As David Madden of the London School of Economics wrote in June of this year, “housing has been a site of injustice for so long that it is easy to think this condition is permanent.”1 Indeed, while issues related to housing access and quality are endemic, in recent years London has been the site of some particularly scandalous episodes: estates with playgrounds segregated according to ownership or rental status, offices converted into homes of disastrous quality, and the incalculable tragedy of the Grenfell Tower fire among them.2 Considering more day-to-day injustices in addition—rising homelessness figures, decreasing numbers of truly affordable rented properties, developer-led gentrification, insecure tenancies, flimsy tenants’ rights in the private market—it is clear that the overall picture is catastrophic.3

In response, increasingly desperate and frustrated Londoners are turning to previously unorthodox methods to resolve the housing questions that the British government consistently fails to address. In the UK, community-led housing developments have long occupied a marginal position, particularly in major cities.4 While there is a rich history of squatted and other autonomous communities in London, these have been heavily policed in recent years, arguably another contributing factor to high levels of homelessness. The relative prominence of baugruppen projects in Berlin—in which a group forms to collectively develop high-density, multifamily housing—and other cooperatively organized equivalents across Europe has not, to date, been matched in the UK.5 Yet this trend seems to be shifting.

In December 2017, London mayor Sadiq Khan signed a rather obscure document: the Request for Mayoral Decision–MD2207, titled “Homes for Londoners Land Fund.” MD2207 approved the establishment of a £250-million investment fund to buy and prepare land for housing in the city, in accordance with the mayor’s apparent:

commitment to taking a more interventionist approach to London’s land market with the aim of: getting more homes built; increasing the proportion of affordable homes; accelerating the speed of building; and capturing more value uplift for the public benefit.6

Six months later, in May 2018, it was announced that this fund would be put to use for the first time to purchase a plot of land owned by the National Health Service (NHS) at St. Ann’s Hospital in Haringey, North London, in support of a development proposal by local residents. This was an interesting move by Khan’s office, the Greater London Authority (GLA). The sale of (public) NHS land is not in itself unusual; it has become a common tactic to “plug a hole” in the NHS budget as well as to release land for housing. However, as reported by a New Economics Foundation (NEF) report in June 2019, only 5 percent of the homes eventually built on NHS sites are for genuinely affordable rent.7 The GLA’s intervention in Haringey thus signaled a different possibility—that the benefits of public land might stay in public hands. More significantly, this purchase came after years of organizing and campaigning work by citizens close to the hospital site. St. Ann’s has been the focus of local attention since 2015, when the site was earmarked for sale by the hospital in an effort to raise funds to upgrade the mental health services it provides in the area. Dismayed with the prospect of losing public land to private finance, a group of local residents banded together to form the St. Ann’s Redevelopment Trust (StART) in 2014. The trust, which has over three hundred members and is backed by dozens of local businesses and organizations, developed a proposal for eight hundred residential units, a minimum of 65 percent of which would be deemed genuinely affordable relative to local income levels.8

Another six months later, in October 2018, Khan and the GLA awarded nearly £1 million to the Rural Urban Synthesis Society (RUSS) in Lewisham, a neighborhood in Southeast London. This grant allowed the RUSS, a community-led organization with over 850 members, to move forward with the construction of a self-build housing project of thirty-three apartments via the local authority and a community land trust (CLT). A further eight months on, in January 2019, the mayor’s office took another step to support the community-led housing sector with the £38-million London Community Housing Fund, which is expected to facilitate the construction of five hundred residential units by 2023. The online community-led housing resource and advice hub, also partly funded by the GLA, lists over forty projects across the city that are either emerging or recently completed, meaning it’s fair to say community-led housing in London is, in the words of the organizer of another community-led project at Camley Street in Kings Cross, “definitely the zeitgeist.”9

What this moment might mean for the city and its broader housing crisis as a whole is a complex and intriguing prospect. The benefits of this model are ostensibly very clear—housing developed by cooperatives and communities is virtually always affordable in the long term and tends to be protected from market speculation through the creation of community land trusts. They are also often developed to serve the needs of specific demographics that are left out or rarely considered by mainstream house-building programs: the Older Women’s Co-Housing and London Older Lesbian Cohousing groups being two self-explanatory examples.

However, the community-led model also has many (if perhaps less evident) flaws. Behind each unit successfully completed are thousands of voluntary hours, a steep learning curve to grapple with the city’s planning system, and a struggle to secure funding—all significant barriers to participation in the sector. In addition, the number of homes community-led developments are able to deliver falls considerably short of meeting any kind of quantitatively effective housing need. A simple point of comparison: the £38-million London Community Housing fund aims to deliver five hundred units over the next four years, whereas a report by the GLA and a group of housing associations published in June 2019 found that £4.9 billion is needed to support targets of sixty-five thousand new units per year from 2022 to 2032.10

This is not to argue that community-led housing schemes are without value, nor that the colossal effort that goes into their organization, development, and eventual construction should be spent elsewhere. Indeed, it is in reference to those huge forecasted figures from the GLA that community-led developments take on a particular significance: namely, to point to the kinds of housing, or more pointedly, homes, that we should be building. That is, the value of community-led housing in London in 2019 can be seen in the attempts of its initiators to mold the built environment into something with intangible value, something imbued with emotional and embodied life rather than simply units of housing. Three exemplary case studies—St. Ann’s in Haringey, the RUSS in Lewisham, and Camley Street in Kings Cross—offer their own distinct possibilities and perspectives—via health, methods of organization, and food, respectively—for how projects might point to new ways of living in London.

StART: Housing and Health

The historic relationship between architecture and public health has been amply explored, and London’s contribution to this history is well known.11 Beyond the familiar history of architecturally significant health care facilities—from the twelfth-century origins of the still-standing St. Bartholomew’s Hospital through the modernist innovations in light and glass at the Finsbury Health Centre, the “Peckham Experiment,” or, more recently, Maggie’s Centres in the city—housing and health in the city are closely entwined. The clearance of slums at the turn of the twentieth century to make space for early social housing developments, first in Liverpool and later in London, came with a strong argument for public health; more spacious, better constructed homes would prevent the spread of diseases and improve the well-being of the broader public. This causal relationship is still recognized today, most notably in the negative health impacts caused by the aforementioned housing failures affecting London and the UK as a whole. A 2015 report by the Building Research Establishment found that poor housing is costing the NHS an estimated £1.4 billion per year.12 In addition, the housing and homelessness charity Shelter found that 21 percent of adults have suffered from housing-related mental health issues, succinctly pointing out that “housing and mental health in England are both frequently described as in ‘crisis.’”13

This reality is central to the proposals at St. Ann’s. As noted, their proposal is for eight hundred homes, with 65 percent at prices set in relation to local incomes and for 150 homes to be held by a community land trust (CLT). The CLT would retain the properties and the land on which they sit in perpetuity, thereby preventing the possibility of prices rising beyond the realm of the affordable or individual profiteering on the homes. These facts alone have the potential for a radical impact on residents’ health, housing security, and affordability being a major factor in the high levels of poor mental health described by Shelter.

The master plan put forward by StART has been overseen by 6a Architects and Maccreanor Lavington, both London-based offices. Currently the hospital is made up of mostly squat, brick buildings, many of which are out of use, spread across 7.1 hectares and enclosed by a tall brick wall. The proposed design by StART and the architects is for a new mixed “neighborhood” made up of apartments, maisonettes, courtyard housing, family houses, communal living dwellings, and a fourteen-story tower.

Crucially, the hospital will remain on the site, and the new homes will be integrated, both physically and socially, within these health care facilities. “We did consultations with the public to see what they want on the site,” explains David King, a spokesperson for StART. “That was distilled down into three main themes. One was community-led, genuinely affordable housing in perpetuity, the other theme was the environment, and the other theme was health.”14 Thus this proposal frames the future homes and adjacent public spaces as sites of care in parallel with the medical history of the site (there has been a hospital on site since 1890, although its connection to health is rumored to date back to the Middle Ages). For example, the new proposal involves ample green space for therapeutic gardens, allotments and exercise, as well as sheltered housing for people dealing with mental health crises, or an arm’s length solution for elderly people preparing to move into full-time care. Of course, the success of this integrated health care and housing cannot be guaranteed by architectural or urban design alone. The very fact of the sale of the NHS land is indicative of the broader struggles of the health service, which continues to deal with underfunding, and thus, paradoxically, the success of any development following the StART model would be in large part dependent on well-resourced public health facilities. Nonetheless, health and the home are inseparable, and at StART this priority is manifest in every aspect of the project.

RUSS: Self-Build and Self-Organize

At the other end of London, another community-led project is picking up on its local history. The Rural Urban Synthesis Society (RUSS) in Lewisham finds its roots in the self-build projects of Walter Segal, the German-born guru of self-build whose projects from the 1980s remain in the area to this day. The RUSS was initiated by Kareem Dayes, the son of two of Lewisham’s original self-builders, and the project received planning permission for their Church Grove pilot project of thirty-three homes in June 2018, as well as a grant of almost £1 million ($1.3 million) from the GLA in October 2018. The bulk of construction of the homes on site is due to begin in October 2019.

Self-build, and specifically the Segal construction method, seemed to some to hold the potential to revolutionize housing in the eighties, although the phenomenon never took off. The homes that were built in Lewisham remain as something of an oddity, an “anarchist housing estate” that attracts architecture students to open days, keen to see the South London houses on stilts.15 The method retains its appeal in the contemporary city, however, as a way to reduce construction costs by between 10 and 15 percent according to Ted Stevens, a RUSS trustee and former head of the National Custom and Self Build Association. At Church Grove contractors are being hired to build waterproof shells, before members of the RUSS—having been trained on site—will clad the shell and fit out the interiors of the homes, communal areas, and landscaping, following a design by Architype.

Yet, in a sense, the esoteric, non-universal nature is also one of its strengths. Self-build is supported by the RUSS as a way of producing a higher quality of homes that can cater to specific needs. Research by Cambridge University in 2014 found that British homes were the smallest in Europe, while the housebuilding industry is dominated by ten large companies in the private sector providing a limited range of products.16 For the RUSS, self-build has the potential to bring a higher quality of space and a greater range of living arrangements reflecting the diversity of domestic groupings in the twenty-first century (that said, the Church Grove project is fairly orthodox in its offering of individual family apartments as opposed to, say, multifamily groupings as might be found in a cohousing situation). As Stevens acknowledges, the pilot project at Church Grove has necessarily involved a steep learning curve for all involved. But this indicates that future projects by the RUSS will likely be better organized, meaning these bespoke homes with high-quality spatial standards may be available for a range of future residents beyond just those who can build for themselves.

Camley Street: Food on the Table

At Kings Cross in the center of London, behind the leviathan regeneration that continues into its nineteenth year with a recently opened shopping center by Thomas Heatherwick, a peculiar corner of London is hidden on Camley Street. Here, a dead-end road runs between the Regent’s Canal and the Kings Cross railway lines and separates a small housing estate from a light industrial estate. Behind the shuttered doors and PVC curtains of the industrial estate are businesses with names such as Daily Fish, The London Fine Meat Company, Knight Meats, Taylor Foods, Southbank Fresh Fish, Direct Seafoods Scotland, Hensons Famous Salt Beef, and Alara, a muesli producer founded by its maverick founder Alex Smith who, as the story goes, began the business with £2 he found on the floor in 1975. The schools, offices, restaurants, prisons, and hospitals of the city receive their food from here every day; put simply, London is fed by Camley Street.

And yet, the estate is under threat. As with NHS land across the city, local authorities have long been selling off their assets to fund basic services. In the case of Camley Street, it is the London Borough of Camden that has been under pressure to sell to private hands in order to finance council services elsewhere. In response, a neighborhood forum was designated in 2013 to come up with an alternative Neighborhood Development Plan, incorporating the views of businesses and local residents. “We got really significant feedback,” explains Christian Spencer-Davies, the managing director of architectural model-makers A Models, a spokesman for the Camley Street Neighborhood Forum, and a recognizable figure in London’s architectural community thanks to his penchant for the color orange. “We’ve only got one lady who doesn’t like articulated lorries, and apart from that, there’s no negative talk about the industrial site. There’s a lot of sympathy for that fact that there are five hundred real people who work there.”17 While developers often begin from abstract and generic notions of what their clientele might want—and what sorts of spaces or employment they might prefer not to have nearby—the design and engagement processes that community-led housing entail show a more nuanced understanding of local context and how this might influence a future development.

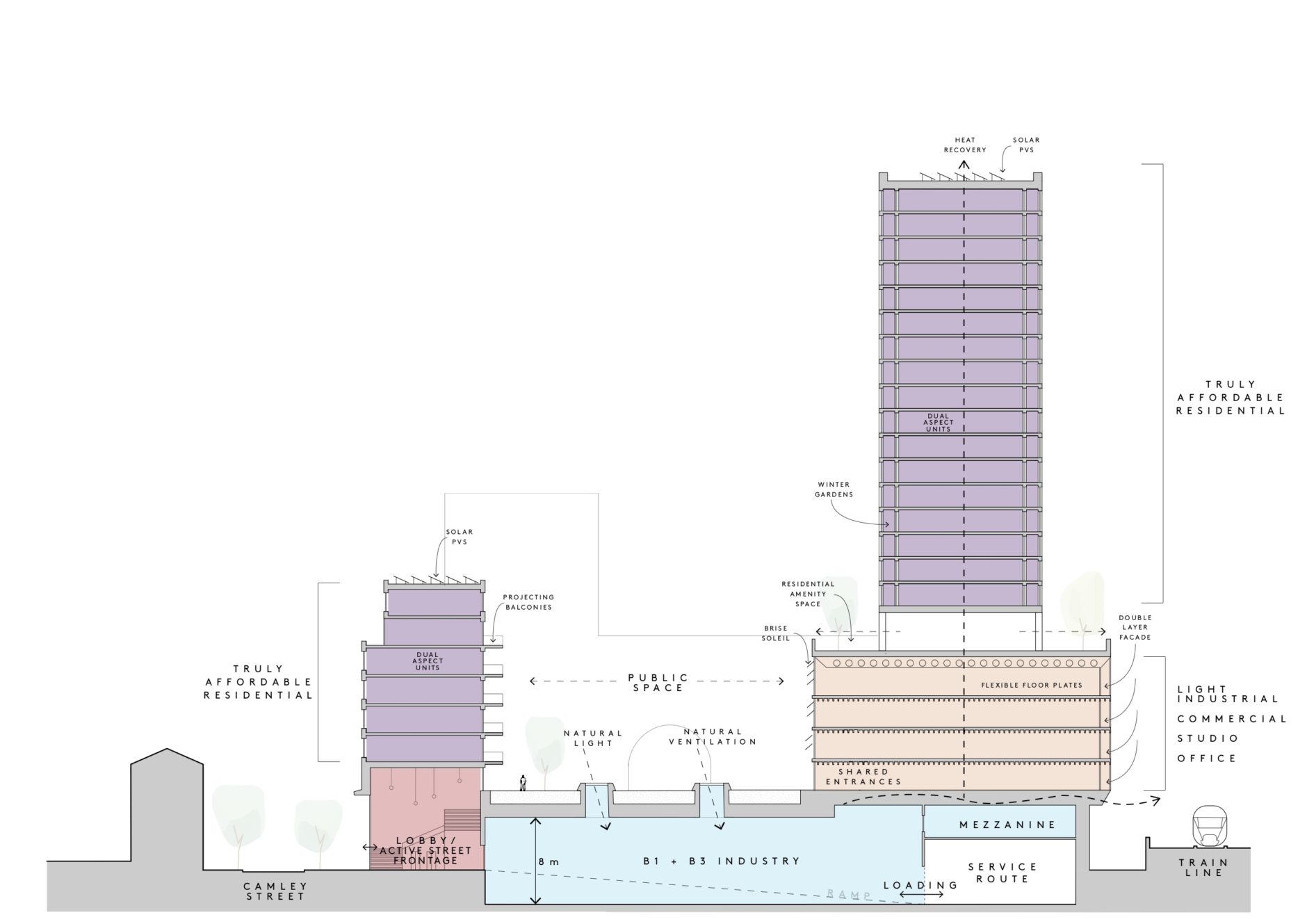

The neighborhood forum’s proposal for the site, created in collaboration with London-based social housing specialist Karakusevic Carson Architects, is for a new form of mixed community that combines industrial with residential uses. The masterplan imagines a site organized via vertical strata as opposed to more orthodox zoning in which the city’s functions are separated along a horizontal plane. The development would aim to provide over seven hundred “genuinely affordable” dwellings with facilities such as gardens, communal kitchens, and laundries. The proposal is for an undoubtedly very tall development, something made possible by the high-rise, high-end housing erected at the Kings Cross regeneration site down the road. In addition to the housing, it would double the workspace on the site, in theory doubling the amount of jobs potentially available, while maintaining the area’s focus on food production. The proposal aims to integrate industrial and residential uses for both functional and social reasons, with imagined innovations such as heat retained from industrial usage to warm the homes on site and planning industrial logistics—deliveries, large lorries, etc.—with domestic patterns in mind.

Still in the early stages of planning, the development has faced some criticism from Camden council around claims that the businesses behind the neighborhood proposal have prioritized their own needs over others beyond the immediate industrial estate and street.18 While the specifics of this claim are disputed by the neighborhood forum, it does raise a broader critique of community-led proposals: Who is and is not part of the decision-making processes? Who makes up the “community” behind such a development?

Imagining a Better Housed City

Just as StART’s proposal seeks to think about health and the built environment holistically, or the RUSS thinks about auto-construction as part of the life cycle of an empowered community, at Camley Street the role of food production and other small industrial functions are tied into quotidian reality of what it means to live in London.

Beyond the potential for these projects to provide housing at a price accessible for normal Londoners in a city with desperate need, one of the most interesting outcomes of discussions during these projects is how the idea of home might take on new meanings should these developments come to full fruition—which is by no means a guaranteed outcome. At the heart of each of these projects is an intention to create places where the home is not an abstract, commodified, or even disembodied unit bought offshore and off-plan but a complex, socialized, physical space where bodies can be cared for, can consume healthily, and can coexist closely. The development of these projects through the early stages of local organization and into the labyrinthine depths of the British planning system (beginning nearly ten years ago, in the case of the RUSS) via hours upon hours of voluntary work on evenings and weekends is testament to the fact that new forms of living and organizing contemporary living are needed.

Indeed, the annual report into domestic trends worldwide by Ikea, of all places, published in October 2018, found a sharp increase in the number of people feeling uncomfortable in their own homes: one in three people all over the world say there are places where they feel more at home than the space they live in. This is a striking statistic, somehow more striking coming from the company that furnishes our home-non-homes. This can be explained in part by changing work habits: more people are living in cities and more people are freelancing or working longer hours, blurring the once rigid domestic–work-space binary. On the other hand, economic conditions in these cities and broken housing markets are creating a lack of comfort, belonging, ownership, privacy, and security in the home, according to the Ikea study.19 In contrast, the community-led projects explored here are centered around agency and security of tenure in mixed developments that cater to the varying sizes and needs of the modern domestic social unit, in all its divergent forms.

It is important to note that community-led housing developments in their current form cannot and will not be the only solution to London’s housing crisis. As argued by Owen Hatherley in the New Socialist in 2018, these developments might form part of a broader smorgasbord of housing options including cooperative and communal housing, “provided that there is abundant provision for those that do not have the time or inclination to personally manage their housing.”20 It thus remains imperative that the city’s local authorities retake the lead in providing good-quality council housing for all on the massive scale required. To turn to Hatherley again, this model “has virtues in terms of security, de-commodification, and of stopping people from having to worry about their housing that no other model has yet matched.”21 This, in turn, must be facilitated by a national government committed to meeting the basic needs of its citizens, something successive Conservative governments have wholeheartedly failed to do.

It is also important to emphasize the voluntary hours that have gone into these projects. Sadiq Khan’s decision to support RUSS or StART, and the ongoing development of the Camley Street proposal, come on the heels of extraordinary levels of voluntary commitment on evenings and weekends from individuals who seek to improve the lot of their neighbors across different streets and boroughs. As Spencer-Davies puts it, “You’ve got to have a really good reason to do this. In our case it’s because we’re threatened; therefore we’re prepared to make quite an effort … but without that threat, you’d lose the will to live quite easily.”22 Ted Stevens from the RUSS makes a similar point:

As briefly discussed in relation to the Camley Street project and the self-selecting nature of the businesses involved in the neighborhood plan, there are potential issues across each of these projects worth addressing in this regard. The community-led nature of the projects inevitably raises questions around who constitutes the “community” and, more pressingly, who does not. In addition, the pursuit of generic housing rather than the pursuit of specific options for those already marginalized or disadvantaged in mainstream domestic options— people of color, undocumented migrants, people with disabilities, or those at higher risk of homelessness, such as trans individuals—may prove problematic. However, the collaboration with local authorities required by these developments in the provision of housing means the communities they establish are unlikely to fall within the same restriction of self-selection as more autonomous cohousing or cooperative developments.23 At the RUSS, for example, they have adopted an allocations policy based around local connections and affordability criteria that aligns with Lewisham council policies.24

Additionally, the case studies discussed here appear to be having a ripple effect. These projects don’t take place simply so that a select group can have nice, affordable housing in their area (although this is a valid and vital aspect), but they seem to follow a genuine belief that these might change the city for good. In Lewisham, for example, the RUSS has aspirations beyond the pilot project at Church Grove: “We can’t fit our eight hundred members into our first thirty-three homes,” explains Ted Stevens. “So our aim is to speed up the process and make it less painful on future ones.”25 What’s more, the process that these projects have already gone through has changed the possibility for other groups to follow suit in a smoother fashion. The Request for Mayoral Decision–MD2207 and the establishment of the land fund and community-led housing hub can almost certainly be read in response to the high-profile efforts of StART and their conversations with the GLA that go back two years, as well as other groups going back further. Similarly, in the case of Camley Street, Camden Council has not sold the site to a commercial developer, deciding instead to develop it themselves, a decision that may not have been made were it not for the efforts of the Camley Street neighborhood forum. What’s more, in the cases of Camley Street and StART, even if the community-led master plans are not adopted by the GLA or Camden Council, both authorities are guaranteeing much higher levels of orthodox social housing than would have otherwise been offered had the pressure and public scrutiny of these campaigns not existed. That is, the movement of community-led housing developments is already creating the conditions for a better housed city.

There is still a long way to go for each of these projects. The GLA is looking for a developer to work on the site in Haringey, and there is no guarantee they will go ahead with StART’s plan (although there is a guarantee that whatever is built there will be 50 percent “affordable” housing). Similarly, the decision of how development goes ahead at Camley Street lies wholly with the Camden councillors—they may yet go with a development that removes the small businesses in favor of unaffordable homes, desperate as they are for cash. These decisions continue to play out in public meetings, news reports, and letters pages across the city.26 Owing to its smaller scale, the RUSS is further along, although the work to train their self-builders is only just beginning; long gone are Segal’s days where houses were built by amateurs in shorts and T-shirts with kids wandering around on site.

Nonetheless, the momentum is with those who can see a better future for the city, a momentum that is spreading from activists and volunteers to future residents and future builders. As Spencer-Davies sees it, “even successful professionals—bosses of big architectural practices or planning companies or developers—are prepared to spend their time thinking, ‘There must be a better way.’”27

-

David Madden, “The Fight for Fair Housing Is Finally Shifting Power from Landlords to Residents,” the Guardian, July 3, 2019, link. ↩

-

On playgrounds, see Harriet Grant, “Too Poor to Play,” the Guardian, March 25, 2019, link; on office-to-resi developments, see Ella Jessel, “Khan Urged to Help Scrap ‘Deeply Flawed’ Office-to-Resi Policy,” the Architect’s Journal, June 3, 2019, link; on the Grenfell Tower, see Stuart Hodkinson, Safe as Houses (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2019). ↩

-

For more on housing in contemporary London, see Anna Minton, Big Capital (London: Penguin, 2017); John Boughton, Municipal Dreams (London: Verso, 2019); John Ryan-Collins, Toby Lloyd, and Laurie Macfarlane, Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing (London: Zed Books, 2017). ↩

-

This essay adopts Zohra Chiheb’s understanding of community-led housing as being developments derived from meaningful community engagement; developments owned and/or managed by the community; and developments whose local benefits are clearly defined and legally protected in perpetuity. ↩

-

The reasons behind this would be worth further investigation—my suspicion is a paradoxical combination of the once far-reaching provision of social housing by the state together with the isolationist curtain-twitching/Englishman’s castle cultural strain. ↩

-

Greater London Authority, “MD2207 Homes for Londoners Land Fund,” December 15, 2017, link. ↩

-

Hanna Wheatley, “Still No Homes for Nurses,” New Economics Foundation, June 3, 2019, link. ↩

-

The semantics of “affordable” housing in London deserves its own essay but, put simply, housing defined as “affordable” in the UK is subject to a rent control requiring rent of no more than 80 percent of market rate, making it, in other words, unaffordable. ↩

-

Community Led Housing, London, “Community Led Housing Projects in London,” link. ↩

-

Mayor of London, “Landmark Report Shows £4.9bn a Year Needed to Deliver Affordable Homes,” news release, June 29, 2019, link. ↩

-

See Iain Sinclair, Living with Buildings (London: Wellcome Collection, 2018); Giovanna Borasi and Mirko Zardini, eds., Imperfect Health (Montreal: CCA, 2012); Charles Jencks, Can Architecture Affect Your Health? (Arnhem: Artez Press, 2012); Sarah Schrank and Didem Eciki, eds., Healing Spaces, Modern Architecture, and the Body (London: Routledge, 2016). ↩

-

Building Research Establishment, “The Cost of Poor Housing to the NHS,” briefing paper, BRE, March 23, 2015, link. ↩

-

Shelter, “The Impact of Housing Problems on Mental Health,” April 2017, link. ↩

-

David King, personal conversation with the author, October 12, 2018. ↩

-

Architecture Foundation, “Walter’s Way, Lewisham,” YouTube, August 11, 2015, link.

As with StART, the RUSS proposal for affordable housing also reframes how the home might be conceived of in the contemporary city. The act of physically constructing one’s own dwelling as part of a collective effort is imbued with an agency and control that stands in stark contrast to the alienating and disempowering norms of London’s mainstream housing market. Stevens points out that involvement in a self-build project doesn’t necessarily exclude those who don’t know their way around a building site. “Most houses that are individually built by self-builders aren’t actually built by self-builders. They are organized by self-builders and a builder builds it for them! It’s a bit of a misnomer really.”[^16] That said, self-build and the direct and regular involvement it requires comes with an intense investment of time and labor—meaning the model isn’t universally applicable, emphasizing the individual and excluding those who don’t have the time or ability to attend meetings, construction training, and so on. ↩ -

Malcolm Morgan and Heather Cruickshank, “Quantifying the Extent of Space Shortages: English Dwellings,” Building Research & Information 42 (2014): 710–724; see also link. ↩

-

Christian Spencer-Davies, personal conversation with the author, October 11, 2018. ↩

-

Councillor Danny Beales, “Letters: Facts about the Council’s Approach on Camley Street,” Camden New Journal, July 19, 2019, link. ↩

-

Owen Hatherley, “What Should a Twenty-First Century Socialist Housing Policy Look Like?” New Socialist, September 10, 2018, (link: https://newsocialist.org.uk/a-socialist-housing-policy](https://newsocialist.org.uk/a-socialist-housing-policy text: link). ↩

-

Hatherley, “What Should a Twenty-First Century Socialist Housing Policy Look Like?” Italics in the original, (link: https://newsocialist.org.uk/a-socialist-housing-policy](https://newsocialist.org.uk/a-socialist-housing-policy text: link). ↩

-

Christian Spencer-Davies, personal conversation with the author, October 11, 2018.

Fatigue sets in with some people when they’re involved with a project like this. It seems to take forever, there’s an awful lot of going around in circles. Lots of frustration. Quite a lot of groups never get a project off the ground; they give up and walk away rather despondently.[^24]

-

Francesco Chiodelli, “What Is Really Different Between Cohousing and Gated Communities?” European Planning Studies, vol. 23, no. 12 (December 2015): 2,566–2,581. ↩

-

Rural Urban Synthesis Society, An Innovative Approach to Community-Led Housing, link; for more on housing injustice in the UK, see Brian Lund, Understanding Housing Policy, (Bristol, UK: Bristol University Press, 2017); Dan Bulley, Jenny Edkins, and Nadine El-Enany, After Grenfell: Violence, Resistance, and Response (London: Pluto Press, 2019). ↩

-

Rural Urban Synthesis Society, An Innovative Approach to Community-Led Housing. ↩

-

Peter McGinty, “Letters: Let’s Have Transparency on Camley Street Future,” Camden New Journal, August 1, 2019, link; Beales, “Letters: Facts about the Council’s Approach on Camley Street”; Ella Jessel, “Khan Accused of ‘Watering Down’ Community-Led Housing Project,” the Architect’s Journal, July 23, 2019, link. ↩

-

Christian Spencer-Davies, personal conversation with the author, July 16, 2019. ↩

George Kafka is a writer, editor, and curator based in London. His writing has appeared in the Architectural Review, Frieze, Metropolis, and others. He is a founding member of the &beyond editorial collective and assistant curator of the Oslo Architecture Triennale 2019.