We often say that buildings behave and perform. Can they also mis-perform or misbehave? If this architecture—always in excess of its maker—has agency, it must also have liability and could be tried (and sometimes punished—even exiled or executed).

—Ines Weizman, “Manifesto for the Rights of Architecture”1

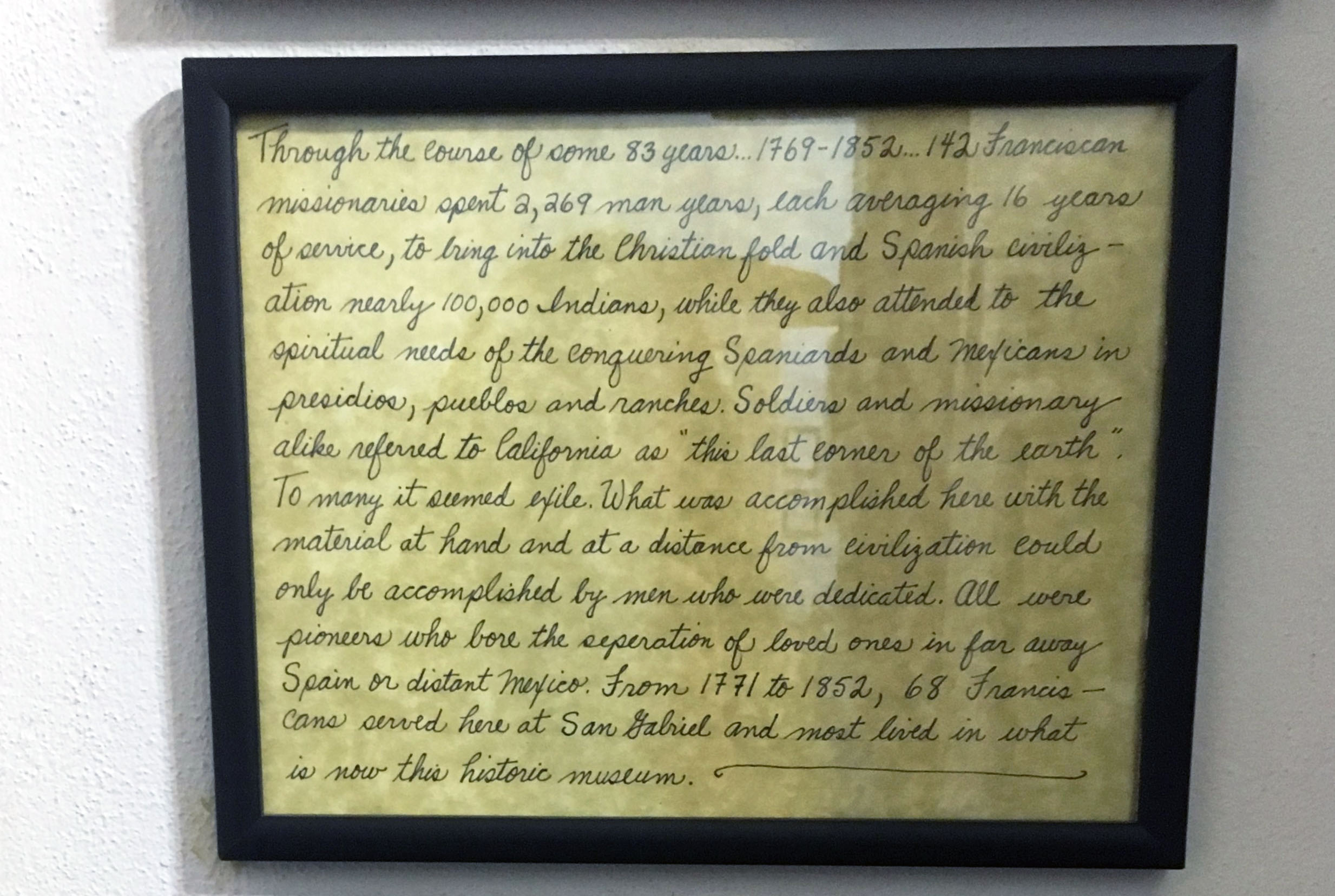

At California’s San Gabriel Mission, there are framed signs placed at child’s eye level. Carefully written in cursive, one sign reads: “through the course of some 83 years…1769–1852…142 Franciscan missionaries spent 2,269 man years, each averaging 16 years of service, to bring into the Christian fold and Spanish civilization nearly 100,000 Indians.” Today the missions are the most visited historical sites in the state. California public and private schools assign pedagogical units on the missions in fourth grade; students visit mission museums and produce models, reports, and drawings based on their research. The mission project, however, has been charged with cultivating a largely distorted history—one that privileges Spanish and Anglo-American colonizers. In short, the California missions have become emblematic of a rewritten settler colonial narrative that is integral to the construction of the identity of the state.

A Very Abbreviated History

In 1769, Spanish Franciscan missionaries, aided by small armies, established the first of a network of twenty-one missions spanning the length of Alta California, the region now known as coastal California.2 Determined to bring Catholic ideologies to the indigenous peoples of the region, the Franciscans were forceful in their efforts. They established military forts, called presidios, and encampments, called reducciones.3 Reducciones were deployed by Spanish colonizers to dismantle tribal and kinship ties within the many indigenous communities living in the region. They established strict codes enforced by physical punishment against violators unwilling to convert to Christianity and to live within the confines of the mission. Indigenous people were instructed in Spanish trades and forced to work as builders, agricultural laborers, and domestic workers.4

By the end of the Mexican–American War in 1848, the promises of westward expansion and the ideology of Manifest Destiny brought Anglo-Americans to California. The agricultural systems and quasi-religious networks established by the Franciscans were appropriated by these newcomers as missions became central to the growing cities that would encroach upon the surrounding landscape.5 As the need for cheap labor in agricultural and service industries increased, Anglo-Americans looked to the missions’ exploitative labor model. Indigenous people, along with Mexicans of indigenous descent, were again subject to control and abuse despite their new citizenship status. Historian William Deverell writes:

Subordinated under yet another colonizing force, native communities were simultaneously charged with being enemies of the state and forced into labor. Through enforced resettlement acts and laws like the 1850 “Act for the Government and Protection of the Indians,” California effectively endorsed a legal slave market.6 More vexingly, George Skelton notes in the Los Angeles Times that “In his 1851 State of the State message to the Legislature, Gov. John McDougall declared a ‘war of extermination’ against California Indians. In 1769, there were 300,000 here. By 1900, their numbers had fallen to only 17,000.”7 The result was that the remaining indigenous populations were sequestered to parts of the state that rendered them visible and captive as subjugated bodies.8

By the middle of the nineteenth century, city planners largely abandoned the foundational Franciscan sites, supplanting them with sprawling urban plans. Los Angeles was developed at the nexus of Missions San Gabriel and San Fernando; the city of San Francisco grew from Mission San Francisco de Assisi; San Diego, Santa Barbara, and San Luis Obispo, all emerged from missions of the same names. To name a mission was to name a city. As for the missions themselves, their heavily plastered adobe walls chipped, their sonorous bells hung silently in their belfries, and their tamed landscapes became entangled with native foliage. In short time, however, their histories and sites would be appropriated, as things tended to be, by Anglo-Americans hoping to reimagine their heritage and legitimize their role in the West.

The Preservation of California Missions

In the early twentieth century, a burgeoning film industry fueled romantic nostalgia for California’s Spanish colonial history, leading to statewide efforts to preserve the missions as heritage sites. Hollywood realized how well the missions worked as sets. Films like Ramona (1910, 1928, and 1936) and The Mask of Zorro (1920, 1940) were set amid the colonial ruins. The overgrown gardens were manicured to sumptuous landscapes, with exotic cacti and burbling fountains; the narratives evoked refined Andalusian courtyards—not utilitarian agricultural fields or the massacres implicit in their production. These reworked projections of the missions renewed their cultural value through what Roland Barthes terms “the filmic,” evoking a mythology and splendor that could be communicated outside of its temporality and place.9 The missions, newly visible and popularized, garnered the attention of preservationists. Though spearheaded by Catholics, mission preservation was now perceived as a matter of national heritage.

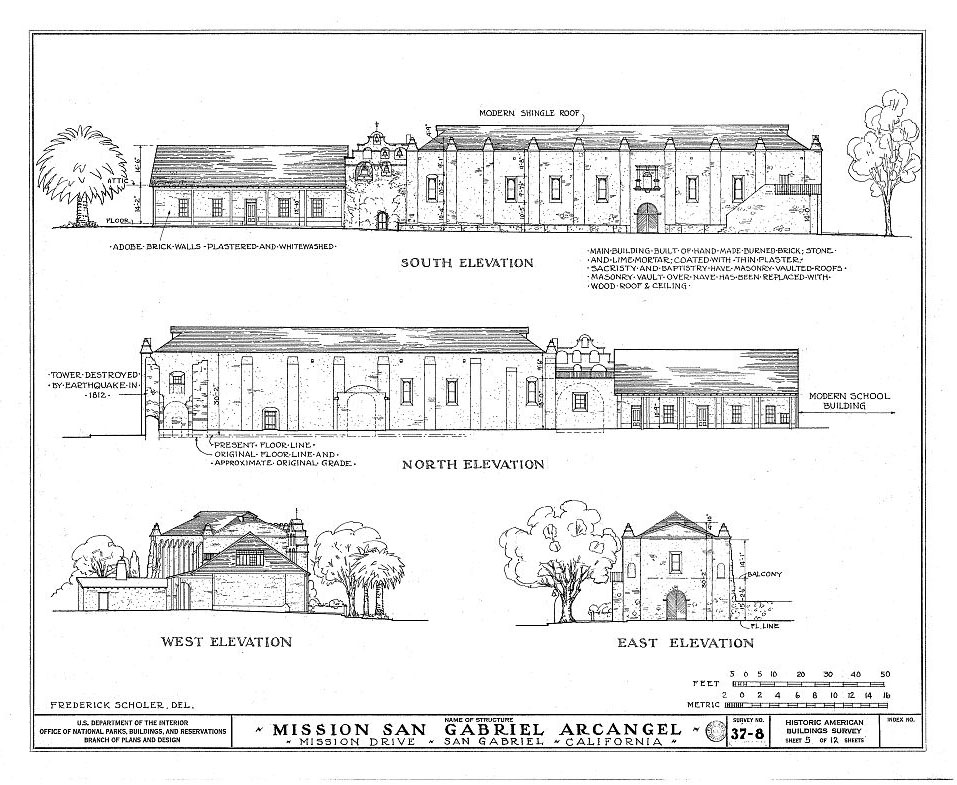

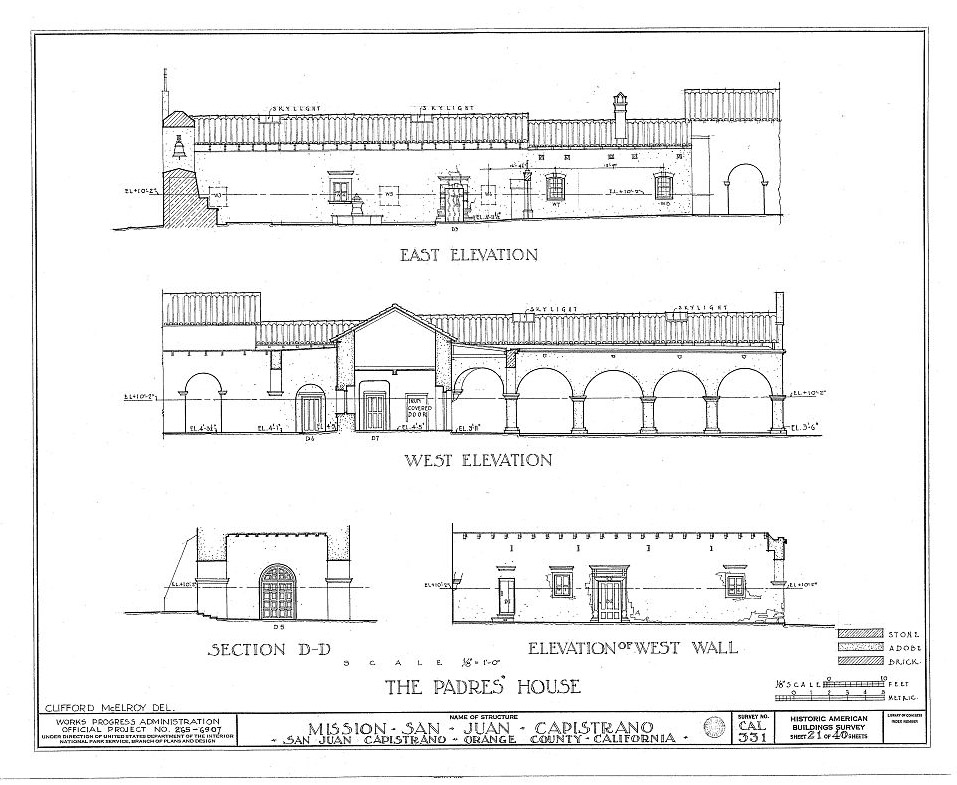

By the 1930s, the US Department of the Interior (DoI) commissioned a Historical American Buildings Survey (HABS) for the missions. In drafting the HABS documents—which included plans, sections, elevations, and selected design details—these preservationists, a group composed largely of documenters from the Index of American Design and architects and surveyors from the DoI, rewrote a particular history of California that glorified its Spanish colonial past. Of a renovation celebration at San Diego de Alcala, the Times-Advocate wrote, “the 162-year-old mission restored to its historic architectural magnificence, was dedicated again to its work for humanity.”10 These initial renovation efforts established a standard against which the future state of the missions would be evaluated. Like other HABS drawings, they captured superficial qualities deemed valuable to the DoI and the Index of American Design.11 These qualities of architecture related the missions to classical works by Vitruvius, Alberti, and other Roman ruins but failed to incorporate the legacies of violence the sites embodied. Through drawings, the DoI established an ideal state of the missions that rejected or ignored indigenous presence. In preserving a mission typology that elided historical labor and atrocities, these documents manifested a new and disturbing architectural legacy.

Scanning the twenty-one-sheet sets, the strategic similarities are striking. Plans are oriented toward central courtyards, framed by arched arcades; the drawings index the range of references the missionaries borrowed from baroque Spanish churches. Bell towers, recorded in elevation, distinguish one mission from another. Monumental ruins are detailed; stucco is elegantly chipped to reveal underlying brick or adobe; ornamentation is strictly deployed along window or door frames. Collectively, these highlighted details invoke what aboriginal journalist Daniel Browning identifies as markers inherent in monumentalism. Browning writes:

Entrenched in the architectural language of Greek and Roman classicism, monumentalism is a form of self-worship. It inflates the national ego, inoculates the mind and anaesthetizes dissent… The evocation of a glorious imperial past invokes a kind of wilful [sic] amnesia that forgets the excesses and violence of the Roman empire.12

These documents evoke European classicism in order to not only promote what the Index of American Design refers to as a “national and ancestral aesthetic” but also to situate the California missions within that lineage.13 There are no references in the documents to the workforce that produced this aesthetic, only to the legacy to which they are indebted.

Top: Antonio Curzado, Roman Catholic Diocese of Los Angeles, et al., “Mission San Gabriel Arcangel,” 428 South Mission Drive, San Gabriel, Los Angeles County, CA, 1933. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/ca0291.

Bottom: Roman Catholic Diocese of Los Angeles and San Diego, et al., “Mission San Juan Capistrano,” Olive Street, between U.S. Highway 101 & Main Street, San Juan Capistrano, Orange County, CA, 1933. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/ca0449.

The documents’ erasure of the indigenous workforce that produced and rebelled against the missions is a historical sleight of hand.14 Details, like the ubiquitous red clay roofs, were drawn in exacting detail without clarifying that they were first used to protect the buildings from arson attacks by tribes resisting the colonization of their lands. Recording the buildings through architectural drawings and drafting laid claim to the missions. Through graphical representation, they were folded into American history and documented for American posterity. Anglo-Americans managed to refute the Spanish colonial past that they had quashed in the Mexican–American War and reclaim it as their own. Americanization, introduced as a civilizing project throughout the country in the early 1900s, aimed, in the West, to reform the indigenous and Mexican populations but failed to integrate them equally into citizenry.15 These populations continued to be socially categorized and otherized. Missions were built, according to the newly minted Anglo-American narrative, by happy, docile “neophytes,” who welcomed the courageous Spanish padres. In continuing what preservationists had already asserted in their documents, this new Western tale was not for everyone; namely, brown lives were still less valuable than white ones.

Modeling the California Missions

Around the 1960s, California’s schools, both public and private, began to adopt the California Mission Model Project that is still practiced today. While initially not mandated by the state, by the 1980s it was common enough in fourth-grade classrooms that the state produced a formal curriculum. The pedagogical unit, a joint project of the Department of Education and local school systems, aimed at teaching ten- and eleven-year-olds state heritage and history but also research practice.16 Though the state no longer mandates the mission project and, in fact, discourages mission modeling as of 2017, there are still a number of private and public schools in the state that continue to focus on the mission modeling project as the state heritage history project. Furthermore, the state has offered no substantial pedagogy to help the teachers develop an alternative curriculum. Students are asked to research when and where the missions were constructed, who founded them, and what tribes lived there—all questions with seemingly definitive and easy answers. The models, made from premade foam-core kits or cheap craft materials like sugar cubes and cardboard, serve as pedagogical tools that reinforce oppressive narratives. As historian Elizabeth Kryder-Reid argues, the models ultimately produce an ideal mission materiality that has “perpetuated an idealized representation of the missions’ past, both visually and rhetorically, that is at best exclusionary and at worst perpetuates claims of racial superiority implicit in settler-colonial narratives”17 Through the promotion of simple modeling materials, educators further simplified and redacted a complex materiality.

In its reductionism, the fourth-grade mission pedagogy presupposes that missions were, at their worst, neutral sites of symbiotic production. The mission models do nothing to disabuse California’s students of these notions. The research that students produce in tandem with the models superficially addresses indigenous labor and housing, but the sugar cubes and hot glue guns rapidly dispel any sense of hand-wrought materiality extant in the missions. Aesthetics are political and can be critically examined, even in the fourth grade. Aesthetics do not hinge on some universal given. They are a part of a cultural model that is learned and invoked and can signify different things in different contexts.18

The mission model can, in fact, be parsed into three models: the epistemological model of learning about the missions; the physical model that students produce to analyze the sites; and the cultural model that is produced as a result. Today the buildings are mostly owned by the California Mission Foundation, an organization that purports to preserve “the landmark California Missions and associated historical and cultural resources for the benefit of the public.”19 In their role as both pedagogical tools and representatives of the state, mission museums are key producers of state identity. However, as nonprofit, tax-exempt, public-benefit foundations, the missions are beholden to the people of California. They receive state aid, which legally confirms their role to “ensure that future generations also have the benefit of experiencing and appreciating these great symbols of the spirit of exploration and discovery in the American West.”20 And, while the state of California and the missions themselves have made recent strides to rectify the troubling language of their narrative, their actions amount to very little when compared to the intergenerational legacies and violences of their preservation.

Missions on Trial

As monuments, missions preserve California’s Spanish colonial past and embody false ideas of racial superiority. Is the verdict then to put them on trial, as Ines Weizman would propose? Or to abandon the Mission Model Project? Or, perhaps, leave the missions to fall into their own ruin in exile? The legacy and aesthetics of the California missions is too entrenched in popular vernacular to be abandoned. Instead, an iconoclasm might be built through critical modeling practices and artistic interventions.

Missions are enshrined within the cultural identity of California. Their aesthetic legacies are embedded in the Taco Bell logo and in the Stanford University campus. Throughout the state and country, the syncretism of California Mission Style has further bastardized itself. The tectonic heft of the mission walls, which often span a thickness of four feet or greater, is superficially mimicked with stucco-sprayed drywall. As with the sugar cube and foam-core models, these abstractions are significant. The heft is the result of hundreds of handmade adobe bricks produced by indigenous laborers forced to work in inhumane conditions. The heavy, indelicate ornaments that frame mission windows and doors were not the work of skilled European craftsmen but of indigenous people producing simulacra of the missionaries’ recollections of Spanish landscapes.21 California mission style is necessarily a de-refinement.

But it is not just their style that is reproduced and preserved. Though the HABS documents end at the property lines established in the 1930s, the missions were connected rhizomatically through a massive network of agricultural landscapes. One mission could own hundreds of acres of land and thousands of indigenous people to work the land. The systems enacted in this landscape have continued to spread. Labor and migratory laws continue to devalorize and dehumanize brown bodies. The missions, now reduced to their main quadrangles, draw no parallels or connections from their histories as vast agricultural complexes to the current state landscape. In another carefully written sign at Mission San Gabriel, a fourth grader may learn, “Some Fourth Grade Information ~ The Mission was a large farm where the Native Americans were serfs who cared for… Oranges, Citrons, Limes, Peaches, Pears, Pomegranates...” The author lists over thirty goods produced on the site. More energy is expended on the fruits of the labor than on the labor itself. Meanwhile, Mission Indians are treated as bygone relics, serfs who were there until they were not. Author Deborah Miranda describes an incident in her memoir, where, upon introducing herself as a Mission Indian descendant, a fourth-grade girl freezes in shock. Miranda speculates that it must have felt “like turning the corner to find the (dead) person you were talking about suddenly in your face, talking back.”22 The missions monumentalize ideas of the past through a kindly padre and his anonymous, docile brown workforce, but this settler-colonial mentality continues through the rhetoric and treatment of Central American workforces and of living indigenous populations.

Unlike other monuments, missions cannot be scurried away to museum storage spaces, where embarrassing colonial histories can be maintained out of sight. And ironically, the few that do attack the pedagogy inherent in mission preservation aim at not the building itself but the statues around it—as in the recent case of several statues of Father Junipero Serra, apocryphal founder of California’s missions, which have been decapitated and splashed with red paint.23 The vandals (artists? critics?) who perpetrated these acts repeatedly let the architecture be. Jorge Otero-Pailos argues that, “Architecture is saved from obsolescence and appears contemporary as it is framed and reframed by preservation as culturally significant.”24 As the statues are newer entries, they are not viewed as part of what is culturally significant—even a vandal will make that distinction.

A successful iconoclasm of the missions fundamentally requires a reckoning of the building and also the program it houses. If we are to examine and argue about their cultural significance, their “work for humanity,” then it is not enough to execute the missions—history has shown us that this only serves to martyrize buildings.25 It is also not enough to exile the missions—ruin seems to only make them more romantic. Instead new kinships and connections should be produced in order to examine the missions. For example, existing social and local networks, like the Catholic Church, the Mission Preservation Foundation, and elected community officials, should embrace reappropriations of the missions and the modeling project in new dialogue with the constituencies they serve. Furthermore, the cultural model of knowledge should embrace and encourage practices that seek to restructure ideas of indigeneity. Indigenous, in this new framework, exists as what David Garneau describes as a “shared self and collective consciousness.” He continues, describing that as a result of meeting with Aboriginal curators and artists “… we discovered shared identities formed within, against, and despite colonization.”26 In other words, the emerging practices of indigeneity are producing new kinships through their complex and evolving relationships to colonization—practices like those of Native activist and author Cherríe Moraga, performance artist Rafa Esparza, and sculptural artist Beatriz Cortez. Moraga’s experimental plays, books, and poems reclaim and reappropriate historical narratives; Esparza’s grueling adobe brick performances materialize the many identities he embodies; Cortez’s works explore migratory realities through fantastical space pods. These are but several artists and scholars, from different fields, backgrounds, and ancestries who are producing a new form of indigeneity in California. A trial, with all of the historical biases and baggage implied, would never be able to produce the iconoclasm possible with these kinships.

Colonialist modernity has only improved the technology through which it wields its power. For too long architecture and design has been allowed to complacently affirm this language. It, too, should look to the expanded futurisms and kinships of marginalized voices, where it can materialize a future that is not fated to repeat the mistakes of the past. Instead of preserving the constructed mission histories and superficially addressing issues through public apologies, missions should invite criticism and revisionism. Their programs should be reconfigured to help elevate the communities they have alienated. The drawings, models, and rhetoric that dehumanized these spaces should now be re-examined by critics, artists, and students in order to find and produce proper modes of representation. The state’s pedagogy should address the contemporary conditions the missions produce instead of historicizing and abstracting negative conditions.27 The missions continue to be central sites in California, so they must participate as truly public spaces and cultural centers, not static, crystallized museums. Their walls should not be treated and reproduced as boundaries of exclusion, guarding an unknown value. Rather, they should be permeable membranes, in flux and in relation to people. Students and artists alike should be empowered to engage with the buildings, find their faults, find their beauty, and determine for themselves what justice looks like. In order to move forward, the buildings must be held accountable.

-

Ines Weizman, “Manifesto for the Rights of Architecture,” in Double, Storefront for Art and Architecture Manifesto Series 2, ed. Serkan Özkayan (Baden: Lars Müller Publishers, 2013). ↩

-

The purpose of this essay is to question the pedagogical agenda of California’s Missions, which requires a critical reading of the placards of information provided in their contemporary exhibitions. Dates were researched for veracity, but I could find no reliable alternatives to this set of dates. As a blogger at the Library of Congress Digital Archives wrote, “It is little wonder that there are no known book-length first-person narratives by California Native Americans for this period: none of these indigenous groups had a written language before the introduction of European culture, and many of the clans and family groups were wiped out so quickly that there was no chance for a record to be made of their experience.” Author Unknown, “California as I Saw It: First-Person Narratives of California’s Early Years, 1849–1900,” Library of Congress, Digital Collections, link. ↩

-

Reducciones, noun (Spanish) Trans: reductions, Syn: concentrations. ↩

-

Francis Guest O. F. M., “Mission Colonization and Political Control in Spanish California,” San Diego Historical Society Quarterly, vol. 24, no. 1 (Winter 1978), link. ↩

-

For example, William Deverell describes San Gabriel Mission as being “as much a regional central place in this era as the plaza in Los Angeles.” See William Deverell, Whitewashed Adobe: The Rise of Los Angeles and the Remaking of Its Mexican Past (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 21.

Despite de jure citizenship status, Mexicans could not exercise the franchise with anything close to the same ease as lighter-skinned Angelenos. On the contrary, the poorest among the Indians and Mexicans of the village might get literally corralled and violently coerced into casting bought votes…[^6]

-

“The name of the law sounds benign, but the effect was malign in the extreme degree. Any white person under this law could declare Indians who were simply strolling about, who were not gainfully employed, to be vagrants, and take that charge before a justice of the peace, and a justice of the peace would then have those Indians seized and sold at public auction. And the person who bought them would have their labor for four months without compensation.” James Rawls, “Act for the Government and Protection of Indians,” part of American Experience, PBS, link. ↩

-

George Skelton, “Don’t Be Too Smug, California: The State Has Its Own Shameful History of Racism and Bigotry,” the Los Angeles Times, August 17, 2017, link. Three hundred thousand is a contested figure; some scholars believe the pre-contact population numbered in the millions. Tragically, the seventeen thousand figure is generally agreed upon. ↩

-

Deverell writes, “Both logic and geography argue that 1850s Sonoratown, north of the plaza, not far from the banks of the Los Angeles River, was in fact in Los Angeles, in California, in the United States…[But] Sonora and Sonoratown were Mexico in the popular perceptions of many an Anglo-Angeleno.” Deverell, Whitewashed Adobe, 16. ↩

-

Barthes, Roland, “The Third Meaning,” A Barthes Reader (New York: Noonday Press, 1982), 330. ↩

-

“Thousands View Mission Pageant,” Times-Advocate, September 14, 1931, link. ↩

-

The Index of American Design was a visual archive that operated under the Works Progress Administration. Their mission was to document American decorative arts from the colonial era to the 1900s. ↩

-

Daniel Browning, “Hiding in Plain Sight: Decolonizing Public Memory,” in Sovereign Words: Indigenous Art, Curation, and Criticism (Norway: Office for Contemporary Art Norway, 2018), 122. ↩

-

“Index of American Design,” National Gallery of Art, link. ↩

-

For a more in-depth look on the explicit production of these documents and settler-colonial narratives that produced them, read: Elizabeth Kryder-Reid, California Mission Landscapes: Race, Memory, and the Politics of Heritage (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016). ↩

-

Deverell, Whitewashed Adobe, 45. ↩

-

Elizabeth Kryder-Reid, “Crafting the Past: Mission Models and the Curation of California Heritage,” Heritage & Society, vol. 8, no.1 (May 2015): 83. ↩

-

Kryder-Reid, “Crafting the Past,” 60. ↩

-

Gloria Anzaldúa writes, “Ethnocentrism is the tyranny of Western aesthetics. An Indian mask in an American museum is transposed into an alien aesthetic system where what is missing is the presence of power invoked through performance ritual. It has become a conquered thing, a dead ‘thing’ separated from nature and, therefore, its power.” See Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: the New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1999), 90. ↩

-

“The California Missions Foundation is a nonprofit public benefit corporation dedicated to preserving the landmark California Missions and associated historical and cultural resources for the benefit of the public through funding preservation activities and facilitating educational programs, conferences, and scholarship.” See “CMF Mission Statement,” California Missions Foundation, link. ↩

-

Wording from Section 2, Act 7 of S.1306, “California Missions Preservation Act” 108th Congress of California (2003–2004). ↩

-

That Spanish landscapes were, themselves, syncretisms of Moorish, Roman, Greek, and other European architectural styles is not lost on preservationists. Signage will often note the birthplaces of padres as they explain the source material for a buttress or colonnade. Regarding the caliber of work, Rexford Newcomb writes, “Some writers say that elliptical arches were used. They were not used deliberately. With poor tools and poor workmen the pure circular curve one expects developed into an approximate ellipse, especially when an arch span was greater than others in a series.” See Rexford Newcomb, “Architecture of the California Missions,” Annual Publication of the Historical Society of Southern California, vol. 9, no. 3 (1914): 233. ↩

-

Deborah A. Miranda, Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir (Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2013), xix. ↩

-

Several statues of Father Junipero Serra, apocryphal founder of California’s missions, have been decapitated and splashed with red paint. From Crux Staff, “Another Statue of St. Junipero Serra Vandalized in California,” Crux, September 17, 2017, link. ↩

-

Jorge Otero-Pailos, “Supplement to OMA’s Preservation Manifesto,” Preservation Is Overtaking Us (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2016), link. ↩

-

Famous architectural examples include Pruitt-Igoe, Pennsylvania Station in New York, and Prentiss Women’s Hospital, but more broadly, consider the Confederate monuments that would never be heard of were it not for their toppling. ↩

-

David Garneau, “Can I Get a Witness?: Indigenous Art Criticism,” in Sovereign Words: Indigenous Art, Curation, and Criticism, ed. Katya García-Anton (Norway: Office for Contemporary Art Norway: 2018), 26. ↩

-

In 2017 the standard California History-Social Science Content Standards Guide was revised to be more inclusive of indigenous narratives, but it continues to compartmentalize the histories. Furthermore, the assignment still requires visiting the missions, where labels and wall text express very little criticality and support a colonialist production of history. ↩

Tizziana Baldenebro is a Ford curatorial fellow at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit. She recently completed a master’s of architecture from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and received a bachelor of arts degree in anthropology from the University of Chicago. Her practice emphasizes critical research and documentation, privileging historically undervalued and underrepresented artists and designers.