At first glance, the San Miguel Gate, one of three official border crossings on the Tohono O’odham Nation in southern Arizona, might appear unguarded. But turn down the dirt road that leads to it, and it is typically but a matter of minutes until you’ll see the white and green of a Customs and Border Protection truck behind you. To cross here one needs to make an appointment ahead of time; one also needs to be O’odham and to be traveling on foot. Vehicles are not allowed to move through. The passage of the so-called Patriot Act severely restricted movement on what had once been open territory, leading to the creation of gates—like the one at Woo’san (San Miguel) or Stoni Shudag (Pagago Farms) farther west—to monitor and regulate border crossing. As rudimentary as this steel and wire gate may seem, it is part of a larger apparatus of security infrastructure aimed at the command and control of movement in the US–Mexico borderlands.

In March 2014, United States Customs and Border Protection (CBP) awarded Elbit Systems of America a contract to design, construct, and deploy Integrated Fixed Towers (IFT) in a string of unspecified sites along the southwestern border of the United States. Elbit’s responsibilities extended beyond construction to include in situ testing of continuous monitoring, ensuring customer satisfaction with their product’s ability “to detect, track, identify, and classify movement on the border.”1 While the location and number of such sites remained obscure, the objective of the towers was made clear: they were to be integral nodes in an increasingly robust border surveillance apparatus. This was militarized infrastructure, configured to give CBP command over the mountainous terrain of the Sonoran Desert and designed to control the populations that lived in and moved through it.

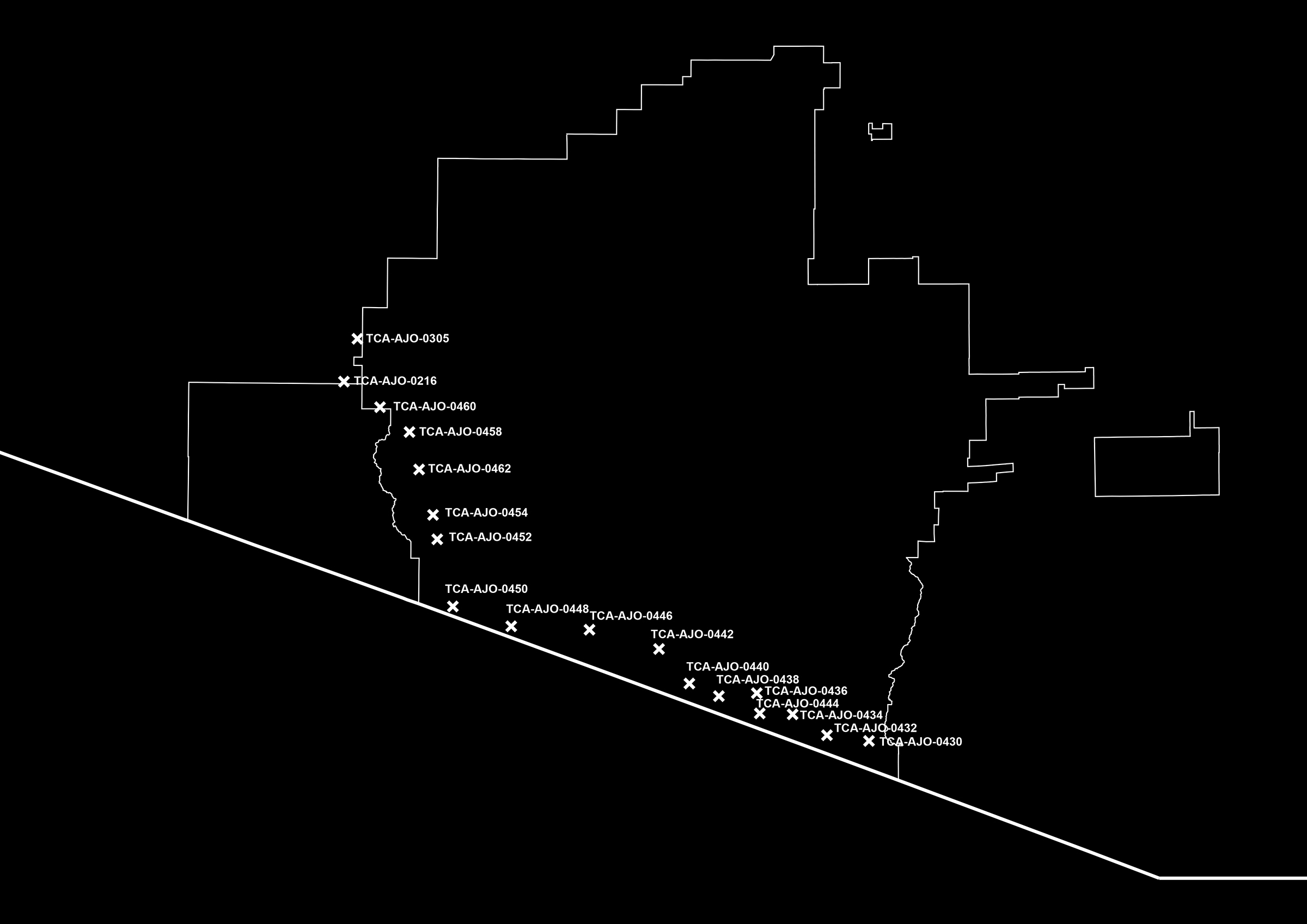

As the proposal now stands, sixteen Integrated Fixed Surveillance Towers will be erected in the indigenous Tohono O’odham Nation along its southern border with Mexico and its western border with the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument—a border that extends nearly thirty miles into the interior of the United States. Here, in a reservation on a border, imposed on a people whose lands, in fact, span across geopolitical boundaries, integrated fixed towers are a surveillance infrastructure that orders sovereignty, mobility, and land itself. Opposition to them is an act of refusal against the imposition of sovereign control of the state in indigenous lands and an assertion of the right of indigenous peoples to regulate movement within their lands on their own terms.

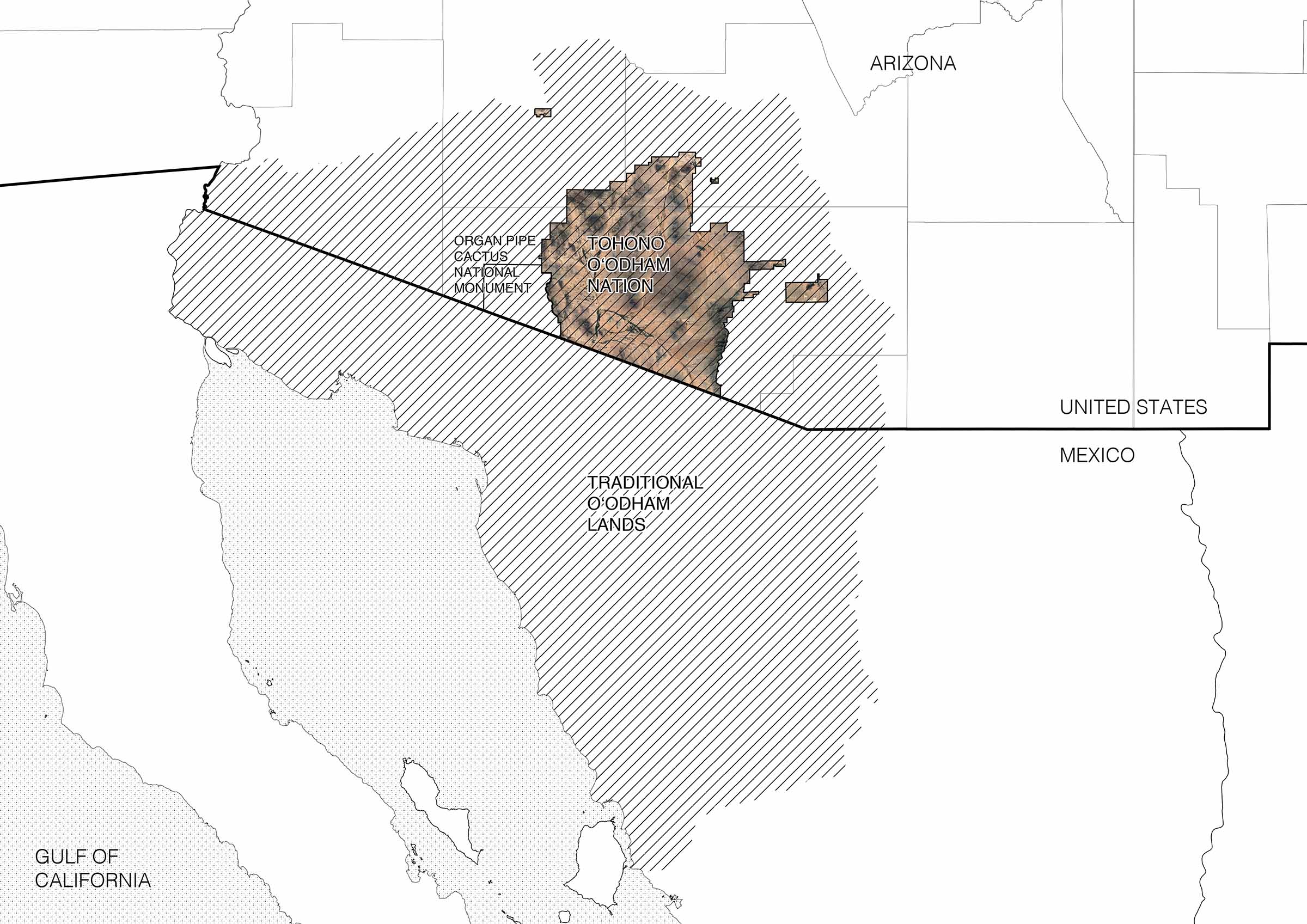

The Tohono O’odham traditional lands encompass thousands of square miles of the Sonoran Desert in a territory that straddles what is now the border between Arizona in the United States and Sonora, Mexico. Historically, the O’odham have moved fluidly through this terrain, traveling to seasonal villages, harvesting saguaro cactus, fishing in the Gulf of Mexico, and performing spiritual walks or runs. Yet today, the Nation occupies only a tenth of O’odham territory systematically reduced through five centuries of invasion, land purchases, and executive orders that the O’odham—then not recognized as a sovereign nation by the United States or Mexico—were not party to.2

The US–Mexico border is immaterial to the land forming the basis of O’odham life, but that border has become increasingly tangible since its imposition and increasingly obstructive over the last decades. Despite the constriction of their land base into a reservation, crossing the international boundary has remained a daily activity for the O’odham, necessary in order to visit family (many of the tribal members have family and residences on both sides), harvest traditional food, receive health care and education, partake in a cross-border economy, and to practice religious ceremonies. 3 The O’odham Nation’s constitution determines tribal membership on the basis of ancestry and not citizenship—meaning that O’odham born in Mexico are also members of a tribe, which is recognized by the United States government.4 With the Patriot Act, crossing the US–Mexico border along the Tohono O’odham nation was restricted to three “tribal gates”—San Miguel being one.5 Customs and Border Patrol manages these checkpoints where sufficient documentation—such as a passport or tribal ID, which many O’odham in Mexico do not have—is needed to cross. Crossing along ceremonial and informal paths was made illegal. A complex and increasingly tight condition of border militarization has resulted, as divergent understandings of property, connectivity, and permanence have created an impasse in which indigenous rights to the land are seen as incompatible with the perceived demands of national security. Here the towers deploy and weaponize not only the technologies that comprise them but also the terrain on which they stand. Cultural, spiritual, and territorial understandings of the landscape are interpolated in the infrastructural operation of the towers. Extending the radius of their impact beyond a physical footprint, they mobilize the topography of the land itself in an act of trespassing and transgression on the O’odham way of life, or himdag.

Constricted mobility through the tribal gates has been tightened further, and extended farther, by a more pervasive form of monitoring and control: the integrated fixed towers and the “persistent surveillance” that CBP touts them as enabling. Both tribal gates and integrated fixed towers impinge on movement and undermine territorial sovereignty by intervening in the landscape as a method of regulating social and political life.

Gates and Towers

Until recent years, CBP viewed the desert as a hot, inhospitable expanse—a natural barrier too harsh and depopulated for many migrants to travel. From the 1990s onward, the Department of Homeland Security’s Operation Gatekeeper used the perceived unknowability and danger of this terrain to funnel border crossing toward urban areas, or toward the eastern segment of the Rio Grande, where surveillance infrastructure was more robust.6 The desert became a topoclimatic device to channel the flows of migrants. Yet, as fears of drug trafficking increased during the Obama administration, and anti-immigrant rhetoric accelerated to fever pitch under Trump, the Sonoran Desert transformed from an “empty” terrain of deterrence to one of apprehension and fortification.

Tribal gates turned traditional pathways through contiguous territory into sites of encounter with state control, where CBP has to be notified ahead of time to come check documents—adding layers of state bureaucracy to routine movement, discouraging the act of border crossing, and criminalizing it for those who do not conform to new laws. Often O’odham in Mexico are unaware of these laws and can end up being apprehended, deported, and told they may no longer cross into their lands within what is now the United States (often O’odham in Mexico are unaware of these new laws). Here, border infrastructure criminalizes indigenous land use and annuls claims to sovereignty on the part of residents on both sides of the geopolitical boundary.

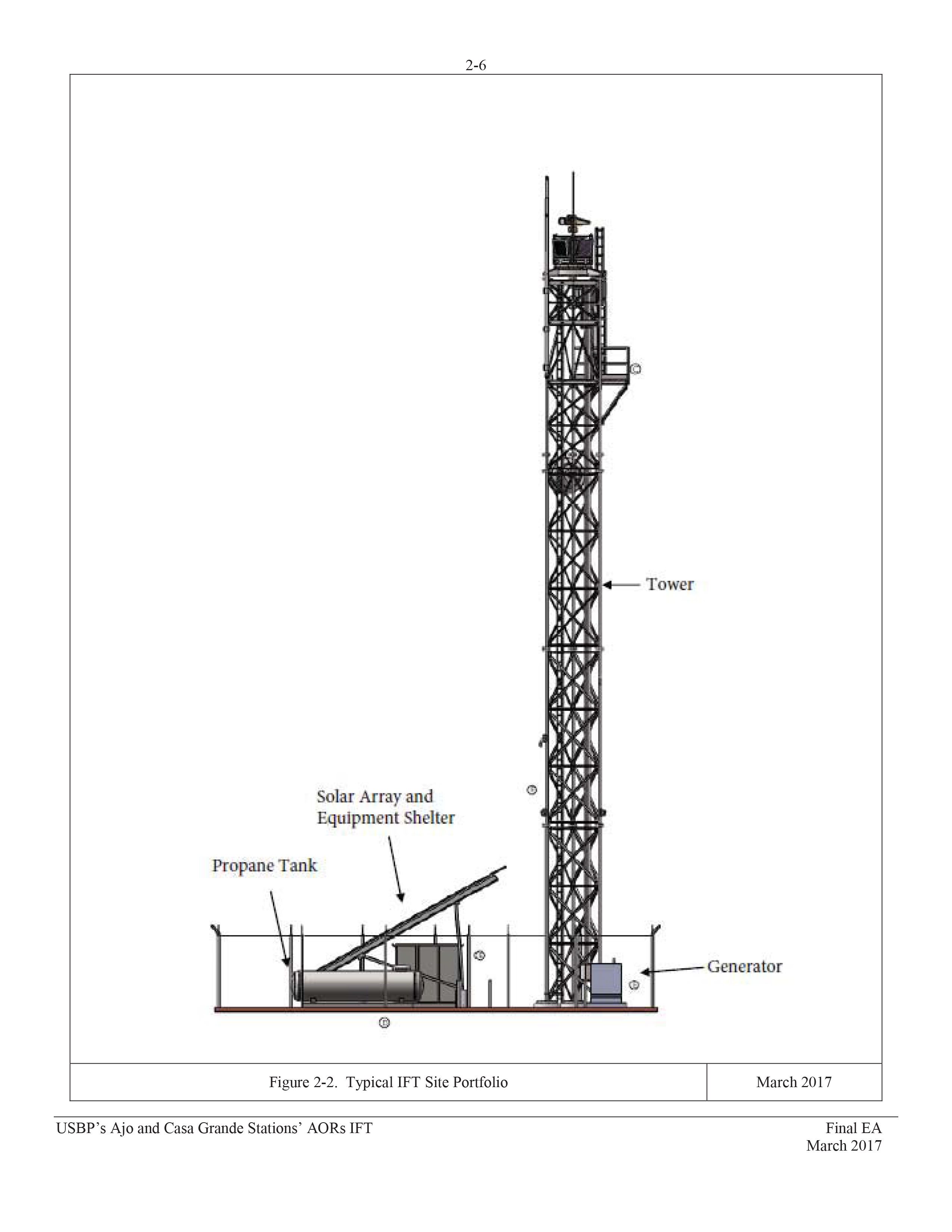

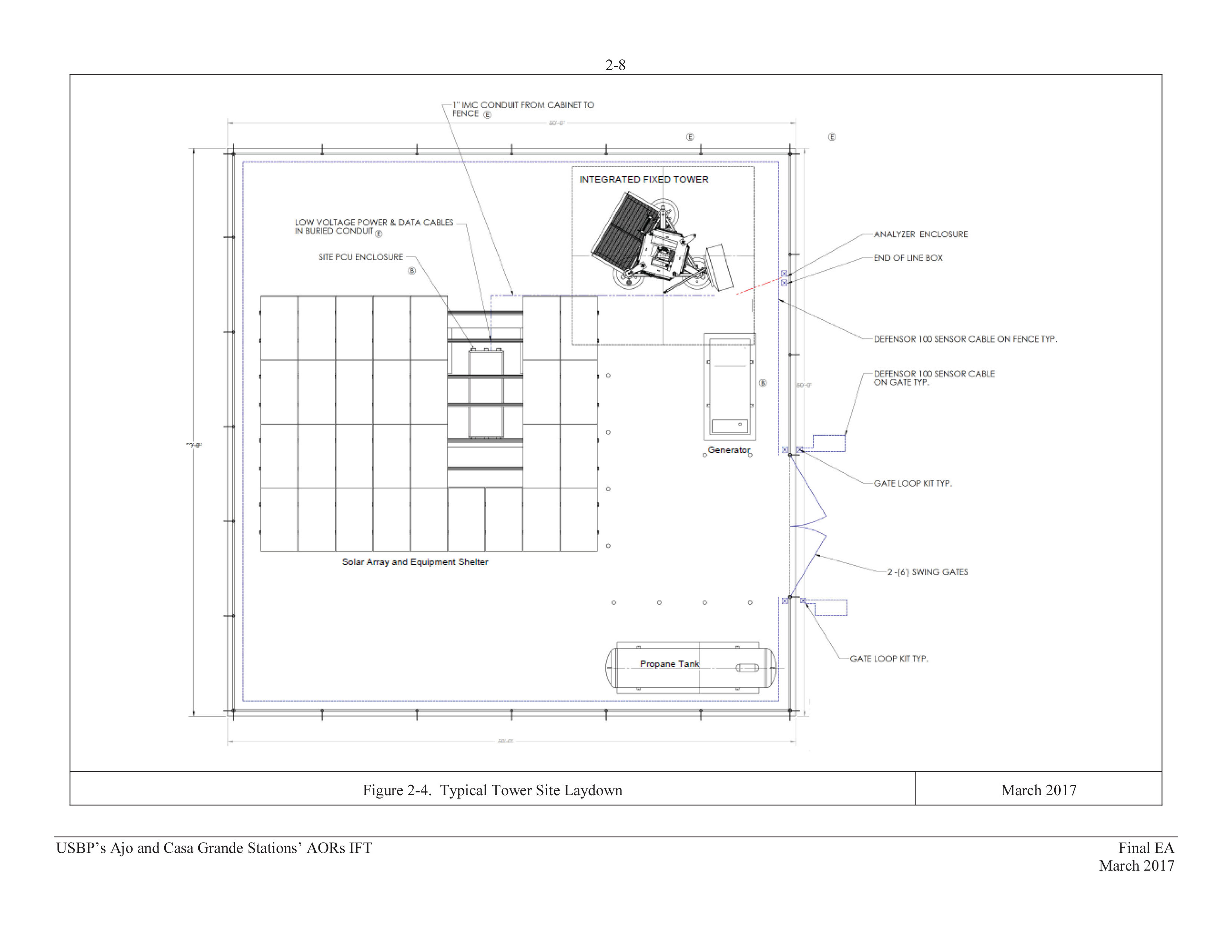

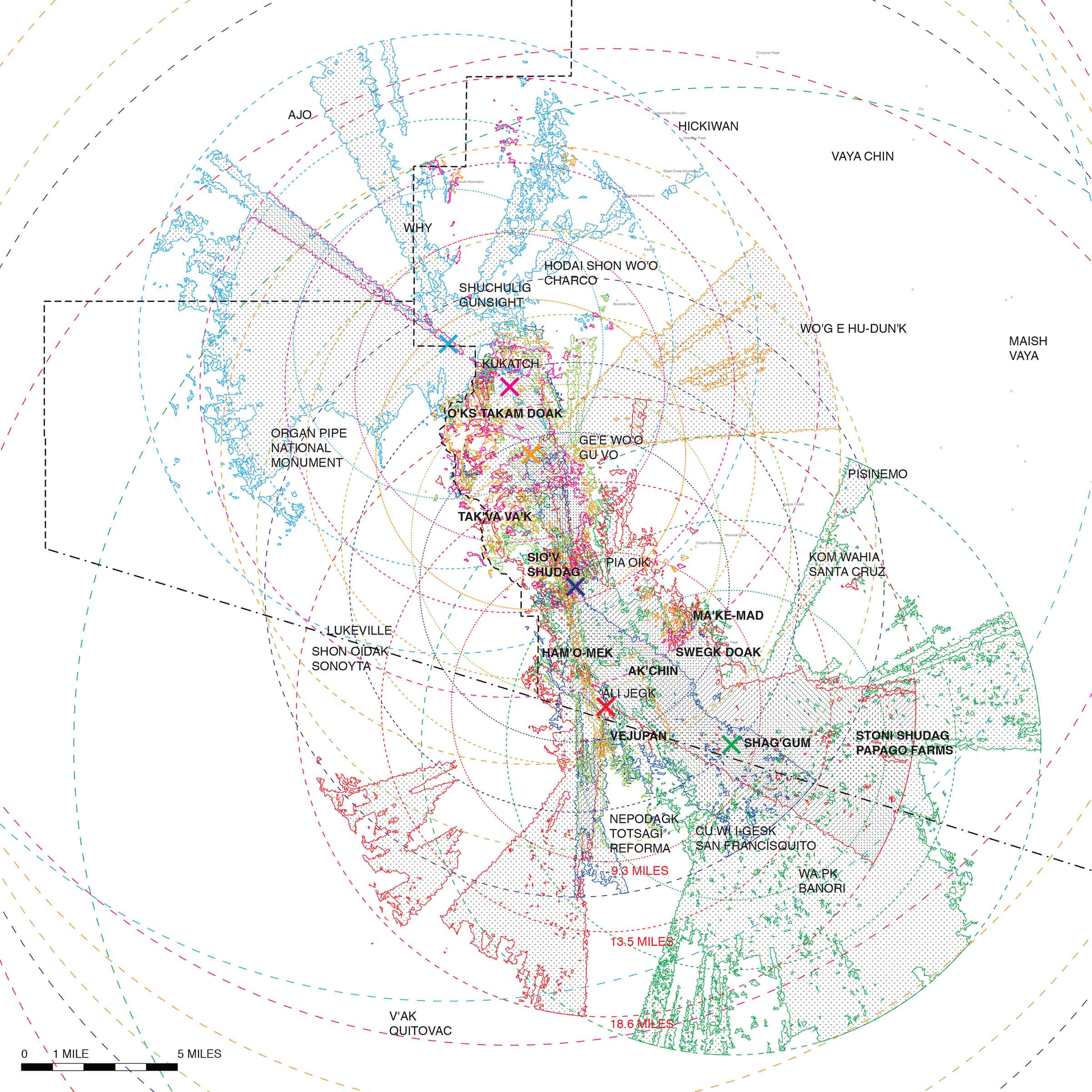

Unlike tribal gates, the proposed IFTs will not only operate on the international boundary. They are to be laid out in a curve following the US–Mexico border before turning at its juncture with the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and extending along the Tohono O’odham side of the border north into the interior of the United States. Trussed columns standing 120 to 180 feet high, they are mounted with surveillance equipment at the top and include a base with a propane tank, generator, solar panels, and equipment shelter. Their footprint is anywhere from 50 by 50 to 160 by 160 feet wide and includes a parking area. They are surrounded by a fence that would enclose up to ten thousand square feet and a thirty-foot-wide fire buffer beyond that where all vegetation is cleared. Tower access will also include seventy miles of new and widened access roads along with drainage ditches. They are then hooked up to the grid, necessitating new power lines and fiber-optic cables.7

But the real footprint of the towers extends beyond the perimeter of the fence, and even beyond the roadways that connect to it, in the shadow of the sensory and communicative data that flows through them. They will be outfitted with a range of surveillance equipment designed to identify and classify “items of interest” near the border. This includes radio-frequency radar that can detect moving bodies within a 9.3-mile radius, long-range video cameras to capture everything within a range of 13.5 miles, another radio-frequency radar that can detect moving vehicles within an 18.6-mile radius, and microwave communication receivers that transmit up to forty miles. In addition to that, they hold spotlights and laser illuminators for night operations.

Where radar, cameras, and lights are able to capture movement and presence, communication systems and dirt roads facilitate pursuit. Strategically flanking the Sierra de Santa Rosa mountain range, in O’odham Tak-Va’Vak, that divide the park from the reservation, the towers rely on the region’s geography for maximal surveillance and visibility. Visibility is essential not just as a vantage point over land but also as a “line of sight” for transmissions. In order for microwaves to reach from one tower to the next, each must be aligned in an unobstructed path. For comprehensive video and radar feeds, the radii of their range must overlap. And they do so extensively, reaching beyond the US–Mexico border into Tohono O’odham traditional lands in Mexico.

It’s no coincidence that the proposed construction of towers coincides with the addition of detention facilities for people apprehended crossing the border—one, in fact, constructed near the gate at Woo’san. It also requires little stretch of the imagination to understand that the infrastructure apparently needed to support construction and maintenance of towers (the truck paths latticing the desert, the movement of Border Patrol Officers to nearby stations, the tracts of housing and trailers of mobile offices) are also quite useful in the pursuit of “items of interest”—be they local residents, US citizens, or migrants entering the country legally or illegally. They are also part of a sustained harassment of the permanent population in the borderlands. This harassment is exercised at increasing scales, sometimes erupting into lethal violence. In addition to the CBP-regulated gates on the border itself, officers at checkpoints at the Nation’s border stop O’odham systematically. CBP pull people over at random driving on the reservation, raid their homes to see if they are helping migrants, and even draw guns on children running outside. They also have run over community members with patrol vehicles multiple times.8 With something close to one CBP agent for every ten registered tribal members, the land feels occupied, saturated with CBP agents and equipment. Both land and people are treated with hostility. This is “persistent surveillance,” and this pattern of harassment creates an infrastructure of state violence in which border militarization and policing of indigenous populations reinforce each other.9

Surveillance infrastructure is a continuation of the settler colonial project that seeks to dominate and control land on registers sensorial, physical, and epistemological: cameras and radar constantly image the landscape, bodies monitor movement on the ground, and documents like Environmental Assessments and Impact Statements dictate what the land and its use mean. Here, anthropologist Audra Simpson’s definition of “settled” is illuminating. For Simpson, the settled of settler colonialism refers both to the notion of establishing a population on a specific territory but also as “‘done,’ ‘finished,’ ‘complete’”—hence settlement is also the state’s monopoly on the making of meaning.10 In the case of the Department of Homeland Security, transforming terrain into a surveillance instrument dictates a meaning for land that is in direct opposition to an O’odham relationship to land, one in which the living and non-living are interconnected, in which knowledge comes through the experience of the land and the stories embedded in it, and in which that knowledge is itself an exercise of sovereignty.11

An infrastructure of surveillance—which includes patrolling bodies—and its attendant culture of fear has changed a tribal relationship to the land with significant cultural consequences. The towers, like the border fence and crossings, become agents of indoctrination, material mechanisms used to assimilate tribal members into Western culture with divisive consequences. The increased presence of Border Patrol Agents, for instance, has caused young O’odham to spend more and more time inside instead of out on the land. By claiming the tribal “common” land of the reservation as the space of surveillance and militarization—as property of the federal government and within its sovereign territory—border patrol forces tribal members into a space that they can more easily define as private property of their own: the house.12 By pushing tribal members into a lifestyle centered around private property, border surveillance not only has immediate consequences in terms of physical and psychological well-being (for instance, conversation with young people reveals how harassment has already been normalized among the youth), but it also ruptures intergenerational ties and spiritual knowledge and results in cultural disconnection to the land for its inhabitants.13 As tribal elder and activist Ophelia Rivas says,

Apart from the immediate consequences of surveillance, the fear and intimidation that turn community members to the home, according to Rivas there are longer-term effects—damaging an intergenerational connection to land and to cultural practices.

Environmental Agendas and Environmental Assessments

In April 2017, CBP published an Environmental Assessment stating that the Integrated Fixed Tower project will have no considerable impacts on the ecosystem or the tribe.14 This was the final step in the National Environmental Policy Act process that requires all federal agencies to conduct assessments when undertaking built projects. In an Environmental Assessment, a finding of impact can lead to an Environmental Impact Statement; however, CBP’s Assessment claimed any impact would be inconsiderable.15 As the widespread opposition to these towers by many tribal members and several traditional leaders shows, this is not the case. Residents of the tribal districts affected by the towers feel the towers’ presence would be catastrophically disruptive to ceremonial practices and daily life, as well as irreversibly destructive to a landscape they hold as sacred.

Traversing the desert was, and is, an integral part of O’odham time-keeping, connected to harvesting and hunting and to religious ceremonies. Mountains, valleys, and washes are known deeply, and the stories attached to them tell O’odham history; walking and running to sacred sites are spiritual acts and territorial practices; migration patterns determine hunting cycles. This unbounded mobility did not seem, in the eyes of white colonizers, aligned with the forms of settled subsistence farming so integral to the ideas of bounded private property on which governance in the United States is based.16 Political theorist Hagar Kotef argues that this idea of “excess” or “improper” movement led settler governments to sever the ties between indigenous populations and the land. Ideas of proper forms of movement and cultivation of land as property made expropriation and occupation seem more legitimate within the logics of the state and hence made it seem justifiable (though, in fact, just economically desirable) to impose rubrics of private property onto indigenous land that was held in common. In the case of the United States, this from of state thinking led to the reservation system, where the allotment of property to Native Americans was both an agent of containment and assimilation.

Following the Gadsden Purchase of 1854, which annexed thirty thousand miles of Sonora, Mexico, into the US—including O’odham territory—the government established two O’odham reservations in San Xavier and Gila Bend. The year 1887 marked the passage of the Dawes Act, which allowed the federal government to break up land on reservations held in common and divvy it into individual parcels granted to tribal members listed on official “rolls.” Remaining lands were open to settlers. While this did not happen on all reservations, Tohono O’odham lands were opened to allotment in 1888. In 1916, in response to the Mexican Revolution and Pancho Villa raids, the government created the Sells Reservation, now called the Tohono O’odham Nation, and built the first US–Mexico border fence on it.17 Then the fear was Mexican revolutionaries coming north into the United States, but implicit, too, was a need to imprint the idea of the American nation-state onto people for whom the border did not much matter. Thus began a history of federal incursions onto O’odham land (predicated on an even longer American and Spanish colonial legacy) in the name of defining and securing national property and hence national sovereignty. And, of course, the division of reservation land into allotments of private property has made it easier for the US government to claim eminent domain on non-allotted land within the reservation—which it has historically done to build infrastructure.18

But within this national sovereignty and its attendant regimes of property and security existed, and exists, another embedded one: indigenous sovereignty. Writing on Mohawk communities whose territory spans the Canada–US border, and on First Nations sovereignty more generally, Audra Simpson introduces the term “nested sovereignty” to describe the status of indigenous nations embedded within other nation-states. It is a complex and conflictual form of sovereignty, granted by the settler state, which understands the concept and rights it confers solely through Western political frameworks and which believes their citizenship to be de facto primary. As Simpson puts it,

Sovereignty may exist within sovereignty. One does not entirely negate the other, but they necessarily stand in terrific tension and pose serious jurisdictional and normative challenges to one another: Whose citizen are you? What authority do you answer to? One challenges the very legitimacy of the other. As indigenous nations are enframed by settler states that call themselves nations and appear to have a monopoly on institutional and military power, this is a significant assertion.19

And, following Simpson, as indigenous sovereignty challenges the authority of the military and administrative power of the United States, we see that it is not just the existence of an embedded sovereignty that threatens the settler state but also what sovereignty means and how it is exercised. The ways of knowing and being with territory—which is to say the ontological, cultural, and political forms of land use (including relationships among human and non-human beings)—that the O’odham exercise abrade Western, capitalist notions of sovereignty. It is these forms of interconnectivity that the Department of Homeland Security aims to undermine though technological, informational infrastructure.

In the draft Environmental Assessment, CBP justifies the towers on the basis of the landscape itself, arguing that “the difficult terrain and a lack of infrastructure within the Tohono O’odham Nation create a need for a year-round, persistent, technology-based surveillance capability that would effectively collect, process, and distribute information among USBP agents.”20 To counteract a terrain lacking in infrastructure, CBP is proposing to install a surveillance system that must tap into the very infrastructure they say the land is missing—roads, the electric grid, and fiber-optics.21 However, for O’odham this “difficult terrain” is, in fact, well known and well used; the landscape itself is full of signification that is disrupted by the introduction of militarized infrastructure.

Important to note here is a language that continues historic characterizations of indigenous land as underdeveloped and therefore in need of federal intervention.

In conversations with Rivas and other tribal members, one of the most offensive aspects of the towers is their physical appearance. Countless times we heard disbelief and indignation that these structures would be sitting on the mountaintop forever. Tak-Va’Vak is foundational to the O’odham origin story, hosting ceremonies as well as being visually integral to a sense of place. To impose a permanent technological, infrastructural, and militarized form of connectivity onto a symbol of connectedness to the land that has existed for the O’odham since the beginning of recorded history is an act with deep temporal gravity for this environment—affecting a relationship of life in the present to the past and the future.

Rivas recounts existing border patrol practices she fears will increase as this part of the mountain range is more closely monitored:

In Pisinemo—the district next to us—when they were doing their ceremony hunt, the border patrol surrounded them, tied their hands behind their back, and made them sit there until someone came and verified that they’re hunters on a ceremony hunt. That disturbs everybody. The people involved in the hunt, the women that are home praying for them and the deer, praying it will go well. It disturbs everything. For six years they didn’t get a deer because the border patrol was disrupting [the hunt]. Typically we go to ceremony, and after ceremony is over, they come around with the big baskets with deer meat and hand out deer meat for our blessings. It’s our spiritual food, our kind of energy food for the whole year, and for six years we didn’t have that, if you can imagine.22

Her fears convey not only the existing militarization of the Nation and violation of indigenous rights, but they also speak to the connectedness of ceremonial and social life, ecology, and landscape—an imbricated worldview that exceeds the compartmentalized and quarantining scope of the National Park Service’s conservation ideology and that has been disregarded by the preparers of the Environmental Assessment at ManTech, the “international corporation leading the convergence of national security and technology,” contracted by the Department of Homeland Security.23

A rigorous reading of terrain here allows us to see how it is deployed materially and conceptually by the US government and thus more deeply understand impact. Terrain is not simply the physical contours and geological composition of a landscape but also the built structures on it, the communities that use it, and the political regimes that govern it. In the words of Stuart Elden, “Terrain makes possible, or constrains, political, military and strategic projects, even as it is shaped by them. It is where the geopolitical and the geophysical meet.”24 Federal policing strategies originally used to contain and monitor O’odham people have been incorporated into Homeland Security tactics like Operation Gatekeeper, where terrain is not only used as a migration deterrent but also as a mechanism of territorial control. This has direct implications for O’odham lands, imposing one ontological system onto another. Sacred sites, the landmarks of origin stories, bedrocks of temporal and spatial knowledge, ceremonial grounds and hunting trails, ancestral burial sites and living habitats become armatures in the militarized reach of the state.

The repudiation of the tower project forces us to reassess not only how we, as people who work with and think about the built environment, talk about impact—it also pushes us to question on what basis potential sites for large-scale built projects are assessed and if the voices of affected communities can be heard in this process. In the case of the Environmental Assessment on the Integrated Fixed Tower project on the Tohono O’odham Nation, the numerous objections sent to the processing agency by tribal individuals and districts neither changed nor even found entry into the final document; however, the Tribal Council still has not approved the project, leaving it in a bureaucratic limbo.25 As of correspondence with Rivas in February 2018, CBP has apparently reduced the number of proposed towers to two, attesting to the effects of resistance. This is, of course, complicated by the proposed border wall, which the tribe opposes. What the tribe’s repudiation of the IFT project clearly does is question the distinction between action and inaction, between preservation and resistance, thereby undermining these binaries in a political act of refusal.26

-

“Integrated Fixed Tower,” International Towers Inc., link. ↩

-

This estimation was made by the authors by comparing historical and contemporary maps. ↩

-

These issues of cross-border mobility were relayed to the writers during an interview with Verlon Jose, vice chairman of the Tohono O’odham Nation, on December 12, 2015. ↩

-

For more on the complexities of tribal membership laws and standards of parental lineage or blood quantum requirements for membership, see Audra Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across Settler States (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014). For more on the politics of ancestry and tribal enrollment, see Kim TallBear, Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013). ↩

-

Formerly there had been five crossing gates. See Tay Wiles, “A Closed Border Gate Has Cut Off Three O’odham Villages from their Closest Food Supply,” Pacific Standard, February 7, 2019, link. ↩

-

See Joseph Nevins, Operation Gatekeeper: The Rise of the “Illegal Alien” and the Remaking of the US–Mexico Boundary (New York: Routledge, 2001). ↩

-

See “Final Environmental Assessment for Integrated Fixed Towers on the Tohono O’odham Nation in the Ajo and Casa Grande Stations’ Areas of Responsibility; US Border Patrol Tucson Sector, Arizona; US Customs and Border Protection Department of Homeland Security Washington D.C.” (April 2017), link. ↩

-

Some of these instances were recounted to us by community members. More information on Border Patrol violence, and the hit-and-runs specifically, can be found on the webpage of O’odham activist group TOHRN, link. See also John Washington, “‘Kick Ass, Ask Questions Later’: A Border Patrol Whistleblower Speaks Out about Culture of Abuse against Migrants,” the Intercept, link; and Bayan Wang, “‘Justice Needs to be Done’: Mom of Man in Video Showing Border Patrol SUV Strike Him,” AZCentral, link. ↩

-

The exact number of agents was not made available in interviews at the Ajo station, and this figure is a rough estimate based on data available for the entire Tucson Sector. For Tohono O’odham Nation population see “Districts,” Tohono O’odham Nation website, link, accessed August 20, 2018. ↩

-

Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus, 11. ↩

-

We are also thinking here of Elizabeth Povinelli’s term “geontopower”—a set of “discourse, affects, and tactics used in late liberalism to maintain or shape the coming relationship of the distinction between Life and Nonlife.” Elizabeth Povinelli, Geontologies: a Requiem to Late Liberalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 4. ↩

-

For more on mobility, property, and liberalism, see Hagar Kotef, Movement and the Ordering of Freedom: On Liberal Governances of Mobility (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015). ↩

-

Much of our research was done through conversations with O’odham members in the communities that will be affected by the towers during visits to these sites from 2015 to 2017, as well as in conversations with O’odham activist groups and tribal leaders. We also held a workshop with students from the Tohono O’odham Community College and Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation where tribal activists and leaders gave presentations to the students who worked on collaborative mapping projects about surveillance landscapes on the Nation and in the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Their perspectives have also been illuminating.

Land has always been defined by Europeans as properties. [CBP] have a different perspective on land, and so from that perspective, it’s very difficult for them to understand our relationship to it. I’m saying that because I’ve seen the reaction of the border patrol when we talk about our land and how we’re connected to it. It seems not to make a difference to them that it’s of great concern to us. It’s very disturbing to the people who continue to follow that ceremony way of life. … When I grew up, I climbed all these mountains and we ran and played all over. There were also people crossing the border that were undocumented. There was always drug trafficking, but we played everywhere. And now the kids are just stuck in their homes. It seemed it changed our whole way of life. It impacted it ever since this constant surveillance began. And when it began after 9/11, it was so aggressive that it forced the people not to go out on the land anymore. And that is really affecting the health of everybody. The health of the elders—who really need to be out on the land to connect with the plants and with the mountain. From that point on, the children don’t see their elders out there; they’re not connecting to that part of our life. This forced disconnection to the land is unhealthy because with the disconnection they lose their language, traditional diet, and sensitivity to turn to traditional medicine.[^14]

-

See “Final Environmental Assessment for Integrated Fixed Towers.” ↩

-

Of course Environmental Impact Statements are equally problematic, as the upholding of the “no impact” finding of the EIS for the Dakota Access Pipeline, following a legal injunction for the Army Corps of Engineers to reappraise it, attests Jan Hasselman, “On the US Army Corps’ Aug. 31 Decision on the Dakota Access Pipeline,” Earth Justice, link. ↩

-

See Kotef, Movement and the Ordering of Freedom. ↩

-

For more on the history of the Tohono O’odham borderlands, see Geraldo L. Cadava, “Borderlands of Modernity and Abandonment: The Lines within Ambos Nogales and the Tohono O’odham Nation,” Journal of American History, vol. 98, no. 2 (September 2011): 362–383. ↩

-

On the relationship between the history of federal infrastructure projects, current neoliberal infrastructure projects, and indigenous resistance, see Nick Estes’s recent book on the Dakota Access Pipeline and the Standing Rock water protectors. Nick Estes, Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance (New York: Verso, 2019). ↩

-

Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus, 10. ↩

-

“Draft Environmental Assessment for Integrated Fixed Towers on the Tohono O’odham Nation in the Ajo and Casa Grande Stations’ Areas of Responsibility,” (April 14, 2016), 25, link. ↩

-

Incidentally, the Bureau of Indian Affairs pays for the upkeep of roads that are worn down by the frequent traffic of CBP vehicles and equipment. ↩

-

Interview with Ophelia Rivas, December 13, 2016. ↩

-

Stuart Elden, “Legal Terrain—the Political Materiality of Territory,” London Review of International Law, vol. 5, no. 2 (July 2017): 25. ↩

-

As of conversations with Tohono O’odham chairman Edward Manual and vice chairman Verlon Jose on December 21, 2017. ↩

-

Audra Simpson has theorized refusal as a move that rejects the strictures of settler colonial bureaucracy in favor of exercising indigenous sovereignty. “Refusal,” as she says, “comes with the requirement of having one’s political sovereignty acknowledged and upheld, and raises the question of legitimacy for those usually in the position of recognizing.” Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus, 11. ↩

Caitlin Blanchfield is a doctoral candidate in architectural history at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation and an editor of the Avery Review. Her research explores questions of landscape and sovereignty in the Americas.

Nina Valerie Kolowratnik is an architect and researcher developing notational systems in the context of forced migration and cultural claims to territory. Since 2014 she has been teaching graduate courses on borderlands and counter-narratives at Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, and TU Vienna.