Before the banking collapse of 2008, Dubai’s master plan included a range of waterworks—three palm islands, a world island, and a canal project. The latter depicted a dramatic extension of Dubai Creek circling around a large portion of the city before pouring out onto the Arabian Gulf. After the crash, the project stalled even though land had been cleared in anticipation of the expansion. In December 2012, Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum reactivated the project. Dubai Creek Canal, now under way, will form a water belt around Bur Dubai, Business Bay, the cluster of high-rises on Sheikh Zayed Road, Downtown Dubai—where Burj Khaleefa sits—and some parts of the residential neighborhood of Jumeirah. The width of the half-circle canal will range between 80 and 120 meters wide. It is estimated that around 800 million cubic meters of water will flow through the canal each year, generating a “cooling effect” akin to the climatic adaptations of the Cheonggyecheon stream in Seoul, South Korea. Upon completion, the canal will make a new Dubai island.

Dubai Creek is the maritime commercial artery of Dubai. Port Saeed, near its mouth, is a major hub in the Gulf trade route that links Basra, Bahrain, Dubai, and Muscat to the East Coast of Africa, Pakistan, and India. In the state-sanctioned modern histories of the city, the creek is always used as Dubai’s story of origin. The creek, as a waypoint in that trade network, became the site for Dubai’s early bids for regional prominence and cosmopolitan standing: Various proposals for convention centers, hotels, and the Dubai World Trade Center envisioned the city radiating from the creek, though these plans didn’t come to pass. Today, Deira, the urban district surrounding the creek and the port, is one of the city’s main commercial nodes, even though most contemporary images of the city are associated with southern Dubai with its many malls, housing enclaves, and stratospheric towers. The repurposing of the creek speaks to a new paradigm of development in the city, and of urbanization globally.

The canal project began late in 2012 and its full weight was only felt a few months ago when its construction diverted Sheikh Zayed Road—a fourteen-lane highway and Dubai’s main transport axis. Rerouting traffic in Dubai is nothing unique. Roads are continuously reinscribed as determined by exogenous political and economic forces (the exogenous being the raison d’être of Dubai). This particular diversion, however, was different; it points to a new development in the regimes that govern Dubai’s urban history and the new organizational and infrastructural systems they bring.

Urban works in Dubai are distinguished by a “development in the dark” approach. Projected images, in this scenario, are realized on vacant desert land. This “empty” or “nothingness” image of Dubai has become vital for the city’s marketing, in which Dubai’s grandness appears most powerful juxtaposed with emptiness, giving rise to the decontextualized narrative of the city. The story goes as follows: We were pearl divers. In 1966, oil was found at the Fateh field, oil revenues fueled Dubai’s commercial and tertiary sector development, and consequently the city entered the global neoliberal marketplace. Under this narrative, Dubai’s geography is depoliticized and the city only appears as remarkable in relation to its pre-modern, pre-oil “Old World” society. The creek expansion, however, is a radical reshaping of an already built-up area, as well as a relocation of Dubai’s main transactional axes. The project’s promise, as expounded by the urban and transport authorities of Dubai, borrows from a vocabulary of Emirati economics and cites a lexicon of urban precedents: From the significance of the Sheikh Zayed Road in paving (literally) the 1971 Emirates federation union, to the importance of the creek in maintaining Dubai’s capital flow, the canal project is clearly the creek’s next step in Dubai’s commercial evolution, layering a yacht-filled inlet lined by luxury residences over a functioning port.

What is particularly new about the canal project is how it transgresses discourse around Dubai as a fixed geographical entity. Rather, the project purports that unique and often ephemeral territorial configurations, such as special economic zones, enclaves, and islands, might be a more useful vocabulary for studying Dubai’s built environment and some contemporary urbanism in general.

The creek extension slices off the area that experienced some of the earliest pangs of Dubai’s property-led development in the early 2000s and today is its epicenter of hyperbolized global architecture—what is being marketed as “The Centre of Now.” In short, it is the heart of the free market. The marketing slogan is also a semiotic reduction of the city with designated territorial boundaries that work to reveal, hide, and erase some of the city’s multiple urban layers. In contrast to earlier images of Dubai’s spatial infiniteness, the island-zone proposal suggests a spatial constriction of Dubai as a place, wherein certain geographical and urban features are added or omitted. It groups the “privileged” areas that are commercially used to represent the city and stacks them all on one island. Already, Dubai subordinates the nation that it belongs to—in most accounts, Dubai and the UAE are portrayed as separate rather than nested places. In effect, Dubai Creek’s island-zone will extend this logic and subordinate the city underneath its own economic purview. Growth in the Emirates has been neatly—and sometimes not so neatly—stenciled around an elongated boundary, the coast of the Arabian Gulf. The Creek Canal, once it is complete, will be the leak at the center of the nation-state.

It also is an exemplification and physical literalization of Dubai’s detachment from its hemispheric and geopolitical position. Dubai and the UAE are in many ways unique within the Middle East. The UAE was one of the last states to gain independence in the region, and didn’t experience the Nasserist euphoria or the tricontinental spirit (not because it was nonexistent, but international and regional attention to the place was scarce). Dubai’s economy is mainly built on the service and, more recently, the property industry—not oil, which is the most profitable industry nationally (see: Abu Dhabi). In contrast to the region’s Arab heritage, Dubai has a significant number of people from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Iran, and the Philippines, and any street-level acquaintance of the city will tell you that Arabness in Dubai is mainly mobilized as motif and as a silhouette of power. As such, Dubai’s geographical history renders it more akin to Singapore, Hong Kong, Panama, or other maritime ports that are somewhat detached from their immediate hinterlands, and become instructive or exemplars of a broader global urban phenomenon. Together, they share an economic template that has in recent decades allowed for the speculative real estate, exploitative labor, and minimal taxes that mark them capitals of a neoliberal trade. They are the new forms of the export processing zone or Hamburg’s free port model—enclaves of a unique breed of urbanism.

In Keller Easterling’s Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space, the “zone” is described as “heir of the mystique of ancient free ports, pirate enclaves, and other entrepôts of maritime trade.”1 Contemporary free zones are developed as spaces for economic liberalism, market manipulation and regulation, as well as special areas for export and business. They are also designed to be attentive and responsive to global flows of trade. Other than designating land for the “Export Processing Zone,” countries today focus on a specific city-region and convert it to a special economic zone/belt/corridor linking it to the extraterritorial geographies of the global neoliberal market.

If the zone is in fact a precisely delineated space, there are cities where one feels that the logistical template and spatio-economic ideology of the free zone are applied to the entirety of the city. Sites like Dubai, Singapore, and Hong Kong are go-to examples; Easterling, for instance, neatly places the three examples in the first 800 words of her book. Although favorites of urbanists, the connections typically made between them feel safe, soft, and lacking in rigor. Of course, one of the main relationships that appear between these places is their British colonial past. As an example: The British Empire was curious about Dubai, not only for its oil but as a potential port in its vast maritime network. In 1967, leftist, anti-British riots in what was the English colony of Hong Kong had alarmed the colonialists. Revolts against the British indicated that the island might join the People’s Republic of China. The concerned government, seeking to ensure global market presence, found Dubai and many other Gulf port cities to be lucrative Asian positions for their colonial franchise. Further, working with the British promised a bounty of international banks and conglomerates, as well as political support (such as entry into the United Nations). The latter was especially important for the UAE, as previous attempts for sovereignty faced resistance from the regional giants, such as Iran and Saudi Arabia, who produced much larger quantities of oil.

The urban form of these cities are connected by more than colonial trade routes—their geographies, whether natural or man-made, also indicate some of their potentials. If Dubai aspires to the economic template of Hong Kong or Singapore, is the final frontier an island? Once the canal project is complete, all three cities will be sectioned off by a body of water from a larger landmass, and so could we imagine the new Dubai island as its own nation city-state, untethered to the federation? Will it become a newer haven for tax evasion, economic citizenship, and even more deregulation than already exists? Can the island become its own independent entity? Will Dubai, too, have identitarian distinctions between mainlanders and islanders? If the built fabrics of the city already mirror these logics, might too their urban futures?

Islands, as conceptual objects, have generally been depicted as places of remoteness, isolation, and seclusion, not to mention the colonial imaginary of the island as a place for acquisition, purity, and nativity. It has repeatedly been imagined to be a uniquely sovereign place, where the surrounding sea acts as a shield from outsiderness. The island, too, is an ideal metaphor for a unified and unitary identity, achieved through its geographical separateness.2 This suggests that the islanded contours of Hong Kong, Singapore, and now Dubai might become conduits for a future urbanism in which free zones become nations through the model of an island-city-state complex. The new island-canal zone in Dubai is the superimposition of not just a policy or economy but a naturalized geography. Here fungibility takes place not only on the economic-political level, rather it is exercised over the land: The exportable land project creates a new polity. The breaking—or really, atomization—of parcels from larger land bodies is a geographical consequence of the modern capitalist civilization—alienation, individuality, etc.—and the cyclical continuation of continents breaking up. The zone, as designed by Dubai, is a political geography appearing in multiple dimensions and varied temporal scales. The Creek Canal is a forerunner of these.

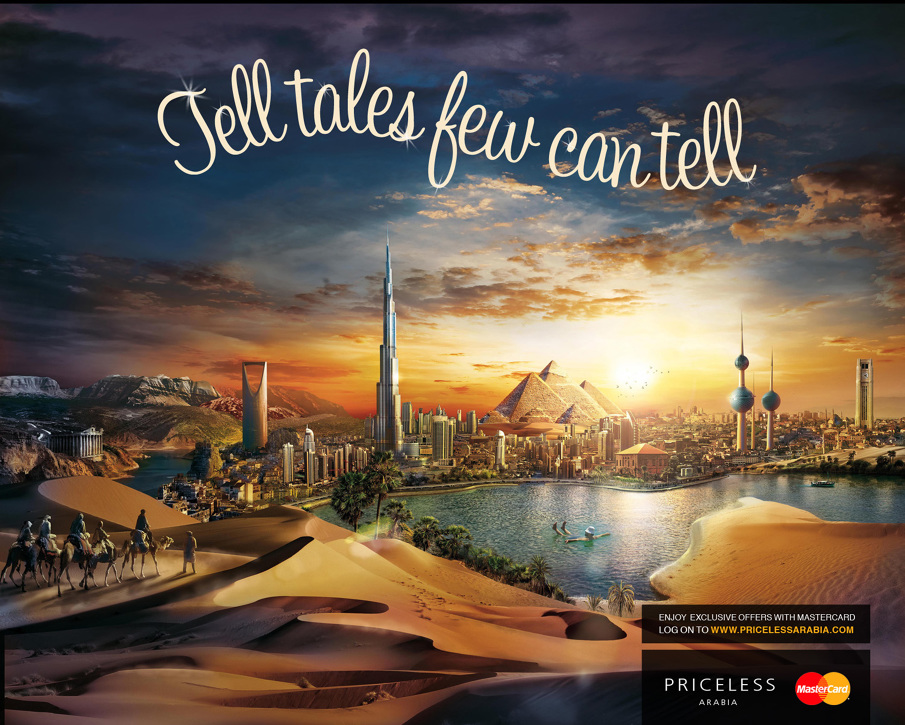

The Creek Canal Project, which will result in the parcelling-off of Dubai Island, is the city’s attempt at creating its doppelgänger, a slicker version of itself. In so doing, it aims to absorb the UAE’s and the Gulf-at-large’s global economic and political ambitions and then exemplify them. It becomes a satellite of sorts where cumbersome bureaucracy and territorial disputes are neutered, and where MasterCard’s “Possible Arabia” is actualized in a landscape of economic and political smoothness. Dubai Island is the promise of the “Gulf”—and all of its violences, inequities, and excesses—made manifest.

Ahmad Makia is a writer currently researching “The Pan-Arab Hangover” and living in Dubai. He is a co-editor of THE STATE.