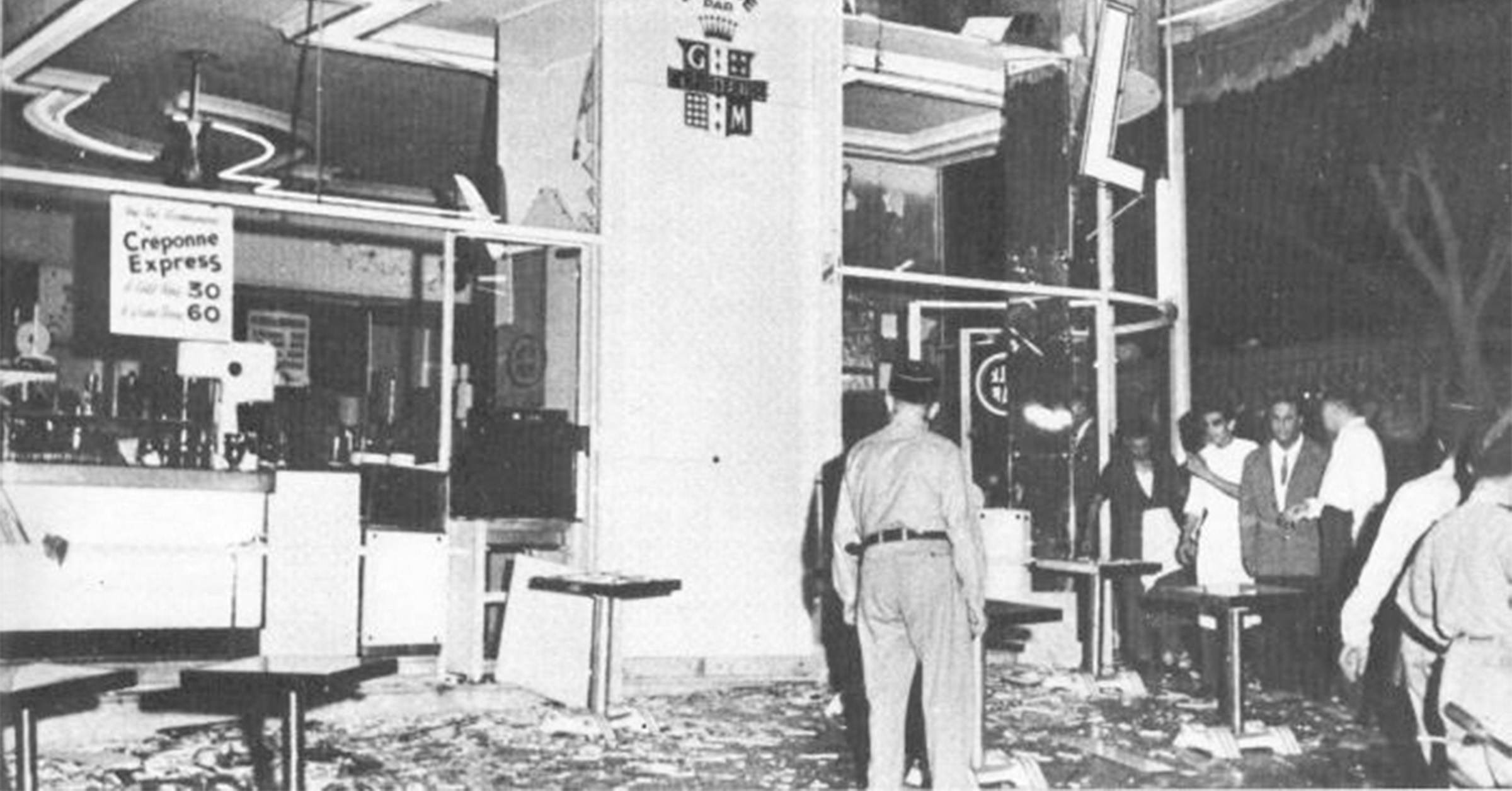

... to time an explosion…

6:25, 6:30, 6:35—the dates and times for which the three bombings had been set.

We took the simulations seriously, timing our route on foot from Bab El Oued to reach each of our targets.

We noted when the crowd peaked—between 17:30 and 20:00.

I rehearsed the walk from Rue de Borely la Sapie to my target, to choose the best route in light of the police and army checkpoints and roving patrols, to note their frequency and number, and to measure the time needed for the journey.

The instructions were to leave at most eight to ten minutes before the explosion. I had arrived about twenty-five minutes before it.

I estimated that fifteen minutes would be enough to set my beach bag in the right position, order, eat, pay, and leave.

At the same time, I worried that fifteen minutes was too long for me not to be spotted. I didn’t trust the wall clock in front of me.

Panic began to overtake me when I realized how quickly the hands of my watch were turning.

Inside the bag was a mechanical device—not a big round clock one imagines—that made no sound.

—Zohra Drif, member of the Algerian Front for National Liberation (FLN), recounting the placing of a bomb in the Milk Bar, a café frequented by French settlers in Algiers, on September 30, 1956.1

The precise calibration of “French time” offered a predictability exploited by the Algerian resistance. Attacks were mapped out as timelines, wound to the colonizer’s watch and integrated into one synchronized temporal framework regulating the occupiers’ routine and movement through the city. The bomb inside Drif’s bag becomes a symbiotic object: tuned to French time by the Algerian resistance, it—and the timeline elaborated for its placement—straddles two tempos, synchronizing them.

Necessary Decay

In 1959, the French would refer to their presence in Algeria as necessary “pour éviter le pourrissement de l’Algérie” (to avoid Algeria’s decay). In warning against the temporal degradation of Algeria—pourrissement translates to the act of decay—French positioned themselves as regulators of its development, signaling their control over the evolution of the territory as a whole. This notion of decay pointed to an essentializing temporal understanding of Algeria, one predicated on a Eurocentric idea of development and modernity. This is not to say that Algeria became the site of a clash between two epistemologies, one French and the other Algerian—that would be too simple. Rather the colonial venture, by designating Algeria as a site of extraction within this matrix of modernity, tied it inextricably—if asymmetrically—to the fate of the metropole. In this alien framework, imposed rather than adapted, Algeria, left to its own devices, could not but fail. The territory was condemned to underdevelopment, constantly on the brink of decay, were it not for its French “saviors.” In so doing, the French imposed their own temporality—in both an immediate, embodied sense and in a broader, historical sense—one to which all territories had to be synchronized. French operations during the war of independence from 1954 to 1962 can therefore be read as a series of violent adjustments to Algerian time. Within France’s temporal framework, Algerian time was not fixed, defined, and proscribed, but rather multiple and limitless. In contrast, French colonial time has identifiable, explorable contours, predicated on state-mandated norms of control and productivity, leading to a redesign of the territory and its bodies.

Examining spatial interventions reveals that the occupation aimed to accelerate the Algerians to acceptable levels of development. Multiple operations at scales ranging from the territory to the intimacy of the body complicate our understanding of time, proving the latter's agency in configuring the occupation. While it adds yet another layer to our understanding of strategies of control at play in French Algeria, where time, as a colonial tool, reorganized space to produce a legible population and territory, reading time in this way also helps challenge the logic, pace, and synchronization of occupation, as Algerians formulated tactics of resistance in a landscape of counterpoints.

Checkpoints: A Spatial Pause?

Across the Algerian territory, checkpoints became symptomatic of French control over Algerian routine. Dotted along urban and rural paths, used daily, these checkpoints acted as a threshold between two time zones, adjusting each Algerian’s inner clock to a regulated French tick.2 After the outbreak of the war of independence in 1954 and the emergence of an active and organized resistance, the French military intensified its spatial and temporal control of Algeria’s major cities. The casbah of Algiers, populated by the colonized,3 became subject to practices of confinement by the French, who came to understand the salience of the casbah as the heart of the resistance.4 The French ran barbed wire along the casbah walls and installed five checkpoints to limit entry and exit. Their soldiers coordinated passage using an instant telecommunications network. The checkpoints were boundaries in space, but also in time: moments between the colonial city and the casbah.5 Long lines waiting to cross were a norm, so that each Algerian’s second was indefinitely prolonged, subject to the whims of the soldiers guarding the crossing. These encounters acted as temporal hiccups—the skipped second in the daily Algerian rhythm. Yet these thresholds were more than points along a dividing line. Instead, the messiness of transiting between two time zones expanded the crossing. Suspended in the thickened temporal membrane of the checkpoint, the Algerian no longer owned their time, made ambiguous and unpredictable by this moment of contact with the occupier. There was little ability to predict how long the crossing would take, or if the crossing would take place at all that day. The checkpoint’s temporal role was therefore twofold: on the one hand, it disrupted the Algerian’s clock; on the other, it established hierarchy between the two time zones. And yet, the checkpoint failed in its attempt to discipline the Algerian: by causing delays to the 24-hour cycle of productivity, it ironically disrupted aspirations to regimented punctuality.

The new bureaucratic apparatus required to manage these checkpoints not only intensified the population’s policing but also redefined it, molding individuals into subjects of the state, their identity prescribed by predefined metrics.6 Indeed, in January 1957, the French conducted a census of the inhabitants of Algiers, during which new identity cards were issued that included the name, address, occupation, and place of business of each person.7 These cards operated according to the logic of the checkpoint, translating the Algerian body into a series of attributes that the apparatus of occupation could compute. Marking the edge of the Algerian and European quarters of coastal cities, the checkpoints were therefore a crucial node in the formation of the Algerian subject, conditioning the smoothness of their movement on this registered identity. Furthermore, identifying an individual based on their occupation not only rendered one more legible to the state but also determined their mobility. Movement through the city for the purpose of work was implicitly sanctioned by the occupier. All other movement—movement deemed more erratic, breaking with the performance of capitalist rituals as registered on the card—required greater scrutiny, further checks. This marked the formal intrusion of the French state into the daily routine of their subjects, registering their internal clocks, linking their movement to occupation. In so doing, the checkpoint participated in the formulation of French time based on a capitalist framework, and systematic delays made clear the capacity of the French to both accelerate and slow down time. More generally, by defining the Algerian based on their labor capacity and obstructing their time, the French checkpoint revealed the importance of speed in relation to productivity in the occupier’s world, in which time became an invaluable commodity.8

Urban Reconfiguration as Acceleration

On the other side of the time-zone threshold, the French vastly reorganized Algerian cities to better accommodate their temporal logic, slicing through neighborhoods to optimize flows. As early as 1830, in a show of force, they carved out a large square dubbed the Place d’Armes in front of the palace of the toppled Ottoman dey. The move was more than symbolic: it inaugurated the selective remodeling of Algiers to accommodate the size and maneuvers of the French military. Indeed, technologies of containment, from large tanks to field battalions, required wide avenues. The lower casbah, stretching along the sea, was cut through to create two main arteries. Slicing through the city was a form of temporal reorganization: the three large, military-grade boulevards in the colonial extension of Algiers established new standards of efficiency, collapsing the time of travel between two points in the city by drawing the shortest possible vectors to shorten journeys and widening the streets to accommodate vehicles.9 The zoning of these new neighborhoods concentrated commercial activities: in the new European center, Algerian dwellings were cleared, and, in their place, the stock exchange was erected across from the commercial tribunal, making transactions as expedient as possible.10

In designing colonial Algiers, the French imposed a specific urban rhythm, a synthesis of capitalistic and militaristic logic.11 Yet while transforming the city, the French, for the most part, avoided the casbah. It was an aberration: unsynchronized and therefore, beyond those early cuts, ignored. Le Corbusier’s own 1932 proposal for the capital totally bypassed the casbah. After all, modernism had but one clock, by which the casbah, with its complex layout and dense residential fabric, did not keep time.

Referred to as “irrational” by generals and planners of the time, the casbah was in fact highly organized, with a complex urban system predicated not on speed but on “filtered access.”12 While the lower casbah by the sea catered to more public commercial activities, the upper casbah was more private and residential, full of narrow, winding streets and, often, dead ends—a physical embodiment of the intimacy of residents and their cultural practices. The upper casbah required an intimate understanding of its network—a logic of circulation based on memory and personal narrative rather than on timetables and transportation. Much of its activity remained out of sight: understated and discrete doors, not tall enough to frame an average height person, opened up to entire worlds, to palaces fitted with internal courtyards that themselves served as filters between public and private space, drawing interiors within interiors. A secondary layer of passageways connected various properties together so that the street itself became peripheral.13 In fact it was possible to avoid the street entirely, traveling from one house to another by terraces.14 A completely different form and pace of urban mobility happened here, one illegible by French standards.

Yet in the 1950s, the casbah was more than just a time sore. Host to myriad communities that had come to Algiers from Spain after the Reconquista but also elsewhere in Europe, Istanbul, and the Sahara, the casbah consisted of over fifty neighborhoods, each with its own administration, overseen by both a religious leader and a qadi (or judge). These administrative units were developed to maintain the casbah, as neglected structures risked being demolished by the French. In self-organizing an alternative system of administration and preservation, residents turned their backs on the occupiers and the casbah into a “counterspace,” one that represented the “oppositional voice of Algerians to colonial power.”15 The French forces would come to understand this system was itself a form of resistance to the ongoing occupation. Indeed, during Algeria’s war of independence, the French would penetrate the casbah to pacify the resistance. The assassination of the notorious resistance fighter Ali La Pointe by French parachutists from the air points to the violence of synchronization: the aerial killing can be read as a French acceleration of the casbah, rendering it legible enough to operate within. Guided by helicopters, parachutists, and snipers, the French conducted their operations from the air, overriding the conditions of the casbah on the ground that impeded their operations. From above, the entire casbah could be read as a homogenous entity.16 And this homogeneity was a time-based strategy developed in service of the occupation: in “flattening” the casbah, in creating smoothness, in facilitating ease of movement, the French could accelerate their operations to capture La Pointe. Parachutists could move into the zone without being subject to the casbah’s cadence imposed by the winding, labyrinthine streets, in which a first-time visitor could easily get lost, giving the upper hand to those with an intimate knowledge of its system of circulation. Once La Pointe’s hideout was discovered, the French forces rigged the walls of the house with plastic explosives, enough to “take out the entire neighborhood.”17 The French destruction of the house was therefore not simply collateral damage but rather a planned act to smooth out the landscape of the resistance.18

In the casbah, the foreignness of the colonial clock of the French military was especially stark, creating a need to synchronize the territory in order to make it legible not only to the military personnel but also to the technologies they employed. The sense of time to which the French were subject can therefore be complicated by an understanding of what their apparatus consisted of, and what range of movements and positions it required. While the case of the casbah points to the legibility of the space to a certain technological apparatus requiring a specific tempo for operations, the French reorganization of Algerian territory reveals further systematic strategies of time-making practices, wherein Algeria became subsumed within France’s postwar reconstruction, as France attempted to cement its position as an important industrial power in the wake of a weakened economy. The rural backcountry, caught between the Tellian and Saharan Atlas Mountains parallel to the coast, was referred to as the maquis, a term for the dense scrub-like vegetation that covered the ground there. With French colonial authority focused in urban centers and colonial agricultural villages, Algerians maintained a certain level of autonomy in the maquis. As the war of liberation intensified in the 1950s, however, this more remote and rural territory became especially contested as the Algerian resistance continued to organize in these villages and the French aimed to expand their administrative control there.19

Domestic Efficiencies

The reorganization of domestic structures in rural Algeria served to integrate the rural population into the network of industrial plants being set up across the territory. As early as 1954, directives were issued to evacuate mountainous areas and construct new camps in strategic zones.20 The French relocated millions of Algerians—some were forced to abandon their villages, others to relinquish their nomadic lifestyles—to camps, overseen by the military. More accessible than the mountains, the plains offered an ideal site for these camps, their flatness a blank slate easily configured according to the occupation’s needs. Whereas the keyword for the Algerian revolutionaries had been dispersion, for the French counterrevolutionaries, it was concentration. The French drastically reorganized the territory, and domestic life in it, into one homogenous plan. The camps were designed according to a military logic: a gridded plan with a “wide linear main street [running] through the flat land to permit immediate access to the camps.”21 Security zones were drawn out within which every movement was administered and controlled, while zones of insecurity, eventually renamed forbidden zones, were erased from the map: no movement was “authorized and tolerated” within them.22 The zoning and displacement of populations was therefore an effort to not only render the territory legible to the French authorities but also to impose the French state’s project onto rural Algeria, drawing a new infrastructural landscape, forcing a productive capitalist clock on variegated Algerian domesticities. The French attempted to reduce Algerian communities and collectivities into recognizable, nuclear units subject to constant surveillance; and to transform domestic life into a militaristic venture valued solely for its productivity and ability to maintain law and order in the camps. In this reorganization of familial structure, French temporality and modernity, both premised on the conviction that time was individualized and linear, was spatialized across the domestic sphere.The relocation was in part a strategy of isolation from “contamination” by the activities of the National Liberation Army (ALN, the armed contingent of the FLN, the nationalist liberation movement), impeding the support and spread of revolutionary momentum.

All in all, 3,740 camps de regroupement were built after 1954.23 The camps were set up near industrial sites, which encompassed the “restoration, reconstruction and new construction of infrastructures, hydraulic facilities, public buildings and other public works.”24 They were predicated on creating and sustaining a labor force. Imposing this extractive framework of industrial production perpetuated French postwar ambitions. France was propelling itself along the path of development and progress through the exploitation of Algerian bodies. On the empire’s periphery, the colony was being molded to serve the metropole, forcibly integrating millions of Algerians into the labor chain. France’s modernity rested on this hinterland. Achieving modernity, the ultimate stage along the French chronology of development, meant redrawing the landscape of its construction. By reconfiguring the Algerian’s life into camps, the French were accelerating their development, if only to be useful to the colonial economy.

Internal clocks: Contesting Modernity through the Female Body?

Strategies of occupation did not stop at the urban or rural scale, but rather seeped into the most intimate levels of society. Women’s bodies became the site of an epistemological battle, one where French postwar societal change was pit against its perceived Algerian opposite, which the French read as traditional, conservative, and backwards. Algerian women thus came to embody Algeria’s broader oppositional temporality, a social framework resistant to change. Embedded in this construct was the idea that women’s liberation in France occurred in stages: French society was progressing, becoming more modern through the changing role of women, and therefore occupied a later stage, a future at which they believed Algerians had not yet arrived. The occupiers posed as White saviors and purveyors of feminist ideals, liberating Algerian women from the yoke of their perceived backwardness. The question of which model guaranteed more rights for women and the extent of women’s agency in this struggle remains beyond the purview of this essay. Instead, what is of interest here is the weaponization of women’s emancipation as a colonial strategy with the aim to accelerate Algerian women to a French level of evolution, to pull them out of their gender quagmire and synchronize them to a French stage of gender emancipation.

While the particular urban structure of the casbah had functioned as a barrier to the French, Algerian women became a vector for other pervasive forms of colonial domination: social workers entered private homes, claiming to teach women their “rights,” and in so doing, familiarized themselves with these intimate, cordoned-off spaces.25 This new access to Algerian women meant the French could convey their emancipatory ideals directly to their target audience. The haïk, a garment worn by some women in Algeria which covered most of their faces, was weaponized by the occupation. The French read the veil as a conservative practice, the opposite of their progressive ideals, and tried to convince women to abandon it, and shed their backwards ways. Propaganda posters spoke to that effect: “Aren’t you pretty? Remove your veil!” Unveiling ceremonies were organized in Algiers, with women publicly renouncing their garbs. As Frantz Fanon relates, the French strategy was clear: Each “haïk pulled off is one more concession, one more woman allowing her own rape by the French colonizer.”26 It therefore became a crucial strategy of the French to qualify the Algerian woman as enslaved and subject to a retrograde patriarchal society, one from which she must be liberated at all costs. Therefore, their dislocation from their own society’s backwardness in favor of the occupier’s modernity points to the French characterization of women’s liberation as fundamentally temporal. Quite cynically, the desynchronization of genders aimed not to guarantee more rights for women, but instead to disrupt Algerian society, and in so doing, to weaken it in the face of the occupation. Indeed, to conquer the woman is to tear her away from her societal fabric, and hence to deconstruct Algerian epistemologies from the inside out. Fanon continues, describing the colonial strategy which fully instrumentalized women, “ayons les femmes et le reste suivra.”27 Algerian society as a whole could therefore be pacified or domesticated precisely through the de-domestication of its women.28

However, this aggression created the potential for resistance. Faced with the colonizer’s offensive on the veil, the colonized responded with the “cult of the veil.”29 Weaponized by both sides, the haïk became more visible, an agent in the liberation struggle, acting as camouflage for the suitcases full of information, documents, money, and weapons that crossed French checkpoints and traveled between caches. Fanon argues that the veil was donned in places where it was not the norm or by women who had never worn it precisely because the French wanted it off. In the face of the occupier-emancipator violently attempting to cast off “tradition” and usher in modernity, the Algerian did the exact opposite, refusing this definition of modernity, the length of its skirts, the cut of its hair. Instead, the rigidity of tradition was imposed, impossible to synchronize or reconcile with a French society undergoing a postwar transformation branded as progressive. The haïk, perceived as anti-modern, was therefore a tool for Algerians to carve out a different temporality for themselves, stagnant in their rigid determination to refuse French paradigms of social development.30 In an act of ultimate resistance, Algerians stopped their watches.

Time as emancipation?

My attempts to parse out the temporalities embedded in the anecdotes above can be read as a series of provocations. Their aim is to expand our vocabulary of occupation. Indeed, time operates at a crucial intersection between an occupation’s epistemic framework and its materiality. To analyze the latter is to unlock an understanding of the former, and vice versa. Yet, as much as I may have attempted to analyze time, it is through living it that it takes on meaning and spatiality. Crossing the checkpoint from Jerusalem into the West Bank, one interruption along the Israeli apartheid wall, funneling thousands of Palestinians who cross through daily, I could not help but be conscious of the Israeli clock, of the need to calibrate my own rhythm to that of the armed soldiers, to make sure I didn’t miss the last bus on Shabbat (Saturday), or that I was crossing during hours of relative quiet and not during an instance of Palestinian protest when the checkpoint transforms into an Israeli shooting range. How to reconcile these humdrum moments with theories on time in the context of ongoing occupation?

And what then is an occupation? Two of its meanings intertwine. It is the assemblage of mundane rituals and routines of an individual—daily occupations. It is also a violent colonial practice imposed through the disruption of the former occupations. In both, however, temporality is at once immanent and operative.

I have argued here that the French occupation attempted to rationalize time as a spatial practice. However, in doing so, it also made space for emancipation in a realm not readily accessible to the occupier. Time in all its complexity exceeds the physical realm: as a biological mechanism, it operates within our body, our very psyche. Intimate to each, it dwells in our consciousness and its perception can be altered. The occupier then, obsessed with the material and bulky paraphernalia of occupation, is rendered helpless: there is a clock whose crown they cannot turn.

-

Zohra Drif, Inside the Battle of Algiers: Memoir of a Woman Freedom Fighter, trans. Andrew Farrand (Washington, DC: Just World Books, 2017), 230–33. ↩

-

National boundaries operated similarly to inter-Algerian checkpoints. The Morice Line, built by the French to physically isolate Algeria from its neighbors from 1957 onward so as to block the passage of resistance fighters from Tunisia and Morocco, respectively, employed similar principles, with the added consequence of cementing national identities but also disrupting the temporal logic of seasonal migration for the considerable nomadic populations of the Sahara. The tension between Algerian movement and French reorganization makes clear that temporalities, as embedded in our territories, are made manifest or spatialized by certain practices or patterns of use. ↩

-

Throughout this essay, I will use Algerian to describe the nonoccupying population of Algeria, despite the problems associated with the term given the diverse nature of the population. French will refer to the occupiers, including the civilian population that moved to Algeria, as well as their children born and raised there. French time, however, refers not to each individual’s immediate sense of time but rather to state-mandated attitudes toward the productive 24-hour cycle. I want to note that I use these terms in full awareness that they do not necessarily reflect the political allegiance of each individual and their implication in the occupation. Rather, the necessity to get past the use of terms such as autochtone and indigenous, as often still used by the French, including in my own education, gives me no choice but to simplify a complex identitarian landscape. ↩

-

See Yacef Saadi, The Battle of Algiers (Algiers: Casbah Editions, 1997), 27. This is a confinement not in the least accepted or recognized by the population, which will establish tactics of resistance that are beyond the scope of this paper. On the contrary, the checkpoint can almost be understood as a recognition by the French that their control can only begin at the threshold between the casbah and the colonial city. ↩

-

Paul A. Jureidini, Casebook on Insurgency and Revolutionary Warfare: 23 Summary Accounts (Washington, DC: Special Operations Research Office, 1964), 258. ↩

-

Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1979). ↩

-

Jureidini, Casebook on Insurgency and Revolutionary Warfare, 258. ↩

-

Giordano Nanni, The Colonisation of Time: Ritual, Routine, and Resistance in the British Empire (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013). ↩

-

Zeynep Çelik, “Colonial/Postcolonial Intersections: Lieux de memoire in Algiers,” Historical Reflections 28, no. 2 (Summer 2022), 143–62. ↩

-

Zeynep Çelik, Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations: Algiers Under French Rule (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 36. ↩

-

Çelik, Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations, 12. ↩

-

Çelik, Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations, 12. ↩

-

Marc Côte, L’Algérie ou l’espace retourné (Paris: Flammarion, 1988), 45. ↩

-

Çelik, Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations, 18–19. ↩

-

Çelik, Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations, 38. ↩

-

Henri Bergson, L’évolution créatrice (Paris: PUF, 2013). ↩

-

Drif, Inside the Battle of Algiers, 336. ↩

-

This can also apply directly to Eyal Weizman’s discussion of Israeli operations in Palestinian refugee camps, in which new logics of circulation were carved out, the camps smoothened for the soldiers’ passage. The Israeli military relied heavily on Deleuze and Guattari’s theories on the interplay of the smooth and striated to qualify and determine the nature of their strategies. Their definition of striated space is constituted of kinds of elements that we can also identify in the Algerian context: the horizontal and the vertical, one fixed, the other mobile. The penetration from the sky, the vertical access according to which the French planned their incursion, therefore confirms the mobility afforded by verticality. ↩

-

Raphaëlle Branche, “Combattants independantistes et société rurale dans l’Algérie colonisée,” 20 & 21 Revue d’Histoire, no. 141 (2019): 113–127. ↩

-

Samia Henni, Architecture of Counterrevolution: The French Army in Northern Algeria (Zürich: GTA Verlag, 2017), 21. ↩

-

Henni, Architecture of Counterrevolution, 30. ↩

-

Henni, Architecture of Counterrevolution, 45. ↩

-

Henni, Architecture of Counterrevolution, 21. ↩

-

Henni, Architecture of Counterrevolution, 90. ↩

-

Frantz Fanon, L’an V de la révolution algérienne (Paris: Editions La Découverte, 2011), 12. ↩

-

Fanon, L’an V de la révolution algérienne, 24. Translation by author. ↩

-

Translates to “if you capture the women, the rest will follow.” Fanon, L’an V de la révolution algérienne, 19. ↩

-

Fanon, L’an V de la révolution algérienne, 21. ↩

-

Fanon, L’an V de la révolution algérienne, 29. Translation by author. ↩

-

This does not mean that Algerian women will not make of this understanding of two different clothing standards a technique of resistance. Dressed in the latest fashion, they will assimilate to French populations when needing to cross the checkpoints on a mission. ↩

Ferial Massoud is a diploma student at the Architectural Association, graduating this month with honors. She considers herself not really French, nor Egyptian, nor American, nor Algerian. She is concerned with the ground as a record of colonial imprints.