Reset: Towards a New Commons, the most recent exhibition at New York’s Center for Architecture (CfA), opened at a moment when the idea of a unified public in the United States seems at best a relic of a bygone era. Between the backlash to the government’s response to COVID-19, the storming of the US Capitol, and the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade, divisions rather than commonalities dominate today’s structure of feeling in the United States.

In this context, curators Juliana Barton and Barry Bergdoll asked architects, planners, and professionals from relevant nonarchitectural fields (psychology, healthcare, social sciences) to explore what might draw communities together, and to envision how more united populations might be better served by the built environment. The resulting exhibition included not only designed responses to discrete architectural and urban challenges such as accessibility, gentrification, and disinvestment but also implicit demonstrations of the ways these social forces have begun to alter how architects and designers approach their professional roles in society. Just as the upper levels of government have become less proactive and more reactionary (think dueling executive orders and judicial stays in place of legislation and regulation), a comparable but more desirable shift has taken place in architecture, where the technocratic, singular architectural “solution” is increasingly being revealed as implausible (at best).

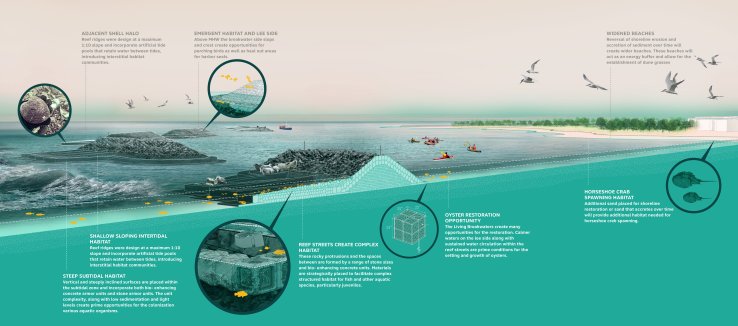

Speaking on her office’s Living Breakwaters project—a coastal reconstruction project (not included in the exhibition) off the coast of Staten Island—landscape architect Kate Orff notes that today, “there are no solutions, only choices.”1 In its context, this approach dismisses the notion of a onetime, all-encompassing “fix” for rising seas and more severe storm surges, instead engaging the local context to cultivate storm protection and coastal repair by nurturing the naturally occurring oyster beds that were pervasive in New York Harbor before European settlement.2 More broadly, a shift away from the single-size solution and toward contextual, sensitive, yet nonetheless inventive and dynamic, interventions presents an opportunity for architects to think big by zooming into already existing conditions. Reset’s teams of academics and practitioners showcase the professional fields of the built environment’s nascent shift away from top-down demonstration projects and form-based squabbles and toward meeting the design problems of the day on a more level footing with the most affected stakeholders.

Occupying all three floors of the CfA, Reset’s open call for proposals asked applicants to consider the potentials of Universal Design—design standards aimed at access for all3—to “envision new dynamics of living and community that challenge urban trends toward ever-increasing isolation” along three suggested typologies: living, healing, and gathering.4 Selected by co-curators Barton and Bergdoll, the four projects included explore a diverse range of imaginative frameworks for restorative, inclusive design in Oakland, Berkeley, Cincinnati, and New York City. While the prompt itself did not suggest a source of funding or a specific bureaucratic or legislative imperative that might spark the projects in the exhibition, nor ask teams to propose one, the winning projects do nonetheless engage either currently existing or historical political and social support networks—community groups, advocacy networks, neighborhood plans, and local residents—that might generate these accessible designs, helping to ground them in ongoing local efforts.

The ground level of the center was shared between Aging against the Machine, Block Party: From Independent Living to Disability Communalism, and a small selection of other built and speculative case studies, showcasing novel approaches to accessibility and cross-generational support. Neeraj Bhatia, Ignacio G. Galán, and Karen Kubey’s Aging against the Machine is located in Oakland, California, and focuses on urban-scale interventions reshaping the city for a multigenerational population, drawing from historical networks of communal care for the elderly that developed in the face of disinvestment and White flight in the 1970s. Aging moved quickly through time, with content shown along a monolithic angled plane in the center’s gallery, weaving oral accounts and photographic documentation of historic community-driven initiatives to support Oakland’s residents—regardless of age or ability—together with the team’s visions of how the needs of these populations might be met today.

In particular, Bhatia, Galán, and Kubey’s documentation of a simple community van program—Seniors Against a Fearful Environment (SAFE)—as a critical missing link between the elderly and the city (both for appointments as well as for socializing) is highly impactful. The Aging team moves from this simple observation to a visual study of how such a van-based system might work today as both a people-mover and mobile healthcare site. This reframing of mobility and mobility services, as foundational components of a wide-ranging set of design interventions (ramps, planted medians, stoops, and balconies) not only reconnects senior citizens with their city streetscape, it improves the public realm for all Oakland residents. The team illustrated these alterations in beautifully detailed dollhouse models—a strength of this project in particular—and stark but evocative collages. While the flashier aspects of this installation draw the eye, the team also included prosaic, off-the-shelf objects that have been either designed or modified for accessibility: doorknobs with special grips, dimensional lumber blocking that might anchor handrails or other mobility aids in place, and well-placed grab bars (in an alluring shade of pink), asserting these small objects as valuable components of their overall program.

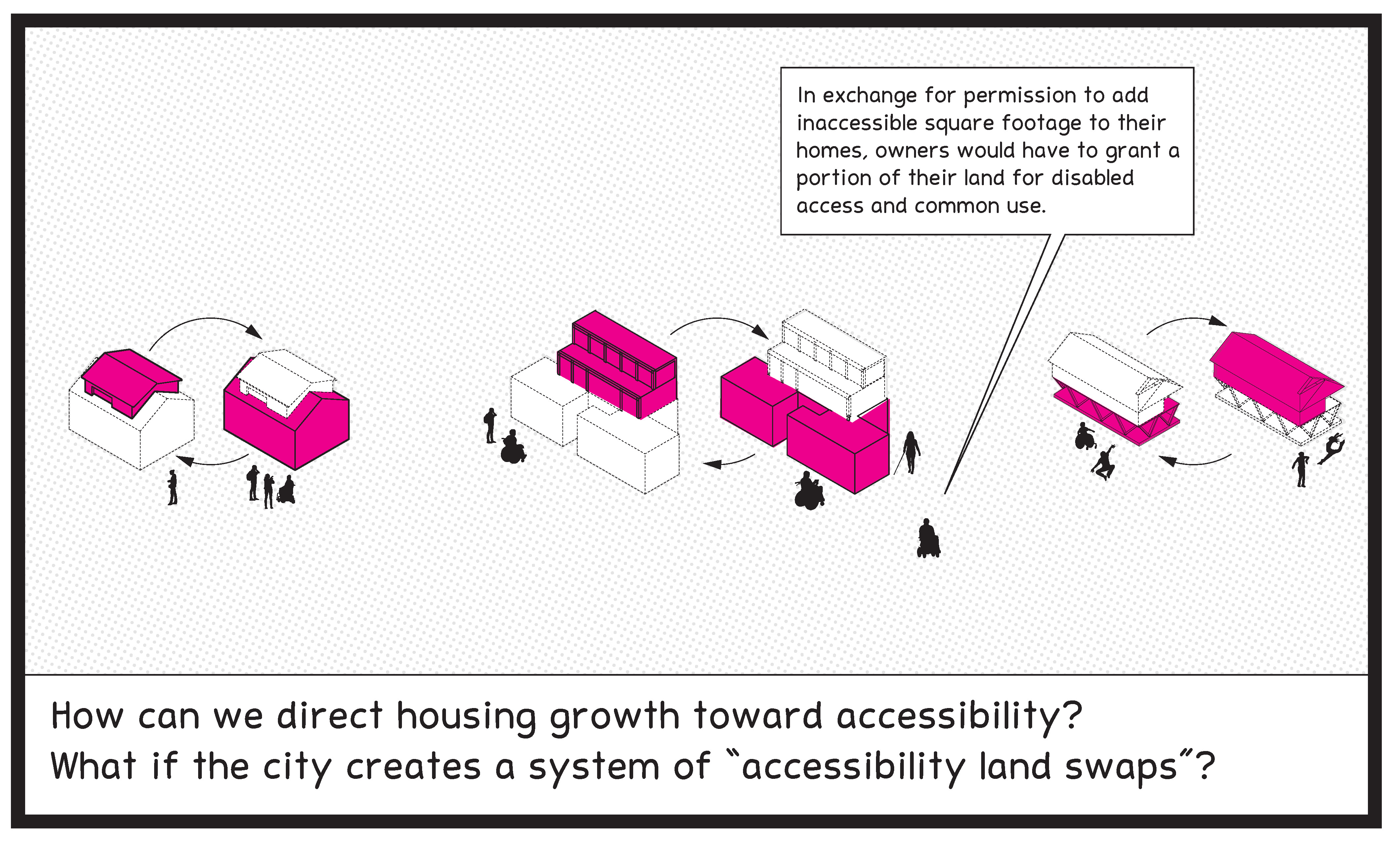

Block Party, shown across the room and sited in Berkeley, California, spent more time revealing the history of Berkeley as the birthplace of the “Independent Living Movement”—a grassroots program working to support autonomous living for people with disabilities.5 An immersive, large-scale graphic novel traces this activist legacy together with its policy successes (the Americans with Disabilities Act) and setbacks (the implementation of exclusionary single-family zoning), also featuring guerrilla acts of urban transformation (like using hammers to create curb cuts). The interface of two different kinds of “autonomy”—one focused on removing barriers between disabled populations and their cities, and the other devised primarily to protect real estate values by creating segregated single-family enclaves—generates an urgent and productive ground for Block Party’s interventions.

Noting the prevalence of low-slung single-family buildings in Berkeley along with the city’s recent abolition of single-family zoning, the team focused on exploiting modified zoning regulations to prioritize accessible connections between individual structures, using ramps, public elevators, shared patios, and backyards to weave together a new commons and generate new co-living arrangements. The team (led by Irene Cheng, David Gissen, and Brett Snyder) supplemented its historical and speculative drawings with a tabletop model of a proposed collective living block, featuring a neon pink snake of ramps, elevators, and connected yards and alleys. The overall effect was to reveal the ways relatively targeted changes to planning documents could transform a palimpsest of racist urban planning into a model for collective, abundant, and accessible housing—despite decades of urban policy and urban design to the contrary. Between Block Party and Aging, a refreshing dialectic emerged in the gallery: where the tools of “mundane” (vans, ramps) and even do-it-yourself design (grab bars, doorknobs) are included alongside more conventionally “architectural”-scale interventions (streetscape reconstructions, housing, public areas) as vital building blocks of a city where improvements geared toward access improve the urban experience for all residents.

Decolonizing Suburbia, by Architensions, Sharon Egretta Sutton, Parc Office, and Andrew Bruno, shared the basement floor with Re:Play: Reclaiming the Commons through Play. Focusing on Cincinnati, Ohio, Decolonizing Suburbia follows a path similar to those of the projects on the ground floor, using the Avondale neighborhood as a case study. Wall text told the history of the neighborhood, from its beginnings as a middle-income, predominantly White streetcar suburb to the arrival of a majority African-American population in the lead-up to World War II, and finally to Avondale’s financial decline during the era of White flight and its eventual declaration by city government officials as “blighted” in the 1950s. Beginning with Avondale’s community-led Quality of Life Plan of 2019, the team developed four distinct strategies with which to generate a supplemental tool kit fostering cooperation, interaction, and mutual assistance: Improving Safety, Making Connections, Sharing Success, and Improving Housing, illustrated throughout with highly detailed isometric drawings and renditions of modular components that begin to knit together existing housing, vacant lots, and public spaces. Many of the tactics here were akin to those deployed in Block Party and Aging against the Machine—testament, perhaps, to the pervasive, cascading ills of the United States's investment in detached homes as a default urban and suburban condition for much of the past century. The most architecture-forward of the teams in terms of both substance and representational decisions, the team behind Decolonizing Suburbia created an engrossing, thoughtful installation that rewarded close reading and long stays with the fine line drawings on the walls and in a minimal, peach study carrel occupying the middle of their gallery.

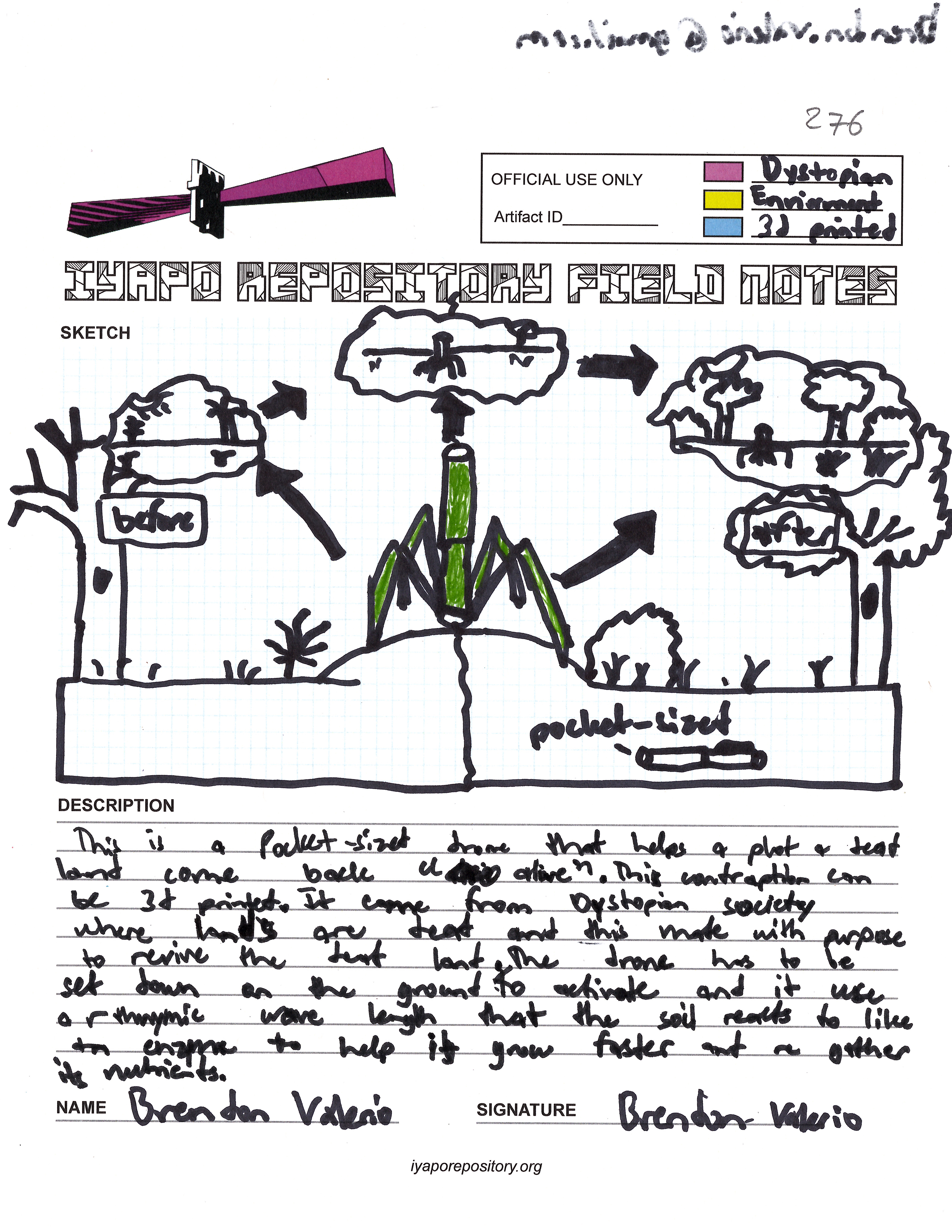

Re:Play, led by Deborah Gans, David Burney, and an interdisciplinary team of architects and New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) youth fellows, featured a thoughtful selection of projects at three NYCHA sites in East Harlem: the Thomas Jefferson Houses, the James Weldon Johnson Houses, and the Robert F. Wagner Houses. Most of the material originates from long-term collaboration with the team’s fellows and was displayed in a niche allowing visitors to stand surrounded on all four sides by large-scale maps, videos, collages, and models. The youth fellows’ work includes recorded testimonials of their lives in NYCHA properties, speculative collages showing suggested improvements, and physical models of their responses to the Field Notes from the Future project led by the Iyapo Repository (an art resource library “created to affirm and project the future of people of African descent” through both digital media and physical objects).6 The resulting collages are vibrant and clear, with a dexterity drawn from years of experience—vibrant playgrounds, acrobatic shade structures, and colorful paved pathways overtaking the usual concrete and grass plots between brick towers. The accompanying imagery avoids cynicism (as one might expect following recent reports of NYCHA’s underfunding and mismanagement7); rather, documentary films portrayed the campuses as incubators and showcases for cultures of the African diaspora in New York, while other testimonials from residents spoke to both the challenges NYCHA’s urbanism creates as well as the intense, clear-eyed optimism of its residents and the potentials of allowing them to direct the agency’s future.

The teams (especially on the first floor) seemed to delight in illustrating the “nonarchitectural” aspects of their proposals. A speaker hung conspicuously above Block Party’s model played interviews with disability justice advocates, while the aforementioned doorknobs and handrails were prominently displayed among Aging’s photographic documentation of community-based social service groups. Similarly, Re:Play faithfully foregrounded the visions and observations of its youth partners. Taken in total, the strength of the exhibition was each team’s direct engagement with community stakeholders or activists, and the foregrounding of their stories as critical justifications for design responses. It is no coincidence that many of the interventions on display began and ended with policy or grassroots mobilization, placing design downstream from the levers of power that might shift a given city’s hard and soft infrastructures.

Here the implicit message of the exhibition’s call for proposals was on display: it does not take a degree in a design field to notice the signs of civic infrastructure funding shortfalls or repair backlogs; nor is one required to advocate for concrete measures to address discrimination or provide direct services to overlooked communities. In partnering designers with these local experts and non−design professionals, Reset’s design proposals operate in a productive zone between the material, everyday needs of specific sites or interest groups and the freewheeling world of architectural speculation—proving that one does not need to disregard real-world constraints to let the architectural imagination run wild.

But this perspective isn’t yet shared widely. One need only look at recent design headlines to see the inverse of Reset, where architecture is used in service of a different approach to problem solving. The proposed city The Line, part of Saudi Arabia's Neom megaproject (announced concurrently to Reset’s run), has harnessed the trope of a linear city, running from the Red Sea into a seemingly inhospitable desert, supporting millions of residents among a hallucinogenic jumble of plants and aquatic environments—what has been referred to as “essentially a monumental wall.”8 Gökçe Günel notes that marketing materials for Neom place the project within a lineage of historical wonders of the ancient Mediterranean, all of which (save the Pyramids of Giza) are long gone or may never have existed at all, as validation for Neom’s future, “projecting monumental grandeur onto an abstract future and disseminating these visions within a present in which they cannot be fully held accountable for their projections.”9

If Reset’s proposals speak to one kind of spatial politics, wherein specific, local communities working on a discrete set of transformative objectives generates visionary design, Neom’s politics are distinctly geopolitical and broad, yet nonetheless rendered in high-resolution, photo-real digital certainty. Gesturing toward mass climate migration, Neom envisions new residents relocating to The Line to avoid flooding and drought elsewhere in the world, and the eventual rise of a generation of citizens who have only ever known life within The Line’s walls. The Line emerges in parallel with Saudi Arabia’s transition away from fossil fuels, yet elides the fact that in order to fund The Line or any other aspect of Neom, the Kingdom will need to continue selling oil on the global market, contributing to the very climate events that will (theoretically) drive new residents to settle there in the first place.10 Held against the standard of Aging against the Machine or Re:Play, who The Line’s theoretical residents are, or what their preferred alternatives to obligatory migration might be, is conspicuously vague.

Beyond Neom, evidence of the top-down architectural project’s persistence abounds, with paper projects that architectural critic Kate Wagner terms “PR-chitecture”—“proposed projects, ideas, and innovations that generate a lot of hype and publicity and yet never materialize”—on the one hand, and the very real infrastructural projects undertaken by governments around the world on the other.11 In contrast to the specific stakeholders and communities set forth in Reset, these projects are either intentionally unclear about who they are built for or who will pay for them (think Bjarke Ingels’s floating Oceanix City for the United Nations12) or cloaked in nationalist rhetoric of an overly broad public good (Singapore’s territorial expansion through landfill, highway expansions or oil and gas pipelines in the United States).13 Viewed through the lens of the curators’ call in Reset, one cannot help but ask how these projects might define their “commons,” and how they might perpetuate the kind of heavy-handed development that much of Reset seeks to address and undo.

While thoroughly impressed and energized by the optimistic, detailed projects on display in the center, upon leaving the show I found my thoughts turning to a persistent, and persistently depressing, question: Why have none of these common-sense interventions come to pass, in a meaningful way? Certainly, the pointed lack of silver bullet “solutionism” in the exhibition was a welcome breath of fresh air, and fits with an emerging view among practitioners and in academic circles—found in the work of many of the exhibition teams’ individual contributors—that architecture is a critical tool of investigation, question-making, and highly targeted intervention rather than an apparatus that can resolve sweeping sociopolitical problems on its own. Reset found itself in conversation with events like the most recent iteration of the Chicago Architectural Biennial, which abandoned the gilded era trappings of the Loop’s Cultural Center for community-facing lots in Chicago’s West and South Sides; or, in an expanded framework, the writings of Kiel Moe and Jane Hutton, who focus their attention on the flow of materials to and from building sites as registers of sociopolitical changes larger than architecture; and the work of educators like Cruz Garcia and Nathalie Frankowski, whose anti-colonial pedagogy and research turns architectural visualization methods back onto the field to expose historical and active entanglements between architects and repressive, extractive politics.14 The projects in Reset positioned designers as merely a single cog in a much larger machine of urban development, content to push for diffuse, small-scale architectural changes as part of broad coalitions of activists and stakeholders advocating collectively for political change.

If the turn against solutionism holds, Reset provided proof positive that leaving the architectural prestige objects of yesteryear in the dustbin does not mean abandoning drawing, craft, or visual narrative. Through and through, the project teams identified ways to fabricate exquisite models, visionary drawings, and provocative arguments, using similar but slightly different tools to what might have been found in the center’s galleries a generation ago. A conspicuous lack of the blunt “master plan” abounded; teams focused instead on urban corridors, tool kits, or rendering informal networks through isometrics, collage perspectives, and illustrations—buttressed throughout with rigorous research and detailed analysis for those more interested in reading rather than listening or simply looking. Shifting the goalposts of what “counts” as an architectural project is of critical importance, and is being embraced by the leading lights of the industry, from SCAPE’s Living Breakwaters to Pritzker Prize−winners Lacaton & Vassal’s “never demolish” ethos.15 The ennobling of simple objects like accessible door hardware or direct acts of community-building such as removing garden fences expands this lineage, not just meeting the letter of the law for access but leveraging these legal baselines to improve quality of life throughout entire neighborhoods.

These new paradigms of building also raise questions about the role of architecture’s professional association, the American Institute of Architects (AIA), whose New York chapter shares office space with the galleries that housed Reset. How can the profession of architecture confront the shifts in practice, fee structures, and labor that would be necessary to produce a world where renovation comes before demolition, where public and political reconstruction projects are favored over the desires of private clients? Architecture as an industry faces a similar reckoning as the cities explored in Reset: one where the problems and impacts are clear, yet straightforward solutions appear in short supply. The recent (incremental) successes in unionizing, both in academia16 and more recently in practice,17 speak to the erosion of office cultures, of burnout and long hours; the emergence of pro bono architectural collectives during the COVID-19 pandemic highlights the desire within the profession to steer practice toward direct engagement with the communities it serves.18

The CfA’s stated goals are to expose laypeople and other professionals to the potentials of working with architects.19 In that regard, the Reset teams have done a thorough job of reversing this dynamic and establishing the possibilities of bringing architects to communities with established needs and community-defined goals. One wonders if the center’s roommates, the AIA, have taken notice. The national AIA has spent much of the last six years “behind the eight ball,” chasing current events to align its positions with the realities of the contemporary political climate and its trickle-down effects on architects: from a tone-deaf pledge to work with former president Donald Trump after his election in 201620 to a belated ban on designing sites of torture or execution,21 a proactive vision of what architects should be doing remains elusive in AIA materials. Reset should be a wake-up call to the AIA that merely maintaining the status quo of the architecture profession—that is, advocating for infrastructure investment and more opportunities for architectural employment regardless of the party in power—does not adequately meet the contemporary moment. A more forward-looking, visionary understanding of what architecture could be and do—toward justice and equity in the built environment—is required.

Finally, within this framework of shifting professional standards and operational ethics, one cannot help but wonder what Reset says about another wicked problem facing the built environment today: climate change. Bergdoll and Barton’s call limits the scope of the exhibition to inclusive design and the more-than-worthy challenge of undoing decades of racist and ableist discrimination in US cities; and yet, there is no explicit mention in the curatorial statement of how the emerging climate crisis might compound—or already is affecting—the challenges disadvantaged communities face today, and the effects of climate change are largely referred to obliquely in the galleries. One hopes this is simply an editorial choice by the teams involved and not a tacit assumption that the strategic, collaborative design ethos on display in the galleries cannot be applied to something as cross-cutting as climate change.

At a time when the pressures of changing climates have already placed a large strain on the world’s cities—especially in the context of the US, where much of the obligation for care already rests with the individual citizen—it’s easy to assume the world will fall into an individualistic, survivalist, postapocalyptic mode. Reset provided a heartening alternative narrative, one whose lessons and discoveries are easy to translate to other spheres of collective action. After all, if the actual residents of Oakland, Berkeley, Cincinnati, and New York City can easily and expediently identify long-standing issues of access and security in their own homes, perhaps a new role for architects and design professionals will be as coordinators, facilitators, and record-keepers in support of our neighbors, uplifting and promoting the necessary work to bring about collective improvements in our public realm, looking both backward to redress historical wrongs and forward to envision a future truly held in common.

-

Quoted in Ariel Rubissow Okamoto, “Bi-Coastal Experiment with Oysters and Infrastructure,” KneeDeep Times, September 29, 2021, link. ↩

-

National Disability Authority, “What Is Universal Design?” link. Aimi Hamraie’s recent book Building Access: Universal Design and the Politics of Accessibility (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017) provides a pointed critique of these standards; when we say “design for all,” who defines “all”? And how can we assess the tools used to provide this access? For a recent example of these questions applied to contemporary construction, refer to the saga of the quasi-accessibility of Steven Holl’s Hunters Point Library, which met the letter of the law for accessibility by creating a second-class set of amenities for the disabled or those with strollers, in effect putting the most striking elements of the library off-limits for anyone unable to use stairs. See Leilah Stone, “Hunters Point Library Is Being Sued over ADA Violations,” Architect’s Newspaper, November 26, 2019, link. ↩

-

For more information on the Independent Living Movement, See Ignacio G. Galán, "Notes on Crip Camp," Avery Review 45, link. ↩

-

See Cindy Rodriguez, “NYCHA Falsifies Lead Documents, City Investigators Find,” WNYC, November 14, 2017, link; Luis Ferré-Sadurní, “‘Lighting Money on Fire’ as Mold and Rats Persist in New York Public Housing,” New York Times, July 26, 2019, link; and Gloria Oladipo, “Toxic Arsenic Levels Make Tap Water Unsafe for Thousands in New York City,” Guardian, September 6, 2022, link. ↩

-

Gökçe Günel, “New Wonders for the World,” e-Flux, September 2022, link. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Günel, “New Wonders for the World.” ↩

-

Kate Wagner, “No, PR-chitecture Won’t Save Us from the Pandemic,” Architect’s Newspaper, June 12, 2020, link. ↩

-

Eleanor Gibson, “BIG Unveils Oceanix City Concept for Floating Villages That Can Withstand Hurricanes,” Dezeen, April 4, 2019, link ↩

-

Galen Pardee, “Dunescape Urbanism; Or, The Stockpiles of Sand Geopolitics,” Thresholds 49 (April 2021): 89–94; Lisa Friedman, “Standing Rock Sioux Tribe Wins a Victory in Dakota Access Pipeline Case,” New York Times, March 25, 2020, link. ↩

-

See “The Available City,” link; Kiel Moe, Empire, State, & Building (Barcelona: Actar Publishers, 2017), and Jane Hutton, Reciprocal Landscapes: Stories of Material Movements (London: Routledge, 2019). See also “Loudreaders,” WAI Architecture Thinktank, link. ↩

-

See Eric Klinenberg, “The Seas Are Rising. Could Oysters Help?” New Yorker, August 2, 2021, link; see also Oliver Wainwright, “ ‘Sometimes the Answer Is to Do Nothing’: Unflashy French Duo Take Architecture’s Top Prize,” Guardian, March 16, 2021, link. ↩

-

Elaine Velie, “Non-Tenured Faculty at Chicago’s School of the Art Institute Push to Unionize,” Hyperallergic, May 11, 2022, link. ↩

-

Noam Scheiber, “Architects at a New York Firm Form the Industry’s Only Private-Sector Union,” New York Times, September 1, 2022, link. ↩

-

See, for example, Design Advocates, link; and Assembly for Chinatown from the office A+A+A in collaboration with Think!Chinatown, link. ↩

-

The Architect’s Newspaper Editors, “AIA Pledges to Work with Donald Trump, Membership Recoils,” Architect’s Newspaper, November 11, 2016, link. ↩

-

Martin C. Pedersen, “Why the AIA Finally Decided to Alter Its Code of Ethics on Prison Design,” CommonEdge, December 28, 2020, link. ↩

Galen Pardee directs the design and research studio Drawing Agency. He received a BA from Brandeis University and an MArch from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, where he currently teaches in the MArch program. Drawing Agency explores dimensions of architectural advocacy, material economy, adaptive reuse, and expanded practice through writing, exhibitions, and built design commissions.