Yes, everybody will have to be compromised in the fight for the common good. No one has clean hands; there are no innocents and no onlookers. We all have dirty hands; we are all soiling them in the swamps of our country and in the terrifying emptiness of our brains. Every onlooker is either a coward or a traitor.

—Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth1

Colonizers write about flowers.

I tell you about children throwing rocks at Israeli tanks

seconds before becoming daisies.

I want to be like those poets who care about the moon.

Palestinians don’t see the moon from jail cells and prisons.

—Noor Hindi, “Fuck your Lecture on Craft. My People are Dying”2

Critical architectural theory

Architectural theory without its critical component—that is, without a focus on life and on positive social transformation—has been at best a “move to innocence” that seeks an apolitical neutrality and at worst a component of orchestrated and intentional colonial violence.3 To define architectural theory as a critical theory is not only to describe with a broad range of specificities the conditions, phenomena, spaces, materials, and economies that make this or that built or speculative project but to consider the policies, legislation, occupation, displacement, toxicity, and destruction related to them.4

Max Horkheimer explains in his definition of critical theory how the “Marxist categories of class, exploitation, surplus value, profit, pauperization, and breakdown are elements in a conceptual whole, and the meaning of this whole is to be sought not in the preservation of contemporary society but in its transformation into the right kind of society.”5 In this process of positive transformation, critical architectural theories must be willing to engage with the materializations of the colonial destruction of “reasonable conditions for life,” as manifested in the legacies of redlining in the US, plantation cartographies of the Caribbean, apartheid spatial planning in South Africa, and the implementation of Bauhaus principles in the Zionist occupation of Jaffa for the creation of the “white city” of Tel Aviv.6

If a theory is critical inasmuch as it seeks to address the limits, constraints, and forms of oppression keeping humans from living free, architectural theory can only be critical once it stops turning away from escalating militarization, the expansion of the prison-industrial complex, class subjugation, and the materialization of racialized, casteist, and gendered repression. In short, critical theories of architecture are concerned with human emancipation.

However, many disingenuous moves to innocence of conventional Western architectural theory continue to flare up in curricula across architecture schools, in the professionalization of unethical colonial practices, and in the work of architectural theorists who refuse to engage with the critical questions of our times, from the anthologies edited by Kate Nesbitt and K. Michael Hays in the 1990s and 2000s, to the more recent works by Pier Paolo Tamburelli, Pier Vittorio Aureli, Patrik Schumacher, Markus Breitschmid, and Mario Carpo, to name a few.7

While an architectural theory that avoids confronting the role of architecture in ecocides and genocides may focus on decontextualized ideas about form, authorship, technology, program, materiality, and phenomenology, a critical theory of architecture would be influenced by what Edward W. Said identified as the “intellectual’s consciousness.”8 Borrowing Said’s words “in a spirit of opposition, rather than in accommodation,” these critical theories of architecture would be able to “dissent against the status quo at a time when the struggle on behalf of underrepresented and disadvantaged groups seems so unfairly weighted against them.”9

Conventional forms of theory think of architecture through Louis Kahn’s old aphorism, “You say to a brick, ‘What do you want, brick?’ And brick says to you, ‘I like an arch.’”10 A critical theory of architecture that demands more engagement with the world than mere questions about form or craft would consider who made the brick, how it was funded, and from which land it was extracted. A critical approach would also ask: What oppressive or liberatory structure or action is this brick going to be a part of, will the brick be launched at an invading military’s tank, or, in the spirit of 1968, would it be thrown at the police as the slogan “under the pavement, the beach” rings in the air?

Principled positions as praxis

Cowardice as architectural theory is a framework for what Said describes as the reprehensible “habits of mind in the intellectual that induce avoidance,” that result in the “turning away from a difficult and principled position which you know to be the right one, but which you decide not to take.”11 That avoidance or turning away creates an ideological wall that separates urgent challenges from the institutional silence that envelops architectural education and practice. If critical theory offers a comprehensive outline to question the status quo, cowardice as architectural theory deliberately avoids engaging any pressing issues.12 This “turning away” can be summarized by apolitical discussions about ecology, so-called autonomy of architecture, non-referentiality, capitalist techno-determinism, or representational aesthetics that ignore architecture’s imbrication with white supremacist, heteropatriarchal, colonial regimes. Just as much work has been done to understand the common ground between different architectural theories, cowardice as a framework must be considered if we are to think seriously about avoidance as a political position, which equates the extermination of a people with their efforts at resistance.

For at least sixty years, critical race theory, feminist theory, trans theory, critical disability studies, critical Indigenous studies, queer theory, post-colonial theory, critical media studies, critical globalization studies, critical security studies, critical carceral studies, and critical theory of technology have emerged as fields of inquiry that inform how we think about the built, destroyed, and imagined environment.13 While these subjects all intersect with architecture, urbanism, and related fields at many points, the theory of cowardice focuses not so much on these intersections but on what happens when architects, urbanists, planners, and spatial designers willingly or unconsciously reject, disengage, obfuscate, erase, or overlook broadcasted genocides, the open persecution and silencing of intellectuals, and the repression of anti-apartheid actions.

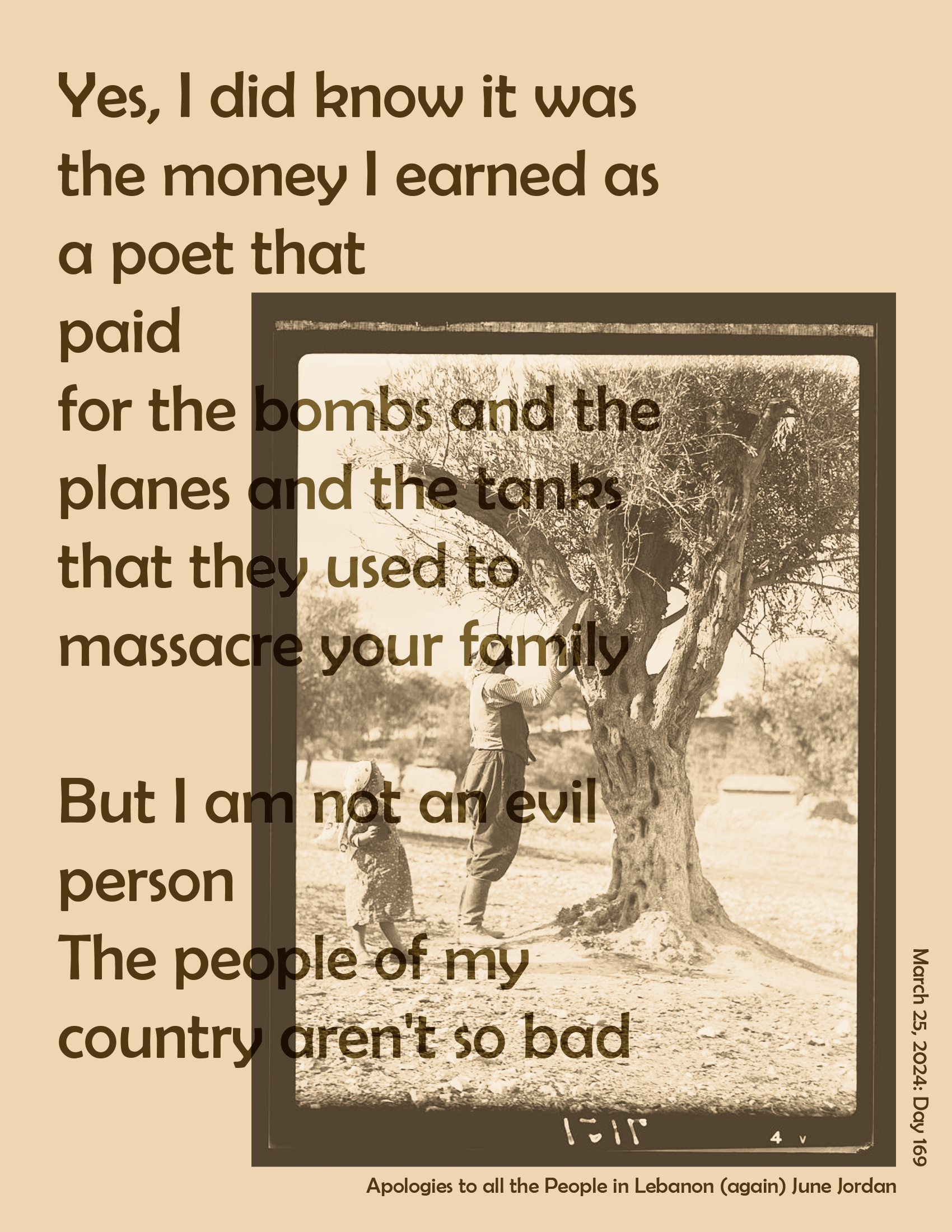

Against a theory of cowardice, moral bankruptcy, and criminal indifference, architects who confront their participation in the construction (material and ideological) of settler-colonial and ethnonationalist projects must adopt June Jordan’s posture in her 1982 letter “On Israel and Lebanon: A Response to Adrienne Rich from One Black Woman.” She writes, “I claim responsibility for the Israeli crimes against humanity because I am an American and American monies made these atrocities possible. I claim responsibility for Sabra and Shatilah [sic] because, clearly, I have not done enough to halt heinous episodes of holocaust and genocide around the globe. I accept this responsibility and I work for the day when I may help to save any one other life, in fact.”14 In “Moving Towards Life,” Marina Magloire explains how Jordan recognizes that being part of a violent system carries the obligation to critique its violence. A principled theory of architecture would identify how architecture has historically been a core part of systemic violence.15

Repression of critical theory

Cowardice is also reflected in the forms in which censorship, repressive legislation, and political persecution, among other strategies, seek to formally or stealthily impede academic freedom or freedom of inquiry.16 As we write this text, hundreds of laws have sought to ban critical race theory in the US alone, efforts that continue the historical persecution of Indigenous and Black activists over generations of state-sanctioned violence. Other forms of censorship are manifested in the numerous institutional efforts to silence voices for Palestinian liberation, including the attempts to censor a text on the legal implications of the Nakba by the Palestinian law scholar Rabea Eghbariah from the Harvard Law Review (successfully) and the Columbia Law Review (unsuccessfully).17 In the circles of architectural history and theory, the president of the AIA Middle East was ousted from his position for inviting the Israeli historian Ilan Pappé, who saw the presentation of his book The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine abruptly canceled at the request of the AIA’s Washington, DC, headquarters.18

Other examples of censorship include several attempts to silence and undermine anti-colonial efforts by the Algerian historian Samia Henni. Two took place at Cornell University. The first one was when, during the lecture series “Into the Desert: Questions of Coloniality and Toxicity,” the Chair of Architecture interrupted Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s presentation, “Palestine Is There, Where It Has Always Been,” with a message that that she’s “looking forward to organizing a future lecture that presents other viewpoints than those that are offered here today and in subsequent talks.”19 The second event took place as Henni’s office at Cornell was burglarized and vandalized, with the university never finding the culprit, reminding us of the time when Edward Said’s office at Columbia University was firebombed.20 More recently, Henni has received smear attacks from conservative news outlets in Switzerland authored by the German architectural historian Stephan Trüby, who has clearly sought to undermine her anti-colonial scholarship and silence her activism.21 These incidents occurred while anonymous death threats were left at her office at ETH Zurich, where she was teaching.22 These recent examples, the censoring of scholarship, the lecture interruption, the burglarizing and vandalization, the attacks from the newspaper, and the death threats, show how institutional cowardice is a threat not only to academic freedom and the production of knowledge but also to life itself. By cowering from studying architecture’s alliance with the cartographies of repression, supremacy, and colonial violence, architectural theory turns away from the violence inflicted on bodies and lands under occupation as well as the lives of people willing to study it.

If architecture claims (rightfully) that it has political agency and a social mission, then cowardice as architectural theory must be studied as a model of belligerent, malicious, supremacist, and naive practices, epistemologies, and criminal neglect. To study both, the violence directly generated by architecture and allied disciplines, and the censorship, repression, and persecution of those studying it, constitute an architectural analysis of the current moment. Aimé Césaire defines colonization as being the “bridgehead in a campaign to civilize barbarism, from which there may emerge at any moment the negation of civilization, pure and simple.”23 In its barbaric negation of civilization, cowardice as architectural theory is design, curricula, and administrative and planning decisions that support and maintain colonial campaigns and the regimes of repression that defend them.

Cowardice and AI

With the need to provide a conceptual and critical framework to the onlookers and practitioners, scholars, and administrators who produce theories and practices that benefit from regimes of terror, racialization, and subjugation, this theory operates retroactively, to understand how cowardice as architectural theory has been and continues to be practiced today. Once a framework is developed to identify cowardice as a form of theory, we can then reread the many anthologies of architectural theory of the last century and finally understand design, curricula, and administrative decisions. As a theory, cowardice is the heir apparent to the post-critical period. Rather than rejecting the critical outright, it avoids it. It turns away. This paradigm also leads us to cut out the political proclivities of the profession’s heroes. It will not admit Philip Johnson’s Nazism nor will it acknowledge Isamu Noguchi’s anti-lynching work or Jacques Rancière’s work on cinema about Palestine.

We can see how cowardice as architectural theory today is framed in academic discussions surrounding generative aesthetics and AI (artificial intelligence) while overlooking the degenerative aesthetics of automated killings and the racist profiling of algorithmic predictive policing and their relationship with carcerality and police violence.24 With publications emphasizing the potential positive outcomes of AI— “generating masterplan layouts, using given parameters such as daylight requirements, space standards and local planning regulations, right down to generating interiors and construction details”—architectural theory has looked the other way when it comes to questions of violence and militarization, ecology, and capitalism.25

Mainstream architectural discussions about AI seem fixated on discussing authorship, intellectual property, workplace efficiency, and speed of production. Meanwhile, they continue to ignore how, with a $200 billion projected investment by 2025—focused mostly on data centers like the ones providing support for Israel during its war on Gaza—advancements in artificial intelligence are joined by developments in robotics, autonomous weapons and vehicles, surveillance, and the collusion of tech giants and military contractors, including the Pentagon’s $9 billion cloud contract with Google, Amazon, Oracle, and Microsoft.26

A principled critique of architecture must apply to the prearranged marriage of technology, policing, carcerality, and war. As architectural forums and symposia discuss AI as a rendering engine or as a generator of plans, the Israeli army has launched Lavender, an AI targeting system with a violently permissive policy for casualties, to indiscriminately target thousands of Gazans as suspects and victims for assassination.27 By avoiding a critical and principled position, architectural theory has failed to address a broadcast genocide powered, in part, by AI.

To strip AI away from its weapons applications or energy consumption is inherently cowardly as design thinkers—or any person with social awareness and sensibility—should be capable of grasping both the benevolent and the nefarious applications of a tool. Through the lens of cowardice, architectural theory consistently misses the importance of thinking about the relationship between AI, Lavender, predictive policing, and the proliferation of Cop Cities across the US28 A principled position would shift architects to debate destruction, colonial violence, and the further instrumentalization of architecture in the necro-capitalist transformation of society toward militarized surveillance and automated policing, where tech companies and armed forces dictate zoning regulations as well as who gets to live or die.29 Cowardice declines to engage with the principled position of challenging the violent role of these urban-scale technologies, infrastructures, and programming (all of which are part of the dystopian package of the Smart City), rendering architects useless in the face of algorithmic processes that are already more efficient and have no labor rights.30

Critical theory and practice today

Cowardice as architectural theory is not new—the occupation of Palestine has been going on for over 76 years while the colonial project on Abya Yala is over 530 years old. Architecture as an institutionalized whole and an apparatus with several carefully codified arms (academia, private practice, nonprofit, governmental) has been unwilling to address its role in colonialism. In this cowardice, architecture continues to look away from the imperialist violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo or in Haiti in the same way as it ignored the civil rights movement in the 1960s. Because of their intricate connection to settler-colonial projects of modernity, development, progress, and universalism, most architecture schools and professional institutions in the Americas were founded under some form of racist or colonial regime.31 We can understand these architectural institutions and what they have historically produced as what Winona LaDuke and Deborah Cowen call—invoking the cannibal monster of Anishinaabe legend—“wiindigo infrastructure.”32 As the architectures of settler colonialism, wiindigo infrastructure “has worked to carve up Turtle Island, or North America, into preserves of settler jurisdiction, while entrenching and hardening the very means of settler economy and sociality into tangible material structures,” including “pipelines and dams and roads and prisons and toxic water infrastructures.”33

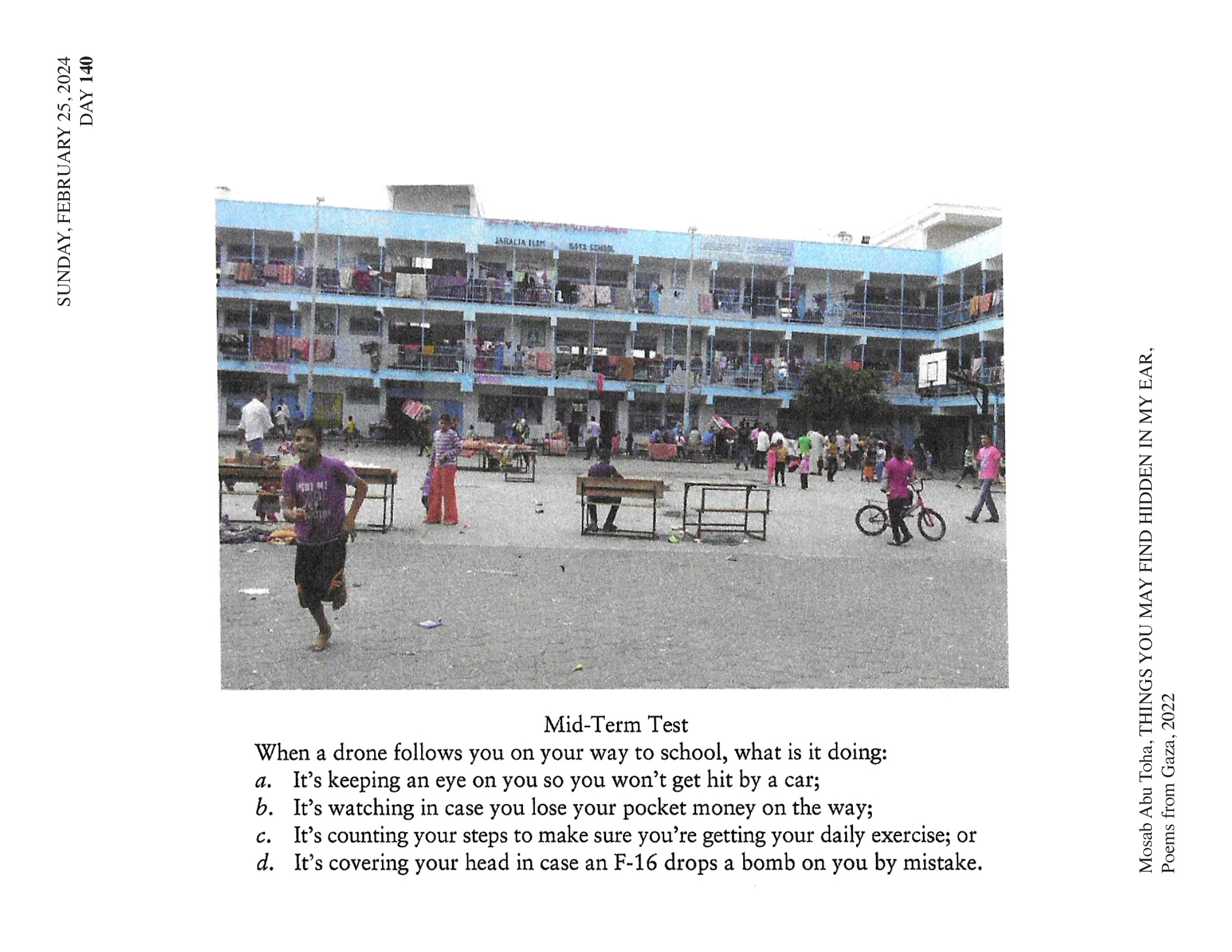

If cowardice as a form of architectural theory facilitates wiindigo infrastructures and their embodied violence, designers with the goal of helping to produce the right conditions for life, and the positive transformation of society, must recognize that while omnipresent, cowardice is not the only option, and there is work being produced that counters the politics of looking away. Principled theory as a model of thinking and action has been at the core of anti-racist, anti-colonial, and anti-apartheid protests, whether now, in the 1960s, or in the 1980s—when the language for divestment we see at play today was set.34 We can see this principled position in the many “Liberated Zones” or “Gaza Solidarity Encampments,” as they expose complicity and demand accountability as academic institutions invest in an apartheid state that has destroyed all 12 higher education institutions in Gaza, killed over 95 professors, and detonated more than 315 mines to obliterate Israa University, the last remaining university in the Strip.35

In response to this destruction, an exhibition and workshop series at a83 gallery in New York titled what is a school? displayed posters made in solidarity with Palestinian resistance as part of a call by the secret poster club of Columbia GSAPP students. The posters include reading lists, statements, and poetry on Palestinian solidarity and anti-apartheid resistance by Malcolm X, June Jordan, Mahmoud Darwish, and Edward Said, providing a clear form of principled theory in solidarity practices.36

The students’ decision to hold the exhibition outside the architecture school—where many posters were originally either torn down by university administration or anonymously plastered with Zionist propaganda—underscores a rift between the university’s complicity with colonial violence and the students’ principled stance against oppression. As administration and faculty remain silent and watch from a distance, students continue to face harassment and intimidation from university presidents and boards of directors, many with military and security investments, in collusion with state politicians and billionaire donors who deploy heavily armed police to attack and arrest them.37

Now, as students outline with their encampments, posters, exhibitions, and teach-ins, various forms of solidarity, resistance, alternative forms of pedagogy, and knowledge exchange, as they clearly map the connections between the military-industrial complex, the industrial carceral complex, policing, capitalism, apartheid, genocide, ecocide, architecture, the city, and the university, it becomes increasingly unavoidable to engage with these topics on all possible architectural fronts. As looming external and internal threats to academic freedom seek to reinforce the white, Western-centric status quo that has violently imposed certain ways of seeing and knowing on the world, we need more principled positions and critical theories in architecture that refuse to remain silent and complacent in the presence of injustice.

Architecture’s historic incapacity to take the principled position puts architects at risk of complete social irrelevance or, worse, in unshakable alignment with the destruction of life. As Whitney Young Jr. declared in his speech to the AIA in 1968, “It would be the most naïve escapist who today would be unaware that the winds of change, as far as human aspirations are concerned, are fast reaching tornado proportions... for a society that has permitted itself the luxury of an excess of callousness and indifference, we can now afford to permit ourselves the luxury of an excess of caring and of concern.”38 Against this callous indifference, and following the principled position of student initiatives, to refuse naive escapism today we must produce necessary and urgent knowledge and actions.

If cowardice is not the goal of architectural theory, pedagogy, and practice, then scholars and practitioners need to continue challenging dominant narratives and exploring the ways in which architecture continues to be used as a tool of oppression and marginalization. It is only by confronting inconvenient truths that may incriminate architects, university administrators, boards of directors, and donors that we can begin to move toward a more just and equitable environment for all. In search of architectures that lead us to human emancipation, in the future we may see not only genocidal political leaders tried at the International Court of Justice but contributing and complicit architects being prosecuted with crimes against humanity as well.

Meanwhile, if, as Said once said, “you do not want to appear too political; you are afraid of seeming controversial; you need the approval of a boss or an authority figure; you want to keep a reputation for being balanced, objective, moderate; your hope is to be asked back, to consult, to be on a board or prestigious committee, and so to remain within the responsible mainstream; someday you hope to get an honorary degree, a big prize, perhaps even an ambassadorship,” we are doomed to continue supporting the regimes of brutality and subjugation, and with it betray our role as educators and designers in search of the social good.39

During times of extreme colonial violence, architectural theory that systematically disengages with the critical questions of the times functions as an accessory to these unspeakable crimes. As the necropolitical architectures of human and ecological destruction—with their settlements, embassies, campuses, and checkpoints—are deployed, no position is neutral, because, as Fanon wrote, “Every onlooker is either a coward or a traitor.”40

-

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Constance Farrington (New York: Grove Press, 1963), 199. ↩

-

Noor Hindi, “Fuck Your Lecture on Craft. My People Are Dying,” Poetry Foundation, 2020, link. ↩

-

Move to innocence, or settler move to innocence, is a concept that Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang borrowed from Janet Mawhinney’s master’s thesis, in which she analyzes “strategies to remove involvement in and culpability for systems of domination.” See Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education and Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40. ↩

-

Tuck and Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” ↩

-

Max Horkheimer, “Traditional and Critical Theory,” in Critical Theory: Selected Essays, trans. Matthew J. O’Connell and others (New York: Continuum, 2002), 218. ↩

-

See Sharon Rotbard, White City, Black City: Architecture and War in Tel Aviv and Jaffa (London: Pluto Press, 2015); Horkheimer, “Traditional and Critical Theory,” 188, 198–199. ↩

-

Some of the most extreme examples of these theory impasses are Kate Nesbitt, ed., Theorizing a New Agenda for Architecture: An Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965–1995 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996), with its overrepresentation of white voices, zero Black or Indigenous theorists, and a chapter on gender with Bernard Tschumi, Peter Eisenman, and Diana I. Agrest as the only authors; K. Michael Hays, Architecture Theory Since 1968 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000); Pier Paolo Tamburelli, On Bramante (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022); Pier Vittorio Aureli, The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011); Patrik Schumacher, The Authopoiesis of Architecture, Vol. 1: A New Framework (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, 2010); Markus Breitschmid, Non-Referential Architecture: Ideated by Valerio Olgiati (Zurich: Park Books, 2019); and Mario Carpo, Beyond Digital: Design and Automation at the End of Modernity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2023). ↩

-

Edward W. Said, Representations of the Intellectual (New York: Vintage, 1996), xvii. ↩

-

Said, Representations of the Intellectual, xvii. ↩

-

Here we’re referencing the old cliché of architectural education, Louis Kahn’s “You say to a brick, ‘What do you want, brick?’ And brick says to you, ‘I like an arch.’ And you say to brick, ‘Look, I want one, too, but arches are expensive and I can use a concrete lintel.’ And then you say: ‘What do you think of that, brick?’ Brick says: ‘I like an arch.’ ” Oliver Wainwright, “Louis Kahn: The Brick Whisperer,” Guardian, February 26, 2013, link. ↩

-

“For an intellectual these habits of mind are corrupting par excellence. If anything can denature, neutralize, and finally kill a passionate intellectual life it is the internalization of such habits. Personally, I have encountered them in one of the toughest of all contemporary issues, Palestine, where fear of speaking out about one of the greatest injustices in modern history has hobbled, blinkered, muzzled many who know the truth and are in a position to serve it. For despite the abuse and vilification that any outspoken supporter of Palestinian rights and self-determination earns for him or herself, the truth deserves to be spoken, represented by an unafraid and compassionate intellectual.” Said, Representations of the Intellectual, 100. ↩

-

See Simon Malpas and Paul Wake, eds., The Routledge Companion to Critical Theory (London: Routledge, 2006). ↩

-

Cruz Garcia and Nathalie Frankowski, “Loudreading in Post-colonial Landscapes (to the Beat of Reggaeton),” Avery Review, no. 48 (June 2020), link; we credit the Algerian historian Samia Henni with providing this description as a field of inquiry. ↩

-

Marina Magloire, “Moving Towards Life,” Los Angeles Review of Books, August 7, 2024, link. ↩

-

Magloire, “Moving Towards Life.” ↩

-

In the US, there’s a growing number of states that have banned or tried to prohibit topics associated with critical race theory. For recent coverage, see Stephen Sawchuk, “Anti-Critical-Race-Theory Laws Are Slowing Down. Here Are 3 Things to Know,” Education Week, March 26, 2024, link; Alicia Hawkins, “Lawmakers Introduced 563 Measures Against Critical Race Theory in 2021 and 2022,” UCLA Newsroom, April 6, 2023, link; and Taifha Alexander, LaToya Baldwin Clark, Kyle Reinhard, and Noah Zatz, “CRT Forward: Tracking the Attack on Critical Race Theory,” UCLA School of Law Critical Race Studies, 2023, link. ↩

-

Rabea Eghbariah, “The Harvard Law Review Refused to Run This Piece About Genocide in Gaza,” The Nation, November 21, 2023, link. To read the most updated and extended text, see Rabea Eghbariah, “Toward Nakba as a Legal Concept,” Columbia Law Review 124, no. 4 (May 2020), link. ↩

-

Zach Mortice, “An Ouster at the Institute,” New York Review of Architecture, September 1, 2022, link. ↩

-

“Palestine Is There: A Problem, Evidently, for the Cornell Chair of Architecture,” The Funambulist, October 6, 2020, link. ↩

-

Conor McCarthy, “Edward Said Showed Intellectuals How to Bring Politics to Their Work,” Jacobin, December 11, 2021, link. ↩

-

Trüby has also published newspaper articles aiming at Léopold Lambert, Anne Holtrop, the feminist collective Parity Group, and Ariella Aïsha Azoulay. ↩

-

Daniel J. Roche, “ETH Zurich Students, Faculty, and Alumni Sign Letter of Support for Dr. Samia Henni After She Received a Death Threat,” Architect’s Newspaper, June 5, 2024, link. ↩

-

Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism, trans. Joan Pinkham (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2000), 40. ↩

-

Matthew Guariglia, “Technology Can’t Predict Crime, It Can Only Weaponize Proximity to Policing,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, September 3, 2020, link; Will Douglas Heaven, “Predictive Policing Algorithms Are Racist. They Need to Be Dismantled,” MIT Technology Review, July 17, 2020, link; and Will Douglas Heaven, “Predictive Policing Is Still Racist—Whatever Data It Uses,” MIT Technology Review, February 5, 2021, link. The term “military-industrial complex” was coined by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1961. It refers to the close relationship between the military and the defense industry, warning that this relationship could be harmful to democracy. The pursuit of profit can influence military policy and spending, leading to concerns about overspending, inefficiency, and corruption. See “President Dwight D. Eisenhower's Farewell Address (1961),” National Archives, link. ↩

-

Mario Carpo, “Excessive Resolution: Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Architectural Design,” Architectural Record, June 1, 2018, link; Oliver Wainwright, “ ‘It’s Already Way Beyond What Humans Can Do’: Will AI Wipe Out Architects?” Guardian, August 7, 2023, link. ↩

-

Jennifer Sor, “AI Could Power the US Economy as Investment in the Sector Is Poised to Hit $200 Billion by 2025, a Goldman Sachs Says,” Business Insider, August 2, 2023, link; Maggie Harrison Dupré, “Palantir’s Military AI Tech Conference Sounds Absolutely Terrifying,” Futurism, May 21, 2024, link; Jeff Decker and Eric Li, “How Software Companies Can Enter the US Defense Market,” Harvard Business Review, July 14, 2023, link; “Pentagon Splits $9 Billion Cloud Contract Among Google, Amazon, Oracle and Microsoft,” Reuters, December 8, 2022, link. ↩

-

Yuval Abraham, “‘Lavender’: The AI Machine Directing Israel’s Bombing Spree in Gaza,” +972 Magazine, April 3, 2024, link. ↩

-

This act of ignoring the necropolitical architectures of surveillance and death is not unique to Gaza, as Metro 21: Smart Cities Institute at Carnegie Mellon University sells predictive policing software to the police department in Pittsburgh. See Ashley Murray and Kate Giammarise, “Pittsburgh Suspends Predictive Policing Program That Used Algorithms to Predict Crime Hot Spots,” Pittsburgh Post Gazette, June 23, 2020, link; see also Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019); and Azadeh Shahshahani, “Cop Cities in a Militarized World,” Boston Review, September 15, 2023, link. ↩

-

Mbembe, Necropolitics. ↩

-

Stephen Cousins, “Architects Tap in to Gen AI for Design and Business Efficiencies,” RIBA Journal, June 7, 2024, link; Bradford J. Kelley, “Belaboring the Algorithm: Artificial Intelligence and Labor Unions,” Yale Journal on Regulation, June 15, 2024, link. ↩

-

WAI Architecture Think Tank, “Un-Making Architecture: An Anti-Racist Architecture Manifesto,” Architect’s Newpaper, June 15, 2020. ↩

-

Winona LaDuke and Deborah Cowen, “Beyond Wiindigo Infrastructure,” South Atlantic Quarterly 119, no. 2 (April 2020): 243–268. ↩

-

LaDuke and Cowen, “Beyond Wiindigo Infrastructure.” ↩

-

Omar Barghouti, Tanaquil Jones, and Barbara Ransby, “Let Us Remember the Last Time Students Occupied Columbia University,” Guardian, May 3, 2024, link. ↩

-

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner, “UN Experts Deeply Concerned over ‘Scholasticide’ in Gaza,” April 18, 2024, link; “How Israel Has Destroyed Gaza’s Schools and Universities,” Al Jazeera, January 24, 2024, link. In addition to the universities, Israel’s attack on Gaza has destroyed over 80 percent of schools, in what many have called scholasticide. See Chandni Desai, “Israel Has Destroyed or Damaged 80 Percent of Schools in Gaza. This Is Scholasticide,” Guardian, June 8, 2024, link. ↩

-

Daniel J. Roche, “At a83, Secret Poster Club Asks: what is a school?” Architect’s Newspaper, August 29, 2024, link. ↩

-

Hannah Natanson and Emmanuel Felton, “Business Titans Privately Urged NYC Mayor to Use Police on Columbia Protesters, Chats Show,” Washington Post, May 16, 2024, link. ↩

-

Whitney M. Young Jr., “Full Remarks of Whitney M. Young Jr.,” AIA Annual Convention, Portland, Oregon, June 1968. ↩

-

Said, Representations of the Intellectual, 100. ↩

-

Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, 199. ↩

Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz Garcia are architects, educators, authors, curators, and co-founders of WAI Architecture Think Tank and the public platform of pedagogy and trade school LOUDREADERS. They are authors of Universal Principles of Architecture: 100 Archetypes, Methods, Conditions, Relationships, and Imaginaries, A Manual of Anti-Racist Architecture Education, Narrative Architecture: A Kynical Manifesto, and Pure Hardcore Icons: A Manifesto on Pure Form in Architecture. They have edited volumes on Reparations, LandBack, and Post-Colonial Narrative Architectures.