The Cemetery

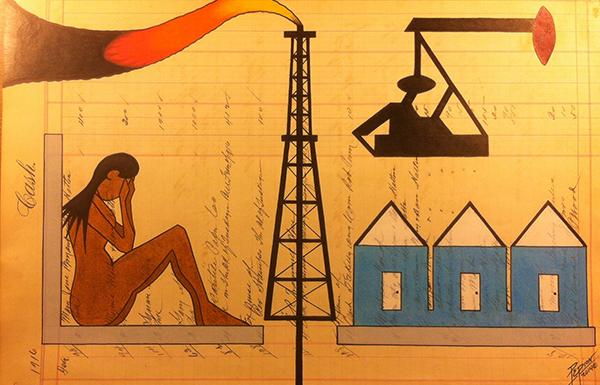

On the Great Plains, within the boundaries of the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation and the outline of New Town, North Dakota, is a small graveyard. With its carefully decorated headstones climbing a treeless bluff near the Missouri River, Snow Bird Cemetery forms a node in a complex global web of building, movement, and bodies. Despite its idyllic rural frame, the cemetery manifests the cycles of extraction that cyclically produce and empty these small towns. At Snow Bird, the dead no longer have a right to the customary silence of the Plains because a truck lot has moved in next door, connecting nearby oil production and distant refineries. The cemetery instead performs the grim task of covering bodies consumed by violence produced through the same networks that have deployed heavy machinery to the hill where it stands. New Town, built to replace communities sacrificed for the construction of the Garrison Dam in 1944, is also the product of longer patterns of violence against the Three Affiliated Tribes—the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara—inflicted by the US Army, the railroad, broken treaties, untenable agriculture, environmental degradation, and now, oil pipelines. It would be a mistake to characterize New Town, the Fort Berthold reservation, or the state of North Dakota as remote, somehow separate from the world aside from their ties to the global oil industry. Here, resource extraction, land ownership, and tribal sovereignty struggle against one another to define (inter)national sovereignty, community structures, and bodily rights as both physical practices and visions of the global future.

These abrupt collisions between small, rural, particularly indigenous communities and global networks of power and exchange are mediated by a particular architecture: the “man camp,” the temporary, sometimes ramshackle, portable housing deployed by oil companies to host their largely high-paid, itinerant workforce for months to years. The camps enable extractive industry—oil, fracking, natural gas, and mining—to exhaust “discoveries.” With structures ranging from worker-owned RVs and mobile homes to ready-made corporate barracks, the developments move from one site to the next—encampments contingent on the fluctuations of oil boom and bust—leaving behind bare fields to match depleted sites. As their name suggests, the camps are inhabited predominantly by men, who make up most of the temporary workforce in resource extraction. Examining the man camp as a typology with a particular mobility and a specific temporal frame allows us to ask how this architecture enacts violence against land and bodies both directly through its physical presence and proximity to majority indigenous communities and diffusely through its existence as a node in a larger network that mobilizes violence on the ground. Architecture’s role in this cycle of violence can be situated across three scales, each with a different temporality: the body (that absorbs temporariness), the camp (that enacts temporariness), and the global oil industry (that deploys temporariness). Identifying when violence is tolerated, and on what and whom, is fundamental to understanding rural America as contested architectural space. It is in this space, neither urban nor separate from the urbanized world, where the dreams of architectural modernity realize their human consequences.

The Body

In 2014, two organizations, the Women’s Earth Alliance and Native Youth Sexual Health Network, began to document the ways extractive industries affect the lives of indigenous women and youth in communities across North America. They produced a guide, Violence on the Land, Violence on Our Bodies: Building an Indigenous Response to Environmental Violence, to be circulated among geographically remote indigenous community networks. The guide consisted of statistics on crime spikes, a numerical narrative of the encounter between local space and unfamiliar labor; information on successful community organizing against these forms of violence; and healing exercises to reconnect very young victims of crime with traditional land-based practices.1 The guide can be read as an encounter between the orders of communal reciprocity and the logics of extractive industry, orchestrated by camp architecture. The authors explain that, if the Keystone XL Pipeline is approved for construction,

The threat to native bodies, disproportionately native women’s bodies, is rendered here as a geographical and architectural problem (the proximity of new temporary housing), codified by statistics and compounded by legal decisions that have limited indigenous jurisdiction over reservation land when perpetrators of violence are non-native, as well as over land beyond the reservation’s boundaries. The language of the problem, down to the “stripping” of tribal rights, clearly ties the threat of violent bodily confrontation to the temporary architecture that houses that threat in workable proximity to two sources of exploitation: subsurface resources and indigenous people. The “man camp” materializes connections between environmental and gender-based violence: “They think they can own us, buy us, sell us, trade us, rent us, poison us, rape us, destroy us, use us as entertainment and kill us,” Lisa Brunner (White Earth Ojibwe) explains.2 Manifested in the camp, settler colonial logics approach “wilderness” (that awaits development) and people (who belong intrinsically to the land) as equally consumable. As long as extractive infrastructures operate, indigenous bodies will be violated.

The Camp

The state of North Dakota operates at multiple and diffuse scales, pulled apart by its partnerships with the global oil industry and its aspirations for control over American Indian reservations. Conflict—the kind that often produces violence in different forms—abounds as the state negotiates with various parties who vest their interests in North Dakota’s land base or what lies beneath it. Historically, the fort and prison camp, followed by the enclosure of reservations, were the first architectural and spatial typologies to express settlers’ claims to indigenous peoples’ lands. These architectural legacies, connected by lines of incursive rail and steamboat infrastructure, are a fixative point for modernist architectural thinkers concerned with the American landscape. It is the coupling of the expansionist project with infrastructural technologies in the American West that prompts Reyner Banham’s technological determinism, for example, when he writes “over most of the US there was neither society nor landownership until mechanization came puffing in on railroads that were often the first and only geographical fixes the Plains afforded.” This single statement makes clear both his dismissal of indigenous sovereignty on the basis of Eurocentric notions of civilization, and the dominating role of transportation technologies in the West.3 Foregrounding colonization on the Plains as the birth of a conceived technological utopia is no accident; Banham goes on to say,

The language of “beyond” as a technological, possibly architectural frontier depends here on tying industrial mutilation of “virginal” “wilderness,” a dismissal of American slavery, and indigenous death up in a single breath. While Banham’s ironic tone appears to condemn the ideological and physical violence of “manifest destiny,” he does not acknowledge that it was that violence that made industry possible. This language embeds sexual vulnerability in the land, echoing violence at the scale of bodies up to that of the camp and its mobile, technologically enabled infrastructures.

Buckminster Fuller takes terra nullius to mean the terrain of industrial invention and technological progress itself. In a 1966 interview, he introduces the concept of the “outlaw area.” He declares that “the whole development of technology has been in the outlaw area, where you’re dealing with the toughness of nature. I find this fascinating and utterly true. All improvement has to be made in the outlaw area. You can’t reform man, and you can’t improve his situation where he is.”4 In this conception of frontier land, man (from a presumably urban interior) encounters nature, developing both the essential technologies for his own survival and the innovations for transforming human society from the outside. As an exploitative model, this form of innovation raises the question of ownership: to whom do these innovations belong? This right to explore, discover, and harness space beyond the carefully drawn margins of civilization, while it emerged from idealistic—and perhaps, myopic—countercultural thought, is an essential foundation for the oil industry’s contemporary language.5 Threats to human and environmental health are dismissed by casting rural space as a vast absorptive emptiness, devoid of meaningful society or deserving populations. Meanwhile, oil “discoveries” are described as belonging to the whole nation, as resources providing security as well as a lifestyle to which urban people are accustomed. This model of extraction relies on a clear division between those who deserve the security of the nation and the comforts of technology developed at and used in its periphery, and those whose influence is not sufficient to overcome corporate deniability, remaining invisible non-users in modernism’s globalizing architectural narratives.

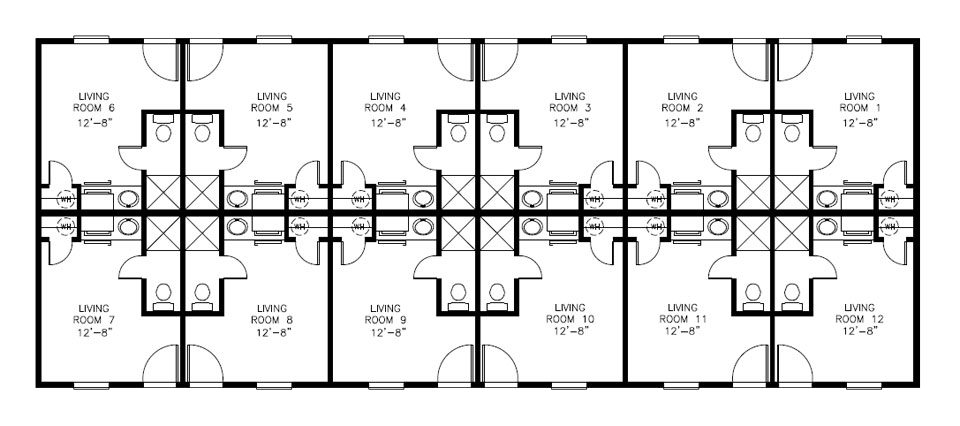

The “man camp” is stationed at “remote” sites of extraction within Fuller’s “outlaw area.” Typically bought from and assembled by a contractor providing complete camp infrastructures through online order, or formatted as a Bring Your Own Housing RV park, these camps are an essential feature of oil and gas development in the rural West and the visible material tie to globalized systems of capital and labor.6 Banham’s criteria for the ideal American product are presciently similar to “man camp” architecture:

This web-ordered architecture is only coherent from a more distant vantage: from aerial photos, TV news, or floor plans. The “man camp” is generally drawn as one schematic unit or one multi-bunk module, but photographed as a full-scale complex assembly of a hundred or more individual units. This sharply differentiates the camp from the reservation. Though often composed of similar prefabricated homes and trailers, reservation housing is configured for radically different relationships and terms of habitation. This forms an important juncture for architectural analysis, where the logics of infrastructure and development aid merge.

“Man camps” in the Dakotas are also contentious in local government, where cities and counties compete for tax jurisdiction and struggle with the non-local burden on local services including police, hospitals, and roads.7 Meanwhile, adjacent reservation communities have little say in the camps’ presence and are often left to stretch their resources to compensate for the sudden and sometimes violent impacts of temporary populations.8

The Extractive Network

Though reservation housing may share with man-camp shelters a typology and perhaps even a manufacturer, they differ sharply in their temporality. While the camps are intentionally short-lived components of an oil development budget, tribal housing is a term of most treaties that bind the United States and tribal nations. However, federal law complicates private property and ownership, and Indian Housing Authorities are chronically underfunded. Reservation communities are consistently excluded from the financial networks at play around them and at the same time encased in those very structures.

Governmental and industrial interests intersect at extractive infrastructures, mediated by the language of development and the architecture that organizes that language on the ground. Timothy Mitchell connects the motivations for temporary architectures to the material infrastructure that circulates them. Mitchell writes, “the oil, whose location, abundance, density and other properties shape the methods and apparatus of its control.” He goes on to say that, “this apparatus, composed of machinery, men and women, knowhow, finance and hydrocarbons, is what we refer to in shorthand as the ‘oil firm.’ It might help to think of the firm, in a technical sense, as a parasite: an entity that feeds off something larger, the flows of energy.”9 Evidence of this imbrication of government and corporate interests can be found in a 1996 fact sheet from the Bureau of Indian Affairs that outlines the subsurface resources of the Fort Berthold Reservation. Through a chaotic patchwork of small text, dense scientific language, and diagrams, and a brief history of reservationization, the sheet provides a window into how the reservation is seen as a further frontier: a space of potential exploration. With this sheet, the federal agency charged with holding Indian lands in trust provides extractive industry with a map to exploiting that trust and the data to calculate Fort Berthold’s value according to networked industrial logics.

The Cemetery, Again

Indigenous peoples, whose land forms the foundation of the United States, often equate physical violence against bodies—such as police aggression and human trafficking—to environmental violence through resource extraction for both practical and traditional reasons. As Faith Spotted Eagle reminds us, “the specter of man camps [resurrects] U.S. militarization of the Plains during the 1800’s, when US Army forts fostered the systematic sexual brutalization of Native women by soldiers.”10 Today, violence against native people in North America is enacted through particular forms of environmental racism—from missing persons cases to the Dakota Access Pipeline—evident in the architecture around which violent encounters are staged and imprinted upon land and people. Historical moves through the treaty-making process of defining and maintaining the frontier can be theorized around the terms “encounter,” “enclosure,” and “outlaw area.” These terms have remained relevant to the language of globalized extractive industry, whose impacts on the body (particularly women’s and children’s bodies), the community, and the land depend on maintaining a perpetually distant frontier for further exploration. The frontier, located in “rural” space, may actually be growing more distant for the majority of urban people alienated from life on the land. Ultimately, as Iako’tsi:rareh Amanda Lickers (Turtle Clan, Seneca) says, “If you’re destroying and poisoning the things that give us life, the things that shape our identity, the places that we are from and the things that sustain us, then how can you not be poisoning us? How can that not be direct violence against our bodies, whether that be respiratory illness or cancer or liver failure, or the inability to carry children?”11 Temporary architectures for worker habitation restage the centuries-old violent “encounter” of frontier conflict for the benefit of extraction. They are instrumental in reproducing (inter)national narratives that frame sovereignty as the right to tame, to ruin, and to perform violence on earthly bodies.

-

Women’s Earth Alliance (WEA) and Native Youth Sexual Health Network (NYSHN), Violence on the Land, Violence on Our Bodies: Building an Indigenous Response to Environmental Violence (2014), 4–8.

Native women and families will be directly impacted by three main camps, which are proposed to house 1,000 workers each and would be located in Harding (less than 30 miles from the Rosebud reservation, less than 50 miles from the Yankton reservation, and located in Zeibach County—where 71 percent of the population is Native). Native women, who are already 2.5 times more likely to be sexually assaulted, are especially vulnerable as the 1978 Supreme Court case Oilphant v. Suquamish stripped tribes of the right to prosecute non-Natives who perpetrate crimes on the reservation.[^2]

-

Mary Annette Pember, “Brave Heart Women Fight to Ban Man-Camps, Which Bring Rape and Abuse,” Indian Country Today Media Network, August 28, 2013. ↩

-

Reyner Banham, “The Great Gizmo,” in Design by Choice (London: Academy Editions, 1981), 108.

The [pastoral] dream’s proliferation beyond the Appalachians, beyond the Mississippi, beyond the Rockies, increasingly depended at every stage upon the products of industry and the local application of mechanisms. For the first time, a civilization with a flourishing industry encountered a landscape that was entirely virgin, or, at worst, inhabited by scattered tribes of noble (or preferably, dead) savages.[^5]

-

Calvin Tomkins, “In the Outlaw Area,” the New Yorker, January 8, 1966. ↩

-

A deeper exploration of the relationships between indigenous people’s movements and architectural modernism or the hippie fringe of architecture in the 1960s is necessary but beyond the scope of this paper. It is crucial, however, that we do not discount the role of humanistic movements in theorizing and popularizing temporary architectures. Their writing is worth revisiting, bound as it is with a revisionist idealism of the American frontier and a familiar instinct to mythologize indigenous peoples for their own purposes. Reading these works with contemporary incarnations of their theories and projects in mind, including “man camps,” is necessary for both understanding the genesis of temporary typologies and decolonizing our architectural history. ↩

-

William Caraher, “The Archaeology of Man Camps: Contingency, Periphery, and Late Capitalism,” in The Bakken Goes Boom: Oil and the Changing Geographies of Western North Dakota, eds. William Caraher and Kyle Conway (Grand Forks: The Digital Press at the University of North Dakota, 2016), 184.

A small self-contained unit of high performance in relation to its size and cost, whose function is to transform some undifferentiated set of circumstances to a condition nearer human desires. The minimum of skill is required in its installation and use, and it is independent of any physical or social infrastructure beyond that by which it may be ordered from [a] catalogue and delivered to its prospective user.[^9]

-

Renée Jean, “City Files for Extra 1-Mile,” Williston Herald, April 11, 2015, and Ernest Scheyder, “North Dakota ‘Man Camps’ Battle Pending Ban in Oil Capital,” Reuters, November 23, 2015. ↩

-

Damon Buckley, “Firsthand Account of Man Camp in North Dakota from Local Tribal Cop,” Lakota Country Times, May 22, 2014; and Sierra Crane-Murdoch, “On Indian Land, Criminals Can Get Away with Almost Anything,” the Atlantic, February 22, 2013. ↩

-

Timothy Mitchell, Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil (New York: Verso, 2013), 44–45. ↩

-

Pember, “Brave Heart Women Fight to Ban Man-Camps, Which Bring Rape and Abuse.” ↩

-

WEA and NYSHN, “Violence on the Land, Violence on Our Bodies,” 14. ↩

Elsa MH Mäki is an Anishinaabe designer, writer, and mapmaker. She studied architecture at Columbia University and now works as an architectural designer in Minnesota.