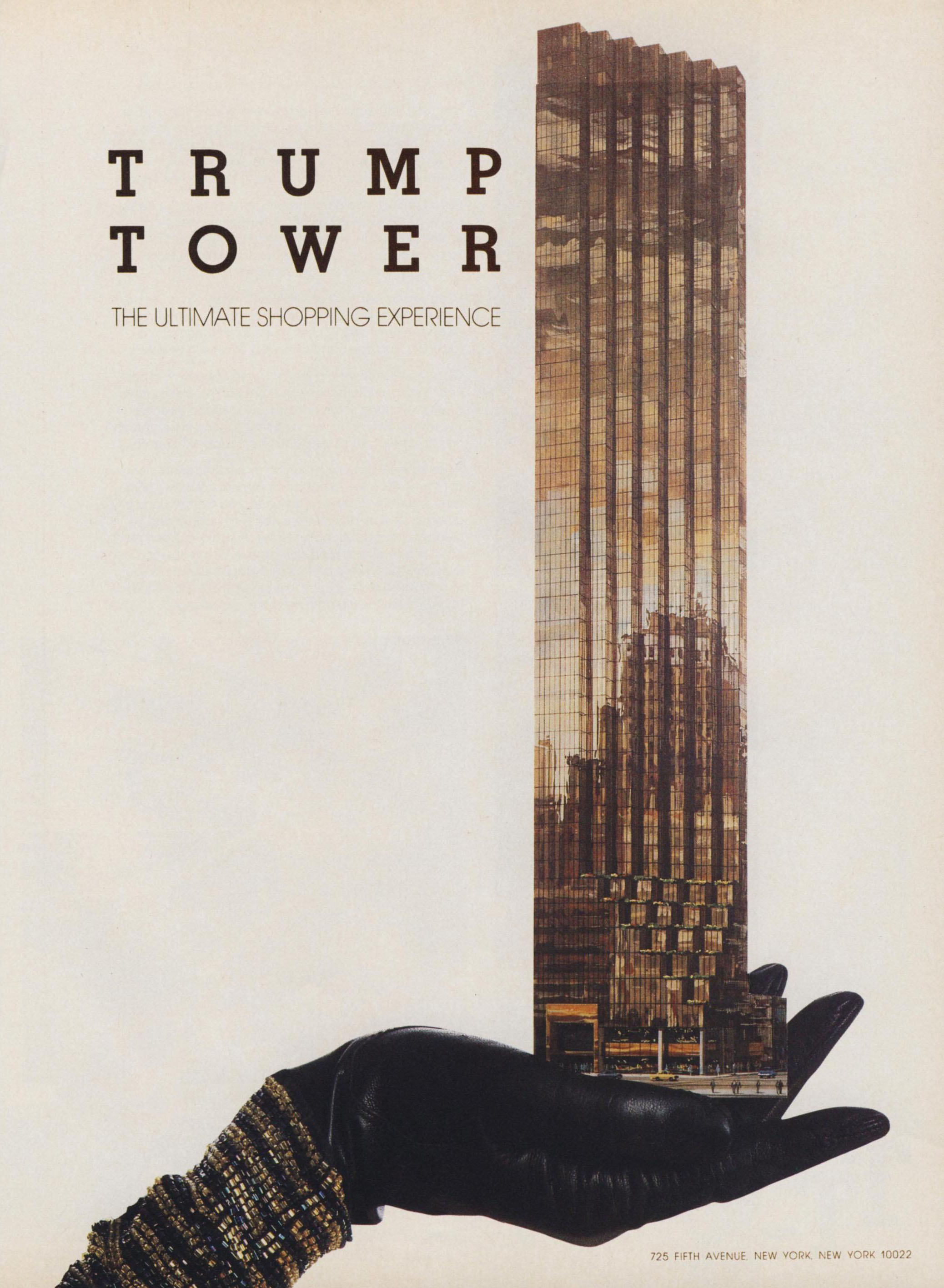

A collaged advertisement for Trump Tower from 1983, published in a multi-page insert in Vogue, allegorizes the air rights purchase from Tiffany & Co. as an offering on the part of the jeweler. The tower appears in miniature form, extending from the palm of an outstretched, leather-gloved hand, connected synecdochically to Tiffany & Co. via Audrey Hepburn’s evening-turned-morning-wear. The proportions of the tower have been exaggerated with the removal of horizontal mullions, and the addition of floors in order to correspond to Trump’s inflated, and self-evidently false, claim that the building is actually sixty-eight stories high.

Here, the black mirror glass of the façade has been tinted into a warmer color and the saw-tooth extrusions and stepped-back terraces on the lower level suggest angled incisions made in precious stones—an effect made more explicit in the advertising copy on the following page in which the tower is described as a “multi-faceted gemstone,” surrounded on twenty-eight sides by a material that is imaginatively named “jet-bronze glass.” In this idealized representation, the tower’s literal concrete structure is rendered through its surface material as a kind of crystal, one that both concentrates and emits value while carrying the potential for unlimited, spontaneous growth.

In a review of the tower from the same year titled “Atrium of Trump Tower is a Pleasant Surprise,” New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger extends the material fetishization of the Vogue advertisement into the interior of the building, where he writes that the pervasive finish of breccia pernice marble “gives off a glow of happy, if self-satisfied, affluence” to tourists and shoppers in the lower galleries.13 Though Goldberger criticizes the overall profile of the building and mirrored glass façade, concluding that “in the process of achieving a balance between a building’s public presence and its private one, the decision was made to make the private presence paramount,” he omits the reciprocal relationship between the additional leasable floors and the atrium, expressing sympathy instead for the architect who must mediate between the contradictory demands of public and private interests and the famously bad taste of the client.14 Goldberger is surprised not by Trump’s ability to maximize the square footage of the tower but by his formal restraint, expressed as a kind of unexpected generosity.

If Goldberger’s reaction to Trump Tower could be understood as a form of aesthetic relief—he admits at the outset that “it has not been difficult to presume that Trump Tower…would be silly, pretentious, and not a little vulgar”—then mayor Ed Koch’s reception of the tower was framed in more explicitly transactional terms. In local news footage of the topping off ceremony from July 27, 1982, Koch, who had been in such a hurry to get to the event that he struck a woman with his car and kept driving, speaks indirectly to and for the television audience: “On behalf of seven and a half million New Yorkers, you’re bringing a lot of money into the city, and that helps us to deliver services.”15

Enter, once more, medieval metaphors, not British this time but specifically Irish. In the presence of Trump’s developer father, Fred, Koch delivered a direct appeal to Trump’s own fascination with heraldry and heredity through, what he described as an “Ancient Irish Toast to the Lord of a Newly Built Castle”: “May these walls withstand the winters of endless years,” he proclaimed, turning to Trump. “May all who dwell within know only happiness, and may the windows of the building forever look out upon a place of peace and prosperity.”16 In Trump’s expression of gratitude, “Very nice, very, very nice,” he seems to have recognized the passage of his rumored affiliation with royalty into stated fact. The topping off ceremony, which is itself rooted in the rituals of medieval construction, here becomes a site of a renewed invention of tradition.17 And yet, in this recognition, Trump fails to recognize the way in which Koch, through his capacity as a democratic representative and invocation of the entire population of New York, throws his own noble imposture into relief.

III. Rogata’s Attempt

Arriving at Trump Tower today, one is greeted not by faux British grenadiers but by three types of police: Secret Service agents, Trump Tower guards, and New York Police Department personnel—each with separate but overlapping jurisdictions. Unlike their 1980s predecessors, the Trump Tower guards have gone undercover with dark suits and earpieces, now resembling Hollywood versions of the Secret Service. The real Secret Service agents are dressed in black bulletproof vests, clearly labeled with their occupation. Once tenants of Trump Tower, they now occupy a trailer on Fifth Avenue, due to the prohibitive cost of the rent; a rare instance in which Trump’s landlord/president emulsion proved insoluble. The NYPD detail assigned to the tower is the most heavily armed and the most visible from the exterior of the building, since they patrol a barricade that stretches along Fifth Avenue and across Fifty-Sixth Street, occasionally bolstered by a convoy of sand-filled sanitation trucks during periods of high alert.

If the Trump Tower of the 1980s was recognized as a castle through its allusions to monarchy and symbolic status, these ad hoc security measures transform the building more directly into a working fortification in the present day, recalling the emergence of the castle type within feudalism as the communal urban defenses of late antiquity broke down and were gradually replaced by private strongholds in the countryside.18 In the militarization of the tower, the double exposure of the step-back façade—once marketed as a real estate amenity in the offering of not one, but two privileged views—displays the basic principle of flanking, common to both battle formations and fortifications that were meant to draw the enemy farther into a line of defense in order to expose their more vulnerable sides to attack.

This strategy was employed to great effect in August 2016, when Virginia teenager Stephen Rogata attempted to scale the exterior of the tower using suction cups and a harness. Rogata was seized by police and hoisted through an open window on the twenty-first floor before he could reach Trump’s office on the twenty-fifth floor. Though live coverage of this event on cable news channels quickly moved from breathless alarm to comedic narration, as the stunt was revealed as a parody of a siege, Rogata would claim in a retroactively posted video that he had simply wanted to deliver a private message and had hoped that Trump would be impressed by his entrepreneurial spirit.

Rogata’s attempt would then foreshadow the parade of opportunistic visitors from the realms of politics, business, and entertainment, who arrived in the lobby of Trump Tower in the days following the November 2016 election, each seeking an audience with the country’s newly ascendant president elect. News cameras stationed in front of the elevator doors captured the entry and departure of these summoned guests from across the political spectrum, as the lobby functioned as an antechamber, with the duration of waiting indexing the perceived importance of the visitor. Reemerging from the elevator, many of these guests would approach the press pool, offering assessments of meetings that were, without fail, “very productive.” Productive of what? In this period of transition, Trump is conspicuously absent from the stage. However, each entrant into the lobby seems to further increase his authority, elevating what had already been escalated in his improbable announcement in June 2015. In the interstices between the meetings, the cameras continue to roll, trained upon the closed elevator doors and the idle concierge. Watching this footage remotely, the television viewer waits as well in helpless anticipation.

Crenellated towers, treasure troves, fortifications, guards at arms, audiences of supplicants—all are indications of a medieval, and specifically feudal, paradigm. Yet the revival of medievalism within architecture has a much longer history that has often countered the development of an alienating industrialism and imperialism—those very sources of power that Trump pursues—even as medieval styles have, at other turns, been called upon to spiritualize capital at the nexus of commerce, governance, and religion.19 In the eclecticism of Walpole, the moralism of Pugin, the artisanalism of Ruskin, the utopianism of Morris, and the rationalism of Viollet-le-Duc, we witness an array of programs in which medieval sources are both idealized and employed toward ideological ends. And yet, in each of these cases, the referent remains at a distance—the historical dissonance is out in the open. As Trump’s medievalism has evolved, it has become clear that he is attempting to realize the fantasy, to literalize the allusion. In this sense, the medievalism of Trump Tower is not a revival at all but a lived historical reality that is only now coming into focus.

-

Alan Taylor Communications, “Pitney Bowes Teams Up with Influential Personalities for Worldwide ‘Pushing the Envelope’ Literacy Campaign,” September 7, 2005, link. ↩

-

Trump’s de-emphasis of the context of the tower is typical among his limited set of architectural sketches. In an additional sketch of the Empire State Building from 1990, auctioned in 2017, the tower is rendered as isometric, projected from a scribbled ground plane that merges with his signature. ↩

-

Trump’s “elevated” perspective is, perhaps, best recognized in his irregular speech that veers wildly between speculative warnings and promises as if he is scanning the horizon for both dangers and opportunities. ↩

-

Eco’s observations come from the first of two essays on this subject, from 1986 and 1996, since republished together in the American collection of his articles, essays, and columns, Travels in Hyperreality, under the heading “The Return of the Middle Ages.” Umberto Eco, “Dreaming of the Middle Ages,” in Travels in Hyperreality (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014), 62. Eco’s medieval reading of this postmodern lobby stands in stark contrast to Fredric Jameson’s contemporaneous tour of the Westin Bonaventure in Los Angeles, where he famously found in the hotel’s cavernous interior, artificial lake, and elaborate modes of vertical circulation a futuristic “hyperspace” that had finally “transcended the capacities of the individual human body to locate itself.” ↩

-

Horace Walpole’s eclectic Strawberry Mansion, which began construction in 1749, is often cited as a starting point for the history of medievalism in architecture, soon displaced by the archaeological and moral purity of Augustus Pugin in the nineteenth century. John M. Ganim, “Medievalism and Architecture,” in The Cambridge Companion to Medievalism, ed. Louise D’Arcens (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2016). ↩

-

The details of the guards’ tunic and frockcoat uniforms are described on the website of the tailor: “Towering Uniforms,” January 2017, link. ↩

-

Paul Goldberger, one of the only critics to address the work of the architect of Trump Tower, Der Scutt, would identify the building in the early 1980s as one of the “New American Skyscrapers” that used setbacks, and “crisp diagonals” to allude to historical styles without the direct application of ornament. Paul Goldberger, “The New American Skyscraper,” the New York Times, November 8, 1981, link. Writing on the architecture of his teacher and employer, Paul Rudolph in 2001, Der Scutt would cite the “sculptural crenellations” of Rudolph’s towers as the source for his own approach to high-rise massing. Der Scutt, “Paul Rudolph,” in Architects on Architects, ed. Susan Gray (New York: McGraw Hill, 2001), 181. ↩

-

Albin Krebs and Robert McG. Thomas Jr., “Notes on People; A Condominium for the Royal Family?” the New York Times, August 4, 1981, link. Barbara Res, the construction manager for Trump Tower, strongly suggested in recent correspondence that “real estate official” was Trump himself: “I can’t state with absolute certainty that the story was a plant, or as we Americans might say, 100 percent bullshit, but I would put a lot on that bet.” Barbara Res, email message to author, January 2, 2018. ↩

-

Danny Hakim, “The Coat of Arms Said ‘Integrity.’ Now It Says ‘Trump,’” the New York Times, May 28, 2017, link. ↩

-

The City of New York: Zoning Maps and Resolution (1961), link. ↩

-

Jerold Kayden, Privately Owned Public Space: The New York City Experience (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2000), 132. ↩

-

This seemingly straightforward allotment of public and private space does not, however, map onto the tower’s actual distribution of ownership since each condominium belongs to a separate individual, partnership, or corporation, which are themselves composed of innumerable numbers of stakeholders. In a report of current mortgages in the tower, compiled by real estate intelligence firm Actovia and shared with the author, the only lot within the building that is registered under Trump’s personal name is his 6,096-square-foot residence divided between the fifty-sixth, fifty-seventh, and fifty-eighth floor, amounting to less than 1 percent of the total square footage in the building and far less than the 33,000 square feet that he has claimed publicly. ↩

-

Paul Goldberger, “Architecture: Atrium of Trump Tower Is a Pleasant Surprise,” the New York Times, April 4, 1983, link. Though Goldberger’s review was decidedly mixed, the more positive quotes were nevertheless posted on a wall facing the interior courtyard of the tower under the headline, “Rave Reviews from the Critics,” in 1983. His senior colleague, Ada Louise Huxtable, whose praise for the proposed tower was included among this collection of taglines, would write a correction in the New York Times in the following year, criticizing the realized façade as “dull and ordinary” and the lobby as “uncomfortably proportioned” and a “pink marble maelstrom.” Ada Louise Huxtable, “Donald Trump’s Tower,” the New York Times, May 6, 1984. Though many of these early critics dismissed the tower on aesthetic grounds, the architectural historian Diane Ghirardo would read the tower in the late 1980s as symptomatic of wider processes of gentrification, rising income inequality, and the “dehumanization of American cities.” Diane Ghirardo, “Tower of Trumped-Up Power,” the Architectural Review, vol. 184, no. 1098 (August 1988). Since the 2015 campaign, architectural critics and historians have returned to the tower in order to reassess its position within Trump’s political program. See Michael Sorkin, “The Donald Trump Blueprint,” The Nation, (August 15–22, 2016). Others have situated the entirety of Trump’s “performed reality” within a longer history of coded speech acts. See Reinhold Martin, “The Demagogue Takes the Stage,” Places Journal (March 2017), link. ↩

-

Goldberger, “Architecture: Atrium of Trump Tower Is a Pleasant Surprise.” ↩

-

“Archival Video: July 27, 1982: Donald Trump Celebrates Completion of Trump Tower,” ABC News, link. The toast was inserted into Koch’s remarks by his speechwriters Clark Whelton and Atra Baer from a book of Irish quotations in the days leading up to the event. Clark Whelton, email message to author, April 11, 2018. ↩

-

Jonathan Mandell and Sy Rubin, Trump Tower (Secaucus, NJ: L. Stuart, 1984), 7. ↩

-

See, for example, G. W. Speth’s compilation of medieval “completion-sacrifices,” in G. W. Speth, Builders’ Rites and Ceremonies: Two Lectures on the Folk-Lore of Masonry (Margate, Eng.: Kebble’s Gazette Office, 1894). Hugh Trevor-Roper published his classic study of the Highland Tradition in the same year as the tower’s opening, demonstrating how the most recognizable Scottish cultural forms—family tartans, the Scottish kilt, and Scots-Gaelic epic poetry, for example—were largely fabricated during the eighteenth century by a few enterprising nationalists. This work also helps to show how Trump’s specifically “Scottish” allusions were invented from the outset. Hugh Trevor-Roper, “The Invention of Tradition: The Highland Tradition of Scotland,” in The Invention of Tradition, eds. Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1983). ↩

-

R. A. Stalley, Early Medieval Architecture (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1999), 83. As Michael Lewis has shown, the military use of castellated structures persisted well into the eighteenth century in Scotland, even as the Gothic revival began as a symbolic, revivalist practice elsewhere in England. Michael Lewis, The Gothic Revival (London: Thames and Hudson, 2002), 28. ↩

-

See, for example, Friedrich von Schmidt’s Rathaus in Vienna (1872–1883), which was constructed in a Gothic style in the mid-nineteenth century through the patronage of burghers and merchants in order to recall the Vienna commune and medieval peasant revolutions while opposing the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Cass Gilbert’s Woolworth Building, consecrated as “The Cathedral of Commerce” by the Reverend S. Parkes Cadman in 1912, serves here as an example of the latter tradition and a predecessor of Trump’s Manhattan medievalism, along with Le Corbusier’s 1936 New York reverie, written with “a heart full of the sap of the Middle Ages.” Le Corbusier, Quand les cathédrales étaient blanches: Voyage au pays des timides (Paris: Librairie Pion, c. 1937). ↩

Samuel Stewart-Halevy is a doctoral candidate in the history and theory of architecture at Columbia University.