I

If someone offered you $50 million for the air around you, would you take it? Take a deep breath. When we notice the air around us, we recognize its potency. We are, of course, always breathing it in. But generally we exist in air without recognizing it as such. How do we value our air?

In the summer of 2018, residents of New York City’s Seward Park Cooperative faced that question, when the complex was offered $54 million for its air rights. Ascend/Optimum group, the developers making the offer, hoped to acquire the air rights above and around the complex. The deal would allow them to increase the height of their planned development—two sleek, glass towers on the edge of the co-op’s lot, flanking the former Bialystoker Nursing Home—from twenty-two stories to thirty-three.1 The Seward Park Cooperative, in need of capital for building repairs, weighed its options. The co-op, constructed in 1960 as a middle-income housing development, is comprised of four utilitarian brick buildings situated on a thirteen-acre lot nestled between the Lower East Side and Chinatown in Manhattan. The project was financed largely by labor union pension funds, modeled after nearby union-funded housing cooperatives—the Hillman Housing Cooperative (completed in 1950), and the East River Housing Corporation (completed in 1956).2 Herman Jessor, Seward Park’s architect, was closely associated with the cooperative housing movement in New York. The buildings’ current tenant composition, a mix of aging longtime residents (the co-op has been labeled a “naturally-occurring retirement community,” or NORC) and young new-arrival families, reflect the neighborhood’s long transition from the solidly immigrant community of the early twentieth century to an epicenter of blue-chip art galleries today.3 Up the block from Seward Park Cooperative, Essex Crossing, a 1.65-million-square-foot mixed-use mega-development currently in construction on city-owned land, marks the culmination of the city’s fifty-year redevelopment plan of the so-called Seward Park Urban Renewal Area.4 It is against this backdrop that the air around Seward Park is so valuable—to the developers, eking the most square footage out of a dwindling stock of buildable city land, and to the tenants, with a vested interest in the shape of their neighborhood. In a narrow and contested vote, the members of the financially burdened co-op decided to reject the money, in favor of their air.

Right: Rendering of proposed towers surrounding Bialystoker Nursing Home building by Space4Architecture [S4A]. © S4A.

II

Cuius est solum ejus est usque ad coelum et ad inferos.

For whoever owns the soil, it is theirs up to heaven

and down to hell.5

The notion of “air rights” as a legal concept is said to begin with the above legal maxim on land ownership. The maxim, dating to the thirteenth century, codifies the space of terrestrial ownership within a sub- and extraterrestrial plane. Its original purpose was to designate burial space free from overhangs.6 Generously, the maxim refers to heaven and hell—wherever the soul of the individual rests in perpetuity is God’s will, but property rights are property rights. If at some point property ownership was thought to extend from the fiery inferno at the earth’s core, through terra firma, and up to the far reaches of the galaxy, its upper and lower limits have certainly been problematized. Particularly with the advent of the airplane, the very idea of airspace became a contentious one. In the mid-1940s, Thomas Lee Causby, a chicken farmer outside Greensboro, North Carolina, complained that airplanes flying over his farm were frightening his chickens, even scaring them to death. Causby sued the federal government over his deceased animals and failing business, arguing that the “cuius” maxim of land ownership meant his chicken farm reached up to the heavens. While the Supreme Court rejected this ancient notion of ownership (it “has no place in the modern world”), it ruled that “if the landowner is to have full enjoyment of the land, he must have exclusive control of the immediate reaches of the enveloping atmosphere, free from any ‘direct or immediate interference.’”7 Thus was enshrined into contemporary law a basis for air ownership, albeit with nebulous parameters.

III

Capitalism succeeded in what has so far only been a dream of science-fiction writers: teleporting the wealth from the future to the present.8

—Agnieszka Kurant

The modern practice of buying and selling air rights began in the early twentieth century with the development of New York’s Grand Central Terminal. In 1899, Cornelius Vanderbilt named William Wilgus chief engineer for the new station—and, together, they embarked on their grand plan to modernize the existing train system. As trains switched over from steam to electric power, train tracks could be placed belowground. Wilgus planned and built Grand Central as an underground network of electrified tracks, platforms, and train yards. The concourse would remain at ground level to direct passengers.9 With the majority of the project nestled below street level, Vanderbilt and Wilgus recognized the underutilized, developable space above their parcel of land. Wilgus conceived of a twelve-story, profit-generating building above the terminal: “Thus from the air would be taken wealth,” he wrote.10 Though the building atop Grand Central Terminal would never be built, the Wilgusian idea of monetizing air engineered a new profit model for real estate development that would mark the coming century.

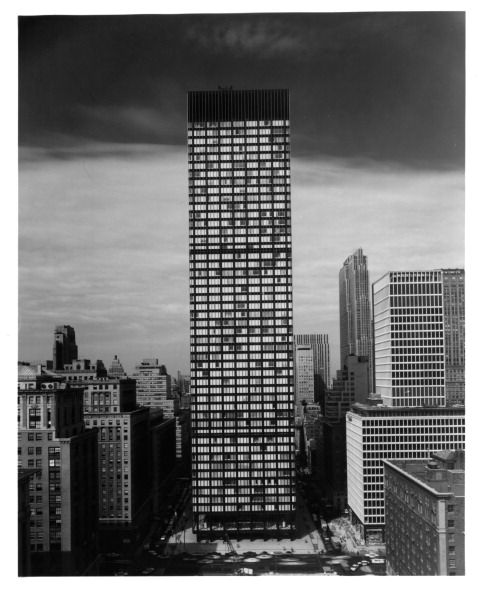

Every city lot has a maximum buildable potential based on its zoning, and air rights, or transferable development rights, demarcate the unused potential. The exchange of this unused buildable potential effectively allows property owners to increase the building envelope beyond the zoned capacity of a lot. The practice of transferring air rights between adjacent properties was written into New York City’s first zoning ordinance in 1916. A 1961 revision of the zoning ordinance expanded the process of acquiring and applying air rights, allowing property owners to transfer air rights between noncontiguous lots in specially zoned districts and landmarked sites.11 By the 1960s, air rights transactions had begun to enter into common practice, at which point they became, as Wilgus predicted, “a gold mine, so to speak.”12 Real estate developers became alchemists; air was transfigured into real, fungible capital. This capital, and its material form, square-footage, began to circulate lot-by-lot throughout the city. According to a report on air rights published by the American Planning Society in 1964, more than one hundred air rights transactions had been litigated in New York and Chicago in the previous year alone. And the phenomenon was not limited to these two major urban centers. The report also listed air rights transactions in Cleveland, Ohio; El Paso, Texas; Hollywood, Florida; and Sioux Falls, South Dakota.13 In most of these projects, air rights were transferred from public infrastructure projects (railroads, highways, parks) in exchange for private development (offices, commercial space, residential buildings). This kind of public-private exchange ensured that public works projects would not slow down private development but actually incentivize it. In 2005, New York City willed the High Line into existence through this provision, enabling the sale of air rights around the disused elevated railway in the special rezoned West Chelsea district.14 Alongside the city’s newest and sleekest park rose numerous luxury properties, bolstered in bulk and value by those newly exchangeable air rights.

A similar mutually beneficial arrangement emerged in the practice of selling air rights for landmarked buildings in order to preserve historic, often low-rise buildings without curtailing the forward (and upward) thrust of development. This practice continues to be an effective leveraging tool for landmarked buildings. In summer 2018, Manhattan’s historic St. Bartholomew’s Cathedral contracted to sell fifty thousand square feet of undeveloped air to banking giant JPMorgan Chase for $20.7 million.15 St. Bartholomew’s newly acquired capital will allow the romanesque revival church to make necessary renovations to their building. In December 2018, JPMorgan acquired an additional 666,766 square feet of air rights from Grand Central Terminal for a total price of $208 million, of which 5 percent of the purchase price, or $10.4 million, is required to be used to preserve the landmark terminal in good condition.16 JPMorgan will transfer their newly acquired speculative development rights down the block to 270 Park Avenue, where SOM’s fifty-two-story modernist tower, the Union Carbide building, currently stands. The bank plans to tear down the existing building (notably, one of the few woman-designed modernist office towers in the city) to make way for a new headquarters. The new building is intended to be seven hundred feet taller and a million square feet bigger than the current building, an achievement made possible only through air rights acquisition and transfer. If demolished, Union Carbide would be the largest building ever voluntarily torn down, raising concerns over not only the historical significance of the current building but also the environmental dubiousness of such a demolition.17 A recent upzoning of the Midtown East district paved the way for JPMorgan’s redevelopment plan. In this regard, JPMorgan’s deal represents the city’s zoning and development apparatus functioning exactly as it was designed to do: a massive corporate real estate project made possible by acts of preservation in the name of public service. In deals like these, important city functions become outsourced to private entities, leaving the shape of the city at the whim of the corporate bottom line.

IV

Providing us with an invisible dwelling wherever we are or go, air is also a faithful companion for the one who can pay attention to its invisible presence.18

—Luce Irigaray

The monetization of air into square feet is not only the logical extension of contemporary neoliberal real estate development but also the product of a much larger narrative of human-atmospheric relations that emerged in the twentieth century. According to philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, the twentieth century marked the “explication” of air—a newfound awareness of our being-in-the-environment as such. He pinpoints this moment of explication to April 22, 1915, when German soldiers perpetrated the first act of gas warfare and turned the environment into a weapon and the breather into a victim. In doing so, gas warfare created an intellectual dissociation whereby what was once imperceptible becomes simultaneously apparent and deadly.19 Once air becomes a weapon, it also becomes an aesthetic object. The proliferation of air conditioning marked the rise of “designer air.” Buildings could be eminently climate controlled, therefore redefining the design and occupation of interior space and our relation to the outside.

If for most of human history, the ability to breathe was taken for granted, breathing in the twentieth century became nothing short of precarious. Gas warfare is one instance of this, but air pollution has become a much more acute threat to human breathing. The environmentalist movement that gained traction in the early 1960s did so with an increasing awareness of the harmful effects of pollution. While the origins of environmentalism are often associated with a free-flowing California hippie culture, there was a more straight-laced campaign in the environmental economics sector. While the hippie environmentalists were busy questioning the status quo of life on earth, their free-marketeer counterparts were conducting cost-benefit analyses of environmental degradation.20 When the Clean Air Act was passed in 1970 (a law that, until key parts were recently dismantled by the Trump administration, was widely heralded as one of the great legislative victories for the environmental movement), the Nixon administration couched the legislation in terms of its economic, rather than environmental, benefits.21 Since then, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has packaged their policy directives according to economic valuation.22 In a contemporary context, the conversation around environmental policy seems to begin and end with carbon tax proposals. When the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a group of UN-affiliated scientists, issued its report about the imminent devastating effects of global warming, the authors insisted the only hope for mitigating an impending climate catastrophe would be to levy heavy and widespread taxes on carbon emissions.23 Call it pragmatism or call it cynicism, air is a precious commodity, and the market-based approach to climate change has named it as such.

Most certainly, as is clear in the notion of environmental economics as well as air rights, there is a gap between the valuation of air and actually valuing air—the gulf between air’s potential financial liquidity and its simultaneous status as the fundamental sustainer of life on earth. Is this a simple distinction between use-value and exchange-value? The financialization of air seems to elude such a simple designation, precisely because air itself is so omnipresent and so elusive. Underlying the concept of air rights in real estate development is the notion of absence. For air rights to be valuable, space has to be empty, unfilled, unused. Air rights are about speculation, taking what does not exist and imagining what could be filled in. Perhaps most crucially, air rights, and the act of ascribing capital to air, can reiterate the presence of air rather than the absence of building. We might ask, who possesses the right to air?

For Sloterdijk the technological manipulation of air from air conditioning to olfactory comfort to produce “psychoactive breathing environments” condemns our environmental relationship to the logics of consumerism. This sort of techno-environmental apparatus prefigures how we can relate to the atmosphere at all. One could argue that the relegation of air to a commodity within the real estate market is a logical extension of the climate-controlled building envelope. Historicizing this argument, one might even point out that the invention of air conditioning, and its increased usage as the curtain wall took its architectural prominence, maps neatly onto the lineage of air rights development. Air rights transactions literally renegotiate the space between interior and exterior air. While Sloterdijk’s argument that interior atmospheric control has supplanted our experience of air altogether lends itself to understanding the figure of air in the real estate market, it does not account for those calling for ecological accountability. The financialization of air embedded in carbon tax proposals aligns with Sloterdijk’s recognition of the atmosphere as a free-market frontier; however, his cynicism about the technopolitics of life overlooks the strong desire to preserve our air-out-there. As a means to expand the volumetric envelope of a building, air rights may be instrumental in shaping the built environment and bolstering the real estate market. But they do not say much about the larger question of air. Where air rights concern themselves with the optimization of buildable space, the right to air is about the viability of life.

V

Sell the Air Right—Mineral and water to your truck.

Exercise your air rights

Comb your heir rights.

A comfortable place to live between the bricks.

Ash-Track

An Abstract A (the History of property.)24

—Gordon Matta-Clark

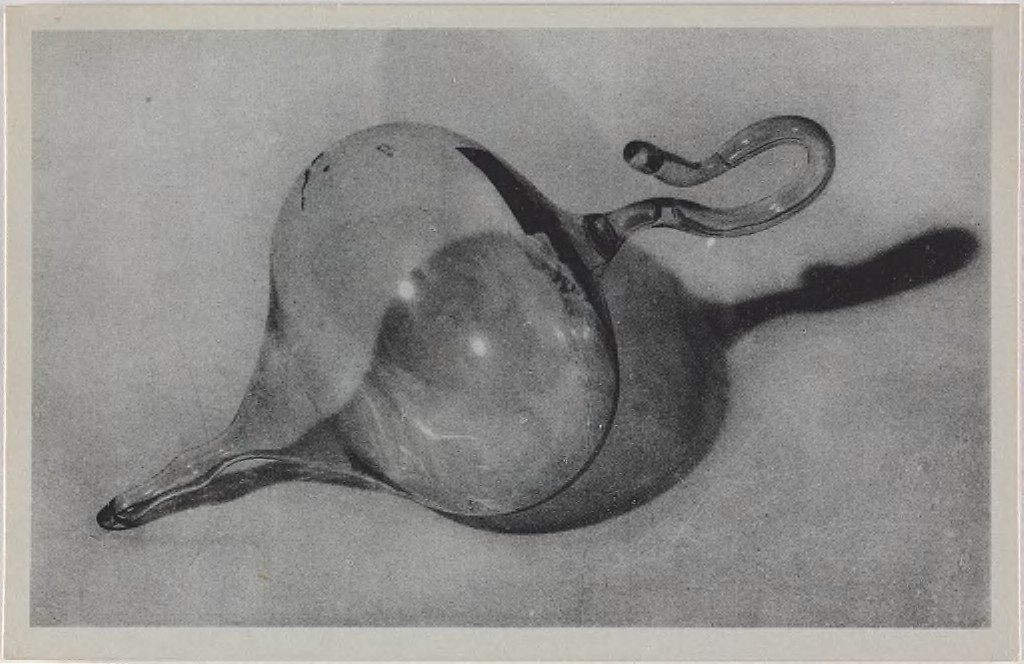

In 1919, Marcel Duchamp purchased a serum ampule at a pharmacy, instructing the pharmacist to pour out the contents and then reseal the empty container. He brought the ampule back to the United States with him, gifting it to his patron Walter Arensberg with the inscription, “50 cc air de Paris.”25 This became one of Duchamp’s first ready-mades, and it perfectly encapsulates the Dada gesture. What’s more abundant, mundane, and emphatically not art than air? In Sloterdijk’s retelling of Duchamp’s process, the ready-made has a more apocryphal origin. Apparently, Duchamp’s pharmacy, and thus its air, was not in Paris at all, but in Le Havre along the coast in northern France. Regardless of its supposed misnomer, the act of bottling, naming, and then gifting air to his collectors, turned the air into a work of art. In an interview, Duchamp described the intention behind his readymades as an attempt to “get out of the exchangeability, the monetization, one might say, of the work of art.”26 Of course, an art market built upon speculation and exchange value holds no such artistic intentions sacred. In 2016, an edition of Air de Paris sold at a Christie’s auction for $845,000.27

In March 2015 eBay user stangeedon1 listed a sealed Ziploc bag with “AIR FROM KANYE SHOW” written in Sharpie across the front of it. Stangeedon1 titled his post “Kanye West Yeezus Tour Air For Sale” and set the opening bid at $5. A day later, eager fans had bid up to $60,000 for the bag of Kanye air.28 Just imagine stangeedon1, waving a sandwich bag above their head as Kanye West performs onstage. While there is no way to tell how proximal the bag ever was to Kanye, or if it was ever even inside the stadium (Duchamp’s Air de Paris never saw Paris, after all), internet sleuths were able to verify that stangeedon1 was located in the same city as the Yeezus tour that day. Maybe that was enough. The incident probably tells us more about the enduring reign of one of the most successful and enigmatic artists of our time, the entrepreneurial spirit of his fans, and viral meme culture than it does about air per se. However, it does demonstrate (in its echoing of Duchamp) that for all the attention we don’t pay to it, we do, deep down, recognize that air holds something special, whether the presence of a contemporary genius or the genius loci of a city. And what’s more, we are all too eager to make a quick buck off of it.

“If air is crucial for life,” philosopher Luce Irigaray writes, “it is also essential as a fluid to ensure the cohesion of a physical and even a spiritual whole, be it individual or collective. If we were capable of forming every whole while taking air into account, our totalities would lose their systematic and authoritarian nature.”29 Irigaray sees air as the interface between oneself and everything around us. It is not so much buildings or borders that hold us in space; it is air. Our atmospheric conditions register our being-in-the-air, and really, our being-in-the-world. When the residents of Seward Park Cooperative put the sale of their air rights to a vote, the community was bitterly divided. When the sale was rejected for failing to get a two-thirds majority vote, a group of shareholders began to petition for an additional vote to reverse the decision.30 If, following Irigaray, air has the potential to cohere communities, then the financialization of air might instill the opposite effect. While the practices of financializing air, from air rights to carbon taxing, from modern art to a contemporary internet troll, insist that air is valuable, high valuation usually indicates scarcity. If we keep kicking the bucket down the road, it appears we might be in for austerity of air. Instead, as Matta-Clark says, let’s exercise our air rights, flex our atmospheric belonging, and take the financial hit.

-

Charles V. Bagli, “A $54 Million Offer to Build Oversize Towers Divides Seward Park,” the New York Times, June 10, 2018, link. ↩

-

Gabrielle Bendiner-Viani, “Layered SPURA: ‘Unless It’s Written It Never Happened,’” in Contested City: Art and Public History as Mediation at New York's Seward Park Urban Renewal Area (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2018), 16. ↩

-

Tobias Armborst, Georgeen Theodore, and Daniel D’Oca, “NORCS in New York,” Thresholds 40 (2012): 189–208, link. ↩

-

In the 1967, the city razed the site as part of the Seward Park Slum Clearance project, displacing a largely working-class Puerto Rican population living there. The site remained vacant until 2013, when the Bloomberg administration brokered a deal to develop the lots. SHoP Architects are overseeing the nine-building development project, expected to be completed in 2024. See Eugene Chen, “The Seward Park Urban Renewal Area, Forty-Five Years Later: Affordable to Whom?” CUNY Law Review, vol. 18, no. 2 (April 2015): 2, link; and NYC EDC, “Essex Crossing Development (Seward Park),” link. ↩

-

Byron K. Elliot, “Law of the Air,” Indiana Law Journal, vol. 6, no. 3 (December 1930): 168, link. ↩

-

Elliot, “Law of the Air,” 168. ↩

-

Amy G. Richter, “Grand Central’s Engineer: William J. Wilgus and the Planning of Modern Manhattan by Kurt C. Schlichting (review),” Technology and Culture, vol. 54, no. 3 (2013): 670. ↩

-

Sam Roberts, Grand Central: How a Train Station Transformed America (New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2013), 112. ↩

-

New York City Department of City Planning, “A Survey of Transferable Development Rights Mechanisms in New York City,” February 26, 2015, link. ↩

-

Roberts, Grand Central, 120. ↩

-

Leopold A. Goldschmitt, “Information Report No. 246: Air Rights,” American Society of Planning Officials (1964), link. ↩

-

New York City Planning Commission, “West Chelsea Zoning Proposal,” June 23, 2005, link. ↩

-

Sydney Franklin, “Historic Midtown NYC Church to Transfer Air Rights to JPMorgan,” the Architect’s Newspaper, October 3, 2018, link. ↩

-

Kathryn Brenzel, “JPMorgan Buys 667K sf of Air Rights from Grand Central for 270 Park,” the Real Deal, December 13, 2018, link. ↩

-

Mackenzie Goldberg, “Citing Environmental Concern, AIANY Expresses Worry over the Demolition of SOM’s 270 Park Avenue,” Archinect News, April 2, 2018, link. ↩

-

Luce Irigaray and Michael Mardar, Through Vegetal Beings: Two Philosophical Perspectives (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016), 28–29. ↩

-

Peter Sloterdijk, Terror from the Air (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2009). ↩

-

David Pearce, “Cost-Benefit Analysis and Environmental Policy,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy, vol. 14, no. 4 (1998): 84–100, link. ↩

-

Under the Trump administration, the EPA has rolled back a number of emissions and air monitoring regulations. For full a list see Harvard Law School Environmental & Energy Law Program’s “Regulatory Rollback Tracker,” link. Under the Bush administration, clean air standards were also subjected to significant rollbacks. See “Bush Rolls Back Clean Air Act,” Greenpeace, April 29, 2004, link. ↩

-

George Charles Halvorson, “Valuing the Air: The Politics of Environmental Governance from the Clean Air Act to Carbon Trading” (Doctoral thesis, Columbia University, 2017), link. ↩

-

Coral Davenport, “Major Climate Report Describes a Strong Risk of Crisis as Early as 2040,” the New York Times, October 7, 2018, link. ↩

-

From a journal entry by Matta-Clark. Quoted in Nicholas De Monchaux, “The Death and Life of Gordon Matta-Clark,” AA Files 74 (2017): 188, link. ↩

-

James Housefield, “Marcel Duchamp’s Art and the Geography of Modern Paris,” Geographical Review, vol. 92, no. 4 (2002): 488, link. ↩

-

Calvin Tompkins, Marcel Duchamp: The Afternoon Interviews (Brooklyn, NY: Badlands Unlimited 2013), 26, link. ↩

-

“Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), Air De Paris,” Christie’s, accessed November 15, 2018, link. ↩

-

Alice Vincent, “Air from a Kanye West Show Selling for $60,000,” the Telegraph, March 6, 2015, link. ↩

-

Irigaray and Marder, Through Vegetal Beings, 24. ↩

-

“The Majority of Seward Park Shareholders Demand the Sale of Our Air Rights,” Petition, link. ↩

Alex Tell is a writer based in New York City. She is currently a graduate student in Columbia GSAPP’s Critical, Curatorial, and Conceptual Practices in Architecture program.