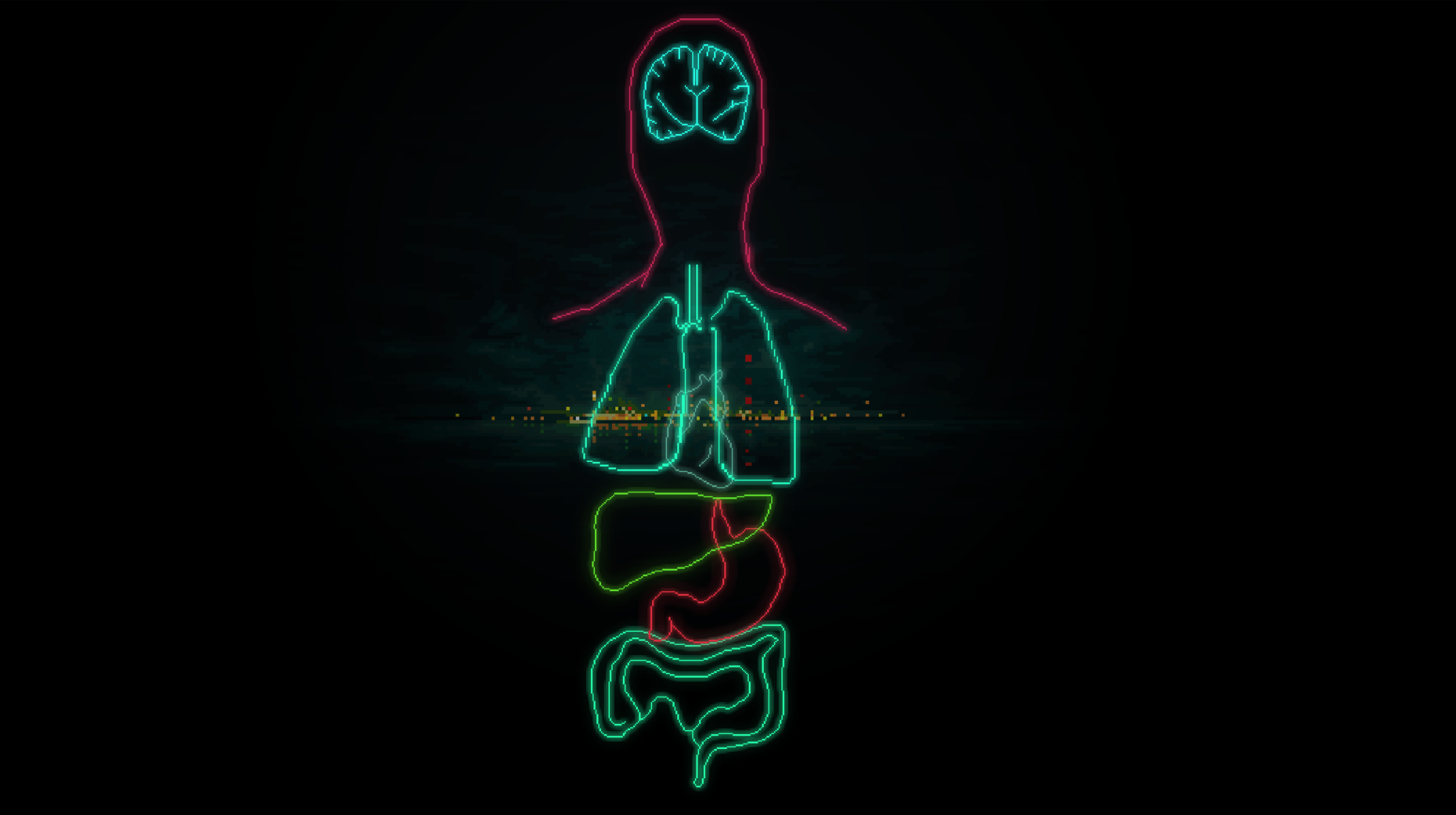

In the run-up to the 2022 release of the video game NORCO, the internet was flooded with strange images of lower Louisiana.1 Pixelated landscapes of bayous, elevated highways, and ubiquitous refinery infrastructure illuminated at night foretold a revival of the genre of point-and-click adventures made for PCs in the 1990s.2 But this release was going to be different. Gone were the wacky and humorous dystopias of Day of the Tentacle and Full Throttle, both released during the Clinton administration. The Louisiana in these images was dark in mood, unsettling, and uncanny. A neon outline of a cancer patient’s organs overlaid a view of a glowing drainage ditch—a vague reference to the fatal environment that would link the game’s characters. A chipped Madonna graced a front yard, enshrined in overgrowth veiling its eerie cybernetic innards. The Norco refinery looms large and menacing over these environments, and, when the game was finally published, it hummed along with the lo-fi soundtrack that accompanied the increasingly wild and violent storyline. NORCO, in image, sound, and story, would capture Louisiana and its people bearing up under climate change, fossil fuel exploitation, and centuries of racial capitalism. It would embrace the uneasiness, suffering, and joy of this place and fold them into a game that promised to be something more than entertainment.

Perhaps most compelling to us as historians is NORCO’s resistance to neat geographies and an easy American exceptionalism. The game’s setting, narrative, and characters are both in and of the United States, and, in some senses, it would be easy to transpose the game’s themes of capital, racism, religious fervor, and gothic decline into a distinctly “American” register. In one reading, NORCO would fit in well with other New Orleans cultural products captured as delightful if idiosyncratic fragments of “Americana.” Fetishizing the “South” as a romantic adjunct to mainstream American culture has a long history. White people in the United States have been eager to claim Louisiana as an Anglo domain (if wild, unruly, and therefore seductive) for two centuries. The perpetual US project of casting a net over the Mississippi Delta in an attempt to capture its human and chemical energy has produced a kind of default viewpoint: those from the US have been habituated to think of New Orleans as perched at their southern edge, the fin du monde where the swamps merge into the Gulf of Mexico. Generations of filibusteros dreamed imperial dreams from the US South—of capturing Cuba or Puerto Rico, of cutting canals through Nicaragua or Panama to shorten vast distances in the hemisphere, of finding the correct combination of engineering and military adventure that would finally convert the Gulf into “an American Sea.”3

These persistent geographic and mental orientations of those in the US looking southward to and from New Orleans make up a perspective that is absent from NORCO. Instead, the game’s labyrinthine story of capitalist extraction and the improvisational subcultures that work inside, beneath, and against its toxic landscapes is one that tumbles not down from its north but up from its south. Its geographies are built by pirates and runaways who inhabit and ignite the wake of watery currents, a world made as much in swamps and battures, in abandoned shopping malls and puppet theaters under interstate overpasses, as in corporate boardrooms and the chambers of city halls. These backwater places contain another structure that reframes the collective understanding of the US and the built environments of the Western Hemisphere: NORCO is a game about Louisiana’s place not in the United States but rather in the currents of the Caribbean Basin.

Poles

NORCO’s plots stretch over three acts, unfolding a family drama concerning daughter Kay, mother Catherine, and missing brother Blake, who all wind their way up and down the lower Mississippi River. The storylines are pulled toward an ambiguous end in two poles: a polyhumanistic party lurking in the dim Louisiana bayous and a halogen-lit plantation-petrochemical-AI complex situated on the banks of the river that stretches out to the coastline and beyond into the global flows of capital. While the plantation at the heart of the game—the Shield Oil refinery—masks the night sky behind flames and an endless sigh, the bayous hide maroons from this extractive world within their nearly mystical folds. But the two poles are related: to understand them not as dialectical opposites but rather as landscapes ambivalently twisted together, we must begin, as NORCO’s plot does, by playing as the character Kay.4

Kay is a young woman returning to the lower Mississippi River, where cancer has ravaged her mother’s body. She had tried disconnecting from the humming digital networks of her past and home, leaving to roam across the Southwest: “You threw your phone into the Rio Grande and joined the armies of the mesa.” Kay lived with fugitives, slept in nuclear bunker tunnels, fled while “the foot soldiers of a popup junta” battled in a burning Albuquerque. But her mother’s illness forces her to return. Kay wakes in her childhood bedroom in Norco, Louisiana, her mother already dead. Here too, things burn. Bands of pirates siphon oil and sabotage pieces of infrastructure, EMF waves distort television feeds, resident private investigators trade information for beer, and fenceline communities both resist and are overtaken by industrial infrastructure. As Kay, the player ventures around and outside her childhood house. Broad landscapes beckon exploration: industrial extraction, floods, and explosions have all left their own indelible marks—the “slow violence” has no visible end.5 Moving beyond the backyard garage, the convenience store, and the strip of state highway, the game’s first plot line continually arranges confrontations between Kay and a landscape that both creates and destroys.

As NORCO proceeds through its distended acts, the player jumps through time, between Kay’s timeline and a second plot, that of her mother, Catherine. The two narratives, set only months apart, twist together through places, people, and digital impressions of people that cross the timelines at differing speeds, both taking place during a night that is either in perpetual twilight or a suspended dawn. As Catherine, the player picks up the threads of her epic struggle with the oil company as her cancer enters its terminal stage. Mother and daughter both join and leave motley crews of punks and drunks in bars, old men in drainage ditches, lost boys in shopping malls, puppeteers under freeway overpasses, and mystics and alligators in bayous. As Catherine’s strange (and often funny, such as in a slowly unfolding side plot about a decidedly expired French Quarter hot dog) final odyssey unfolds in encounters with digitally copied human minds and giant birds, a question emerges for the player jumping back and forth between Catherine’s plot and that of her investigating daughter: Did Catherine plot against Shield Oil? Or did Shield Oil conspire against this lone, gravely ill woman living in a small ranch house in the shadows of its glowing complex of pipes, catalytic crackers, and burn-off towers? In the undercurrents of struggles against the Shield Oil petrochemical plantation—struggles against a kind of all-encompassing resource colonialism—what is to be found?

NORCO is the product of a yearslong collaboration of artists, digital musicians, dialogue editors, and programmers who form the collective Geography of Robots.6 For the most part, they remain puckishly anonymous, making use of pseudonyms and digital avatars. Their leader and the conceptual mastermind behind NORCO is a Louisianan who goes by the name “Yuts.” Yuts grew up in the shadow of Shell Oil’s hulking complex on the Mississippi River and has referred to the game as a kind of “technological diary” that uses all the media a modern video game affords to describe a place. There is more than proximity driving Yuts’s deep connection with the landscape. In a series of interviews with us, he described how being from this place prompted a continual (and unavoidable) reckoning with its complexity.7 He told us the story of how, when he was an infant, his parents lived near the petrochemical “fenceline”—a chain-link barrier separating the refinery from the neighborhood of modest working-class houses next door. One night, an explosion at the plant shattered the windows in their house. Finding the infant Yuts in his crib unharmed but covered in shards of glass, his parents packed up and temporarily moved across town, returning when company officials said it was safe. Yuts grew up within the refinery’s humming gravitational pull, and his parents still live in that house, despite the demonstrated menace next door.8

A city planner by training, Yuts described how after Hurricane Katrina he and a friend felt compelled to drive around destitute Louisiana, making recordings and paintings and projecting images onto the abandoned detritus that seemed to be the guts of people’s lives, ripped from their houses and spilled onto the streets. “Disasters like Katrina,” he told us, “are what drive history forward in many parts of the world, certainly in Louisiana.” Even so, there’s nothing linear or teleological about Geography of Robots’ method or gesture toward a philosophy of history. Witnessing space is akin to assembling a deep stochastic account of “environmental” history, complete with personalized grace notes of a common bayou argot, recognizable to those in the know, and signals that are like knowing winks. This sense of deep belonging drove Yuts further into the landscape after the hurricane. He described his response to disaster as a desire to “capture the stories and histories in the making of places that we dearly love.”9 History in this sense is both a personal process and a language exercise; it was from this compulsion that the beginnings of NORCO took shape.

Plots

In a 1971 article, the Jamaican poet, playwright, historian, and theorist Sylvia Wynter described a series of novels written from and about the Caribbean.10 For Wynter (and other critical and postcolonial thinkers), the genre of the novel was a quintessential European Enlightenment form of art—an extension of an increasingly ubiquitous market economy and an expression of daily life in an individualistic society. But she also suggested that the form, while a product of the market, nonetheless allowed other possibilities for plots that subvert and contest, that are both in and against the world. In Wynter’s thinking, two archetypical landscapes figure as conceptual anchors at the poles of sinking empires: the plantation and the plot. The plantation locates labor discipline and social organization in the landscape at the base of capitalism: sugar, coffee, and cotton’s ubiquity in the gears of capitalism made the case for the patchwork of work camps blanketing the Antilles as having central, global significance for humanity. The plot was the humble lot in the margins and cracks of the larger enterprise where the enslaved woman not only scratched out sustenance but also made community and kin. It is from this locus that counternarratives to the plantation are “plotted.” In using these two landscapes (in an archipelago where land is precious, no less), Wynter set up a juxtaposition between systems driven by the totalizing market toward exchange-value, and those shaped by human resistance and the provision of life. The modern Caribbean, she said, was made between plantation and plot: “two poles which originate in a single historical process” that are caught in an endlessly repeating confrontation.11 This dyad organizes the grand historical story of the Caribbean—the cauldron in which the alchemy of contemporary capitalism took place.

For us, it is the two poles of Wynter’s Caribbean that shape the geography of NORCO’s world. Shield Oil slouches on the Mississippi’s east bank upriver from New Orleans, just behind the levee, on the same naturally higher ground as the surrounding town of Norco. This was the ground of monocrop sugarcane plantations for more than two hundred years. A murkier geography stretches from the high land and runs into the bayous of Lake Pontchartrain. Its pathways are obscure, and getting lost can be lethal. This is the domain of hunters and loggers, truants and hermits, and generations of Black watermen. These swampy reaches are home to what historian J. T. Roane has called the “furtive geographies” of Black resistance and commons.12 In an act of both defiance and affirmation, “dark agoras” were made in saturated places outside planters’ interests, and the enslaved people of the region staked out relationships with their environment and with each other that were under their own control.13 These “commons” form an invisible infrastructure that feeds further imagination of resistance. In NORCO, it is from the swamp that counterplots are provisioned.

NORCO, however, plots in complex ways, taking advantage of a medium not yet available to Wynter’s authors of the Caribbean underbelly. Its pixeled refineries and bayous, and every bit of asphalt and oyster shell that travels in between, began as a series of paintings in acrylic on canvas. A real aha moment for Yuts came when he started threading these vibrating images together into a dialogic game. It was in this mode that the impressionistic world of the Louisiana bayou became occupiable, inhabitable, and accessible to interaction. Just as the novel form was for Wynter born of both plantation empires and plots against them, the point-and-click adventure video game is for Yuts and his collaborators a medium produced by its environment and, at the same time, a way to plot against it. “If it were only a novel,” Yuts said, “then you lose the specificity of how the region sounds and the small visual motifs.” And “if it were only a film,” he continued, “then something like the ‘mind map’ system, which dynamically illustrates the relationship between concepts and locales, wouldn’t be possible.”14 Made possible by the point-and-click medium, the mind map is a core orientation device that updates as Kay talks to more people, reads clues, or has a flood of memories triggered. Visually, it is a network of nodes signifying kinship ties, corporate entities, past catastrophes, and how they are all related to one another.

At various points in NORCO, Kay encounters what seems to be an endless party. She first meets a group of masqueraders in a renovated plantation house that reflects not only the long-lost Good Hope Plantation that once sat on the grounds of the real-life Shell Norco refinery but perhaps also Destrehan Plantation, a famous landmark still standing just down the river.15 They treat their decadent and dissipated drinking as a full-time occupation, confessing that they don’t know (or care) who their hosts are. When these masqueraders appear at the end of the game, detached witnesses to the end of the world, devoted to wine and resigned to all else, their aloof Greek chorus highlights how central techniques like the mind map are to what the game is trying to say. How does one focus when everyone else is simply trying to escape into bliss?

A striking notion in Wynter’s 1971 plot and plantation essay is the idea that an “ambivalence” about the value and meaning of the two poles of plot and plantation is “the distinguishing characteristic of the Caribbean response” to global racial empire.16 Even more striking is Wynter’s suggestion that this ambivalence is “at once the root cause of our alienation; and the possibility of our salvation.” As the game’s plot descends into a fever dream of competing eschatologies—how various characters come to believe in humanity’s ultimate destiny—Yuts’s most poignant statement on Louisiana emerges. The endless partiers drink on inflatable mattresses; the veterans of the forever war embrace their PTSD and plug into their night-vision goggles for one last sortie. The fanatics prepare a rocket that—they pray—will literally launch them out of the swamp. And Kay keeps it together to try to find her brother.

NORCO is a vote for baroque chaos at the end of the world, a feverish masquerade that can propagate new geographical and spatial interpretations. It becomes a machine for channeling the beloved chaos of Carnival, producing ways of looking at Louisiana, and the larger world, in the face of late-stage capitalism and unfolding climate change that are well out of Yuts’s hands. NORCO pulls the player into a believable world where culture settles into its distinct environments, where a momentary glimpse snaps players into moments of nostalgia and launches them into further contemplation of their own histories with landscapes. But then the game turns and asks the player what they will do when this weird world comes for them.

Ceremony

Writing a little over a decade after she laid out the polarities of plot and plantation, but still in the “lingering afterglow” of the “planetarily extended series of anti-colonial struggles” of the 1950s and 60s, Wynter rearticulated the hope for salvation as a reenactment of heresy, as a challenge to find another kind of life in the Caribbean.17 The long history of capitalism pulsing through the Caribbean traces back to the Mediterranean, where Wynter describes Renaissance humanism as the original heresy, replacing “Maximal God” with “Maximal Man.”18 The heresy proposed a narrow divinity, elevating the “mercantile upper bourgeoisie and newly landed gentry” to a kind of ultimate and universal power.19 This Mediterranean man eventually took on global dimensions, dispossessing the colonized by defining them as “inferior.” Back and forth across the Atlantic, the theory and politics built around this heresy were “humanly emancipatory” but also “humanly subjugating.”20 The challenge of the present, Wynter said, is to be heretical once again, to reenact that heresy of the Renaissance, but this time to emancipate the human rather than a singular, atomizing variation of Maximal Man.21 This is what she described as finding the “ceremony.”

From the position of Maximal Man orthodoxy, any straying from supposed progress in science, enlightenment, and market capitalization is to be met with hair-trigger retribution. In the batture, that liminal space between the levee and the rising and falling water’s edge, Kay finds a 2x4 cross supporting a remembrance spray-painted on plywood: “Here passed the brave freedom fighters of January XW11 whose cries of liberty echo through the generations.” In January 1811, the Black overseer Charles Deslondes led a revolt of hundreds of enslaved people against the plantation system, marching down the Mississippi, with New Orleans and full-on revolution as the goal.22 White militia drove the revolutionaries back to what is now Norco, killing many, and capturing, reenslaving, or executing the rest, their heads mounted on spikes lining the Mississippi’s banks to terrorize others into submission. These forms of heresy and revolt continue to percolate in the refinery’s present shadows. By this memorial to sugarcane heretics, Kay finds a modern-day reflection—Lucky, a shotgun-armed, pipeline-slashing bearded revolutionary who is forever eager to cross petrochemical fencelines and contrive other forms of industrial sabotage. A revolt against another form of Maximal Man begins to coalesce.

It is nineteenth-century plantation violence, both oppressive and disruptive, that NORCO’s twenty-first-century world reflects and repeats. Wynter writes that the Homo politicus of the Italian Renaissance and European Enlightenment was transformed in the fires of the nineteenth century’s industrial revolutions. Homo oeconomicus—the new incarnation of the same idea—has metastasized in the neoliberal present. This figure built the plantations and the textile plants they fed, leveraged this growing value into financial instruments that dug further furrows into the soil of the New and Old Worlds.23 Homo oeconomicus gave us bioracism and contemporary capitalism, dividing humanity according to biology and economic worth. This incarnation is responsible for the tense and despairing world of NORCO, a world in which some are selected and others “dysselected,” where supercharged industrial and financial output produced the cancer that destroyed Kay’s mother.24

Against this economic orthodoxy, Kay and Catherine’s search for a ceremony becomes a kind of heresy. Kay’s story winds up and down highways above New Orleans with the Shield Oil refinery burning in the background—a megalithic marker of supply chains that stretch far beyond her family house and its small town. Kay plots in the shadow of the plantation with Lucky, with a decommissioned humanoid robot, with a childhood teddy bear, with friends and enemies of her family. She is joined by a drunken, smart-mouthed PI named LeBlanc, with whom initial antagonism (and often hilarious riposte) shifts to bonds of deep care. Catherine’s story moves through the night to a puppet show under I-10, to French Quarter mystics hidden behind doors that open only to secret knocks, to shuttered and derelict shopping malls and an unlit stair tower, to warehouses inhabited by gigantic monstrous birds. With her traveling companion Dallas, Kay’s wariness also turns to profound trust and attachment, again born out of their being two marginal people staring down the idea that the rest of their lives will be equally marginal, but no less filled with struggle.

Just as NORCO begins with Kay’s plot, so does it end, moving from the refinery to its opposite pole in the bayous that border Lake Pontchartrain. The infrastructural traces of extraction are everywhere as she wades in. Wheeled furrows left from cypress logging scar the marshy ground and pipeline and interstate trenches stretch in unnaturally geometric lines across the murky landscape. As she dives under the scarred surface, Kay sees differently. Beneath the bayou waters, she develops a kind of vision necessary to see the ghost that still gives shape to these amorphous grounds. In a series of mystical experiences, her mind traces a shared past with the world, where her own personal history merges with geographic and hydrologic forces to create the present. Making her way to the carnival in the bayous, where people have floated in on boats and inflatable mattresses, she arrives at a place where competing eschatological visions collide. Under a sky still on fire with perpetual twilight, something else is being imagined as people try to find another kind of human, another kind of ceremony, in the “secretive history” of a plot not yet complete.25

Belly

It is this heretical geographic imaginary that makes the case for NORCO being more a work of Caribbean art than a piece of “Americana.” In A Common Wind, the historian Julius Scott fundamentally challenges the notion that the space of the Caribbean could be thought of as anything other than the networks of social ties and information about liberation that spread among the dispossessed of the entire basin.26 Unharnessed and un-suppressable, like wind, the polyglot and wildly organic culture of the oppressed economic base of the region that blasts through national and linguistic boundaries is what the historian has to follow. To us, thinking of NORCO within self-contained historiographical debates over the US South and its place in the larger nation would deny the twists and turns of revolutionary history that pulls Louisiana further toward its archipelagic south.

Depicting built environmental histories of capitalism involves a series of choices about plots. One decision is to write from the self-narrating monoliths of nation-states and transnational corporations. The Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico are places intimately linked to these trans-imperial and transnational behemoths. Similarly, we could narrate the built environmental history of this watery cauldron as one of hegemony. The empires have fallen, but their looming carcasses remain, posing an easy frame for any writer to use. But the history of the Caribbean basin can push us toward a different decision. Consider the underside, what the Martinican writer and poet Édouard Glissant calls the “belly” (and the “abyss”).27 Glissant, in a description of the belly of the slave ship as one of the several abysses that constitute the Middle Passage, frames a world that, no matter the ultimate form of a superstructure of extraction, has a belly filled with life and death. Every oil rig has its cluster of very real human hopes and fears in its orbit. Every underpass has its own accumulated miseries. Unflinchingly accepting and investigating these bellies is to the historian Walter Johnson the only way to avoid writing history as “therapy.” What good is returning an enslaved woman’s “voice” if we do not also see the very real structures of her life, if we do not see her “longing and hope and sadness and anger” in “historical terms”?28 To us, writing from the refinery’s belly—a giant industrial belly intertwined with Catherine’s own belly that struggles, and fails, to flush the malignant effects of its cancerous environment—is the only way to understand the systemic effects that pin down a place and force permutations of buckling down, resistance, or just flesh-and-blood life on the margins of the refinery’s high ground.29

NORCO critiques oil capital, poverty, despair, and environmental disruption along the lines of thought that already enlace it. The game prompts us to think about dispossession and injustice in relation to possible resistance. Its very existence is a subtle narrative of revolution. To regard the Gulf of Mexico from the US nation-state almost guarantees that we will never, as Wynter challenges, find a path of collective and ecumenical human liberation.30 That is, if we narrate the Gulf of Mexico from the North—as a quintessentially “American” (i.e., US-defined) sea—without also narrating from the South—as part of the revolutionary winds of the Caribbean Basin—we will not be able to see the heretics in this supposedly rationalized, enlightened world of transnational racial capital.31

As an architectural or environmental history, NORCO presents an undeniably alluring method by placing characters in their “settings.” The characters hang out in parking lots late at night, watch TV in their garages, lurk in the batture, sit in their trailers in the pitch dark. These are not high “Architectural” occupations of space, nor are they immediately apparent when we think about program or function. Reminding us of Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker’s study of the Atlantic working class, there’s something crucial to occupying this strange and foreign world in the undersides of capitalism.32 Like the “many-headed Hydra” of stranger-than-fiction characters that Linebaugh and Rediker have spent their careers trying to hear and understand, NORCO points to the unapparent form of the rough beast of this environment as essential to understanding the human import of events.

Thirty years after the original publication in 1984, Sylvia Wynter revisited her ideas about finding the ceremony and concluded that the heresy she sought remained incomplete.33 Recently she proposed completing that unfinished heresy by thinking through not atomized, Enlightenment man, but rather a collective and ecumenical type of human. This ecumenical human, this “we,” Wynter suggests, can only truly be discovered in what Frantz Fanon called a “gaze from below.”34 The humility entailed by the historian taking the position of the wretched has become the moral charge of doing history in the post-colonial world. Indeed, for Linebaugh and Rediker, “history from below” is, as a method, the only way to do the inherently political work of history in a righteous way.35

At points in NORCO, the player’s gaze is literally from below the muddy, watery depths of bayous, from below the detritus of extraction, and through the apparent despair of history tending toward decay. NORCO sees the distributed lives of people doing their thing as the, in the end, ungovernable refuge of life in Louisiana. What would it take to write architectural history from down here? What would it look like to write about architecture only through people “doing their thing”? What if we wrote from a different type of human, one not preoccupied with humanism but instead consumed with the ambivalence of living on a dying planet? What if we gave up on the Renaissance, disavowed our inheritance, chose a new mind map, redemption be damned? For one, it would likely mean freedom to interpret objects and systems like refinery complexes and mental maps of swamp fishers as intricacies as tightly symbolic and tectonic as any baroque church. Beyond this liberation of subject, it also might afford new tools to write histories into the structures of class and race that have poisoned the Western Hemisphere since Columbus. The Caribbean basin is a cauldron of extraction, misery, subjugation. It is a hugely capitalized, militarized, controlled space and has been for over five hundred years. And yet, it is not abject. The people of the Caribbean have always resisted total domination and flourished creatively in spite of the rise and fall of empires, bursting through the weaknesses of any net of control imposed upon them. We want histories of those weak spots, of a belly architecture that cannot be contained.

Flood

NORCO is set in a variant of the present, not quite our world but also not something other than it. And because of this indeterminant present, it plays as a kind of improvisation somewhere between where we were and where we are not yet. It is a kind of art that produces uncertainty; we don’t know how it will resolve. This is one of the values of games, as C. L. R. James identified in his meditation on the anti- or extra-imperial possibilities of cricket in Trinidad.36 Similar to flamenco and jazz and improvisational traditions in other cultural forms, the game is creation played within and against its rules—a space of potential liberation. While cricket spanned the British imperial world, it had the potential to be played—to be plotted, we might say—in creative and unpredictable ways.37

Drawing connections between biblical Jewish priests and Rastafarian “redemptive-prophetic intellectuals,” Wynter argues that these creative narrative possibilities, these alternative plays and plots, are what makes humanity what it is.38 To find the ceremony, we have to narrate and re-narrate, to find ourselves as Homo narrans.39 We make ourselves in the stories we tell and believe, stories that are born both in the refinery’s belly and at the top of its flare stacks. Playing in NORCO’s indeterminant variant of the present, the past and the future vibrate as they stretch across Kay and Catherine’s plots by different narratives of faith. Some of these faiths—these cosmogonies that wind together the individual and the vast geographies that extend out around them—want a kind of new certainty. The Garretts, disillusioned young men who have become disciples of a proto-fascist Kenner John and his digital gospel the Apocryphon, appear for Catherine as employees of a closed mall, and reappear to Kay dressed as crusaders in a bayou desperately looking for an ark that can take them to a completely different world. But others, like Kay and Catherine themselves, find the stories of humanity in the world in front of them, fallen and imperfect as it is. For Yuts, narratives of aging prophets, prodigal daughters, and teenagers desperate for something to believe in not only tell us what lower Louisiana is, they also ask us who we want to be.

Standing in the front yard of her childhood home, the past and future quite literally flood into Kay’s present, stretching the timeline of her life across a river pulsing through waterlogged building materials. The first flood she remembers only in a haze; her mom rips out drenched carpeting and her grandfather tears at ruined Sheetrock. A second and third deluges follow. The house is gutted again and again, as the river continues to rise and the Louisiana ground continues to sink. A fourth flood is coming, a future past, a potential history, already embedded in Kay’s memory. This flood is accompanied by blackouts, levee breaches beyond repair, and a regional descent into piracy and hijacking launched from high places of last resort, the river’s natural levees. A long-running threat by the Atchafalaya River basin is finally delivered on: the Old River Control Structure, which since the mid-twentieth century has precariously prevented the Atchafalaya from capturing the Mississippi’s mighty power and volume, collapses, and the river changes course.40 The deep waters flowing past Norco become a shallow trickle. The house, like the rest of its world, disappears, abandoned by capital and the federal government.

As NORCO comes to an end, Kay stands on the balcony of the ark envisioned by others as a mode of otherworldly salvation, looking toward a refinery that continues to veil the stars. The coastline opens wide as plantation-petrochemical flows follow halogen light down the Mississippi and out with global streams of capital. She knows a fourth flood will come as both infrastructural poles—ark and refinery—implode. But in this moment, the bayous hide. As they fade away, they signal their role as places of refuge, as places of ceremony. Kay finds her kin and dives in.

-

On the genre of the point-and-click adventure game, see Anastasia Salter, What Is Your Quest? From Adventure Games to Interactive Books (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2014). ↩

-

See, among many, Michel Gobat, Empire by Invitation: William Walker and Manifest Destiny in Central America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018); S. E. Abert, Is a Ship Canal Practicable? Notes, Historical and Statistical, upon the Projected Routes for an Interoceanic Ship Canal between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans (Cincinnati: R. W. Carroll, 1872); Jack Davis, The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea (New York: W. W. Norton, 2017). ↩

-

We believe that NORCO is an example of what Ian Bogost has called “procedural rhetoric,” as are a huge number of other simulation games. “Procedural rhetoric,” writes Bogost, “is a general name for the practice of authoring arguments through processes… Following the contemporary model, procedural rhetoric entails expression—to convey ideas effectively… A theory of procedural rhetoric is needed to make commensurate judgments about the software systems we encounter every day and allow a more sophisticated procedural authorship with both persuasion and expression as its goal. Procedural rhetorics afford a new and promising way to make claims about how things work [emphasis in original].” Bogost, Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007), 28–29. ↩

-

Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011). ↩

-

Yuts, interview with John D. Davis and Bryan E. Norwood, December 19 and 24, 2022; Yuts, “NORCO,” Baumer Lecture Series, September 21, 2022, The Ohio State University, Columbus, link. ↩

-

Yuts, interview. ↩

-

Yuts, interview. ↩

-

Sylvia Wynter, “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,” Savacou 5 (June 1971): 95–102. ↩

-

Wynter, “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,” 97, 100. ↩

-

J. T. Roane, “Plotting the Black Commons,” Souls 20, no. 3 (July 3, 2018): 239–66. ↩

-

J. T. Roane, Dark Agoras: Insurgent Black Social Life and the Politics of Place (New York: New York University Press, 2023). See also Diane Jones Allen, “Living Freedom through the Maroon Landscape,” Places Journal, September 2022, link. ↩

-

Yuts, interview. ↩

-

Bryan Norwood, “Museum, Refinery, Penitentiary,” Places, March 2021, link. ↩

-

Wynter, “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,” 99. “Global racial empire” comes from Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, Reconsidering Reparations (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022), where it is used as a metonym for racial capitalism. ↩

-

Sylvia Wynter, “The Ceremony Must Be Found: After Humanism,” boundary 2 12/13, no. 3 (1984): 19–70. Quotes from Sylvia Wynter, “The Ceremony Found: Towards the Autopoetic Turn/Overturn, Its Autonomy of Human Agency and Extraterritoriality of (Self-)Cognition,” in Black Knowledges/Black Struggles: Essays in Critical Epistemology, ed. Jason R. Ambroise and Sabine Broeck (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2015), 185. ↩

-

Wynter, “The Ceremony Must Be Found,” 29. ↩

-

Wynter, “The Ceremony Must Be Found,” 34–35. ↩

-

Wynter, “The Ceremony Found,” 189. ↩

-

Wynter, “The Ceremony Must Be Found,” 37, 56. ↩

-

See Albert Thrasher, “On to New Orleans”: Louisiana’s Heroic 1811 Slave Revolt (New Orleans: Cypress Press, 1996). ↩

-

This framework appears in both Wynter, “The Ceremony Must Be Found” and Wynter, “The Ceremony Found,” but see also Sylvia Wynter, “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, after Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument,” CR: The New Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (Fall 2003): 257–337. ↩

-

“Dysselection” is a term Wynter uses to set in contrast to narratives of evolutionary “selection”; Wynter, “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom,” 310ff, and Wynter, “The Ceremony Found,” 199ff. ↩

-

Wynter, “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,” 101. ↩

-

Julius Scott, A Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution (London: Verso, 2018). ↩

-

See Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 6. ↩

-

Walter Johnson, “On Agency,” Journal of Social History 37, no. 1 (2003): 118, 121. ↩

-

On flesh, see, in particular, Alexander G. Weheliye, Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014). ↩

-

Wynter, “The Ceremony Found.” ↩

-

On the slippage in the term “America” in relationship to the built environment, see, in particular, Ana María León Crespo, “Plains and Pampa: Decolonizing ‘America,’” Harvard Design Magazine, no. 48 (Winter 2021): 48–49. ↩

-

Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic (Boston: Beacon Press, 2000). ↩

-

Wynter, “The Ceremony Found,” 188, 192, 230. ↩

-

On Fanon’s “gaze from below,” see Wynter, “The Ceremony Found,” 194. ↩

-

On “history from below,” see, for example, Marcus Rediker, “The Poetics of History from Below,” Perspectives on History (September 2010), link. ↩

-

C. L. R. James, Beyond a Boundary (New York: Pantheon Books, 1983 [1963]). ↩

-

See James, Beyond a Boundary, 17. ↩

-

Wynter, “The Ceremony Found,” 214. ↩

-

Wynter, “The Ceremony Found,” 222. ↩

-

This threat has been quite real. “While the control structure at Old River was shaking, more than a third of the Mississippi was going down the Atchafalaya. If the structure had toppled, the flow would have risen to seventy per cent. It was enough to scare not only a Louisiana State University professor but the division commander himself. At the time, this was Major General Charles Noble. He walked the bridge, looked down into the exploding water, and later wrote these words: ‘The south training wall on the Mississippi River side of the structure failed very early in the flood, causing violent eddy patterns and extreme turbulence. The toppled training wall monoliths worsened the situation. The integrity of the structure at this point was greatly in doubt. It was frightening to stand above the gate bays and experience the punishing vibrations caused by the violently turbulent, massive flood waters.’” John McPhee, The Control of Nature (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1989), 47. ↩

John Dean Davis, PhD, is a historian and assistant professor at The Ohio State University. He studies construction, technology, and the environment in the Americas, and is currently writing a book about engineering and landscape in the US during Reconstruction.

Bryan E. Norwood, PhD, is a historian and an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin. His research focuses on architecture and building practices in the United States and the Atlantic world in the long nineteenth century.