The conversation has changed.1

These are extraordinary times for housing policy in the United States. Proposals that just a year ago would have been shrugged off as politically impossible in light of a dominant small-government, pro-market approach have been passed at state and municipal levels. Oregon legislated statewide rent regulation in February of this year, New York State expanded the option to all municipalities in June, and California, a notoriously resistant, if nominally progressive state, followed with a rule in September.2 In late 2018, Minneapolis abolished single-family zoning, seen by many experts to be a key factor in the country’s persistent geographic segregation by income and race since multi-family housing is more likely to include lower-priced apartments affordable to lower-income, predominantly non-white households.3

Elsewhere, city agencies are targeting other long-established cultural standards inscribed in housing. This includes loosening the definition of a legal “dwelling unit,” generally codified as one to be occupied by a single biologically related family and containing a series of standard features, among them a bathroom and a kitchen. Only six years ago, in the search for strategies to increase the production of housing, New York City was focused on reducing the minimum legal dimensions of that unit but stuck to the basic premise that it would serve a single household.4 But late last year it launched a request for proposals to test the option of shared housing—that is, a sort of WeLive in which residents share certain amenities, including kitchens or living rooms—for low-income households.5 Ambiguously perched somewhere between the sharing economy’s deregulation-as-usual and the urgent, experimental reform of a long-broken system, these changes at the level of the individual units themselves nonetheless demonstrate the depth of acceptance that something has to give when it comes not only to housing policy but to housing design in the United States today.

The recently passed policies at state and local levels were made politically possible by, among other things, the extraordinary rise in real estate prices across the country in the last seven years.6 Even some of the companies behind booming, tech-driven cities—San Francisco, Seattle, and Boston among them—are having difficulty finding places for their workers to live, despite their employees’ far-above-average incomes being among the drivers of those areas’ ever-rising rents.7 Just ten years after a recession caused largely by subprime mortgages, today, amid a generally humming economy, the conversation on the “housing crisis” is no longer about saving large-scale financial institutions and is (finally) focused on questions of affordability and fairness as they relate to individuals.

More than 30 percent of US households—almost forty million, of all income levels—now spend more than a 30 percent of their gross income on housing, the typical threshold of affordability; nowhere in the country can a minimum-wage earner afford an average priced two-bedroom apartment at market rent.8 With respect to fairness, the conversation has increasingly focused on the country’s enormous racial wealth gap. The wealth of the median black household is just one-tenth of that of the median white family.9 And while perhaps not yet central in their televised debates, housing has quickly moved to the top ranks under the “Issues” tabs on the campaign websites of the many Democratic presidential hopefuls.

But the federal government, which these candidates are aiming to lead, has always had a difficult role in guiding the nation’s housing policy. Land use and building regulations as well as the one form of taxation intrinsically connected to housing—property taxes—are traditionally the domain of local government. Federal reach into housing has therefore generally been legal or financial: restricted to setting fair housing rules to prevent discrimination and to providing financing to facilitate development, both of which can largely be deployed exclusively as sticks and carrots.10 With the notable exception of public housing, actively built by way of locally established housing authorities between 1937 and 1973, then increasingly scaled back, the federal government has rarely acted directly, through outright capital outlays, in the production of housing.11 Today, any financial support for housing at the federal level largely happens indirectly through incentives to the private market. This takes the form of tax deductions to individual homeowners (mortgage interest deduction or MID), tax credits to corporations putting money toward low-income housing (low-income housing tax credit or LIHTC), and rental subsidies to individual tenants (“Section 8”), among others. In contrast to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), which administers the tax programs, since its founding in 1965, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has never been a strong player, and the Trump administration is further withdrawing the department from its missions of enforcement and funding.12

The absence of a strong federal housing policy sometimes makes it feel as though the country has moved back into the late nineteenth century, when philanthropy and voluntary action was the preferred approach to improving that era’s own housing crisis—defined then as unsanitary and overcrowded “slums.”13 Consider the case of Amazon’s $8 million “gift” to homeless services in its two headquarter cities, Seattle and Arlington, Virginia. The making of these gifts, undertaken by many of Amazon’s peers as well, came largely in response to these companies’ earlier and successful opposition to a proposed tax on businesses in Seattle, which would have generated an estimated $48 million annually for housing.14 In short, housing policy at all levels of government seems to be moving forward and backward at the same time, and all at extraordinary speed.

In architecture too, long-held assumptions with regard to housing are shifting, if more slowly. It’s no longer houses in suburbs that signify wealth and high-rises in cities that embody poverty—quite the contrary.15 The term “public housing” to a person in their late twenties, today, no longer necessarily evokes “towers” or “projects,” but, as a student of mine put it a short while ago, “small-scale, mid-rise, traditionally designed buildings” for which one “needs to have a job” to gain access. This is striking since public housing is perhaps the last, if declining, building stock solidly and permanently dedicated to housing “the poorest Americans,” as scholar Larry Vale has put it, whether or not they have a job or income; in most places, this means primarily elderly and disabled residents.16 But the student’s impression is nevertheless worth noting. Might the stigma of public housing, so often communicated by the dramatic architectural imagery of high-rises like Chicago’s Cabrini Green, be a thing of the past? Might that part of New Deal federal housing policy (the other being the massive support of individual homeownership in the suburbs) be poised for rediscovery just as the Green New Deal is making the rounds? Might this also be the moment when architects question some of their long-held assumptions about how certain architectural strategies—including shrinking, prefabricating, leaving unfinished, and prototyping—do or do not have any impact on affordability and fairness?

Today, too, candidates are connecting affordability and fairness in housing to other policy goals. For New Jersey senator Cory Booker, “Cory’s Plan to Provide Safe, Affordable Housing for All Americans” sees expanded federal investment not only as a way to build more low-income housing but as a way to tack on funding to address the “chronic underinvestment in our nation’s transportation infrastructure.”17 For South Bend mayor Pete Buttigieg, “The 21st Century Community Homestead Act” is not only a homeownership plan but an economic development tool, “creating a multiplier effect of jobs and prosperity for local residents” in towns long suffering from abandonment—that is, not the speculative hot spots of Miami or Los Angeles but the many places between, affected by the opposite of rising real estate values.18 Minnesota senator Amy Klobuchar’s focus on “Bridging the Rural-Urban Divide” is likely motivated by similarly political considerations, addressing voters in not only the coastal areas but the deindustrializing swing states of Ohio and Wisconsin.19 And for former HUD secretary Julián Castro, “People First Housing” not only expands the size of all existing federal incentives for low-income housing to meet actual need but is also a means to the end of “aligning with climate goals” as outlined by the Green New Deal.20

But the overarching, if at times not fully articulated, conversation in 2019 is about the right to housing as a basic human need and about acknowledging the reasons this need has not been met. The degree to which the resulting recommendations for action rest on deeper structural shifts is dubious, however. Almost all of the candidates who provided housing plans by mid-September fall back on three assumptions that have undergirded the US approach to housing for decades: the mantra of supply to lower prices, the mantra of homeownership to build wealth, and the mantra of subsidies to the private market to meet whatever need remains.21 In so doing, very often candidates are resorting to rhetorical arguments and a tool kit of the past without acknowledging the often problematic nature of those precedents.

The emphases on millions of new units of affordable housing recall the last concerted federal effort to address affordability and fairness in housing, half a century ago. In 1968, in an attempt to do something about that era’s “urban crisis,” President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law both the Housing and Urban Development Act, a set of financing programs to promote housing, and the Fair Housing Act, a civil rights law barring discrimination in housing. This legislation was made possible politically only by the urgency of civil unrest, commonly referred to as “riots” at the time, which made tangible to white suburban Americans—a more empowered political bloc—the deep frustration of inner-city African Americans. Motivating the 1968 Housing Act were the recommendations made by the Kerner Commission, charged by Johnson in 1967 to find the reasons and remedies for the civil unrest. The report listed, after police practices and underemployment, “inadequate housing,” and recommended building “within the next five years six million new and existing units of decent housing” for “low- and moderate-income families”—an enormous number for the time, to be delivered primarily through the private sector but made possible by direct federal financing.22 Five years later, President Richard Nixon effectively put an end to these programs, not so much because they were not producing housing units but because of concerns over corruption and shoddy construction, due largely to the lack of federal oversight. This in turn facilitated the argument that the federal government should stay out of housing production altogether and work instead through indirect incentives to the private sector. I point to the “urban crisis” of half a century ago because many of the socioeconomic issues, as well as the diagnoses as to what to do about them, were strikingly similar to today’s.23

Yes, in many places more housing wouldn’t hurt. But more broadly, there is not too little housing but rather an imbalance in its distribution. There is too much of it in some places, namely those places where there are no jobs and poor public services, and too little of it elsewhere. There are two-person households living in five-bedroom, six-and-a-half bath houses with three-car garages while others double up in technically illegal basements. Sprawl and new subdivisions are still a dominant form of development across the United States, and the shortsightedness of this, especially in light of a growing consensus that addressing affordability and fairness in housing is related to addressing climate change, is striking.

Why not limit our consumption of square footage? Why not tax any individual using in excess of four hundred square feet? Why not stop new housing development altogether and use the billions of dollars to improve—in terms of construction quality, energy efficiency, diversity of types, accessibility—what we have? But that would be a nonstarter politically, an acknowledgement of defeat akin to Jimmy Carter’s call to put on an additional sweater if you were cold during the 1970s oil crisis.24 So once again, candidates and economists are calling for millions of new units and keeping their fingers crossed.25

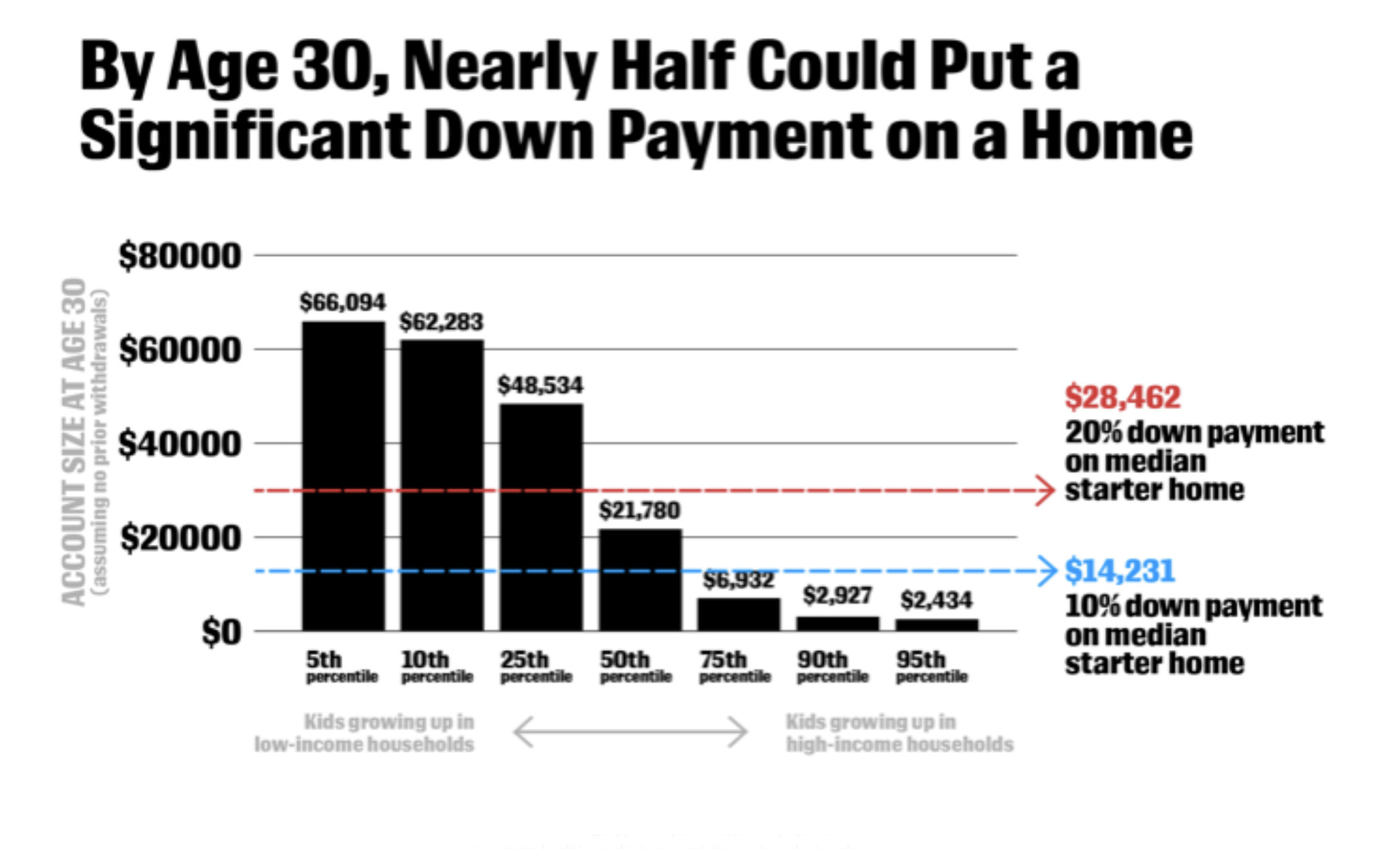

For this reason, Booker introduces his proposal for “A fair shot at homeownership” with a maxim: “In America, wealth means opportunity.” His solution to the problem includes “Baby Bonds,” or a savings account automatically set up for each newborn to accumulate up to $50,000 as “seed money” by the age of 18.26 California senator Kamala Harris is more specifically focused on closing the “racial homeownership gap.” Toward this end, she will provide up to $25,000 in down-payment assistance to qualified first-time homebuyers in formerly redlined areas.27 Warren and Buttigieg, too, position homeownership as a key component of addressing the wealth gap between white and black Americans. In all of this there is a refreshing abstinence from well-worn clichés: “the American Dream,” for instance, is rarely heard. Former entrepreneur Andrew Yang seems to be the only candidate who cites it, only in passing, and with a lower-case “d.”28 Nevertheless, the candidates buy into the promise of homeownership and only peripherally acknowledge the risk and costs associated with it, for instance, by calling for homeowners’ education programs and stronger regulation of lenders.29

Again, where is the awareness of historic precedents? Low-income homeownership programs have repeatedly fallen short. The 1968 Housing and Urban Development Act also included a low-income homeownership program, called Section 235, launched with the same goal of giving access to the purported benefits of homeownership to those previously excluded, and with similar tools—no down payment, very low interest loans. The resulting “predatory inclusion,” as historian Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor puts it, did not play out well.30 Buttigieg’s use of “homesteading” is similarly problematic. It puts his proposal to transfer ownership of unoccupied land in places with declining property values at no upfront cost to qualifying residents in direct lineage with President Lincoln’s 1862 Homestead Act. That legislation was the basis for the brutal displacement of Native Americans to create what was billed as vacant land for settlers, and often resulted in massive resource extraction through speculators, rather than in the idealized, self-sufficient farmsteads it envisioned.31

Why are none of the candidates seriously promoting the various models of collective and non-market-rate-based homeownership that exist, both in the US and abroad? It seems an easy way to hedge bets against the need for an ever-appreciating home, as the core to one’s retirement, and instead to emphasize what homeownership can provide when compared to renting: more control over the way one lives and the long-term security of being able to stay, weathering the storm of market booms and busts.32 Such models include limited-equity cooperatives, mutual housing, and community land trusts. The financial and governance advantages of joint ownership also enable the exploration of alternate architectural models, as best exemplified by ongoing projects in other high-priced cities, for instance in Zurich, Switzerland.33

Also, in a refreshing change of rhetoric, the candidates are rarely, if ever, speaking of “subsidies”; they are speaking of “investment.” This is significant since it indicates a willingness to question the market as the natural field of operation and metric by which cost, price, and value are determined, acknowledging that direct, tax-revenue-based expenditures in housing create long-term value. Nonetheless, the proposals are still based on somehow correcting or supplementing the market with benefits largely going to those who control that market, not those subject to it.

Shifting from “subsidies” to “investment,” if taken further, could lead to a different conclusion. Instead of working via the private market, public entities could be enabled again to directly develop and manage housing, thereby cutting the various intermediary layers. After decades of privatization of the existing stock of council housing (municipally owned public housing) and a virtual standstill in new construction in the UK, London’s councils—stuck in a housing affordability crisis not unlike that of large US cities—have taken up direct development not only as the most cost-efficient method but as a the best way to control the quality of housing production.34

As bold as the housing plans put forth by the Democratic candidates by mid-September were in scope and framing, the underlying ideas seemed oddly limited, constrained within past patterns of thought, and missing the oomph of a more sweeping reconsideration of the assumptions underlying federal housing policy that the repetition, or constancy, of “crises” clearly merits.

Housing for All

Enter Vermont senator Bernie Sanders. The person who has so fundamentally changed the national conversation on universal health care and universal higher education since he ran for president in 2016 was, until the late summer, curiously absent from the housing conversation. Where was a call for “universal housing”?35 By mid-September, however, Sanders had arrived, with “Housing for All.”36 “Housing for All” does exactly what had been missing to date: it addresses the sticky issues of how the public and private sectors are to relate in housing head-on. But he does another thing his colleagues have not: he connects that conversation to architecture and planning.37 The senator does so through a range of policy proposals, but there are three broad propositions that clearly distinguish him from his competitors.

First, Sanders proposes nationwide rent control. That is, he wants a cap to rent increases across the board, linked to inflation. This is a critical change in the conversation because it addresses everyone, not just the very poor, or the middle class, or the tech worker. It gets to the question of whether housing is a commodity like any easily tradable and nonessential product and should be able to go for whatever the market brings or whether there is something particular to the way its markets function, acknowledging that the market value of a home in large part depends on the public services that surround it.

Second, Sanders has signed on to the notion of “social housing.” This is a concept he adopted from the housing plan generated by People’s Action, a coalition of forty-six housing groups based in thirty states, released just two weeks before Sanders’s own plan.38 “A National Homes Guarantee,” as the plan is called, lays out in terms now well established from the health care debate, what social housing is: “a public option for housing.”39 This means that it is neither the “affordable” we know, created via subsidies to the private market, nor the maligned “public,” restricted to very low income tenants. Rather, social housing, inspired by models prevalent in Western Europe, provides rental or cooperative housing for a broad range of household incomes and is made possible through direct federal funding to municipal housing authorities or locally active nonprofits. Sanders does not give up on “affordable housing” although his plan does say that whatever is produced will, in contrast to current LIHTC regulations, be income- and price-restricted in perpetuity. He also does not give up on “public housing,” calling for the massive capital investment that has been deferred for decades. But in addition to the 7.4 million affordable units he wants to create through the National Housing Trust Fund (that number was given by the shortage of affordable housing diagnosed by the National Low-Income Housing Coalition), and the investment to salvage existing public housing stock, Sanders allows for the comparatively small experiment of two million units of this new “social” type (People’s Action calls for twelve million).

Finally, the third, and perhaps most surprising, aspect of “Housing for All”: specificity for what all of this means in terms of architecture and planning. By making his housing plan an integral part of his climate change plan, Sanders is providing the missing link to productively reframing housing as a design issue. Sanders is the only candidate to explicitly and simply address the energy efficiency both of individual buildings (“decarbonizing”) and of urban planning (“reducing sprawl”).40 For a while, I had been relieved that candidates weren’t invoking specific architectural examples as part of their housing plans, putting the architectural cart before the structural horse. (Remember New Urbanism, which made HOPE VI, the 1990s program to demolish and redevelop “distressed” public housing as historically designed, mixed-income housing palatable?) But then I realized what a relief it was to have Sanders and his team remind us that yes, there is a pretty straightforward role for designers in these political and financial debates.

Sanders falls into traps similar to his colleagues’. He can’t not succumb to the seduction of numbers in terms of unit counts and dollar amounts though his investment will be in the trillions of dollars, not just billions. And Sanders, too, cannot seem to resist the lure of low-income homeownership; even while proposing CLTs, he describes these not as permanent places to live but as merely transitional to an assumed more normal state, for, as he writes, “when those families begin building wealth” they will “move on to conventional homeownership.” His home-flipping tax, adopted from People’s Action, is meant to prevent excessive speculation in the housing market by taxing at 25 percent any increase in value if a property is resold within less than five years from purchase. If the intent is to cool down hot markets, why does it apply only to owners who do not live in the property?41

Even if details of his plan can be debated, Sanders has offered crucial new trajectories to the housing conversation by foregrounding the question of how and where we live, what we pay for it, and who benefits from universal access, a question that affects us all, regardless of place, ethnicity, or income. In a hugely fragmented and polarized political landscape, this is no small feat. He has proposed an alternative to seeing housing as an inevitable by-product of the private market. And he has provided a framework to reposition the importance of design, architecture, and planning in a crisis otherwise largely framed in socioeconomic terms. Shrinking, prefabricating, or other preferred architectural strategies that purport to lower the price (rent) of housing rarely do, even if they bring down the cost of production.42 But demanding housing that is built to higher standards—ones defined by energy efficiency and located in areas reached by public transit—without resorting to stylistic or other market-oriented tropes, is a liberating way for architects to address affordability and fairness.

The conversation is changing very, very fast. Architects, get on board.

-

“Changing the conversation” has been a central goal of the housing research spearheaded by Columbia University’s Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture, including its work on public housing in the immediate aftermath of the 2008 mortgage crisis. For a summary of that work, see their publication Public Housing: A New Conversation (2009), link. I was lead researcher and co-curator of a later Buell Center project on housing, House Housing: An Untimely History of Architecture and Real Estate, and co-author of a related publication, The Art of Inequality: Architecture, Housing, and Real Estate—A Preliminary Report (2015). Avery Review contributing editor Jacob R. Moore is the Buell Center’s associate director. ↩

-

It was only twenty-five years ago that Massachusetts voters banned the option of allowing municipalities to set caps on rent increases in a statewide referendum. In the thirty-seven states where limits on rent increases remain outlawed, this rests largely on the argument that it infringes on private property rights. For an overview, state by state, municipality by municipality, see National Multifamily Housing Council, “Rent Control Laws by State,” last updated September 20, 2019, link. ↩

-

For an in-depth case study of the effects of and fight against exclusionary zoning, see Douglas S. Massey et al., Climbing Mount Laurel: The Struggle for Affordable Housing and Social Mobility in an American Suburb (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013). ↩

-

The process included the Making Room initiative, a research and exhibition project spearheaded by the Citizens’ Housing and Planning Council, in collaboration with the Architectural League of New York. I contributed to this initiative as part of Team R8, one of five architectural teams invited to test the regulatory limits of housing. The project is documented at this (link: https://chpcny.org/research/making-room](https://chpcny.org/research/making-room text: link). This work led to a pilot project to test the viability of shrinking the minimum legal unit size, implemented as Carmel Place by nArchitects and Monadnock Construction. The minimum unit size was subsequently adjusted as part of the Zoning for Quality and Affordability revisions to the Zoning Resolution in early 2016. Minimum unit size was decreased from 400 to 325 square feet, but only for affordable senior residences. See: link. ↩

-

NYC Housing Preservation and Development, Share NYC RFI RFEI, “Designation,” link. ↩

-

A standard measure of the affordability of homeownership is the ratio of median home price to median household income in a particular area. Nationwide, this rose from a low of 3.3 in 2011 to a 4.1 in 2018. The peak was 4.7 in 2005. In coastal cities, this ratio can be more than 5.0. Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, The State of the Nation’s Housing 2019 (June 2019), 2. ↩

-

See for example, Shirin Gaffary, “Even Tech Workers Can’t Afford to Buy Homes in San Francisco,” Vox, March 19, 2019, link. ↩

-

Two policy research institutes tend to provide the statistics cited in the discussion around housing. The first is the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University, which publishes a yearly report, The State of the Nation’s Housing. The last one was released in June 2019: link. The Low-Income Housing Coalition publishes The Gap Report . Its latest version was released in March 2019: link. ↩

-

Although calculations vary, most sources cite a 1:10 ratio, namely, that the median black family wealth is $17,600 whereas the median white family wealth is $171,000. See, for example, Trymaine Lee, “A Vast Wealth Gap, Driven by Segregation, Redlining, Evictions, and Exclusion, Separates Black and White America,” New York Times Magazine, August 14, 2019, link. ↩

-

For an overview of the evolution of the role of the federal government in housing policy, see Alex Schwartz, Housing Policy in America , Third Edition (London: Routledge, 2015). See Allen Hays, The Federal Government and Urban Housing, Third Edition (Albany: SUNY Press, 2012) for a more philosophical and ideological analysis of these policies and programs; and see John F. Bauman, Roger Biles, and Kristin Szylvian, eds., From Tenements to the Taylor Homes: In Search of an Urban Housing Policy in Twentieth-Century America (State College: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000) for the perspective of urban and architectural historians. ↩

-

While the US Congress was never particularly keen on allocating resources to the new construction of public housing, the amount has steadily decreased since the mid-1970s. The 1999 Faircloth Amendment barred local housing authorities from expanding the number of public housing units. ↩

-

On these and other housing issues, see the excellent reporting by Kriston Capps, for instance, “How HUD Could Dismantle a Pillar of Civil Rights Law,” CityLab, August 16, 2019, link, or “The Brutal Austerity of Trump’s 2020 Budget,” CityLab, March 11, 2019, link. ↩

-

For a short history of the role of philanthropy in late nineteenth-century US housing reform, see Eugenie Ladner Birch and Deborah S. Gardner, “The Seven-Percent Solution: A Review of Philanthropic Housing, 1870–1910,” Journal of Urban History, vol. 7, no. 4 (August 1981): 403–438. ↩

-

Scott Greenstone, “Amazon, Microsoft, and Others Give Tens of Millions for Homeless Services,” Seattle Times, June 11, 2019, link. For a more in-depth analysis of Amazon’s overall philanthropic philosophy, see Gaby Del Valle, “Jeff Bezos’s Philanthropic Projects Aren’t as Generous as they Seem, Vox, November 29, 2018, link. ↩

-

The inversion of these architectural tropes is captured in Richard Florida’s spin on the term “urban crisis,” associated with the disinvestment and racial segregation of US cities fifty years ago, to diagnose the territorial reversal today. Richard Florida, The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class—and What We Can Do about It (New York: Basic Books, 2017). For a succinct reflection on the emergence of “the urban crisis” as a concept in the 1960s and 1970s, see Wendell E. Pritchett, “Which Urban Crisis? Regionalism, Race, and Urban Policy, 1960–1974,” Journal of Urban History, vol. 34, no. 2 (2008): 266–286. ↩

-

Lawrence J. Vale, After the Projects: Public Housing Redevelopment and the Governance of the Poorest Americans (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019).

Stubborn Assumptions

It is important to recognize what a fundamental shift this focus on affordability and fairness in the debate over housing in the United States is since there are, and have been, many other ways of framing a housing crisis, and many other policy recommendations that result.[^17] Federal action in housing has been justified as a means to jump-start the national or local economy (“housing starts” and “household formation” remain key indices of how well the economy is doing), combat unemployment (through construction jobs, as in the New Deal), ensure public health (“slum clearance” in the Progressive Era), promote technological innovation (as in wartime experiments in prefabrication or new materials), or win Cold War battles against communism (homeownership). ↩

-

Cory Booker, “Cory’s Plan to Provide Safe, Affordable Housing for All Americans,” Medium, June 5, 2019, link. ↩

-

Amy for America, “Senator Klobuchar’s Housing Plan,” Medium, July 25, 2019, link. ↩

-

Some candidates had not addressed housing at all by late September, among them former vice president Joe Biden. His campaign website in general refrains from outlining any detailed plans, instead invoking simply “Joe’s vision,” (link: https://joebiden.com/joes-vision](https://joebiden.com/joes-vision text: link). Former entrepreneur Andrew Yang might have given himself an easy excuse for abstaining from the conversation around housing since his “Freedom Dividend” could be pitched as replacing down payment assistance, renters’ tax credits, and rental vouchers in one go. Yang’s only reference to housing is relating the affordability crisis to zoning, where he says, “Home ownership is a part of the American dream.” Yang 2020, “Policy: Zoning,” link.

Supply

More or less all of the candidates assume that that housing prices are a question of supply and demand, and therefore that increased supply will lead to more affordability. They rarely distinguish between “affordability” in all housing, including so-called market-rate housing, and “affordable housing,” which refers, in its current usage, to housing targeted at certain income groups only and whose price is set accordingly, or “below market.” Hence Massachusetts senator Elizabeth Warren calls for “building millions of new units.” She continues: “My plan will bring down rental costs by 10 percent by addressing the root causes of the problem: a severe lack of affordable housing supply, and state and local land-use rules that needlessly drive up housing costs.”[^23] Warren is not the only one to cite “millions” of new “units of housing,” made possible by “billions” of federal dollars coupled with a parallel loosening of local zoning restrictions as well as increased tenant protections. It’s the result of an age-old and well-worn political calculation: the urgency is huge, we have to do something, so let’s build, and in parallel get rid of some of those pesky regulations which drive up cost, or introduce regulations to limit NIMBYism![^24] Housing units can be counted, touched, photographed—never underestimate the appeal of a groundbreaking photograph, shovel in hand, or the smiling faces of the family lucky enough to have been selected for one of the new apartments.[^25] ↩ -

Alexander von Hoffman, “Calling upon the Genius of Private Enterprise: The Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968 and the Liberal Turn to Public-Private Partnerships,” Studies in American Political Development, vol. 27, no. 2 (2013): 165–194. ↩

-

For a more detailed story of how focusing on housing production can, in fact, counteract political and economic change, told in light of New York City’s experience with the federal Model Cities program, see Susanne Schindler, “Model Conflicts,” e-flux Architecture, July 2018, link. ↩

-

For an example of this reading, see Thomas Crogwell, “#8: How Carter Lectured, Not Led (Top 10 Mistakes by U.S. Presidents),” Encyclopedia Britannica Blog, January 14, 2009, link. ↩

-

If, when, and where increased supply brings down overall housing prices, and where it causes rising prices, is a broad field of research. For a nuanced article attempting to address “supply skeptics” like myself, see Vicki Been, Ingrid Gould Ellen, and Katherine O’Regan, “Supply Skepticism: Housing Supply and Affordability,” Housing Policy Debate, vol. 29, no. 1 (December 2018): 25–40, DOI: 10.1080/10511482.2018.1476899.

Homeownership

A second unchallenged assumption embedded in the candidates’ housing plans is that individual homeownership is a, if not the, key to building wealth in the United States. They cite the enormous wealth gap between white and black Americans, created, in large part, due to the exclusion of minorities from many of the federal housing policies launched in the New Deal, including mortgage insurance, as well as the negative effects of redlining, compounded generationally since. Hence candidates are proposing to redress these past ills by creating paths to homeownership for those previously excluded. In so doing, they are buying into the assumption that equity (in the form of real estate) is the best path to equity (in the sense of access to social and political power) because real estate is assumed to appreciate in terms of market value over time. ↩ -

Booker, “Cory’s Plan to Provide Safe, Affordable Housing for All Americans.” ↩

-

Kamala Harris for the People, “Combatting the Racial Homeownership Gap,” link. ↩

-

Yang, “Policy: Zoning.” ↩

-

Harris, for example, writes, “And to ensure these new homebuyers have the necessary financial literacy to stay in their homes, we’ll increase funding for the Housing Education and Counseling (HEC) program.” See link. ↩

-

Lack of oversight on the part of HUD, deliberate and not, allowed private developers to deceive low-income minority homebuyers through shoddy renovation at no financial risk of their own. Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019). ↩

-

Buttigieg is certainly not the first to invoke “homesteading” as part of an effort to “revitalize” cities or neighborhoods suffering from disinvestment. Similar efforts prevailed beginning in the mid-1970s in small and large cities alike, and in many cases proponents actively cited the “frontier” or “pioneer” mentality in a seemingly positive sense. For a recent critical assessment, see Marisa Chappell, “The Strange Career of Urban Homesteading: Low-Income Homeownership and the Transformation of American Housing Policy in the Late Twentieth Century,” Journal of Urban History (February 2019), 1–28, DOI: 10.1177/0096144218825102. ↩

-

Various studies have shown that homeowners in limited-equity models have lower delinquency and foreclosure rates than so-called conventional homeowners. See the research summarized in Brett Theodos et al., “Affordable Homeownership: An Evaluation of Shared Equity Programs,” The Urban Institute, 2017, link. ↩

-

There has been ample coverage in the architectural press of recent examples of Genossenschaften and Baugruppen in Zurich but also Berlin and Vienna. I will simply point to an article of my own, “Housing and the Cooperative Commonwealth,” Places Journal, October 2014, link.

Subsidies

The third tenet that undergirds most candidates’ housing plans is that, for those who still cannot make the rent or do not have enough to make the down payment on a house, the government will provide subsidies to the private and nonprofit sectors. That model—like food stamps, aka SNAP—can work, if it is seriously scaled up. Hence Castro’s proposal to “ensure that every family who needs a voucher will receive one,” meaning that he would remove a cap on the maximum number of households who get the subsidy.[^38] For those who make too much to qualify for a voucher but still can’t afford the rent, he introduces a new “renters’ tax credit” to refund individuals for housing costs that go beyond 30 percent of their income, something that Harris and Booker also propose.[^39] Making housing vouchers an entitlement and expanding other existing programs, like low-income housing tax credits, are solid proposals. ↩ -

For an overview, see Michael Kimmelman, “New York Has a Public Housing Problem. Does London Have an Answer?” New York Times, March 1, 2019, link. ↩

-

For posing the question of “universal housing” in relation to Sanders’s other policy proposals in 2016, I credit architectural historian Juliana Maxim, author of the recently published The Socialist Life of Modern Architecture: Bucharest, 1949–1964 (London: Routledge, 2019). ↩

-

Sanders’s is not the first plan to use the trope “for all” or to call for a return to direct federal investment in national housing policy. In July of 2018, the liberal think tank Center for American Progress released its “Homes for All” proposal. With a goal of 1 million new units in five years, the plan is far more limited in scope than the twelve million units called for by People’s Action (see note 44). However, it too argued for a retake on the original promise of public housing in this country: a far more broadly defined constituency, not just the very poor, and better design as the basis for long-term affordability. In a conversation with the author in August of 2019, Michela Zonta, the report’s author, stated that CAP writes plans with members of Congress in mind. In the summer of 2018, many took interest in the plan but considered its call for direct federal action as far “too bold.” A little over year later, this sounds, instead, quite timid. The report is available at link. ↩

-

No candidate comes up with a plan on his or her own. Plans are works of collaboration, compromise, and political calculus. Sanders had the farsightedness to adopt many of the nuanced and well thought out recommendations of People’s Action. See link. People’s Action, who started working on ways to make housing part of the 2020 election cycle in the summer of 2018, in turn brought in other expertise. As Daniel Aldana Cohen described the “tributaries” to the proposal to the author in a conversation in October 2019, People’s Action encountered the concept of “Social Housing in America” in a proposal of the same name put forward in the spring of 2018 by the think tank People’s Policy Project, and one of its authors, Peter Gowan, subsequently became a member of its research and writing team. See link. Daniel Cohen became part of the team on the basis of his piece “A Green New Deal for Housing,” published in Jacobin in February 2019, in which he argues that we cannot solve the climate crisis without also solving the housing crisis, and vice versa: link. ↩

-

People’s Action, A National Homes Guarantee: Briefing Book, September 5, 2019, 4 link. ↩

-

Sanders could have gone further and taken more substantial suggestions from People’s Action. Under the heading “Design,” the plan itemizes elements as specific as which amenities should be provided on the ground floors of new housing to recommendations for street design and amount and location green space. A National Homes Guarantee, 5. ↩

-

Sanders, “Issues: Housing for All.” ↩

-

I have argued the point that savings in construction cost do not necessarily translate into lower prices to the consumer in a review of two housing exhibitions in 2015, “Affordable Housing Appraised: A Review,” Urban Omnibus, December 14, 2015, link. More specifically, Elizabeth Greenspan’s review of Carmel Place, the micro-unit pilot project referenced above, provides hard data. Greenspan points out that the resulting units are cheap only when designated “affordable,” that is, income- and price-restricted. The building’s market-rate units, however, are renting at higher rates than comparable units. All this, despite shrinking unit size and prefabricating building components. Elizabeth Greenspan, “Are Micro-Apartments a Good Solution to the Affordable Housing Crisis?” The New Yorker, March 2, 2016, link. ↩

Susanne Schindler is an architect and historian interested in how design, policy, and finance intersect in housing. She is currently a visiting lecturer at MIT and co-directs the MAS program in the history and theory of architecture at ETH Zurich.