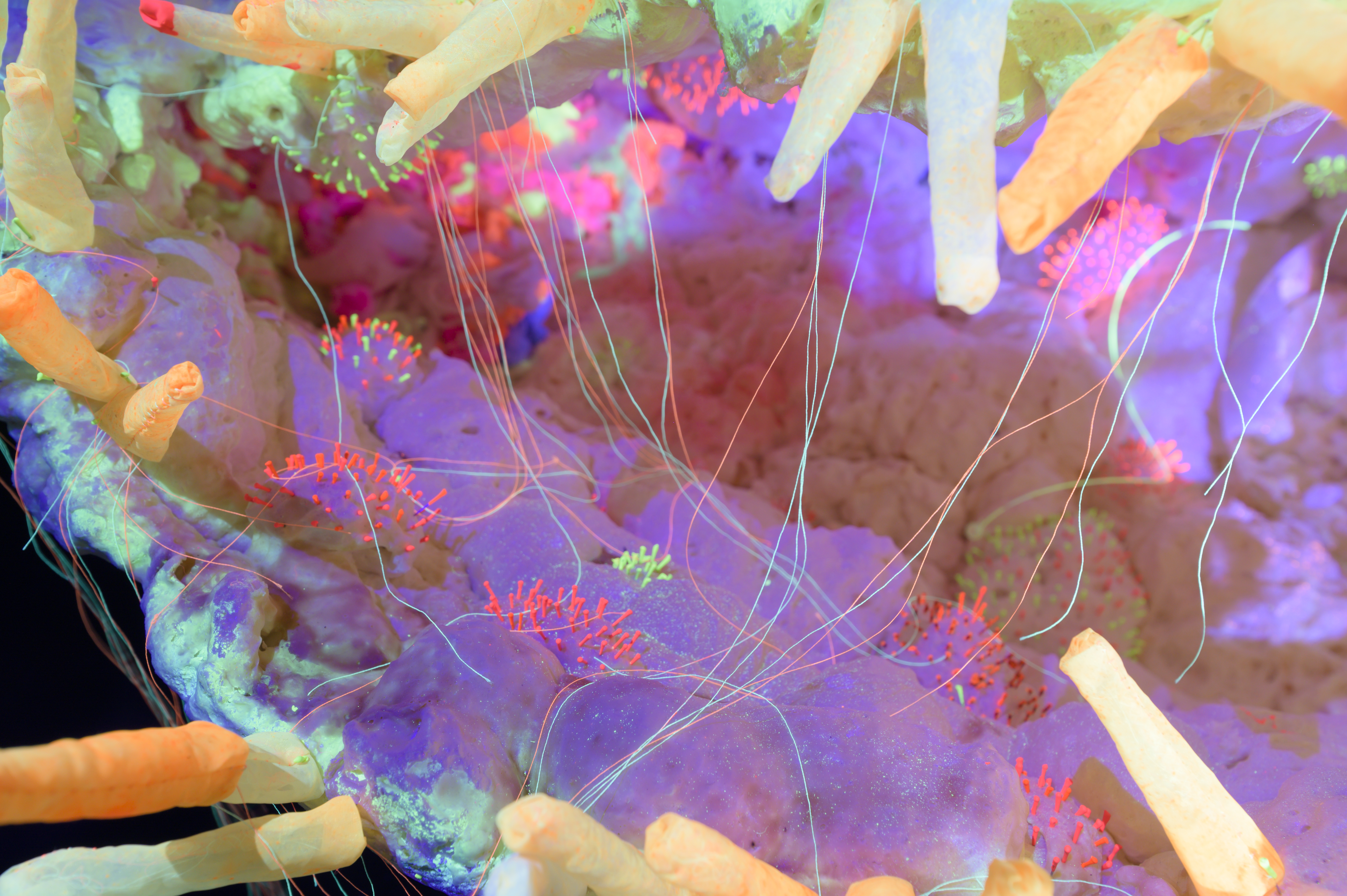

It was while swimming in the waters off the coast of the Greek island of Milos that I first considered my relationship with the ocean to be erotic. As my body floated in the deep blue mass, I felt a strong desire to be fully immersed in it, absorbed by it, one with it. Anne Duk Hee Jordan’s video Ziggy and the Starfish (2016–2018) made me connect this aquatic sensation to more-than-humans. The film conjures an image of multispecies intimacies emblematic of the way queer ecology, or the erotic more-than-human longing I call “sex ecologies,” presses increasingly to the fore in artists’ works.1 Her moving image collage depicts luscious anemones, caressing sea slugs, and spawning corals, accompanied by underwater sounds and songs from vintage erotic movies. These trans-species resonances, to me, are deeply sensual. They push into the edges of my “self,” tingling beyond the boundaries of my own already multispecies body.

It was poet and classicist Anne Carson who helped me find words to put to the feeling of bodily and psychic longing toward the ocean. In her book Eros the Bittersweet (1986), Carson identifies desire as a three-point circuit. It is composed of the lover, the beloved, and the difference between them producing an absence that goes, paradoxically but necessarily, hand in hand with sensuous connectivity. It is this gap that evokes eros as “deferred, defied, obstructed, hungry, organized around a radiant absence,” as Carson defines it.2 “Eros is an issue of boundaries,” she continues. Eros makes me long to dissolve my edges but at the same time it hinges on these very boundaries and the realization that my edges will never fully dissipate.3

While Carson writes eros into human relations, in this essay I expand this longing to nonhumans, including the ocean. How exactly is my relationship with the ocean erotic? Diving into this question, I will further ask: Could the current environmental crisis, fueled by our mishandlings of the thing we call nature in the Capitalocene, be connected to a fear of the erotic? In the following, drawing on Carson’s as well as other writers’ and artists’ engagement with the erotic and extractivism, I bring those notions together to speculate about whether the hungry longing for a radiant, absent other triggers a deep fear of the loss of control over nature. I ask whether, by recognizing eros and celebrating it in our relations with nature, we can foster more caring connections with all planetary beings, including the oceans.

Ocean Extractivism

Deep-sea mining is one of the imminent dangers facing the oceans and manifold lifeways, both human and nonhuman. This novel form of extraction uses heavy machinery to remove rare earth minerals such as manganese from the soft sediments of the seafloor. The procured metals are used in the production of technologies such as touch screens, as well as renewable energies like rechargeable batteries. Among the targeted minerals are sulfides that develop over millions of years near geologically active hydrothermal vents. These underwater “volcanoes” are far from lifeless. They support yeti crabs, scaly-foot snails, and numerous other deep-ocean creatures. Indeed, it is thought that the last universal common ancestor to life on Earth could have thrived on the iron- and sulfur-rich smoke.4 But we still know very little about these ecosystems and their ecological function, which renders deep-sea mining endeavors incredibly risky.

Deep-sea excavations are conducted within a complex web of ecology, jurisdiction, technology, and activism.5 The administration of deep-sea mining licenses and regulations is handled by organizations such as the United Nations in New York and the International Seabed Authority in Kingston, Jamaica. Research is sponsored by industry, as well as by national governments such as Germany, Norway, and Canada, with support from countries where mining is planned to take place, including Nauru and Papua New Guinea. At the same time, mining activities are countered with fierce grassroots opposition by citizens concerned with their ecological and social impact.

In Papua New Guinea, mining operations targeted the waters off the coast of Karkar Island in the Bismarck Sea, away from the attention of those not immediately affected. Since the now defunct Canadian underwater mining company Nautilus first came to Papua New Guinea in 2008, technological failures, economic miscalculations, and fierce grassroots protest movements have put a halt to these endeavors. However, this pause is likely only temporary. Demand for rare earths and metals is rising, with diminished supply and staggering prices. In March of this year, The Metals Company announced that they are pushing for mining in the Clarion Clipperton Zone in the Pacific to start as early as 2024.

Deep-sea mining is not only removed from the mainland, it also takes place far away from the seats of power in the Global North (though mining companies are usually headquartered there). Social science and cultural studies scholar Macarena Gómez-Barris uses the term “extractive zones” to critique this “colonial paradigm, worldview, and technologies that mark out regions of ‘high biodiversity’ in order to reduce life to capitalist resource conversion.”6 Advocates of deep-sea mining commonly state that it will have a lesser ecological impact than land-based mining. They offer up the idea that the ocean floor is distant from land and that the affected areas are fixed and containable.7 Deep-sea mining regulations require that protected recovery areas are set aside next to mining zones. The environmental impact is supposed to stay localized. Edges clearly demarcated. But mining effects move with water currents and shifting sediments, and organisms are part of a wider, deeply interconnected ecosystem.

Not an Island

Centering on land-based phosphate mining on Banaba in Kiribati, Pacific scholar, artist, and activist Katerina Teaiwa astutely critiques the exploitative colonial, capitalist policies and environmental and social effects of extractivism. Banaba is an island marked by British, Australian, and New Zealand agricultural imperialism. During World War II, Japanese forces massacred all but 200 inhabitants, and forced the displacement of most Banabans to Rabi Island, Fiji, after 1945. In her writing and artistic work, Teaiwa denounces the reduction of human and nonhuman life to capitalist resources benefiting colonial forces, with the ecological and social costs off-loaded to Banaba’s people and ecosystems. She rebukes the ranked stratum not only of whose life is affected but also between life and nonlife, arguing that “phosphate rocks and islands are also not static lumps.”8 Contrarily, proponents of seabed mining consider deep-sea minerals as nonliving, passive, and extractable. But the edges between North and South as well as between life and nonlife are not so easily drawn. The uneven flows of global capitalism play out on a planetary scale, and deep-sea metals grow in biological-geological interdependence. Their extraction puts living ecosystems at risk far beyond the borders of extractive zones.

Whether on land or in the deep sea, the physical and conceptual edges drawn around extractive zones resemble the perimeters of islands, conceived as singular entities that are separated both from water and from each other. The concept of the island is indeed the product of imperialist thinking emanating from the European continent.9 As in other colonial endeavors, conceiving islands and the deep sea as extractive zones, and extractive zones as containable, fixable, inanimate, and remote, begs the question: Separated and remote from what and for whom?

In an influential essay from 1993, the late Tongan and Fijian writer and anthropologist Epeli Hauʻofa advocated for a reappraisal of this compartmentalizing worldview. His writing conceives Pacific nations not as small specks of land in a vast ocean but as a large “sea of islands.” With this reversal, Hauʻofa offers “a more holistic perspective in which things are seen in the totality of their relationships.”10 Three thousand years ago, people from New Guinea, Tonga, and Samoa were moving among the islands in ways more interconnected than ever until the current age of mass transportation.11 Water connects rather than divides, but this connectivity does not unify the ocean in a homogenizing sense. Neither does it eclipse borders, migration policies, and economic limitations to travel. In Hauʻofa’s oceanic thinking, the specificities and differences of all interconnected entities are defined by their relationships with one another.12 He offers a reconfiguration of the edges between land and sea that in European conceptions are clearly demarcated. In Hauʻofa’s writing, the vast world of Pacific islands is composed of boundaries in negotiation, where water washes on the shores, shipborne travelers denounce borders as fictional, and connectivity threatens to dissolve the colonial cartographic grid stratifying land and water alike. In this understanding, edges are complicated by relationality and proximity.

The Oceanic Edges of Our Skin

I am writing these words as a leisurely swimmer in the Mediterranean. Water envelops me. It touches me all over as I become part of its toxic and simultaneously reproductive soup of ova, spermatozoa, feces, and pollutants.13 All these forces, at once cultural and biological, touch me; some of them change me, while others pass unregistered. Nutrients, pollutants, and increasingly the chemical reactions caused by warming ocean temperatures due to the climate disaster permeate water and skin.

I wonder, then, what kinds of other worlds we can conjure through experiences pushing against the edges of our bodies, islands, the ocean, and other conceptual divides. Water lends itself to exploring this question. Anne Carson knew this too. In the essay “Water Margins,” she describes weeks of swimming and standing at the shores of a lake with her brother, observing the water and bodies immersed in it, both human and nonhuman: “The lake is cool and rippled by an inattentive wind. The swimmer moves heavily through an oblique greenish gloom of underwater sunset, thinking about his dull life.”14 Carson can be brutal sometimes. Her words pierce right through our edges. And yet, in this text the position of the author shifts. She writes as her brother-as-swimmer, taking on his point of view. She is swimming in his skin.

The skin is our edge with the world, but it is a leaky boundary. Feminist theorist Karen Barad contends that our relationship with nonhumans means “having-the-other-in-one’s-skin.”15 We inhabit our skin, yet what we call skin is not ours alone, but an organism co-composed of many microbial bodies, each with their own permeable skin.16 Our bodies do not end with our skin, just like islands do not end with the outer perimeter of land but extend with continental shelves, with migrating humans bringing with them their place-based stories, and with the effects of mining seeping into other geographies and futures.

Difference as Commitment

Our fuzzy edges move against bodies of water, bacterial and other nonhuman bodies, and the human bodies we desire, each forming infinite erotic triangulations. In beautiful prose that to me is itself erotic, gender studies scholar Eva Hayward describes a sensation of deeply felt connectivity as she wades into the ocean:

My feet and ankles and calves touch innumerable organisms: dinoflagellates, radiolarians, diatoms and other lively bits like fertilized eggs looking for a home or wayward sperm. My cells are alert to the seawater and its changing salinity, perhaps even absorbing the elements as some of my own skin sheds into the roiling lip of surf. I am not the ocean, but in this moment I am with the ocean. Our differences are obvious and deep, but my own genetic code is a fleshy spine of marine legacies. All of us are partly coral reefs full of developing polyps, growing sponges, brooding anemones and feeding sea snails.17

Even as we are all partly coral reef, we are also not the ocean, and our differences run deep. Feminist, queer, and race studies scholar Sara Ahmed highlights the importance of recognizing differences and guarding their particularities from generalizations and violent conflations. Writing about gender and sexuality, Ahmed warns of binary reductions. We can transfer her thinking to the ocean. It is in seeing the ocean as marked by differences, rather than as a mark of difference, that I am endlessly obligated to it.18 Its differences do not exist as a mirror in which I assert my own position in a dyad, nor are any of those differences given priority over others. Recognizing the ocean’s specific differences generates an ethical singularity and complex relations I can neither fix nor keep at arm’s length. This commitment extends across aesthetic, material, historical, and political specificities, not as a burden but as a sustaining bond. This bond resists the clear-cut edges produced by deep-sea mining and other forms of extractivism. Borders around mining areas are permeable. Extractive zones in the Global South also leak into the Global North. Our bodies do not end with our skin. Our intentionality reaches far beyond us in time and space, just as other matter and intentionalities press into us, affecting us and others.

For Ahmed the ethical experience of interacting with another as other is crucial. While I have the ocean in my skin, that does not make it mine, nor does it make it less itself. Some of its particles enter my body while our differences spur my longing for more. The triangular constellation that Carson identifies as eros—in this scene myself, the ocean, and the difference between us—stirs a deferred, hungry, radiant absence. That, to me, is deeply erotic. This oceanic erotic ethically and ontologically challenges the notion of cleanly demarcated extraction from a remote other, since even though we are not the same, the ocean and I are deeply connected, and mined minerals do not only leave a cut in the seabed but draw a cut through my skin as well.

The ocean’s differences need to be cared for. I sense here the modest beginning of an alternative formulation of sustainability, where it is not defined by fixed relations and attempts to fully master those relations, but by accepting the ocean’s otherness and unknowability. Anne Carson wrote that love can be predatory, and that attempts to seek knowledge—and, I would argue, sustainability—can be too. Eros as unattainable longing accepts the difference between myself and the other I desire, be it another human or the ocean. In fact, eros requires this difference, even as it exceeds understanding. Sustainability founded in the erotic is based on the acceptance of difference—beyond the forms of management visible, for instance, in the separation of mining zones from protected areas in futile attempts to control leaky boundaries.

Shoals of Intense Proximity

The erotic can occur in encounters between bodies both human and nonhuman, terrestrial and aquatic, natural and synthetic, concrete and abstract, as well as on a planetary scale. But even as eros hinges on radiant absence, as Carson says, it requires proximity. Proximity produces relationality. Embodied presence and movement in water enable affective interactions.19 In close encounter, be it physical or conceptual, we can feel that we are partly coral reef as much as we are different from the ocean.

But difference is not equivalent to distance. As Epeli Hau‘ofa shows, in most European conceptions of the ocean—as well as in cartographies making land and water appear entirely distinct—its aquatic mass is thought to be that which divides, rather than that which connects.20 If proximity produces relations—porous, entangled, and shifting—then distance is a project of scales that requires fixed positions between bodies and places. The project of Western progress was bolstered by distancing from nature and the extractive zones of the colonies through physical and conceptual separations.21 In this conception, bodies are only allowed to enter the skin of others through various modes of consumption. This distance was simultaneously intended to be overcome through European trade and migration spreading across the globe and upheld to proffer the imperialist strategic distinction of the Old from the New World. Colonialism and capitalism continue to conceive the ocean as a traversable, smooth space. But imperialism has hardly ever been hindered by remoteness, and today the ocean remains a striated place, with infrastructures and navigation points designed to fix and organize water like land.22

Challenging these modern edges, Tiffany Lethabo King, a gender studies scholar working at the intersection of African diaspora and settler colonialism, offers the geologic formation of the shoal. She considers the shoal as a liminal and errant ecotone that is hard to map, thus defying the permanence of cartographic edges. The shoal requires slowing down and navigating new footings that consider sea and land as well as shifting sand, together thereby disrupting colonial geographies as much as Western philosophies and ways of being that are based in separation and distance.23 Similarly, poet and South Pacific Studies scholar Teresia Teaiwa (late sister of Katerina Teaiwa) asks: “Where is the edge in the Pacific?… Is it on a beach…? Is it on the horizon…? Is it on… tectonic plates?”24 Proximate engagement with the moving edges of the ocean destabilizes fixed positions and scales in favor of more complex and ethical relations.

There is nothing erotic in the colonial insistence on distance and independence. Approximations here are not meant to produce intense proximity—defied, obstructed, and hungry, as Carson writes—but they are at best transactional and more commonly exploitative. My desire for the ocean is not only a wish for closeness and relations over divides, it is also necessity, dependence even. Perhaps this is the moment to state the obvious: We all depend on the ocean for survival. An oceanic erotics can bring us closer to bodies, including bodies of water. My longing for the ocean knows that I can never fully grasp it, and that its edges shift, like those of shoals. But erotics does not need to know a finite body to desire.

The Edges of Desire

Where environmental humanities scholars mostly look to the Enlightenment nature/culture divide to understand the modern separation of the human and nonhuman, Anne Carson draws our attention to an earlier pivotal moment. In the eighth century BCE, a major change in the conception of self occurred in ancient Greece, ushered in by the invention of an alphabet that included not only consonants but also vowels during the transition from oral to written culture. Spoken culture requires continuity since sentences cannot be set aside for later retrieval in the same way they can be in written language. Spoken words flood our perceptions. Sound produces a continuous flow, brought about through breath (life). In contrast, Carson says, written culture creates edges. Words are separated from one another on paper, syllables are discrete, letters are distinct, and writer and reader do not have to be in the same space for a story to be told. Writing and reading require focus, they demand that we isolate vision from all other senses—hearing, smell, touch, and taste. For the ancient Greeks absorbed in written attention, eros is perceived as an overwhelming force flooding in. Its arrival produces an existential moment, a threat even.

Elsewhere Sara Ahmed suggests that it is precisely the fear of a perceived threat caused by the presence of an “other” that works to effect the boundaries between self and other.25 Political philosopher and environmental engineer Malcom Ferdinand shows that fear, in the case of his writing both of humans living differently as well as of nature, evokes altéricide: “the denial of the possibility of living on Earth in the presence of an Other.”26 The other—other humans, the ocean—is denied existence, it is eradicated or subordinated to comply with hegemony or to become a resource in the extractivist sense, as is evident in deep-sea mining, for example.

Back to writing, Ahmed proposes an ethical engagement with text as one “which caresses its forms with love.”27 An ethical reading does not replicate the violence of distant universalism or objective truth independent of context but is based in complex and shifting relationality and engagement. In ethical reading, subject and object can merge temporarily—as in Barad’s having-the-other-in-one’s-skin, or Carson’s merging of her and her brother’s perspectives—without annulling the differences that mark them. I am not the ocean. But its otherness does not pose a threat to me either.

Recall that it is at the edges that eros occurs. Indeed, Carson shows how eros pushes us to our own edges as we try to overcome the absence between lover and beloved. As I swim in Milos, I sense the edges of my body tremble. Other bodies pass through me, but where I long to be one with the ocean, we remain distinct. This erotic absence marks the singular relationship between myself and the many bodies composing the ocean. At the same time that I push into it, the ocean presses into me. It is easy to wish to give up the self in this mass of blue. Surrounded by azure water, I wonder if the ancient Greeks’ anxieties, over losing the logocentric self to eros as it floods the focused space of the reader and inundates words neatly divided on a page, mirror the moderns’ fears of coming too close to nature. Could the rationales bolstering extractivism, based in separations, in distances, in the will to preserve boundaries of self and other—including other humans and nature—be not only imperialism par excellence but a problem of erotophobia? Ecofeminist scholar Greta Gaard shows that the fear of the erotic is founded in divisions, naturalizations of sex and sexualizations of nature, as well as numerous depreciations of “Others”: “Western culture’s devaluation of the erotic parallels its devaluations of women and of nature,” which these devaluations mutually reinforce.28

What if we didn’t fear, but desired, the ocean? In Audre Lorde’s essay “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” from 1978, the Black feminist poet and activist conjures the erotic as a source of power and knowledge arising from deep within women.29 Lorde writes that in Western society, we have learned to be suspicious of this resource. I agree with her: the erotic is power. In pushing us to our edges, as Carson suggests, I wonder if the erotic can help us relate differently. We can find inklings of new forms of relating in poet and activist Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s pleading with saltwater and corals to “dream until your edges soft,”30 and in Anne Duk Hee Jordan’s gently caressing sea slugs that come close to dissolving my edges altogether. Thinking about edges as she writes from the rim of a high cliff, Teresia Teaiwa proposes a similar critique of their impenetrability:

From the edge, the islands look restricting. Look backward. Look embarrassing… From the edge you can take what you want from the islands—the colors, the food, the memories. You can leave what you don’t want behind—the politics, the problems, the obligations. From the edge, the islands can sometimes look liberating. Look exciting. Look promising… Is it possible to have an edge in the world’s largest ocean?31

What if we swim with the erotic? What if we pursue it, rather than fear it? The erotic ocean softens our edges, like Lethabo King’s shoals. In the erotic ocean, we relate in intense proximity. The erotic ocean floods the edges of my desire. It is a different other passing through me, that I long for but know I won’t ever fully understand, nor one that I want to own or exploit. Carson writes that desire moves; eros is a verb. In the erotic ocean, we move with its waves.

-

I am currently a project co-leader (with artist Katja Aglert) for the exhibition Sex Ecologies, a joint project by the art center Kunsthall Trondheim in Norway and the environmental humanities collaboratory The Seed Box at Linköping University, and editor of the eponymous book exploring queer affect, sexuality, and sustainable care in more-than-human worlds. The term “sex ecologies” is more suitable here than queer ecologies as we explicitly aim to push back against patriarchal-colonial definitions of sex and the shame associated with it in Western cultures. Feminist environmental humanities scholar Catriona Sandilands has been key to defining queer ecology; see, for instance, Catriona Sandilands and Bruce Erickson, “Introduction: A Genealogy of Queer Ecologies,” in Queer Ecologies: Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire, ed. Catriona Sandilands and Bruce Erickson (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), 1–50. See also Greta Gaard, “Green, Pink, and Lavender: Banishing Ecophobia Through Queer Ecologies,” Ethics and the Environment 16, no. 2 (Fall 2011): 115–126; and Noreen Giffney and Myra J. Hird, eds., Queering the Non/Human (London: Routledge, 2008). ↩

-

Anne Carson, Eros the Bittersweet (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986), 18. ↩

-

Carson, Eros the Bittersweet, 30. ↩

-

Keith Cooper, “Looking for LUCA, the Last Universal Common Ancestor,” Astrobiology at NASA, March 30, 2017, link. ↩

-

I curated photographer and filmmaker Armin Linke’s research project “Prospecting Ocean” (2016–2018), commissioned by TBA21–Academy, on this topic at the Institute of Marine Sciences of the National Research Council of Italy (CNR-ISMAR) in Venice. In the book Prospecting Ocean (Cambridge and London: MIT Press and TBA21–Academy, 2019), I further unpack the paradigms at play in ocean extractivism through the lens of artists’ work. ↩

-

Macarena Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), xvi. Scholar of Indigenous education Linda Tuhiwai Smith shows how European “discoveries” in the colonies turned and continue to turn Indigenous knowledge into commodities in the same way that land is turned into mines. Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (London: Zed Books, 2012). ↩

-

See the way Impact Reference Zones and Preservation Reference Zones are described by the International Seabed Authority: “Design of IRZs and PRZs in Deep-Sea Mining Contract Areas,” Briefing Paper 02/2018, link. ↩

-

Katerina Teaiwa, Consuming Ocean Island: Stories of People and Phosphate from Banaba (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015), xvii. Gender and critical race theorist Mel Y. Chen might call this stratum “animacy hierarchy.” See Mel Y. Chen, Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012). ↩

-

Vicente M. Diaz, “No Land Is an ‘Island,’” Program in American Culture, University of Michigan, essay draft January 2, 2011. ↩

-

Epeli Hau‘ofa,“Our Sea of Islands,” in We Are the Ocean: Selected Works (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2008), 31. ↩

-

Matthew Spriggs, “Oceanic Connections in Deep Time,” pacificurrents 1, no. 1 (2009): 7–27. ↩

-

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s notion of planetarity can be useful here, as it transcends abstractions like globe or globalism for positions of specific situatedness. See Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013). See also poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant’s archipelagic thinking in Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997). ↩

-

Gender and cultural studies scholar Astrida Neimanis experiences what she calls “toxic love” in intimate debris, toxins affecting gendered fish morphologies, dumping of waste in the Windermere Basin in Southwestern Ontario. Astrida Neimanis, “Toxic Love,” in Sex Ecologies, ed. Stefanie Hessler (Trondheim, Cambridge, MA, and Linköping: Kunsthall Trondheim, MIT Press, and Seed Box, 2021). ↩

-

Anne Carson, “Water Margins: An Essay on Swimming by My Brother,” in Anne Carson, Plainwater (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995), 248–261, 254. ↩

-

Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 392. ↩

-

Sara Ahmed and Jackie Stacey suggest that skin lends itself to reflections “on inter-embodiment, on the mode of being-with and being-for, where one touches and is touched by others.” Sara Ahmed and Jackie Stacey, “Introduction: Dermographies,” in Thinking Through the Skin, ed. Sara Ahmed and Jackie Stacey (London and New York: Routledge, 2001), 1. ↩

-

Eva Hayward, “Schooled by Mackerels: Rachel Carson’s Curiosity,” IndyWeek (April 25, 2012), link. ↩

-

The phrase “endlessly obligated” is used by Sara Ahmed not in an ecological but in a social, ethical context. Sara Ahmed, Differences That Matter: Feminist Theory and Postmodernism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 63. ↩

-

See Karin Amimoto Ingersoll, Waves of Knowing: A Seascape Epistemology (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016). ↩

-

For instance, cartographer and writer Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina from 1539, the first map of the Nordic countries that depicts them surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, teems with sea monsters, issuing warnings to sailors but also luring explorers to distant lands. Chet Van Duzer, Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps (London: British Library, 2013). A counter example are Micronesian stick charts, mnemonic devices that are readable only through experience by the traveler situated within, not outside of, the map. ↩

-

Feminist scholar and activist for Indigenous rights Aileen Moreton-Robinson shows how the mistreatment of nature is sustained by the supposed superiority of the “rational” Western mind. Aileen Moreton-Robinson, “Towards a New Research Agenda? Foucault, Whiteness and Indigenous Sovereignty,” Journal of Sociology 42, no. 4 (2006): 383–395. ↩

-

For more on this paradox, see Philip E. Steinberg, The Social Construction of the Ocean (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011). ↩

-

Through the metaphor and methodology lent by the shoal, King also works to undo separations of Black traditions, discourses, and struggles as pertaining to the ocean as opposed to Indigeneity as being based in land. Tiffany Lethabo King, The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019). ↩

-

Teresia Teaiwa, ”Lo(o)sening the Edge,” Contemporary Pacific 13, no. 2 (Fall 2001), 343–357, 345. ↩

-

Sara Ahmed, “The Politics of Fear in the Making of Worlds,” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 16, no. 3 (2003): 377–398. ↩

-

Malcom Ferdinand, “Le refus de la possibilité d’habiter la Terre en presence d’un autre,” in Malcom Ferdinand, Une Écologie Décoloniale (Paris: Éditions du Séuil, 2019), 57, translation by the author. Thank you Anna Tje for introducing me to Ferdinand’s work. ↩

-

Ahmed, Differences That Matter, 63. ↩

-

Greta Gaard, “Toward a Queer Ecofeminism,” Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy 12, no. 1 (February 1997): 114–137, 115. ↩

-

Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde (Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 2007), 53–59. ↩

-

Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Dub: Finding Ceremony (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020), 13. ↩

-

T. Teaiwa, “Lo(o)sening the Edge,” 345. ↩

Stefanie Hessler is a curator, writer, and editor, the director of Kunsthall Trondheim in Norway, and the incoming director of the Swiss Institute in New York. Her work explores ecology and technology from intersectional feminist and queer perspectives and highlights the connections between environmental and social justice. She most recently co-curated the research-based transdisciplinary exhibition Sex Ecologies at Kunsthall Trondheim in collaboration with The Seed Box environmental humanities collaboratory, and edited the accompanying compendium on queer ecologies, sexuality, and care in more-than-human worlds (MIT Press, 2021).