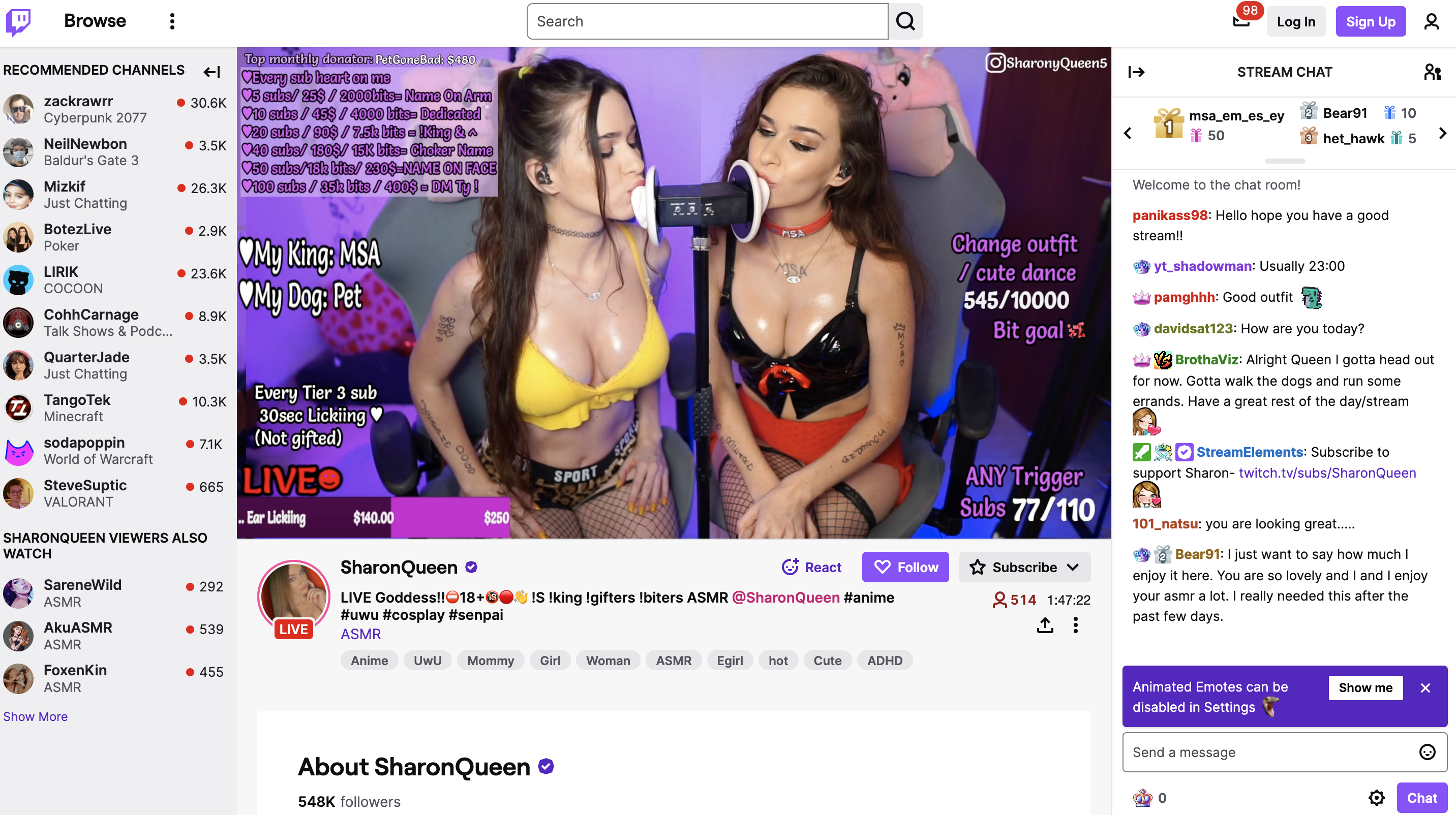

i m so thankful for beautiful women

I just want to say how much I enjoy it here. You are so lovely and I and I enjoy your asmr a lot. I really needed this after the past few days.1

Praise for the Twitch streamer on-screen—a woman whose oiled-up cleavage and soft kisses into an ear-shaped microphone have drawn in a crowd of over five hundred live viewers—continues to filter into the chat.

The streamer, SharonQueen, is one of the many ASMR (autonomous sensory meridian response) streamers active on Twitch. She is well-lit and in focus, sitting on a gray office chair against a backdrop of purple light and flanked by plush objects that read as soft, cozy, intimate. The careful curation of this evocative aesthetic set within a domestic space serves as an act of digital placemaking that is common in the ASMR category, where one can typically find female and femme streamers putting on sensual performances that involve using props or whispering into and lightly tapping a microphone to convey a sense of pleasure—traditionally a relaxed, tingling sensation is meant to ensue, but an implied eroticism can also underscore these performances. While many of the purported 35 million daily viewers on Twitch are tuning in to watch livestreams of video gameplay, there are also numerous other categories for content ranging from sports and fitness to art, cooking, and casual conversation.2 Streamers in each of these categories participate in placemaking practices that provide insight into the construction of digital cultural spaces.3 Within the ASMR category, performers offer an experience of intimate proximity, whether characterized by overt sexuality or not, to a community of viewers who are engaged through screen and sound, and who use the chat as a space of connection. These streams are often broadcast from bedrooms or other domestic spaces, implying a quasi-invitation into the private life of the streamer. Yet while the success of many ASMR livestreams comes from the sensuality of the performance and the production of a space of affective pleasure, they are notably devoid of overt sexuality.

This restriction both of outright sex work and of content that may be read as “sexual” is outlined in Twitch’s community guidelines, which specify a strict regulation of sexual content in favor of fostering “safety” and “community.” Unsurprisingly, it is the bodies of female and femme streamers that often become the subject of heightened scrutiny. These guidelines serve to arbitrate social conduct, and they notably define streaming as a “public activity.”4

But which public, and for whom? The publics forged through Twitch are intimate in nature, whether they involve an ASMR streamer in their bedroom or a video game livestreamer in their parents’ basement, but they are also being created under the purview of a series of rules dictating the acceptable presentation of setting, behavior, and the body. In putting forth these malleable regulations, Twitch surfaces an axis of exclusion that renders certain bodies and certain publics constantly subject to scrutiny or penalty, at the whim of the company along unspoken gendered, classed, and racialized lines. Many of the publics that Twitch enables are consistently skirting the limits of acceptability. They can thus be understood as disallowable, constantly on the cusp of impermissibility. How can the boundaries of allowability be rearticulated to account for the range of densely personal and affective relations and identities that constitute publics both on and offline?

Streaming’s origins

Twitch.tv was launched in 2011 as a gaming platform under the purview of its parent site, Justin.tv. Created in 2007, Justin.tv hosted various forms of online broadcasting, and its origins are undeniably performative: wearing a baseball cap fitted out with a mobile camera, one of the site’s founders, Justin Kan, broadcast his life 24/7 before eventually transforming the site into an open network for others to broadcast—or lifecast—from.5 Justin.tv was shut down in 2014, but Twitch.tv remained active and was purchased by Amazon soon thereafter. Amazon’s acquisition can be understood as capitalizing on the rising popularity (and profitability) of livestreaming, and Justin.tv can be read as one of many sites responsible for propelling it into the mainstream. But, though Justin’s lifecasting project gained significant notoriety and Justin.tv encouraged a generative form of self-presentation across its channels, both were building on a lineage of other similar performances: those largely popularized by webcam performers (or “camgirls”) in the 1990s.

With the rise of the internet came new opportunities to explore performance, technology, and connection. Early adopters of the internet as a site of networked experimentation included many young women who, broadcasting from their bedrooms, would stream intimate moments of their lives. Among these early cam performers were Ana Voog, whose twelve-year-long project (1997–2009) anacam was “the internet’s 1st 24/7 art-life cam,”6 and Jennifer Ringley, whose daily life in her college dorm was broadcast 24/7 via JenniCam (1996–2003). While anacam was categorically horny, raw, and experimental, JenniCam was intended to be a reflection of “real life.”7 Ana and Jenni were among the earliest camgirls and thus have garnered renewed attention over the years, but many others were also using their webcams to flesh out intimate publics.8 Amid practical questions of technical know-how (how to stream from multiple webcams? how to set up a site with a chat?) were also broader and more expansive ambitions to explore spaces of collectivity and intimacy in new ways. These livestreaming practices were inevitably predicated on expanding understandings of what a “public” could be. Though early webcam performers approached their streams from diverse vantages, in broad strokes they were seeking to carve out publics characterized by agency, safety, curiosity, and connection, pushing back against existing boundaries as if to question the delimitation of life as a private thing. As Ana Voog has articulated in recent years, “I thought the internet would be a way for me to circumvent everything that stood in my way: a tool for the unheard. We could speak out and completely bypass the hierarchical, patriarchal system in place to keep us silent.”9 This ethos still rings true for many who turn to the internet to seek out other ways of being in the world. Early webcam performers pushed the knotty contours of pleasure and domestic life—“real life”—into the public sphere, while simultaneously laying a foundation for future forms of self-broadcasting, including camming, as they exist today.

Fast forward to 2023: Sex workers and webcam performers who broadcast on sites like Chaturbate, MyFreeCams, or Onlyfans are often able to actualize work environments that can be safer and more autonomous than street-based sex work,10 but they continue to face social stigma, and their presence as streamers on Twitch is tightly monitored. Twitch would not exist if not for camming, and yet it remains an often-inhospitable place for sex workers. Its dual roles as streaming site and community space coalesce through community guidelines constantly in flux, shifting in response to changing definitions of acceptability in public. These guidelines ultimately play a key role in defining streamers’ content, backdrops, and forms of self-presentation.11 The strict policy to regulate and remove sexually suggestive content across Twitch channels means that sex workers, who often succeed at monetizing their work by operating across multiple platforms, must censor their personas and performances to fit within the bounds of virtual acceptability. The policing of sex workers’ online presences also extends past the digital confines of the site itself: streamers are only permitted to link to nonexplicit content on their pages, necessitating a virtual chain of links to reach sexually explicit work. Even so, Twitch capitalizes on their cross-platform fanbases.

The hypervigilance with which sex workers are monitored on Twitch is paralleled by the treatment of female streamers more generally. One of the most common sites of regulation outlined in Twitch’s community guidelines is the body: beyond the moderation of behavior, it is often clothing that serves as a litmus test of virtual appropriateness. If clothing is deemed too “sexually suggestive”—a vague and subjective label, even insofar as Twitch’s community guidelines suggest—streamers run the risk of getting their accounts suspended. It is undeniably female and femme streamers who bear the brunt of these penalties, with the female body always at risk of being inappropriate simply due to the perception of it as inherently sexual,12 a perception compounded by vectors of body size, race, and transness. This is on top of the fact that marginalized groups often face harassment in the gaming world, as exemplified by the frequency with which female and femme streamers must deal with misogynistic treatment, such as in cases where they are accused of using their good looks to take streams away from people who truly “deserve” it.13 Uncoincidentally, female video game streamers face harassment by being called “camgirls,” a moniker that is used to insinuate that they are not valid on the platform whether or not they actually do work as webcam performers. The very use of “camgirl” as a slur only serves to further stigmatize sex work at large.14 As Amanda Cullen and Bo Ruberg have articulated, Twitch’s community guidelines “further undermine the legitimacy of women in gaming spaces such as livestreaming by suggesting that their bodies must be actively regulated in order to make a streaming platform a [sic] ‘positive’ and ‘safe’ for a mainstream gaming community.”15

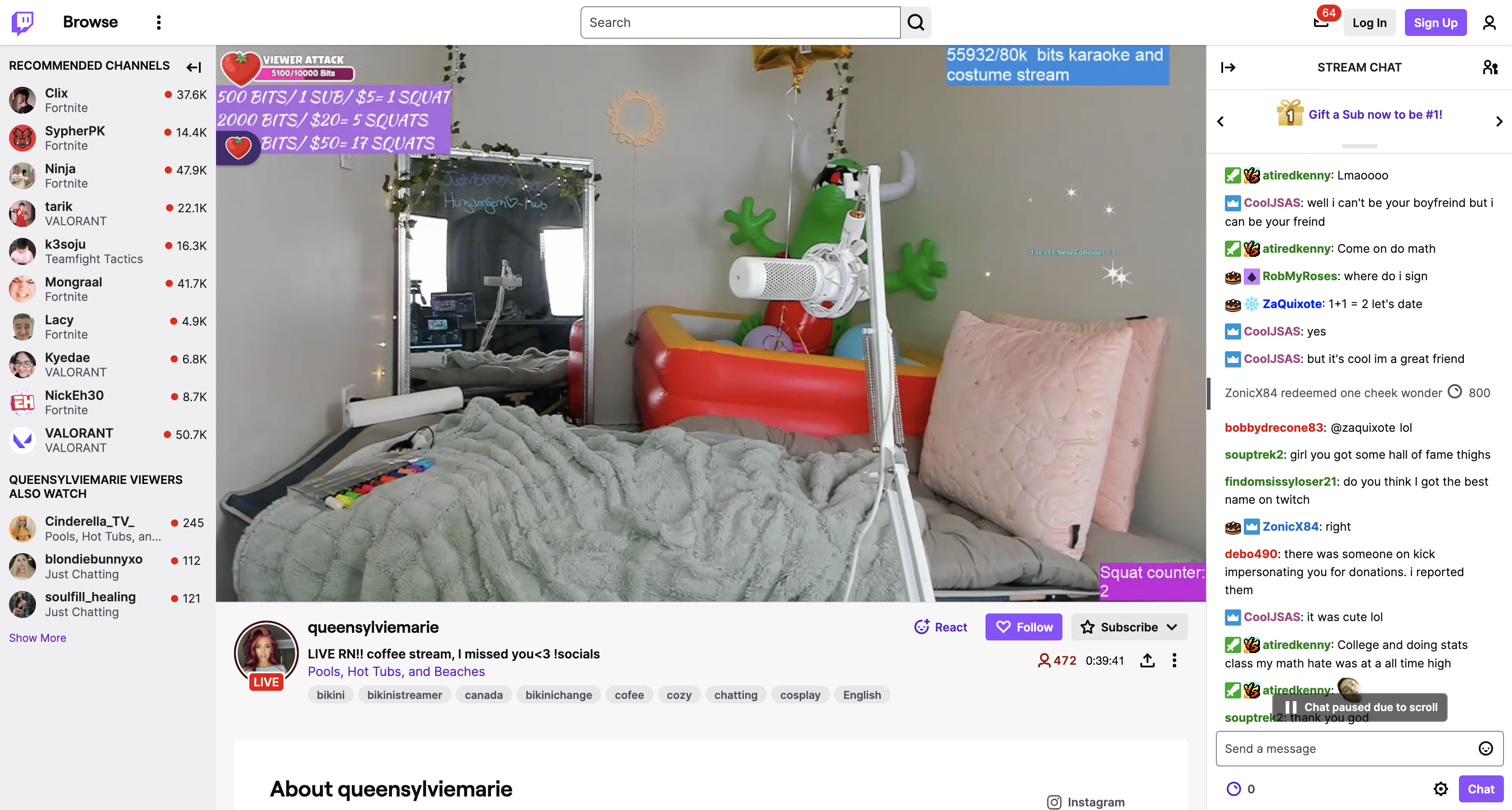

According to Twitch's community guidelines, streamers are allowed to show cleavage, but not underbust; certain quadrants of the breast perplexingly cross the threshold of allowability, while others do not. In addition, appropriateness and allowability are determined by context: it would not be appropriate to stream yourself cooking in a bikini, but it would be appropriate to stream yourself cooking in a bikini if you were standing in front of a pool. The lines being drawn around what can be considered appropriate are rendered nearly arbitrary. In 2021, Twitch introduced the “Pools, Hot Tubs, and Beaches” category to contain content that involved streamers in swimwear, and by extension placate the growing number of Twitch users expressing outward frustration at the presence of these streams on the platform. The category now largely hosts content that is sexually suggestive, but not overtly or explicitly so.16 Because the presence of water seems to be the necessary requirement if one wishes to stream in a swimsuit, streamers creatively compound spatial settings: it is not uncommon to see someone sitting in their bikini on a gaming chair or a bed, with an inflatable pool in the background, casually chatting with a community of viewers whose comments range from benign compliments to sexual remarks or intellectual lines of questioning. These clever spatial work-arounds are among the most ingenious and intriguing spacemaking practices on Twitch, with backdrops acting as coded signifiers. Wearing a swimsuit while chatting with viewers from a bed may imply a certain sexual intimacy that would seem to violate Twitch’s guidelines, but the presence of an inflatable hot tub makes it permissible in Twitch’s terms. Nevertheless, these streamers remain in a vulnerable position, as the body continues to be a site of regulation both by the platform and its users.

The crux here is not the plain fact that content on Twitch is regulated; rather, it is the notion that these regulations are vague and often inconsistent, while being framed through a lens of publicness and around social norms deemed to be universally understood.17 This can clearly be seen in the way that Twitch’s community guidelines regulate nudity in video gameplay, where streaming sexual content in permitted games is allowed for “as much time as is required to progress.”18 The “public” thus becomes an objective space that inevitably—and actually—excludes certain members.

Spatializing online publics

Despite their analogous origins and contemporary similarities, there is a distinct and gendered divide between the present-day perception of cam performers and video game livestreamers. This perception—often manifesting in the form of stigma, harassment, or discrimination toward sex workers, cam performers, and female and femme livestreamers—can be seen to operate external to the online spaces carved out by streamers themselves, but also reverberates within wider online communities. Yet even if livestreamers and cam performers do not face the same forms of public scrutiny or directly engage audiences in the same way, they can be considered parallel forms of affective and material labor.

To be successful on their respective (or shared) platforms, both cam performers and livestreamers must define and maintain a persona, engage with their audiences, hone their technical skills, curate a backdrop, and perform on-screen, among many other forms of work. Both types of broadcasting are ultimately predicated on forming intimate connections with a viewer, for it is these connections that allow them to gain a following and monetize it. Bo Ruberg has used labor as an analytic lens to call into question the distinction between cam performers and livestreamers, arguing that, given the similarities and overlaps in the work they do, one could not be said to be more legitimate than the other. But even given these overlaps, Ruberg notes a critical distinction: “Self-broadcasting may be ‘hard work’ for all involved, but [for] some groups—like sex workers and women, among others—it is harder than for others.”19

Highlighting the parallel labors of cam performers and livestreamers also allows us to better interpret the spacemaking practices that reinforce their online communities. Space in this sense can be considered in terms of the space of the screen—the chat box, the streaming window, the wider platform of Twitch, and so on—but also in terms of the physical spaces that cam performers and livestreamers create and work from.20 A critical site to emphasize in this context is that of the bedroom: the site of many (online) performances. We can think back to the work of early camgirls, who transformed the bedroom into a public space in real time; or to that of online sex workers today who, often broadcasting from domestic spaces, operate from a place of agency, safety, and pleasure to put on erotic performances. The bedroom as a broadcasting location implies a heightened degree of access to the intimate life of the streamer, and imbues a sense of personal connection between performer and viewer in a networked public.21 On Twitch, which construes sex work as wholly disallowed, many streamers—particularly, but not exclusively, in the ASMR and Just Chatting categories—use their highly curated backdrops as atmospheric context cues, employing lighting, furniture, and objects to indicate what their streams entail. For instance, a streamer in the Music category may use flashing lights and metallic streamers to create the atmosphere of a club, while a video game streamer may opt for a dimly lit backdrop with monotone neon lights to create a subtle atmosphere but not detract from the gameplay visually occupying the main frame. When contrasting the spacemaking practices of erotic cam performers with those of male video game livestreamers, the latter can be seen to often stream from generic interiors as a way of distancing themselves from the implied eroticism of the bedroom and, by extension, the work of webcam performers engaging in forms of online sex work.22 The variety in spacemaking practices between streamers covertly serves to imply the degree to which the streamer embraces the intimate possibilities of their work.23

Given Twitch’s strict regulation of sexual content, the bedroom can also be seen as a means of coding eroticism into allowable streams (though, crucially, this is not a universal indicator). Many streamers utilize the bedroom or other contextual elements to emphasize the range of erotic possibilities that could unfold if the viewer sticks around for just long enough. These streams brush up against, manipulate, and outsmart the boundaries of the allowable “public” espoused by Twitch—but this line of acceptable publicness also often wears too thin, leaving streamers at risk of suspension or outright ban. The disallowable publics being fostered on Twitch are always subject to censorship.

When streamers and cam performers engage with their audiences in the stream and the chat—itself an active and generative, though often chaotic, community space—they are performing what Angela Jones refers to as “embodied authenticity,” which is to say, they are offering a stylized and performed presentation of their “real,” authentic selves to the viewer or client. As Jones elaborates, “While it is no secret to most customers that cam models are working, the appeal of the erotic webcam market is that performers are perceived as amateurs—as real people, who have turned on their webcams.”24 Similarly, the success of non–video game streamers on Twitch often lies in their ability to create an environment that feels somehow personal and bound up in conversation, recognition, or familiarity, and thus encourages recurring engagement. In turn, through engagement in these virtual places, viewers of camming sites or Twitch streams also invite the streamer into an intimate part of their lives, often turning to them to meet intimate needs—not only those sexual in nature but also those of friendship or relaxation. The chat becomes a space for self-elaboration for viewers in its capacity to manifest connection across digital divides, especially when the performer on-screen responds directly to a comment or request.

The forms of engagement that arise through the performance of embodied authenticity can create parasocial bonds in which the viewer feels a close intimate connection to or sense of friendship with the performer on their screen, but which the performer does not reciprocate. These relationships echo those foisted on celebrities, as people often feel a sense of entitlement to celebrities’ personal lives and express disapproval when these celebrities behave in a way that seems out of character. Such bonds can foster an assumed familiarity that makes it easy for boundaries to be crossed, and even for safety to be put in jeopardy as lines of consent become blurred. An example of this behavior can be found in certain interactions with female Twitch streamers in which viewers use the space of the chat to ask personal questions that connote an assumed right to know, like “Do you have a boyfriend?” The feigned familiarity between viewer and streamer, or client and cam performer, represents one half of a Venn diagram of parasociality: emergent forms of online engagement express both commonality and difference with age-old sex work parasociality, such as the customer who thinks he is “dating” the dancer in the club.

The bedroom or other domestic space bolsters a sense of embodied authenticity by conceptually relocating these performances from the space of labor to that of the personal and the intimate, and performing embodied authenticity online may at times also mean paring back the complexity of a physical setting. On erotic camming sites, it can be the overproduction of space that limits the capacity of a performer to deliver embodied authenticity. While traditional pornography is often viewed as “scripted” sex and thus less “real,” camming is perceived as more “authentic” because it invites the client to interactively participate in and thus shape the way a performance plays out.25 Overthought spatial settings run the risk of reducing the realness. By camming from a space that appears to be more unfiltered and thus more authentically intimate, the performance seems like less of an “act” and more of a pleasurable exchange.

The dynamic of spatial restraint versus abundance surfaces an intriguing duality: on Twitch, space can either be carefully, meticulously curated to provide affective clues about the creation of a particular public or it can be wielded as an apparent disavowal of often feminized spacemaking practices, instead offering a sense of nonchalant “realness.” The success of streamers in the former category likely relies on their capacity to entice viewers who are active in the chat or through other modes of engagement. Given the intimate origins of the livestreaming industry and the absence of explicit sexual content on Twitch, embodied authenticity could be seen as implicit across self-broadcasting contexts, though it is a form of self-presentation that differs across various online publics. And, regardless of their physical backdrops, streamers and sex workers who work via livestream can be understood as engaging in a form of spatialized intimacy and community building with their viewers.

Riot in the chat

Me and the chat, we got a relationship. We in a friendship relationship.26

Popular Twitch streamer Kai Cenat is now on-screen. Kai’s stream does not seem to follow the logic of careful backdrop curation (though one can assume he has nevertheless put thought into it): instead, he is streaming from what looks like a suburban basement in the United States, with cool fluorescent lighting giving an ambience of general nonchalance while the armrests of his office chair are held together with duct tape in three different colors. Unlike streamers in the ASMR category like SharonQueen, who curate a particular aesthetic predicated on sensuality and softness, Kai seems to emphasize relatability and, notably, embodied authenticity. There is no denying that he is successfully mobilizing the chat, which is blowing up as he streams his reaction to a video of a six-year-old rapper flaunting stacks of cash.

Kai’s popularity can in part be attributed to his loud and rowdy persona, which in turn spurs engagement in the chat. Twitch chats cater to a variety of community needs: they can support collaboration, offer a political platform, cultivate intimacy, or simply operate as an outlet for shitposting. They are tightly monitored by moderators, but also act as transformative conduits for various publics and help contribute to the sense of community that Twitch emphasizes. In Kai's streams, he rallies his viewers by interacting directly with their comments, often acting in a way he knows will provoke spirited reactions. The dynamics of affective performance and relatability are ever present on his channel, as he aims to make viewers feel like they are casually hanging out with him. In a 2021 stream now available on YouTube, Kai hires a professional cuddler—a woman named Amina—and streams from his bedroom, seeming to further invite his audience to be part of his intimate life.27 Despite the platonic nature of Amina’s work, Kai uses the site of the bedroom and the physical, erotic intimacy it implies to animate his viewers. The stream is less a disavowal of the implicit parallels between camming and streaming than a way to make fun of them—a dynamic evidenced in the way the woman invited to participate, as well as Kai himself, are made fun of throughout the stream. From the moment Amina enters the room, the chat is hyperactive, emphatically insulting her physical appearance while also jokingly shaming Kai for his role in the exchange. To be in on the joke is to deride sexual (and sexualized) labor and those who consume it.

In early August 2023, Kai found himself at the center of a national controversy when he announced that he would be giving away free PlayStation 5 consoles in Manhattan’s Union Square Park. Given his influencer status and huge popularity on Twitch, thousands of people—many of them Black teenagers—showed up amid heavy police presence in hopes of snagging a console, or simply being present for the excitement. As the day unfolded, intensity built, and sixty-five people were arrested. Kai, himself a young Black man, was taken into custody and charged with felony first-degree rioting, as well as misdemeanors of inciting a riot and unlawful assembly.28 Despite the negative media portrayal of the giveaway event, Kai’s popularity on Twitch and other social media sites remained high because of his capacity to maintain his authentic self-presentation amid the chaos.29 He acted true to form, and his viewers, seeing him as a friend and not just a celebrity, were likely to support him. Much of the condemnation in the media after the fact was directed at racialized young people attending the giveaway, implying that their actions as a collective were inherently steeped in volatility. But, as Jackie Wang articulates, “The biopolitical construction of juveniles as subjects defined by irrationality marks this subset of the population as a calculable risk that must be pre-emptively managed, for they have been deemed incapable of self-government and self-determination.”30 The hyper-criminalization of Black, Indigenous, and other people of color plays a key role in this construction, further reinforcing the mechanisms of racial capitalism in city space.31 This presupposition of risk entrenches dynamics of carcerality and white supremacy on an urban scale and presents chaos as inevitable, with public space only made “safe” through the presence of police. These effects also trickle into digital publics, which are similarly governed by standards of “community safety.”

The giveaway event could be read as simply a case of some members of a crowd of youths getting out of hand, but the layers of virtual and physical community-building that were subject to agitation and potential carcerality here lead us to seek a more nuanced reading. The events that unfolded seem to imply a frustrating untranslatability of the digital into the physical—or, moreover, an inherently carceral result when such translation occurs. This result comes into sharper focus when read in racial terms, as it is those who inhabit racialized bodies who are impacted most by the violence of the carceral state. In operating as poor simulacra of digital communities, IRL publics take on their own characteristics, in turn making marginalized identities visible. In doing so, they become disallowed. Conversely, online publics also become a way to escape the carcerality of the offline world, especially for those whose ways of being in that world exist along a delicate line of allowability. Many people turn to the internet as a place to connect with others like them who have been somehow sidelined in their offline lives. These publics, both emancipatory and limiting, can serve as a place of connection or a tool to further entrench social divides. Take, for instance, the use of the internet by policing bodies to track down protesters, or the FBI’s nefarious use of online chatrooms to radicalize vulnerable teens.32

A parallel can again be drawn between sex work and livestreaming: while sex work on camming sites operates under a thin veil of legality, in-person sex work remains essentially illegal in the United States, Canada, and a large number of countries globally. Similarly, as with the Kai Cenat incident, when the dynamics of online communities are translated into the IRL public sphere, a carceral logic is imposed to suppress the forms of connection deemed appropriate for the online public advocated for and protected by Twitch. There are, in short, many behaviors that present themselves in digital publics which are not translatable to physical ones. What does this mean for our conceptions of the collective? As Lauren Berlant prompts us to inquire, “How can we think about the ways attachments make people public, producing trans-personal identities and subjectivities, when those attachments come from within spaces as varied as those of domestic intimacy, state policy, and mass-mediated experiences of intensely disruptive crises?”33 How can we create publics that are able to account for the myriad types of connections increasingly being forged online, and how can the policed boundaries of these various publics begin to melt together? As things presently stand, the edges of these disallowable publics are tenuous at best—perhaps the answer lies in the symbiotic logic of the chat.

-

Comments by various users on a Twitch livestream by SharonQueen entitled “LIVE Goddess! 18+ !S !king !gifters !biters ASMR @SharonQueen #anime #uwu #cosplay #senpai,” October 1, 2023. ↩

-

“Facts and Figures,” Twitch.tv, accessed October 2023, link. ↩

-

Bo Ruberg and Daniel Lark, “Livestreaming from the Bedroom: Performing Intimacy through Domestic Space on Twitch,” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 27, no. 3 (2020): 2. ↩

-

“Community Guidelines,” Twitch.tv, accessed October 2023, link. ↩

-

“Justin.TV Teams Up with On2 and Opens Network,” TechCrunch, October 2, 2007, link. ↩

-

“anacam, the internet’s 1st 24/7 art+life cam!!,” Anavoog (website), last modified February 1, 2007, link. ↩

-

Theresa M. Senft, Camgirls: Celebrity and Community in the Age of Social Networks (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2008), 42. ↩

-

Theresa Senft offers five loose categories for these performances: “the real-life cam, the art cam, the porn cam, the group house cam, and the community cam.” See Senft, Camgirls, 38. ↩

-

Ana Voog, “I Was One of the Most Famous People Online in 1998—Then I Disappeared,” Vice, June 22, 2018, link. ↩

-

Angela Jones, “Sex Work, Part of the Online Gig Economy, Is a Lifeline for Marginalized Workers,” The Conversation, May 17, 2021, link. ↩

-

Amanda L. L. Cullen and Bo Ruberg, “Necklines and ‘Naughty Bits’: Constructing and Regulating Bodies in Live Streaming Community Guidelines,” in Proceedings of FDG’19, ACM, New York, USA (2019): 1, link. ↩

-

Cullen and Ruberg, “Necklines and ‘Naughty Bits’,” 7. ↩

-

Nathan Grayson, “Streamer’s Hateful Rant Revives Debate about Women on Twitch,” Kotaku, November 15, 2017, link. ↩

-

Bo Ruberg, “Live play, live sex: The parallel labors of video game live streaming and webcam modeling,” Sexualities 25, no. 8 (August 2022): 1036, link. ↩

-

Cullen and Ruberg, “Necklines and ‘Naughty Bits’,” 8. ↩

-

“Let’s Talk about Hot Tub Streams,” Twitch (blog), May 21, 2021, link. ↩

-

Cullen and Ruberg, “Necklines and ‘Naughty Bits’,” 5. ↩

-

“Community Guidelines: Attire,” Twitch.tv, accessed October 2023, link. ↩

-

Ruberg, “Live Play, Live Sex,” 1036. ↩

-

Ruberg and Lark, “Livestreaming from the Bedroom,” 4. ↩

-

danah boyd, "Social Network Sites as Networked Publics: Affordances, Dynamics, and Implications," in Networked Self: Identity, Community, and Culture on Social Network Sites, ed. Zizi Papacharissi (New York: Routledge, 2010), 39–58. ↩

-

Ruberg and Lark, “Livestreaming from the Bedroom,” 3. ↩

-

Cullen and Ruberg, “Necklines and ‘Naughty Bits’,” 14. ↩

-

Angela Jones, Camming: Money, Power, and Pleasure in the Sex Work Industry (New York: NYU Press, 2020), 6. ↩

-

Jones, Camming, 47. ↩

-

Kai Cenat, Twitch livestream on October 18, 2023 at 8:58 pm EST. ↩

-

Kai Cenat Live, “I Hired a Professional Cuddler Live on Stream,” YouTube video, November 9, 2021, link. ↩

-

Mary Whitfill Roeloffs, “Kai Cenat Due in Court Next Week: Here Are Other Influencers Whose Antics Led to Arrests,” Forbes, August 10, 2023, link. ↩

-

Will Bedingfield, “The Twitch-Fueled Catastrophe of Kai Cenat’s New York City Giveaway,” Wired, August 9, 2023, link. ↩

-

Jackie Wang, Carceral Capitalism (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018), 197. ↩

-

M. M. Ramírez, “Policing, Racial Capitalism and the Ideological Struggle over Public Safety,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research (September 15, 2022), link. ↩

-

Murtaza Hussain, “The FBI Groomed a 16-Year-Old with ‘Brain Development Issues’ to Become a Terrorist,” The Intercept, June 15, 2023, link. ↩

-

Lauren Berlant, “Intimacy: A Special Issue,” Critical Inquiry 24, no. 2 (Winter 1998): 283, link. ↩

Alexandra Pereira-Edwards is a designer, writer, and researcher based in Tiohtià:ke/Montréal, Canada, where she works as an Editor at the Canadian Centre for Architecture. Having worked variously in publishing and product design, Alexandra holds a Master of Architecture from Carleton University and has published her work internationally. Her research explores the dynamics of power, infrastructure, and affect as they relate to space, with a focus on intimacy as a lens through which to understand hidden systems in built and digital environments.