At the Isle of Portland, the West Country charm is hard to elude: a small peninsula tied to England by a single beach-lined highway.1 To the south are quaint cottages and lighthouses jutting into the English Channel. North is the seaside town of Weymouth, with idyllic beaches, sailboats, and church spires. Between Weymouth and Portland, however, in the small harbor of Dorset’s Portland Port, floats a rather unexpected barge. This approximately 300-foot long, three-deck, 222-room engineless vessel is clad in alternating gray and red panels. It looks nothing like a water-going ship but rather like a prefabricated housing block that has been laminated onto a hull. Architecturally, that is what it is—a rather typical double-loaded corridor perimeter building with two courtyards, hundreds of austere en suite cabins, laundry, reading, and TV rooms, a canteen, a bar, and a gym. The barge, named the Bibby Stockholm, is an accommodation site enlisted by the British Home Office to house up to 500 single male asylum seekers between the ages of eighteen and sixty-five. Registered in Barbados, the barge was towed from Genoa to Dorset in April 2023 and is run by an Australian agency, its residents men from all over the world seeking asylum in various parts of the UK.2

The Bibby Stockholm was determined to be the cheaper alternative to a hotel. When journalists were allowed on board preoccupancy, bedsheets and towels were pristinely folded on the bunk beds; the kitchen was well stocked with food and beverages under cozy, warm light. One BBC reporter concluded that it is “reasonably comfortable,” while other journalists declared the condition on board “better than some of the hotels currently housing asylum seekers.”3 The Bibby Stockholm’s appearance, spatial arrangement, diverse programs, and maritime character recall a wide spectrum of spaces, from apartment buildings to hotels and migrant shelters, and even to floating prisons. A bizarre amalgamation, it seemed, with the absence of those to be housed, promising to be “better” than existing conditions for recently arrived migrants.

In early August, the first fifteen asylum seekers boarded the barge. At the end of the same month, a fire inspection conducted by the Dorset & Wiltshire Fire Service exposed the barge’s critical safety deficiencies (an insufficient number of fire escapes, fire drills, and issues with air vents4), which led a local NGO to call it the “floating Grenfell.”5 The barge was declared a potential fire hazard, though no additional precautions were taken at the time. In early September, Legionella was found in the water system, and the asylum seekers on board were forced to evacuate for two months. In mid-December 2023, twenty-seven-year-old Albanian asylum seeker Leonard Farruku committed suicide on board, amid a backdrop of diminishing food quality, growing despair, and dwindling supplies.6 The increased number of asylum seekers on board, which reached 300 by March 2024,7 has rendered the living quarters claustrophobic, with “many individuals having to share small, cramped cabins (originally designed for one person), often with people (up to six) they do not know (some of whom spoke a different language to them).”8

The Home Office stated that the various onboard programs were “to minimize [the asylum seekers’] need to leave the site.”9 To leave the barge, even temporarily, is thus difficult by design. If they disembark at any point, asylum seekers are not allowed to move around the port.10 They can only, after passing “airport-style security scans,”11 board buses “to destinations agreed with local agencies” in Weymouth.12 As described by local activist Lynne Hubbard: “The bus comes every hour. Sometimes it might go early, so you might miss it. And there are a limited number of spaces on the bus and there’s only one bus, it will only hold 50 people, so you might not get on that bus. And you can’t leave the port in any other way. So you’re very much confined.”13 Yet this confinement extends beyond the port. With less than £10 per week for expenses and no opportunity for employment, asylum seekers have no means or incentives to leave the barge.14 After the Immigration Act of 2014 and 2016, “everyday bordering” in the UK demands documentation of immigrant status in order to access social services, configuring “doctors, nurses, employers, university staff and landlords as de facto border guards.”15 Confinement thus becomes a form of exclusion, which functions without gates and barbed wires and is made dispersed, quotidian, amorphous, hidden, effectively reinforcing the physical confinement on board.

Documenting the Dadaab refugee complex in East Kenya, architectural historian Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi characterizes refugee camps as “architecture without land.”16 Land for Siddiqi is not merely a surface but also the stratum on and off which one lives, and by its continuity allows the freedom of movement, forming communities and connection with those beyond physical vicinity. For Siddiqi, the architecture of refugee camps delinks from the land, creating a paradox wherein architecture is purposefully constructed to integrate into a site through its isolating disintegration.17 As the physical land is replaced by water on the Bibby Stockholm, land as a layered stratum disappears through exclusionary and confining policies that extend from the sea to the land.

What aggravates the spatial seclusion is the uncertainty of wait time for asylum application. The UK is the sole country in Europe that has no time limit to detain asylum seekers, where liminality is institutionalized as law.18 Asylum seekers are rounded up without knowing the end to their confinement. With the asylum application’s backlog, it could mean several years in waiting.19 The uncertainty of wait time is a form of confinement itself. Furthermore, under “administrative” rather than “criminal” detainment, asylum seekers on board are trapped in the limbo of international law where they have no power to appeal as individuals.20 Giorgio Agamben’s distinction of camp from prison posits that while the latter is an institution within the legal system, camps are only set up in the wake of extraordinary circumstances beyond the scope of the law. Additionally, as an enduring physical structure, the camp materializes the permanence of the state of exception.21 Like many “temporary” expediencies that arose from emergency yet are paradoxically long-lasting (e.g., New York City’s “floating jail,” the Vernon C. Bain Correctional Center, which was meant to offer temporary ease to the penitentiary system but stayed open for over three decades), the camp operates in what Siddiqi calls a “permanent ephemerality,” wherein a promised temporariness justifies a compromised space, forming a collusion between space and time.22 The barge places asylum seekers in an exceptional yet lasting siege, where liminality is violently weaponized, operating in the legal framework between sovereign and international law, the uncertainty of asylum results and its wait time, and the precarious position between land and sea.

The Floating Options

Housing asylum seekers on isolated water vessels is nothing new. When asked in 1995 about a series of barges, including the Bibby Stockholm, docked in Hamburg as migrant housing, activist Frank Eyssen emphasized, “These are not concentration camps. They are not prisons. But there are security guards. And you are floating in the water, isolated from normal city life. They are distinctly unfriendly places.”23 While the UK government refutes the characterization of the Bibby Stockholm as a “floating prison” and tries to downplay its restrictive nature, viewing it solely as a prison also overlooks its complex liminality. It is a persistent physical structure where laws are suspended, and rights, obligations, and roles are subjected to a stifling uncertainty.

A liminal typology as such, “floatels” or “floating options,” can be found abundantly in the recent history of the Bibby Line, a corporation founded in 1807 in Liverpool. While historically a shipping company—one that participated in the Atlantic slave trade and profited from Britain’s colonial effort, from supplying the East India Company and operating cargo and passenger ships to British Burma and Ceylon to transporting troops for the Boer War24—the Bibby Line turned toward maritime accommodation in the early 1980s in the midst of a shrinking freight market.25 Since then, at least seven accommodation barges owned by the Bibby Line were proposed or have taken on diverse programs over water. The Bibby Stockholm, Kalmar, Altona, Challenge, and Progress have been chartered by governments to house asylum seekers in Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden.26 The Bibby Venture and Resolution were chartered by the New York Department of Correction, opened in 1987 off Greenwich Village and 1988 off the Lower East Side, respectively, as jail barges, until their closure in 1992.27 The Bibby Resolution was later bought by the UK’s Prison Service in 1997 and taken to Portland Harbor as a floating prison, rechristened the HM Prison Weare.28

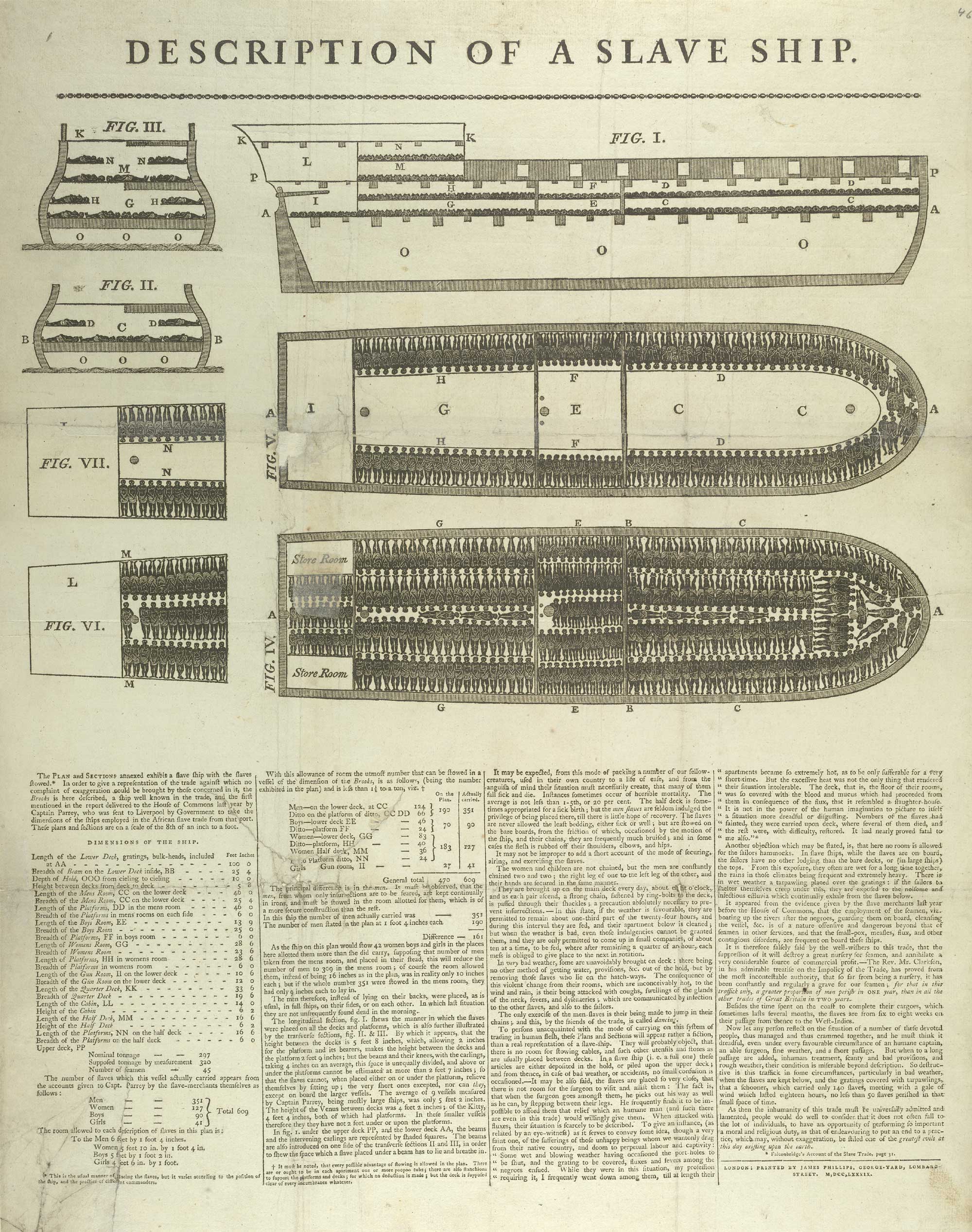

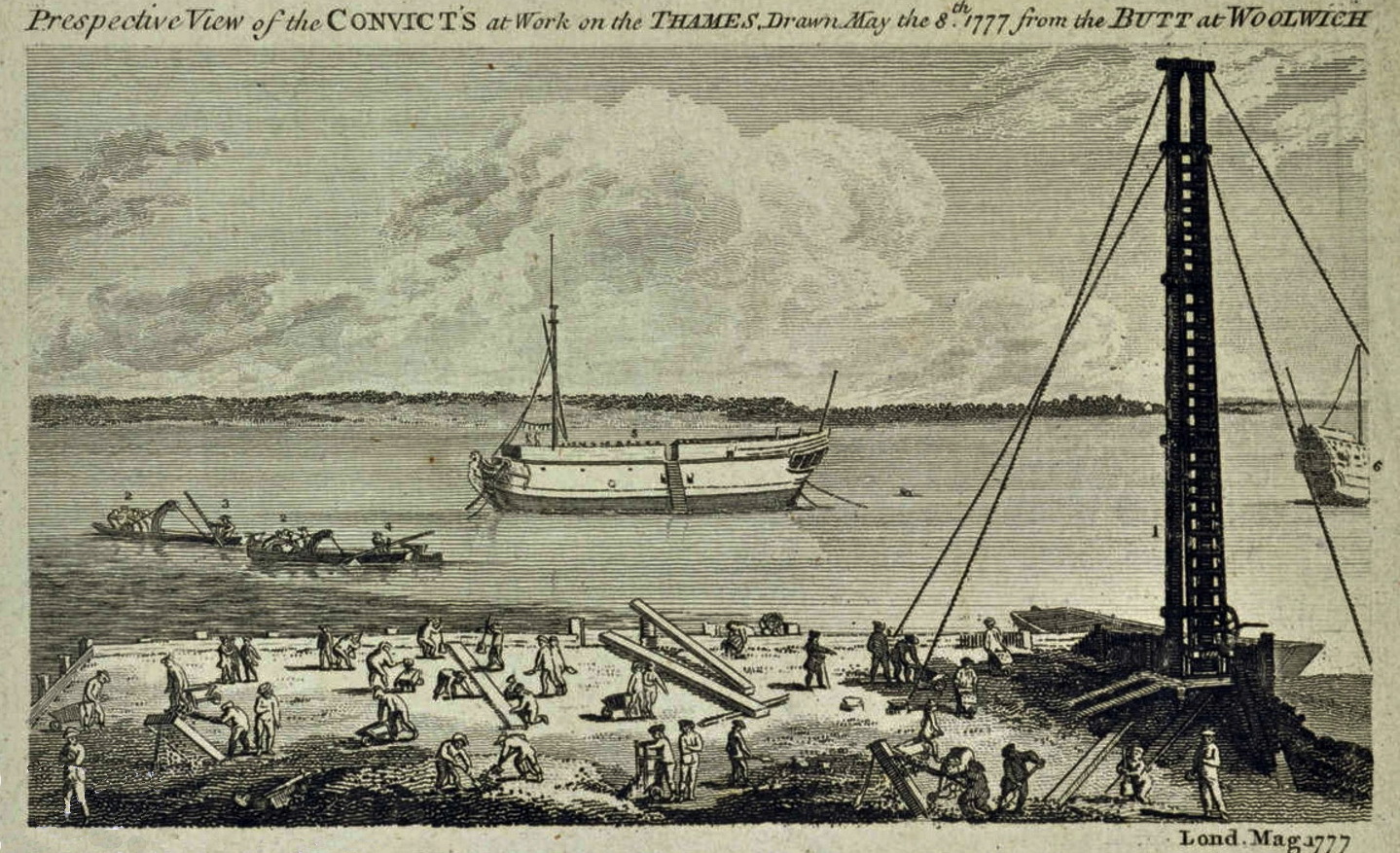

The Bibby Line is just one story in Britain’s maritime history of employing water vessels as an apparatus of dehumanization. The English slave ship is the conspicuous icon that served as an engine of modernity at the cost of mass subjugation, incarceration, and murder. The cruelty of the Middle Passage was rendered clear in spatial terms: in 1788, British abolitionists commissioned a drawing that illustrated (in plan and in section) how enslaved people were held captive in the infamous slave ship Brooks. These drawings shocked the British public and spread across the Atlantic.29 At the time, decommissioned ships were repurposed as prisons, known as “prison hulks.” First introduced in 1776 along the Thames, the hulks detained prisoners who were made to dredge the river, and soon propagated to other parts of the British empire throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.30 With the exception of the Dunkirk from 1784 to 1791 and Narcissus and Heroine in the 1820s,31 hulks detained male prisoners from the most dangerous criminals to boys under the age of ten.32 Hulk mortality rates in the eighteenth century were astonishingly high; during the first twenty months of operation, 150 of the 600 prisoners died.33

With their brutality captured in Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations, the hulks are compared to the latter-day “floating options” whenever such a proposal is on the table.34 In 1987, Margaret Thatcher’s government leased the ferry Earl William to house 120 African and Asian asylum seekers at Harwich, including women and children. Amid deplorable sanitary conditions on board, asylum seekers initiated hunger strikes and sought the sympathy of the British public. Their impassioned pleas went unanswered until a hurricane that October, when the ferry broke free from its mooring in the storm, colliding with multiple barges and narrowly avoiding a shipwreck. After the rescue, asylum seekers were granted temporary admission to the UK.35 As an advocate for the welfare of those on board commented: “For months we have been campaigning for their release… [N]ow the furious hand of nature has replied.”36 Despite the attempts to use these “floating options” to tame the sea, as if it is immobile and fixed, the sea breaks free as such efforts crumble in the face of the very materiality they sought to overcome.

To the Home Office, the public is forgetful enough that the failure and cruelty of the past can be recast as success and kindness. The Bibby Stockholm was once deployed as an accommodation barge for asylum seekers and workers in the Netherlands, Germany, and the UK. It was even proposed as student housing in Ireland.37 The UK government eagerly embraces this history to justify its ongoing operation: “[barges and other alternatives to hotels] are cheaper and more manageable for communities, as our European neighbours are also doing… The Bibby Stockholm has safely and comfortably housed workers from various industries, including shipyard workers, construction workers and offshore construction workers over the years.”38 The same narrative was adopted by the Bibby Line, an integral partner of the “prison industrial complex,” as early as 1999 to defend the Bibby Progress and Goteborg as asylum seeker housing in Liverpool by citing their previous function “in the Netherlands and by US naval personnel in France.”39

Like the barge’s façade that desperately tries to conjure up a picture of apartment-like domesticity, this normalizing narrative covers up a long chain of violent records. During its operation in Rotterdam as a detention facility for asylum seekers, Algerian national Rachid Abdelsalam died due to inadequate medical treatment and ignored cries for help.40 An undercover journalist revealed in 2006 the dismal living conditions, lack of safety precautions, and human rights abuses that led him to conclude that the Bibby Stockholm was a “floating powder keg.”41 The so-called success of past Bibby Stockholms works to secure the existence of future ones. The barge’s history of housing asylum seekers, particularly by a self-occidentalizing complacency (“our European neighbours”), normalizes the practice, outsources the moral questions, and diverts further inquiries from concrete suffering and violence. In this narrative, space alone is presented as the legitimizing factor: by virtue of occupying the same “space,” even with doubled occupancy and indeterminate wait times, the “floating option” becomes, purportedly, humane.

Outside, Offshore, By-the-Sea

If we’re to examine these “floating options”—prisons, refugee camps, military barracks, and school and factory dormitories—through a Foucauldian lens, we can further visualize the disciplinary apparatus as intimately tied to maritime imagination. In Madness and Civilization, Foucault revisits the historical practice in Medieval Europe where “the mad” were dispatched onto “ships of fools,” embarking on a maritime exile into the unpredictable sea—“that great uncertainty that is external to everything.”42 Here, the stultifera navis, consigning “the mad” to the sea, is an act of simultaneous exclusion and cure, confining and treating them through the purifying power of water.43 This dual purpose of a maritime space is later echoed in Discipline and Punish as the naval hospital of a port city, which is tasked at once with treating diseases and controlling the “swarming mass” teeming at the threshold between land and sea.44 The synchronous pursuit of protection and control is identified as a paradigmatic logic underpinning refugee camps.45 On the Bibby Stockholm, this is dually evinced in the Home Office’s narrative of security, where it vacillates between care and surveillance, ambiguously (not) defining who should be protected, and why:

The Bibby Stockholm provides non-detained accommodation for single adult male asylum seekers aged 18 to 65 who would otherwise be destitute… Every individual on the vessel will have been screened against policing and immigration databases. They will have had their fingerprints and identities recorded prior to going aboard… Those on the vessel are not detained, so there is no curfew. However, if an asylum seeker is late returning to the vessel, the team will make a call to ascertain their whereabouts.46

The “everyday bordering” makes possible a form of control where asylum seekers could be confined beyond physical enclosure. The shift in the paradigm of control is evident in Foucault’s 1982 campaign for Vietnamese boat people seeking asylum on Australian shores, where he remarked that refugees are the first people “imprisoned outside.”47 The shore as the oceanic border that takes the sea—supposedly an unbound vastness—as an imprisoning “outside” that encloses an insular island, is deep-seated in the British imagination. As captured by Shakespeare: “This precious stone set in the silver sea,/Which serves it in the office of a wall/Or as a moat defensive to a house,/Against the envy of less happier lands.”48 Or, as an audience member at the televised debate between Rishi Sunak and Keir Starmer put it more plainly: “We’re an island, why can’t we easily close our borders?”49The exclusionary “outside”—the sea—is thus transformed, with naval architecture, as the oceanic “offshore,” a racialized space that removes undesirable populations while politicizing the shore to maintain the myth of land’s purity.50 Viewed this way, offshore is the colonial strategy linking the Bibby Stockholm to other proposals for housing asylum seekers, such as on North Sea oil rigs or in overseas territories like St. Helena.51 The ongoing Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Bill proposes to deport asylum seekers to the central African nation 7,000 kilometers away.52 And Boris Johnson’s government suggested “floating wall, sea barrier, or even wave machines in the middle of the English Channel” to stop small inflatable boats from reaching British waters.53 If barges are only timid attempts to tame the sea that is endlessly moving and boundless, these outlandish proposals evince an annihilation fantasy pushed to a megalomaniacal extreme, where the sea becomes a defenseless pond to be severed and manipulated and human life trivial specks.

Brexit and COVID-19 have led to increasingly stringent travel restrictions on lorries, the previously favored migrant route to the British Isles.54 In 2020, three specific policies added restrictions to lorries across the English Channel: the coming into effect of Brexit and the disruption due to COVID-19 travel restrictions.55 From 2020, the number of those seeking asylum via small-boat travel across the Channel in rose steadily, from 1,843 in 2019 to 45,755 in 2022.56 However, there are no legal means to apply for asylum outside the UK other than predetermined government schemes,57 and statistically, asylum seekers who cross the Channel are denied asylum in the European Union.58 Without providing safe routes to asylum, Rishi Sunak’s government imposes new immigration laws that weaponize the risk of irregular maritime travel under the banner “stop the boats,” disregarding the fact that the policies themselves only worsen the humanitarian crisis. This maritime space is reproduced as bordering for future asylum seekers and punishment for those who have made it to Britain’s shores. This leans into the optics of the barge, particularly its isolation, lending “deliberate deterrent effects”59 to eradicate further influxes of newcomers. Ironically, Sunak’s solution to “stop the boats” is simply more boats. The carceral nature of the barge, the psychological trauma of the sea and the shipwreck, the pipeline from floating detention to offshore banishment are summed up in the words of a current asylum seeker on the Bibby Stockholm: “We are terrified they will unlock the boat and sail it away to Rwanda.”60

For now, the Bibby Stockholm is stationary, docked at a port, surrounded with barbed wire and heavily patrolled by Dorset Police. Berthed exactly at the shore, its isolation is exacting, enclosing those aboard in a thickened coastline. Its location in relation to the sea, following the English toponym “by-the-Sea,” is a compound suffix that qualifies its spatial precision and apologizes for its littoral otherness. With the population of a small town, “Stockholm-by-the-Sea” does not invoke the sea for its picturesque aesthetics as its quaint Dorset neighbors do but is rather in a state of siege, prevented from reaching land, in quarantine, as the original meaning of the word: “period a ship suspected of carrying contagious disease is kept in isolation.”61 Its power—control—exerted as a precise point of entry delineates, in the eyes of the Home Office and its supporters, who is worthy of freedom—in its expanse of forms. Echoes again from Foucault’s ship of fools:

The madman’s voyage is at once a rigorous division and an absolute Passage. In one sense, it simply develops, across a half-real, half-imaginary geography, the madman’s liminal position on the horizon of medieval concern—a position symbolized and made real at the same time by the madman’s privilege of being confined within the city gates: his exclusion must enclose him; if he cannot and must not have another prison than the threshold itself, he is kept at the point of passage.62 (Emphasis in original.)

“By-the-Sea” is neither “offshore” or “onshore.” As a spatial strategy, it is a precise suspension at the shore. However, the shore as a linear cusp where the land meets exactly the end of incessant waves is only a geometric abstraction. As such, the shoreline must be precisely and conceptually constructed. “By the Sea” is thus a proximate space defined by pointing a finger from land (“there, by the sea!”), a spatial propinquity that ensures visual surveillance—the ability to be “overseen” at the point of passage. Isabel Hofmeyr depicted this suspension at the maritime border in her study of customs houses in colonial South Africa. In the port cities, the colonial government oversees the process of “landing,” the inspection of the passage of goods, books, and people, wielding authority over what and who is deemed worthy of entry. Against this historical backdrop, the term “landed immigrant” is assigned to individuals considered admissible by the colonial government, granting them residency, incorporating them onto land and away from the perilous oceanic space.63 With the exertion of maritime power, “hydrocolonialism” transports commodities and bodies across oceans. It turns this power into an identitarian force through the ceremonial act of “landing.” “By-the-Sea” is the liminal status that awaits “landing.” Instead of being imprisoned “outside” or “offshore,” one is pinned at the limit, under the mistrustful and scrutinizing gaze from land, between inside and outside, between detainment and exile, between land and sea.

“Spatial Revolutions”

Hofmeyr’s “hydrocolonialism” reveals the inherent contradiction of Britain as an oceanic power. If the intrinsic attribute of a maritime power exercises dominance over the sea—the outward assertion of its own rule and law over water—what accounts for the constant mythification and the jealous, inward guarding of land? What feeds the perennial anxiety over the land’s purity and the invocation of insular imagination defined by the coast and the seashore, and the physical and psychic delineations of “inside/outside,” “onshore/offshore,” “landed immigrant/unlanded alien”?

Some traces can be found in Carl Schmitt’s Land and Sea, in which Schmitt identified Britain’s world domination as initiating a “spatial revolution.” According to the German jurist, the centuries-long colonial impetus rejects a singular spatial enclave, where “England” ceases to exist as an island—turning “into a part of the sea, into a ship, or, even more significantly, into a fish.”64 This fish—the England of Leviathan—becomes the agent and the medium brutishly monopolizing currents and connections. In this light, Britain’s spatial revolution is one that claims the sea as the new land—christened by Schmitt as “space”—that emancipated humans from land’s limit and from being provincial “land-dwellers.”

Schmitt’s opening remark that “the human is a land-being, a land-dweller”65 and his later claim that “world history is a history of land-appropriations”66 shed light on the expansionist nature of his spatial revolutions, which is ultimately rooted in the territorial metaphor of land. The “landedness” of his maritime space chimes with National Socialism ideology: his essentialist terms of land and human nature become the theoretical basis to exclude Jewry from humanity as landless pariahs.67 Carl Schmitt’s space thus effortlessly metamorphoses into Giorgio Agamben’s camp, or, again in Siddiqi’s words, “architecture without land.”68 The expansion of modalities of colonial containment from land to sea via Britain’s spatial revolution hence necessitates new camps—the offshore, and its maritime apparatus of dispossession, imprisonment, and persecution that confers humanity to those who control space (now both land and sea) and dehumanize the rest. This new maritime apparatus is demonstrated today in the “Pacific Solution” in Australia, barges and offshore detention in the UK, “floating Guantánamos” of the US Coast Guard, the jail barge in the South Bronx, “floating barriers” in the Pas-de-Calais and the Rio Grande… Inscribing the surface of water as the surface of soil, the modus operandi over land and sea, as well as all the aggrandizing pretenses of modernity, collapse into the primeval paradigm of appropriation, conquest, and subjugation.

This planetary enclosure of the sea, a dystopian Mare Clausum, was limited by the innumerable movements of resistance from the minuscule to the global.69 Among the myriads of projects of resistance and solidarity, many have been heedful of the spatial nature of the ocean and masterfully incorporated it into their methods of activism. Forensic Architecture’s “Left to Die Boat” report uses oceanographic mapping to reveal the intentional hostility toward cross-Mediterranean migrants from European nations, where architectural training of graphic representations is mobilized to render visible the oceanic obscurity through the increasingly advanced digital armature.70 Women on Waves, a Dutch NGO, offers nonsurgical abortion in international waters to eligible women from countries where abortion is restricted.71 As national laws rule over fixed geographical jurisdiction, spatial thinking makes international waters a domain of freedom and resistance through a mobile, portable sovereignty. Like the abolitionists’ drawings of the slave ship Brooks, the seemingly totalizing “strategy” urgently demands the countering “tactics” that exploit its own loopholes and vulnerabilities. Enclosure and openings, fixation and mobility, and indeed, land and sea are never just spatial or geographical metaphors but must lead the practitioners in these domains into innovations that engage with them head on.

Epilogue: The Planetary Family Resemblance

Hannah Arendt penned the essay “We Refugees” during her exile in New York as a Jewish émigré in 1943, which she began with: “In the first place, we don’t like to be called refugees.”72 Surrogates of “refugees” or “migrants,” however, have been burdened with names of boats, inscribing one linguistically at the journey, the point of passage: the “Windrush generation” of the UK, the “Marielitos” and “Balseros” from the Caribbean, the “Boat People” from Vietnam and Haiti. How can one debark from a boat that one is forever branded with?73 Would Sunak’s government inscribe another generation with the “floating options”?

If there is a “Bibby Stockholm” generation, its members remain a mystery. Achille Mbembe pointed out in Necropolitics that the routine form of exclusion is to strip one of a name, and thus a name-bearing body and face.74 The Home Office does not disclose the demographics of asylum seekers on board, other than the fact that they are single, male, and between ages eighteen and sixty-five.75 And this anonymity has real repercussions—the caseworkers who read asylum applications are off-site, and have no face-to-face interaction with the applicants.76 What seems to protect simultaneously controls through categorization, reification, into a homogenous group of undifferentiation. That is, until death. Again, the asylum seeker who committed suicide in mid-December was named Leonard Farruku. He was twenty-seven years old and from Albania. He will be remembered by family and friends as a gifted and ambitious accordionist.77

Against the reification that renders people into anonymous categories, Achille Mbembe proposes an “ethics of the passerby.” The passerby recognizes her own face in the face of others, rendering clear a nascent face of humanity. To be a passerby is to refute, through journeying, Schmitt’s essentialist link between “blood and soil,” to recognize the face and fate of one’s own in that of those whose faces are erased and whose fate is foreclosed. For Mbembe, the quintessential passerby was Frantz Fanon— “Born in Martinique, passing through France, he tied his fate to Algeria’s very own.”78 The labor of passing makes self-identification not a naïve embrace of the “unanimist illusion” but one that was attained by action.

The dedication of the local activists has made it possible for asylum seekers to form links and make their voice heard. Resistance against “by-the-Sea” employs tactics that exploit the visual continuity and the limited physical freedom allowed to the migrants, challenging the Home Office’s effort to isolate them. Local groups, including the Portland Global Friendship Group and Stand Up Against Racism Dorset, have been organizing protests at the port, distributing toiletries and information for support groups.79 In October 2023 and May 2024, groups of activists have mobilized to stop buses from carrying asylum seekers to the barge. The visibility of the Bibby Stockholm has resulted in sustained media attention and received continued condemnation from charities and activist groups.80 The passengers on the Bibby Stockholm are intentionally rendered faceless, but shouldn’t this become the basis for solidarity? To resist facelessness, perhaps we can respond with Mbembe’s humanist physiognomy, a planetary “family resemblance.”

-

Special thanks to Ana María Léon Crespo, whose seminar in the fall of 2023 and sustained support were indispensable to the development of this essay. I would also like to thank Isabelle Kirkham-Lewitt, Taylor K. Miller, and Melis Uğurlu for their generous help and insightful comments, as well as colleagues and teachers at the GSD and beyond for their intellectual guidance. ↩

-

Diane Taylor, “Asylum Seekers to Be Housed on Dorset Barge, Home Office Confirms,” The Guardian, April 5, 2023, link. ↩

-

Dan Johnson and Michael Sheils McNamee, “Inside Bibby Stockholm: On Board Barge Housing Asylum Seekers,” BBC, August 7, 2023, link. ↩

-

Rajeev Syal and Diane Taylor, “Fire Safety Report Demanded Five Changes on Bibby Stockholm,” The Guardian, August 31, 2023, link. ↩

-

“Bibby Stockholm: A Floating Grenfell?” One Life to Live, July 31, 2023, link. ↩

-

Diane Taylor and Rajeev Syal, “Growing Despair of Asylum Seekers on Bibby Stockholm over Living Conditions,” The Guardian, December 13, 2023, link. ↩

-

“Bibby Stockholm: Update from the Multi-Agency Forum March 2024,” Dorset Council, March 19, 2024, link. ↩

-

Dame Diana Johnson, quoted in Jennifer Scott, “Bibby Stockholm: ‘Claustrophobic’ Asylum Seeker Barge Risks Human Rights Breach, MPs Warn,” Sky News, February 2, 2024, link. ↩

-

“Portland Port: Fact Sheet,” Promotional Material, Home Office, last modified December 13, 2023, link. ↩

-

“Portland Port Update - Setting Out the Facts,” Portland Port, May 23, 2023, link. ↩

-

Johnson and McNamee, “Inside Bibby Stockholm.” ↩

-

“Portland Port: Fact Sheet.” ↩

-

Lynne Hubbard, quoted in Bethany Dawson, “‘Wingless Birds’: Life Aboard Britain’s Controversial Bibby Stockholm Asylum Barge,” Politico, December 7, 2023. ↩

-

“An Open Letter to Bibby Marine,” Refugee Council, July 4, 2023, link. ↩

-

Yasmin Ibrahim, Migrants and Refugees at UK Borders: Hostility and “Unmaking” the Human (London: Routledge, 2022), 19, 23. ↩

-

Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi, Architecture of Migration: The Dadaab Refugee Camps and Humanitarian Settlement (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2024), 102, 172. ↩

-

Siddiqi, Architecture of Migration, 102. ↩

-

“Scared, Confused, Alone: The Stark Truth Behind Immigration Detention,” British Red Cross, last updated June 17, 2024, link. ↩

-

The Refugee Council reports that by the end of 2023, 128,786 people were waiting for an initial decision on their asylum claim, and 65 percent of them (51,228) have been waiting for more than six months. A more detailed breakdown shows that as of June 2022, 122,206 were waiting for an initial decision, of whom 32,981 have waited for less than six months, 38,036 have been waiting between six months and a year, 40,913 have been waiting between one and three years, 9,551 have been waiting between three and five years, and 725 have been waiting for more than five years. See “Top Facts from the Latest Statistics on Refugees and People Seeking Asylum,” Refugee Council, February 29, 2024, link; “New Figures Reveal Scale of Asylum Backlog Crisis,” Refugee Council, November 14, 2022, link. See also Joe Tyler-Todd, Georgina Sturge, and CJ McKinney, “Delays to Processing Asylum Claims in the UK,” Research Briefing, House of Commons Library, March 20, 2023, link. ↩

-

Alfred de Zayas, “Human Rights and Indefinite Detention,” International Review of the Red Cross 87, no. 857 (March 2005): 18, 31. ↩

-

Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998), 20, 120–80. ↩

-

Siddiqi, Architecture of Migration, 200. On the collusion of space and time, see Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi and Somayeh Chitchian, “To Shelter in Place for a Time Beyond,” in Making Home(s) in Displacement: Critical Reflections on a Spatial Practice, ed. Luce Beeckmans, Alessandra Gola, Ashika Singh, and Hilde Heynen (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2022), 48. ↩

-

Nathaniel C. Nash, “Hamburg Journal: Off a German Shore, Their Lives Lie at Anchor,” New York Times, September 11, 1995, link. ↩

-

In the Refugee Council’s open letter, three voyages of slave trading were identified; see Refugee Council, “Open Letter.” In a 1990 commissioned history of the company, only one was acknowledged. See Nigel Watson, The Bibby Line 1807–1990: A Story of Wars, Booms and Slumps (London: James & James, 1990), 10. For the company’s other involvement in colonialism, see Watson, The Bibby Line, 14–34. See also E. W. Paget-Tomlinson, The History of the Bibby Line (Liverpool: Bibby Line Limited, 1970), 4–58. ↩

-

Watson, The Bibby Line, 53–63. ↩

-

Nash, “Hamburg Journal”; “Allemagne: Après l’espoir, la désillusion des foyers d’urgence,” Le Monde, June 20, 2002, link; “Vergangenheit kehrt wieder,” Die Tageszeitung, June 21, 2014, link; Ronald Faux, “Barge Could Become Jail for 400 inmates; The Bibby Progress,” The Times, September 9, 1993, link; Alan Travis, “Private Barge Plan for Asylum Seekers,” The Guardian, December 18, 1999, link. ↩

-

Selwyn Raab, “2 Jail Barges to Be Closed and Removed: Facing a Federal Suit, New York City Yields,” New York Times, February 15, 1992, link; “First Group of Inmates Moves to Prison Barge,” New York Times, March 7, 1989, link. ↩

-

Steven Morris, “Britain’s Only Prison Ship Ends Up on the Beach,” The Guardian, August 11, 2005, link. ↩

-

Robert Chambers, The Book of Days: A Miscellany of Popular Antiquities in Connection with the Calendar, Including Anecdote, Biography, & History, Curiosities of Literature, and Oddities of Human Life and Character, vol. 2 (London: W. & R. Chambers, 1864), 67. ↩

-

Anna McKay, “Floating Hell: The Brutal History of Prison Hulks,” BBC History Magazine, October 27, 2022. ↩

-

Robin Evans, The Fabrication of Virtue: English Prison Architecture, 1750–1840 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 120, 227, 247. ↩

-

See, for example, Ronald Faux’s 1993 report for The Times, “Bibby Progress”; Alan Travis’s 1999 report for The Guardian, “Private Barge Plan for Asylum Seekers”; and Anna McKay’s 2023 op-ed on the Bibby Stockholm in Anna McKay, “Why Does the Tory Plan to House Asylum Seekers on Barges Sound Dickensian? Because It Is,” The Guardian, April 8, 2023, link. ↩

-

Felix Bazelgette and the New Internationalist Team, “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea,” New Internationalist Magazine, November 27, 2018, link. ↩

-

Vairamattu Varadakumar, quoted in David Rose, “ ‘Furious Hand of Nature’ Reaches Out to the Tamils,” The Guardian, October 17, 1987, link. ↩

-

Lorna Siggins, “Floating Option Put Forward to House Students,” Irish Times, August 23, 2017,

link. ↩ -

Home Office, “Fact Sheet.” ↩

-

Travis, “Private Barge Plan for Asylum Seekers.” ↩

-

Robina Qureshi, “Mired in Controversy, the Bibby Stockholm Asylum Barge Is a ‘Potential Deathtrap,’” Positive Action in Housing, August 3, 2023, link. ↩

-

Robert van de Griend, “Undercover op de illegalenboot,” Vrij Nederland, April 1, 2006, link. ↩

-

Michel Foucault, Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Vintage Books, 1988), 10–11. ↩

-

Foucault, Madness and Civilization, 10. ↩

-

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1995), 144. ↩

-

See Michel Agier, Managing the Undesirables: Refugee Camps and Humanitarian Government, trans. David Fernbach (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2011), 4; See also Andrew Herscher, Displacements: Architecture and Refugee (London: Sternberg Press, 2017), 78. ↩

-

Home Office, “Fact Sheet.” ↩

-

Agier, Managing the Undesirables, 181, 240n8. ↩

-

William Shakespeare, Richard II, ed. Jacob Abbott (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1901), 29–30. ↩

-

BBC News, “UK General Election: Sunak and Starmer Clash over Borders, Tax, and Gender in TV Debate,” YouTube, June 26, 2024, link. ↩

-

See Paul Gilroy, “‘Where every breeze speaks of courage and liberty’: Offshore Humanism and Marine Xenology, or, Racism and the Problem of Critique at Sea Level,” Antipode 50, no. 1 (May 2017): 4, 18. ↩

-

Davies et al., “Channel Crossings,” 2319. ↩

-

In 2022, Boris Johnson’s government initiated the “UK and Rwanda Migration and Economic Development Partnership,” simply known as the “Rwanda Asylum Scheme,” that will allow the UK to deport asylum seekers to wait for asylum processing or be resettled in Rwanda. The plan was struck down in court. In late 2023, the “Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Bill” was introduced in Parliament and passed in April; that bill recognizes the safety of Rwanda as a third country for asylum seekers. See “Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Bill: Factsheet,” Policy Paper, Home Office, updated April 25, 2024, link. ↩

-

Davies et al., “Channel Crossings,” 2317. ↩

-

Ibrahim, Migrants and Refugees at UK Borders, 75. ↩

-

Ibrahim, Migrants and Refugees at UK Borders, 75, 78, 81. ↩

-

It should be noted that, against the alarmist rhetoric, asylum seekers only make up a tiny portion of immigrants to the UK each year. Even with the overall decrease of other forms of immigration during COVID, asylum seekers still were only 12 percent of all immigrants in 2020. “People Crossing the English Channel in Small Boats,” Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, July 21, 2023, link; Georgina Sturge, “Asylum Statistics,” House of Commons Library, Research Briefing SN01403, May 24, 2024, link. ↩

-

“Asylum and Refugee Resettlement in the UK,” Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, last modified January 27, 2023, link. ↩

-

Davies et al., “Channel Crossings,” 2311. ↩

-

Aletha Adu, “Home Office to Announce Barge as Accommodation for Asylum Seekers,” The Guardian, April 3, 2023, link. The National Audit Office (NAO) reported in March 2024 that the use of irregular accommodation, including military barracks and barges for asylum seekers, has cost £46 million more for asylum seekers, refuting the Home Office’s claim. See “Alternative Asylum Accommodation Will Cost More Than Hotels,” National Audit Office, March 20, 2024, link. ↩

-

Diane Taylor, “More Than 60 Charities Demand Closure of Bibby Stockholm Barge,” The Guardian, December 15, 2023, link. ↩

-

“Etymology of Quarantine,” Online Etymology Dictionary, link. ↩

-

Foucault, Madness and Civilization, 11. ↩

-

Isabel Hofmeyr, Dockside Reading: Hydrocolonialism and the Custom House (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 5–20. ↩

-

Carl Schmitt, Land and Sea: A World-Historical Meditation, eds. Russell A. Berman and Samuel Garrett Zeitlin, trans. Samuel Garrett Zeitlin (Candor, NY: Telos Press Publishing, 2015), 79. ↩

-

Schmitt, Land and Sea, 5. ↩

-

Schmitt, Land and Sea, 63. ↩

-

Schmitt, Land and Sea, 5. ↩

-

Siddiqi, Architecture of Migration, 102, 172; Agamben, Homo Sacer, 20, 120–80. ↩

-

For examples of actions of solidarity over the ocean, see the detailed report of Amnesty International, Behrouz Boochani’s journey and activism in Nauru, and Proactiva Open Arms, which rescues migrants traveling on irregular vessels, to name a few. ↩

-

See Charles Heller, Lorenzo Pezzani, and SITU Research, “Left-to-Die Boat,” in Forensis: The Architecture of Public Truth, ed. Forensic Architecture (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014), 637–56. See also Charles Heller and Lorenzo Pezzani, “Liquid Traces: Investigating the Deaths of Migrants at the EU’s Maritime Frontier,” in Forensis: The Architecture of Public Truth, 657–84. ↩

-

For a general narrative of the Women on Waves campaign, see “Campaigns,” Women on Waves, link; for a detailed narrative of their campaign over water in Poland and Portugal, see Rebecca Gomperts, Women on Waves: Poland (Amsterdam: Women on Waves, 2003); and Gomperts, Women on Waves: Portugal (Amsterdam: Women on Waves, 2003). ↩

-

Hannah Arendt, “We Refugees,” in Hannah Arendt, The Jewish Writings, eds. Jerome Kohn and Ron H. Feldman (New York: Schocken Books, 2007), 264. ↩

-

For a more detailed discussion on identity and the ship in the context of Haiti, see Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 45–52. ↩

-

Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 140. ↩

-

Home Office, “Fact Sheet.” ↩

-

Ibrahim, Migrants and Refugees at UK Borders, 24. ↩

-

Diane Taylor, “Family of Man Found Dead on Bibby Stockholm Turn to Crowdfunding to Repatriate His Body,” The Guardian, January 2, 2024, link. ↩

-

Mbembe, Necropolitics, 184–88. Glissant provides a similar estimation of Fanon’s journey through the concept of errantry. See Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 18. ↩

-

Johnson and McNamee, “Inside Bibby Stockholm.” ↩

-

Steven Morris and Diane Taylor, “Chaotic scenes as first asylum seekers return to Bibby Stockholm barge,” The Guardian, October 19th, 2023, link. ↩

Yifei Zhang is a master’s student in Design Studies at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. Originally from Zhengzhou, China, Yifei received his BArch and BA in Architecture and French Studies (cum laude, Tau Sigma Delta) from Rice University. At Harvard, Yifei works as a research assistant and as an editorial assistant at CAMLab. Yifei is interested in the intersection between architecture, urban history, and the material culture of the sea.