Ruth Wilson Gilmore has given scholars, organizers, and students of radical history (and those of us who’ve lived the many formations of those experiences) so many gifts in the form of teach-ins, popular publications, interviews, strategy sessions, and long-form texts. Each gift is an offering and an invitation to consider, more fully, the dire situation racial-carceral capitalism has wrought upon us, and also the hope and revolutionary ammunition we hold within us to collectively envision and practice abolition. Abolition Geography: Essays Toward Liberation (Verso, 2022), and especially the section on which I’ll be focusing my review, “Part IV: Organizing for Abolition,” which includes chapters 16 through 20, is only the latest generous and supportive gift from Gilmore to liberation-minded abolitionist movements. This gift seems to be written as a call, an invitation to act and do, and given this approach, I’ll reflect on and give respective space to each chapter within this section.

While I have found hope, ways forward, and provocative challenges within all Gilmore’s works (Golden Gulag, her essays in Captive Genders, The Revolution Will Not Be Funded, and her Foreword in Rehearsals for Living, to name a few), Abolition Geography stirred something new within me. I want to deliberately name the affective theoretical work taking hold of me, as I’m feeling this shift, or rather, a new layered offering being developed and instantiated by Gilmore. This layered offering is spatial: it has a depth and interiority, but also feels expansive, stretching outward, pushing and demanding grounding—physical, tangible, even in feeling. This is a book that assumes the harrowing violent histories of racial capitalism, but presses beyond this insidious backdrop to anchor resistance-fueled theory-making. Her voice joins with the scaffolding of personal narratives, the detailing of movement history, and her political analysis. It’s precisely the convergence of these elements that creates a presentness that grounds us in realness, even as it beckons us toward imagination and envisioning place. Gilmore topographically situates personal/political experiences and hard, archival work alongside imagining horizons of abolitionist praxis and future(s). Dangerous and necessary, Abolition Geography reads like a love letter to comrades engaged in freedom work.1

As a queer, nonbinary femme and an abolitionist organizer (who happens to also find themselves in academia), thought-work and action, for me, are done through experimentation, hard lessons learned collectively, and constant knowledge sharing with others. Sitting with “Part IV: Organizing for Abolition” necessitated taking time and space to learn, test my gut feelings, and reflect on abolitionist strategies and tactics. There are case studies woven throughout this section that simultaneously work to illustrate Gilmore’s arguments, revisit turning-point moments in movement history, and show paths toward practicing what Gilmore introduces as abolition place-making2—abolition geographies.

Throughout this organizing-focused section, Gilmore does not shy away from directly addressing the shortcomings of reformers or the status quo’s enshrining of failed liberal ideologies, but she also commensurately takes to task leftists and radicals who aren’t taking seriously the charge to think critically beyond where we are in our current political landscape. This dual callout is beyond necessary, and welcome to my eyes, especially coming from a movement scholar, mentor, and organizer like Gilmore. Too often, reformist logics dominate our shared discourses and stunted understandings of possibility, even in leftist formations and intentionally radical spaces. Driven usually by nonprofit industrial interests and limited imaginations, people engaged in freedom work need to see such reformists called out and dragged through rigorous discourse in print to be reminded they are destined for the dustbin of history. If those so-called acceptable voices continue to determine the political trajectory of our debates and fill our minds, we stand very little chance. Rejecting the reformist co-optation of struggle (policy, language, action, thinking), embracing an abolitionist feminist3 politics, and finding ways to plug into doing freedom work with others is our only hope.

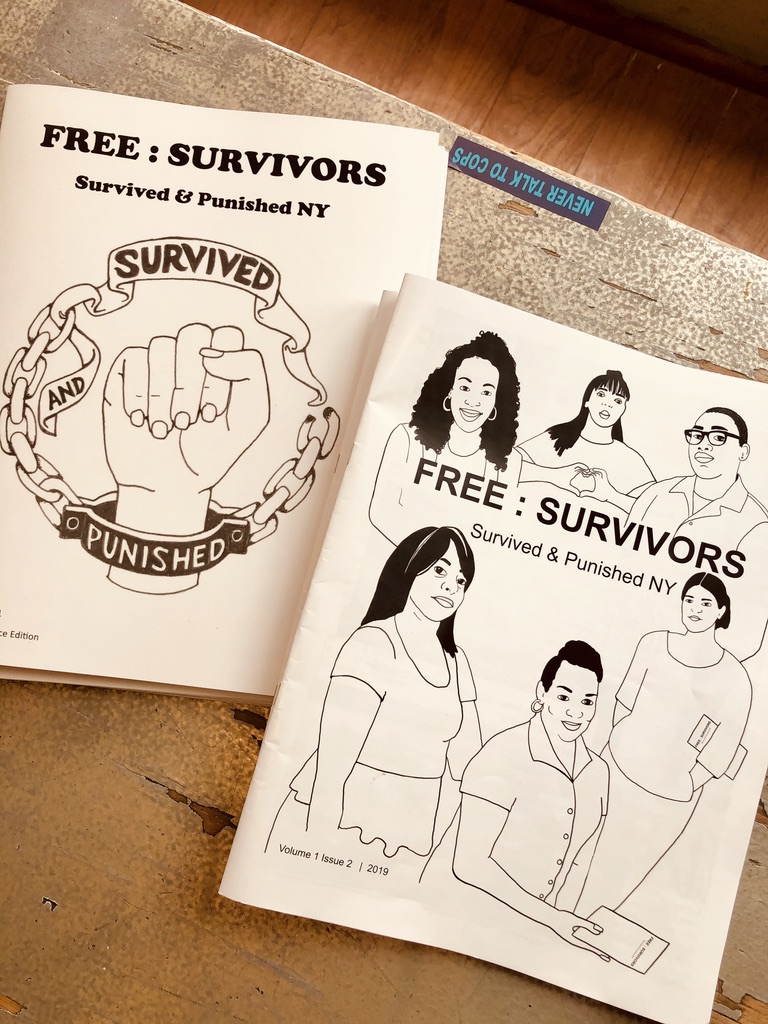

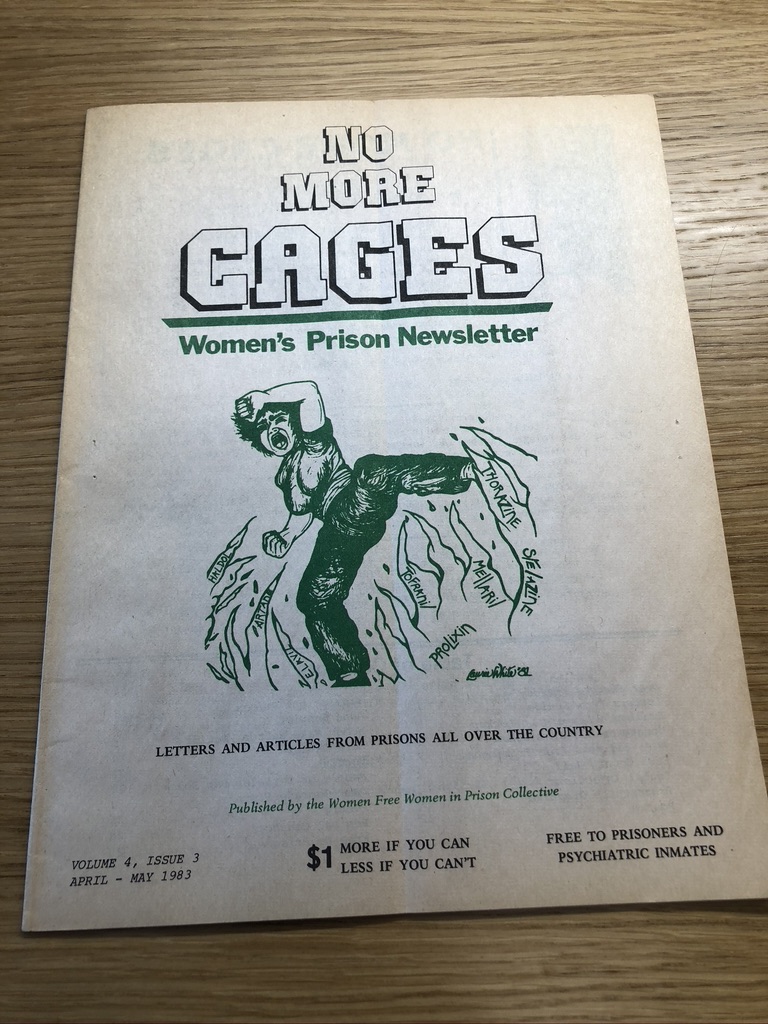

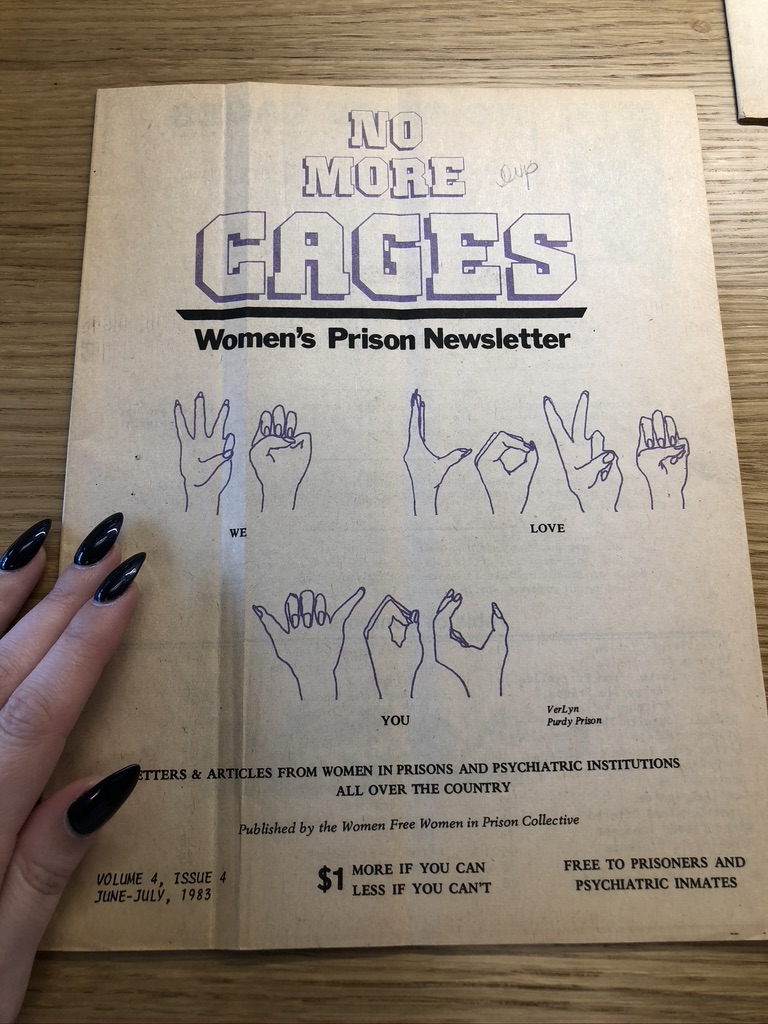

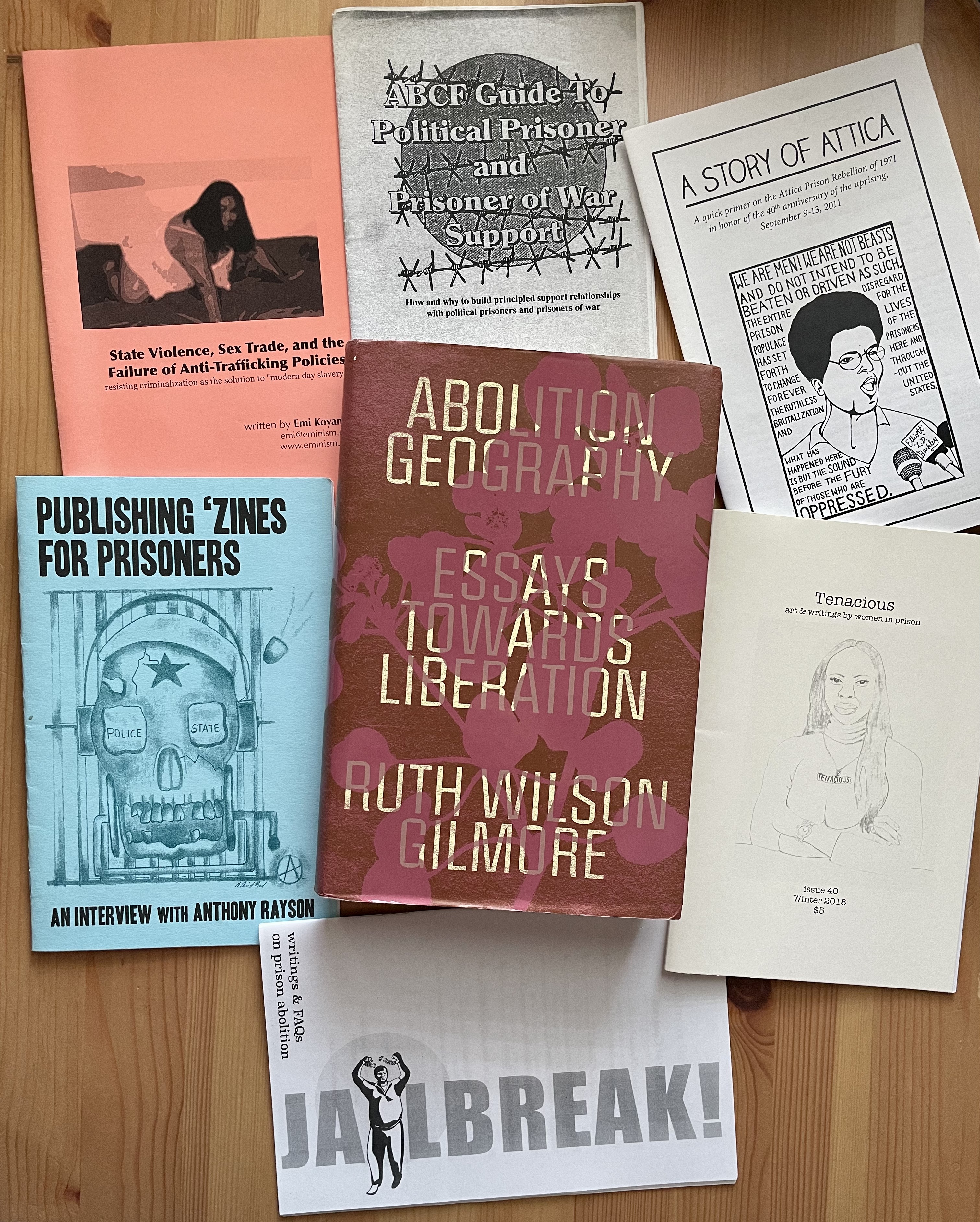

In this concluding section of her book, Gilmore draws examples from the anti-prison movement and other connected struggles from the late 1980s through the early 2000s. There is something here of unique importance, for Gilmore, in terms of the political and social landscape to speak to the conditions of today—and it certainly feels that way to me as well, as I reflect on what organizations and campaigns in my sixteen years of organizing, as well as the histories and models of political organizing from the 1970s through the 2010s, have looked like. As an example of these movement histories, I think immediately of how Emily Thuma’s All Our Trials4 dialogues with this reading. As a young organizer, I was mostly involved in intergenerational spaces against the death penalty, police brutality, and police rape—these spaces were co-built and filled with the experiences of those elders who were already seasoned organizers by the 1980s and 1990s. Working through this concluding section of Gilmore’s chapter, I thought about the inside/outside organizations that Thuma detailed, re-creating in my mind the covers of those prison newsletters Thuma cites, and walked over to my zine baskets and boxes to go through old anarchist and communist zines and survivor-made inside/outside newsletters about prisoner solidarity work. I reached for Tenacious: Art & Writings by Women in Prison (Law, 2018), Jailbreak! (Abolition Action, 2019), A Story of Attica (Project NIA, 2011), Publishing Zines for Prisoners (South Chicago ABC, 2015), ABCF Guide to Political Prisoner and Prisoner of War Support (ABCF, 1997), State Violence, Sex Trade, and the Failure of Anti-Trafficking Policies (Koyama, 2012), and for my notes on No More Cages: Women’s Prison Newsletter (Women Free Women in Prison Collective, 1983), issues that I documented extensively when my Survived & Punished NY Free: Survivors newsletter working group comrades and I visited the Barnard archives together the month before the Covid-19 pandemic first swept through our city and lives. I know I am not alone in reading like this—weaving constellations of teachers, experiences, and lessons together as I process and explore the theoretical work of a text. And due to this text’s density and complexity, Gilmore’s writing invites these reading practices.

Future-Thinking

In other words, if abolitionists are, first and foremost, committed to the possibility of full and rich lives for everybody, then that would mean that all kinds of distinctions and categorizations that divide us—innocent/guilty; documented/not; Black, white, Brown; citizen/not-citizen—would have to yield in favor of other things, like the right to water, the right to air, the right to the countryside, the right to the city, whatever these rights are.5

In keeping with Gilmore’s own anti-conclusion conclusion, I’ll begin near the close. Chapter 19, “Race, Capitalist Crisis, and Abolitionist Organizing,” consists of a conversational early 2010 interview between Gilmore and Jenna Loyd, “a feminist geographer documenting people’s freedom movements.”6 With questions and topics that range from reflecting on past movement organizing experiences to expansive thinking around what actually constitutes the prison industrial complex, Loyd orients her line of questioning to anchor Gilmore’s future-thinking discussions that speak to the utopian nature of abolition.

It opens with locating the start of Gilmore’s involvement with anti-prison organizing work and the motivations that led her to it, which then swiftly swells into discussions around the prison industrial complex—demonstrating Gilmore’s push and pull with the concept/term for some time. From here, Loyd directs questions toward the history of criminalization, the rise of class, and the history of capitalism, where Gilmore points us toward the violent extraction of labor and the detention of low-wage surplus labor that capitalism requires. Gilmore is also careful to remind us of the role of detention and class for those crossing borders for life and work. When it comes to questions connecting chattel slavery in the United States and prisons, Gilmore brings in Orlando Patterson’s analysis around “undifferentiated difference,”7 and from that asks the question, “What is it about people who have been criminalized that keeps them permanently, rather than temporarily (during an unfortunate period in their lives), in this enemy status?”8

By using Patterson’s “enemy” framework to explain the underlying contempt, fear, hatred, and animosity large swaths of our society feel toward those whose gender, race, and/or class position have put them in the category of “criminal,” Gilmore connects the legacy of chattel slavery to the current carceral geography of our world beyond linking inherited laws. The interview and conversation turn toward organizing many groups of people and connecting abolition with struggles for migrant justice. These conversation-moments reinforce Gilmore’s concepts in an incredibly approachable way (as they may appear with more complexity and density in other parts of her book). For instance, when Loyd asks her about how she conceives the process of organizing many different groups of people, Gilmore responds both casually and definitively: “When I think about organizing, I ask myself: What would people actually do?”9 It’s this unwavering real-talk and experience that fill you up as you read. As such, I suggest starting with this chapter to open up thinking through the entire concluding section.

Considering Space, Socially Reproductive Labor, and Resistance

The political geography of the state’s industrialized punishment systems determines the scale of everyday struggle.10

In Chapter 16, titled “You Have Dislodged a Boulder: Mothers and Prisoners in the Post-Keynesian California Landscape,” Gilmore introduces readers to an organization that sits at the center of how she thinks through carceral geographies and sites of resistance. Mothers ROC, or “Mothers Reclaiming Our Children (MROC), is a grassroots organization founded by Barbara Meredith and Francie Arbol in 1992. The MROC project took off in defense of Barbara Meredith’s son, an ex-gangster of the 1992 LA gang truce who had been arrested on false charges. Due to the state locking womens’ sons into prison for exaggerated offenses, Meredith and Arbol, along with other mothers whose sons had been subject to this crisis, spearheaded the MROC movement. The movement circulated throughout Los Angeles in hopes to reclaim the freedom of their wrongfully accused children.”11 As Gilmore offers readers an account of the organization’s actions, she also details the material and social conditions of their formation and early experiences of organizing by translating their “reproductive labor as primary caregiver into activism.”12 As she theorizes, she outlines Mothers ROC as a case study in the place-making work of abolition. I’m thinking of all the times I’ve named an organization as my “political home” or my “organizing home-space,” and though this isn’t exactly what Gilmore is saying here, I can feel a kinship between how we constitute new care-informed and challenging communities through joining and building campaigns and organizations, through caregiving, and through imagining the spaces we take up to matter beyond ourselves, and become worth fighting for. Invoking Gramsci, Gilmore characterizes Mothers ROC’s praxis as one that “renovates and makes critical already existing activities” of both action and analysis to build a movement.13 One of the more powerful reflections Gilmore shared was detailing how crisis (in the most capacious sense, capitalism, the state’s organized abandonment of Black and brown people, incarceration of loved ones, and more) was used as an opportunity instead of a constraint throughout organizing work during which members had to “switch among the many and sometimes conflicting roles required of caregivers, waged workers, and justice advocates.”14 This capacity to switch between many roles serves as the all too real “evidence of how people organize against their abandonment.”15 Later in this chapter, she expands our vocabulary around punishment systems and the role of racialized, but especially gendered, contractions within our brand of this late-stage capitalist society.16 Cue the affirming and fervent finger snaps.

Near the end of the chapter, Gilmore provokes with a haunting question (especially for experienced organizers): “Organizing is always constrained by recognition: How do people come to actively identify in and act through a group such that its collective end surpasses reification of characteristics (e.g., identity politics) or protection of a fixed set of interests (e.g., corporatist politics) and, instead, extends toward an evolving, purposeful social movement (e.g., class politics)?”17 This question is also a good example of the density and complexity that require a constellating reading practice. Here, as in many other moments in this section, constellating offers a way for us to hold our own experiences, Gilmore’s analyses, and radical histories alongside one another, connecting and building knowledge more fully. Perhaps one way people come to actively identify and organize regardless of identity-impact is through acknowledging and embracing the “everyday messiness”18 Gilmore describes within the “techniques of mothering that extend past limits of household, kinship, and neighborhood, past gender and racial divisions of social space to embrace political projects to reclaim children.”19 And, for these same people, to become “not petitioners but rather antagonists” toward the carceral state.20 Admittedly, this reader sees a host of limitations to the concepts of “mothering” and “motherhood.” I’d much rather have seen Gilmore draw upon other radical parenting and youth self-organizing and/or youth community worker frameworks or experiences to complicate the ways in which she saw and experienced Mothers ROC’s methods and organizing efforts extending past the nuclear family and the traditional socially reproduced models of caregiving that capitalism demands.

Gilmore complicates and extends Marx in incredibly relevant and helpful ways here, pointing to both the immense reach of incarceration and the equally enormous possibilities to undermine and abolish it (precisely because of how it unavoidably organizes those most affected against it)—“the material of political action in the folds of contradiction.”21

Unpacking this further: As an organizer, I’ve learned that we have to go beyond “meeting people where they are at” and directly create spaces that invite authentic and organic (meaning in-place, situated, connected) trust-building, venting, grieving, and celebration—embracing our and our comrades’ whole selves that we bring into the spaces we’re concretizing together. When diverse communities have opportunities to process trauma and pursue healing together in an intentional way, the political possibilities for self-organizing are limitless. Just as engaging in social movement organizing requires us to have layered, spatially diverse and robust approaches to our strategy and tactics, so too Gilmore layers and builds her arguments within this text. Abolition Geography reflects the necessity of these kinds of experiences, and Gilmore fills this textual space with livingness.

No One Forgotten, No One Disposable

Forgotten places, then, are both symptomatic of and intimately shaped by crisis.22

Chapter 17, titled “Forgotten Places and the Seeds of Grassroots Planning,” aims to, in Gilmore’s own words, “conceptualize the kinds of places where prisoners come from and where prisons are built as a single, though spatially discontinuous, abandoned region.”23 Here she spends considerable time introducing readers to the (radical leanings of the) discipline of geography, including theories and manifestations of “organized abandonment,”24 the definition of which draws upon the work of Marxist geographer David Harvey. Gilmore’s theorizing also broadens and hones in on Greenberg and Schneider’s designation of “marginal people on marginal lands.”25 This chapter and the ones following it emphasize the imperative for scholars to both practice and think in ways that make a difference, that embody radical politics.

In thinking deeper about place, Gilmore points us toward connecting urban and rural places in a fuller way, one that can wrestle with the challenges raised by drawing attention to the relationships between city and country.26 She asks us to consider: What about the “forgotten places that are absorbed into the gulag yet exceed them?”27 Gilmore employs the concept of desakota (Malay for "town-country"),28 a kind of modified blending that offers a way to think about city and country that embraces a “Third World” politics and analysis. In an extended note about the “Third World” as formation, Gilmore outlines myriad critiques against the nomenclature (the danger of a fascistic deployment of “threes” and the “bad dialectics” that can emerge from a “transcendental third”), but also details the powerful position such a framework has offered (what we could refer to as the “good dialectics” at work in seeing the third as a way of opening up prospects to revisit and view internationalist relationships).29 Utilizing this framework helps to situate rural and urban forgotten spaces alike. Gilmore reminds us, “Abandoned places are also planned concentrations or sinks of hazardous materials and destructive practices that are in turn sources of group differentiated vulnerabilities to premature death,”30 and that the use of desakota’s “syncretic”—or what Gilmore expands into “stretch,” “resonance,” and “resilience”—“compels us to think about problems and the theories and questions adequate to them.”31 These are ultimately methodological categories, helping the activist, the community member, and the theorist (obviously, Gilmore sees room for individuals to occupy all three subject positions) alike to formulate questions that meet the problems under consideration. In this sense, it is through stretch, resonance, and resilience that one can better interrogate the designation of forgotten spaces, in service of uplifting the fullness of the living, surviving, struggling, organizing realities of people in these places.

But what other work is done by formulating questions adequate to these social problems by employing the stretch, resonance, and resilience of Gilmore’s syncretic? To me, these are the essential questions and practices of political introspection organizers might ask themselves and their extended political community when undertaking any kind of collective campaign, building a new formation, or reconstituting an existing organization’s shared principles and paths forward in the work together. Stretch here means “enabl[ing] a question to reach further than the immediate object without bypassing its particularity,”32 or, in other words, finding the root of the surface question itself. Resonance “enables a question to support and model nonhierarchical collective action by producing a hum that... elicits responses that do not necessarily adhere to already-existing architectures of sense making.”33 Though Gilmore cites Ornette Coleman’s concept of harmolodics, Tina Campt’s haptic frequencies34 leapt to mind, and I urge readers to explore these tones, hums, and touch-frequencies alongside this chapter of Gilmore’s. Resilience, in this context, “enables a question to be flexible rather than brittle,”35 which is an important antidote to strategy stall-out or abrupt unforeseen changes in one’s campaigns, projects, or organizational work. Gilmore here reminds us that we must be prepared to act in our principles with a political dexterity that anticipates surprises (good or bad). By then applying these mantra-like expansive reformations of questioning, the rest of the chapter traces movement work case studies and sites of resistance from Gilmore’s present analytical moment, such as the work that coalesced around, contributed to, and was in solidarity with the California Prison Moratorium Project to illuminate how identities are shaped or altered through collective action and shared struggle.

Abandon Innocence, Adopt Abolition

The danger of this approach should be clear: by campaigning for the relatively innocent, advocates reinforce the assumption that others are relatively or absolutely guilty and do not deserve political or policy intervention.36

This quote, from chapter 18, “The Worrying State of the Anti-Prison Movement,” reminds me of attending a recent anti-death penalty rally and march in Austin, Texas, and being hit full-force with the overwhelming emphasis on innocence as a driving factor of demanding a moratorium on executions and abolishing the death penalty altogether.37

When we locate or fixate our politics on “crime” as opposed to, say, harm, reducing harm, and living in new, fuller ways with one another, we agree to the murderous state, and its armed agents’ terms. As Gilmore reminds us, we cannot limit our support to those perceived to have “relative innocence.” This convenient category is really a pit, a bottomless compromise fraught with deadly reactionary ideas and consequences. When we sell out segments of people who are criminalized, we sell out our politics and our collective futures, too. This selling out also means starting from the capitulating position of hierarchizing people who are experiencing extreme state violence, justifying the state-sanctioned punishments of some, so that a few may be “free.” For anyone reading Gilmore’s work, the fact that some people are criminalized who have not engaged in whatever the state says they have shouldn’t be up for debate. Of course there are people on death row who have not killed anyone! It is undeniably devastating to have a loved one incarcerated, let alone on death row. It is undeniably devastating to know the injustice of prosecutorial misconduct, contaminated or lost or tampered-with evidence, and to feel grief-stricken pain knowing a loved one should not be in that hell. But so too are these manifestations of carcerality devastating for everyone who has been punished by the state, regardless of their actions or behaviors. Using the facts of those specific cases in which an incarcerated person has been found or is presumed not to have committed the crimes of which they were accused, and turning those into a politics of “innocence” to be championed, which in reality leaves countless people behind in death houses, cannot be an option. For years I would respect when families wanted to center and focus on the “innocence” of their loved ones as those leading campaigns for their exoneration and release. And while I wouldn’t change my respect, I wish I’d had more abolitionist feminist texts like this one when I was a young organizer to bolster my feelings and politics. Understanding the rhetoric of innocence as a tactic when interfacing with the criminal legal system is one thing; bringing it into our hearts and movement spaces as a political framework is entirely another.

Gilmore also works to intellectually eviscerate the “new realists” who—in what she calls the “emerging bipartisan consensus”—exude the same stench. “However differently calibrated, the mainstream merger depends on shoddy analysis and historical amnesia—most notably the fact that bipartisan consensus built the prison-industrial complex (PIC).”38 This stench she describes them emitting is shared in common with their predecessors, the “law-and-order intellectuals” some forty years ago... a racist legacy parading as solution oriented that more than lingers today.

I have the misfortune, as do most grassroots organizers, of knowing too many of these “new realists”—too often have I had to hear their unimaginative and state-sycophantic cries: “But how can we legitimize violence?” “But what about the rapists and murderers?” “Don’t you think that’s a little extreme?” In my experience, these hindrances masquerading as allies or activists are often most concerned with ensconcing themselves in foundationally funded and/or nonprofit organizational careers, whose salaries belie an allegiance to self instead of affected communities. They have no desire to organize themselves out of existence; they remain content with the status quo so long as it allows for their privilege and comfort to be sustained. Gilmore writes about these foundations selling out the very organizations that were the backbone of their establishment and movement work.39 Gilmore underscores this, writing, “From the perspective of the deep-pocket new ‘new realists,’” the organizations that built the movement over the past two decades are profoundly unrealistic: their “politics are too radical, their grassroots constituents too unprofessional or too uneducated or too young or too formerly incarcerated, and their goals are too opposed to the status quo.”40 I'm thinking now of a research-based publication I worked on with a crew from Survived & Punished NY, “Preserving Punishment Power: A Grassroots Abolitionist Assessment of New York Reforms,”41 and just how apt the title we gave that report is. These “new realist” carceral capitulators, as Gilmore accounts of them (and as I have seen them in action), serve to preserve the most heinous of punishment-oriented systems in the name of change making.

Place-Making Freedom

Abolition geography starts from the homely premise that freedom is a place. Place-making is normal human activity: we figure out how to combine people, and land, and other resources with our social capacity to organize ourselves in a variety of ways, whether to stay put or to go wandering.42

Chapter 20, “Abolition Geography and the Problem of Innocence,” holds Gilmore’s directive for us to shift away from “prison industrial complex” as a framework, term, or concept and instead conceive of the vast networks, webs, industries, ideologies, and places of punishment as “carceral geographies.” It offers us a way “to renovate and make critical what abolition is all about.”43 This “making critical” is about the work, the space, and the stakes. The critical work of abolition regards activation through organizing—not simply becoming aware, giving money, sharing ideas, but putting those things into practice. The critical spaces concern being able to see just how far-reaching, and saturated, our terrains of organizing are—the geographies and spaces of them. And the critical stakes, of course, always reflect back on and further inform the visioning work on what we can build in the now, toward a horizon of a new world. She takes time and care to retrace the original intentions of the framework and term, locating its usefulness (at the time, and I would argue persistent usefulness despite Gilmore’s reservations) and explaining how and why it would serve us to complicate what we’re actually talking about, and to instead “spread out imaginative understanding of the system’s apparently boundless boundary-making.”44

This anti-conclusion conclusion is truly measured, imaginative, and pulls together the many threads running through the entire book. Using the concepts of Money, Abolition Geography, The Problem of Innocence, and an Infrastructure of Feeling as containers to underscore the connectivity of labor, exploitation, myths of criminality and safety, place, abandonment, and the paths toward possibilities of real change, this chapter is a beginning, a furthering, a lasting set of analyses.

Abolition as Our Horizon and Political Home

Abolition geography and the methods adequate to it (for making, finding, and understanding) elaborate the spatial—which is to say the human-environment processes—of Du Bois and Davis’s abolition democracy. Abolition geography is capacious (it isn’t only by, for, or about Black people) and specific (it’s a guide to action for both understanding and rethinking how we combine our labor with each other and the earth). Abolition geography takes feeling and agency to be constitutive of, no less than constrained by, structure. In other words, it’s a way of studying, and of doing political organizing, and of being in the world, and of worlding ourselves.45

A problem with this book, as I’ve experienced it (especially as a neurodivergent person), is that you have to highlight every single sentence because of the accounting, precision, and gravity of each as a vessel of thought toward the next, building in succession a cascade of deft argument and analysis. That being said, readers will not leave this text confused about methods to move forward; the expansiveness with which Gilmore writes about praxis and methodology consistently reminds the reader that her calls to “get organized” or “join an organization” are not meant lightly, or as asides.

These calls are central to the work, but also key are the kinds of organizations she champions. Explored through storytelling, each case study of a campaign or an organization helps us identify the kinds of spaces most likely to grow abolitionist politics and foster change. Gilmore also doesn’t discount new formations and the refashioning of existing ideas or groups; in fact, she explains how new formations can create new opportunities to tackle prevailing political problems.

Gilmore’s approach to language and the way she weaves theoretical concepts through storytelling doesn’t diminish her analysis. You can feel her belief that organizers, academics, and combinations thereof can and should grapple with, but more importantly use, this text in a variety of contexts. This is a text that will greatly benefit from collective reading with others. Study groups are not just for those people recognized as students within an institution; this book can and should incubate political education efforts in formal and informal organizations, in comrade reading circles, and among anyone alongside whom one is engaged in struggle. I say this largely because of the rigorous redirection of theory, complication of anti-prison movement histories, and the intensity of the language being developed by Gilmore—having a crew of comrades to work through this content together serves both the text and the reader. Abolitionist feminist texts, such as those mentioned above written by organizers, have a tendency to be more and do more than other books, especially other books that parrot anti-carceral movement(s)’ language, or attempt to profit off regurgitation or oversimplification of organizer-scholars’ ideas. Abolition Geography contains fire, grit, and hope as well—in one chapter she outlines the political landscape and actors telling a grassroots history, in another she draws upon such histories to bring lessons around strategy and analysis forward, and in still another she lays out precisely why we need to let go of outdated or less useful concepts to embrace the full extent of what’s at stake for collective freedom work. But what unifies this “geographical” monograph, and what puts it in fairly exclusive company, is the throughline of praxis-based, organizing-centered, and, for want of a better term, practical analysis that seeks to meet its heady problems with questions worthy of the seriousness and urgency of abolition.

-

Dangerous toward freedom work’s enemies in its anti-carceral political program and rigor, and necessary because of that fact. ↩

-

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Abolition Geography: Essays Towards Liberation (Brooklyn, NY: Verso, 2022), 7. ↩

-

See the following texts for an expansive and thorough accounting of “abolition feminism”: Alisa Bierria, Jakeya Caruthers, and Brooke Lober, Abolition Feminisms Vol. 2: Feminist Ruptures Against the Carceral State (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2022); Angela Davis et al., Abolition. Feminism. Now. (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2021); and Mariame Kaba, We Do This ’Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2021). ↩

-

Emily L. Thuma, All Our Trials: Prisons, Policing, and the Feminist Fight to End Violence (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2019). ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 468–469. ↩

-

See link; she’s also an associate professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Wisconsin–Madison; link. ↩

-

Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018). ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 463. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 465. ↩

-

And especially for the members of Mothers ROC. See Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 408. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 358. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 359. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 357. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 359; I recall standing up from my seat at a picnic table outside a local coffee shop and punching upward into the air after reading this passage. ↩

-

On the “punishment industry” as Fordist industrialized punishment, see Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 363. On “time-space punishment,” see Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 363-4: carceral systems and their agents are not at all concerned with even paying lip service or appearing to rehabilitate. Gilmore writes that “Racism alone does not, however, adequately explain for whom, and for what, the system works.” Of particular note here is the emphasis Gilmore places on the social reproductive labor and caregiving work of the majority of the members of Mothers ROC. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 395. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 364. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 408. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 406. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 407. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 412; the questions she raises on this page especially felt key: What does “better” even mean? ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 410. ↩

-

“What geography enables is the combination of an innate (if unevenly developed) interdisciplinarity with the field’s central mission to examine the interfaces of the earth’s multiple natural and social spatial forms.” Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 411. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 412. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 413–414. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 415. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 417. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 415n14. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 418. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 421. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 421. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 421. ↩

-

“Refocusing our attention on their sonic and haptic frequencies and on the grammar of black fugitivity and refusal that they enact reveals the expressiveness of quiet, the generative dimensions of stasis, and the quotidian reclamations of interiority, dignity, and refusal marshaled by black subjects in their persistent striving for futurity.” Tina Marie Campt, Listening to Images (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 11. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 422. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 452. ↩

-

Originally appeared on Twitter, in a thread, link / full text copy and pasted in succession here: “It was really good to see so many familiar faces at the 23rd annual Texas March to End the Death Penalty this afternoon. Getting to hug folks I haven’t seen in almost 10 years—wow. It was a bittersweet reunion of course... New families were there since last I marched whose loved ones are caged on Texas’ death row, elders of the movement have passed, comrades inside have been murdered by the state, families still fighting twenty years on, the rhetoric more focused on “innocence” than ever... There was a lot of joy in seeing people today, and a lot of pain. I attended for all the people on death row, for the people who have killed, for people who haven’t—for every person caged by the racist, cruel, anti-poor carceral state. I attended not only because I believe the death penalty should be abolished, but because I believe all systems of caging, punishment, and state brutality ought to be. Every last one of them. Love and care and rage to all the families who gathered on the steps of the murderous Texas capitol, to everyone who continues to write to and visit, and love our comrades on death row, to everyone expanding freedom work to *all* those inside. Abolition now. Free Them All.” ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 449. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 450–451. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 449–453. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 474–475. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 480. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 480. ↩

-

Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 491. ↩

Brit Schulte is an Art History PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin, a community organizer, and zine maker. They study everyday print objects, as well as sex working, queer, and trans* histories. Their current organizing efforts center criminalized survivors, prison/police abolition, and the destigmatization of sex work. Their writing may be found at The Funambulist, In These Times, Monthly Review, The Appeal, and Truthout.