Banal clichés about “love against hate” cannot mask the concrete materiality of a paycheck signed in blood.

—S. Robert, member of the Community Coalition Against a Pulse Museum (CCAPM)1

A Converted Lounge and Renovated Nightclub

The drab, nearly fifty-year-old concrete block building at 1912 S. Orange Avenue used to house an Italian restaurant known for its $1.50 basket of garlic bread sticks. But by July 2, 2004, Lorenzo’s had been converted into a posh gay martini bar and lounge by Rosario Poma, Barbara Poma, and Ron Legler.2 Nestled between an electrical substation and a former gas station and car wash, and across the street from a Wendy’s fast food restaurant, Pulse was a lively new enterprise in a dour business district on the outskirts of downtown Orlando. While the novelty of Pulse was a source of immense excitement, the city’s newest gay bar had a much more profound impact in that it resuscitated my optimism for a delightful queer future. During the previous year, my favorite nightclub, Club Firestone, had stopped marketing itself as a gay venue—a disappointing entrepreneurial decision that for me signaled the inevitable death of gay leisure spaces. However, just when I thought gay bars were disappearing, Pulse opened and revealed that their potential remained.

Shortly after Pulse opened in 2004, I went there for my first time with my best friend. Considering its unremarkable exterior, the building’s renovated interior was unexpected. When we entered Pulse, the main lounge’s pristine, all-white decor lit up like a Christmas tree. The room changed colors as LED lights emitted different hues of the rainbow throughout the room. “Oooooh, this is fancy. It feels like we’re in Miami. Like we’re not even in Orlando anymore.” As we explored the venue, we walked between small cliques of gay men who were standing around, sipping on their drinks. We made our way to the back bar, the “Jewel Box” where people were moving alongside go-go dancers to Nina Sky, Destiny’s Child, and Christina Milian. It was the room for us.

During my senior year at the University of Central Florida, my friends and I went to Pulse at least twice a week. Every Wednesday was College Night, when we could get in free with our college ID’s; and “Pulsate” Saturday was the most popular night of the week, when you could also get in for free if you arrived before 11:00 p.m. If I could avoid being charged a cover, I was there. When townhomes were built next door, my friends moved into one of them, and whenever we would hang out together, we would end up going to Pulse for a few hours just because it was right across the street. It was at Pulse that I met the first go-go dancer I ever had a crush on, along with one of the friendliest bartenders I have ever known. With Orlando’s gay scene largely defined by a dive bar, hotel, and dance club—Savoy, Parliament House, and Southern Nights, respectively—as an “ultra-lounge” and martini bar, Pulse provided an alternative space for LGBTQ+ people to drink, dance, and mingle.

I eventually left Orlando for graduate school, and when I returned in 2011 there was much to rediscover. Many of the bars and clubs I frequented in my early 20s were still open for business, including Pulse. But when I revisited it, I became disoriented upon walking in. There was a new vestibule with a reception desk where someone stood to collect cover charges; the once gleaming lounge was completely redone to include a new bar, large stage, expanded dancefloor, and new seating; the bathrooms had been remodeled; and there was a new outdoor bar and seating area enclosed with a six-foot-tall vinyl fence.3 I again became a regular.

The Interim Memorial

On June 12, 2016, the mass shooting at Pulse left forty-nine people murdered, fifty-three others wounded, and more than two hundred additional survivors. At the time, it was the deadliest mass shooting in modern US history and remains the deadliest attack on LGBTQ+ people in the country.4 Occurring on “Latin Night,” those in attendance were Latinx “economic refugees” of the Puerto Rican debt crisis, immigrants, LGBTQ+ people of color, and their allies.5 Consequently, the majority of victims were LGBTQ+, Latinx, and black, with families of choice and origin in and from Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and Mexico disproportionately affected.6

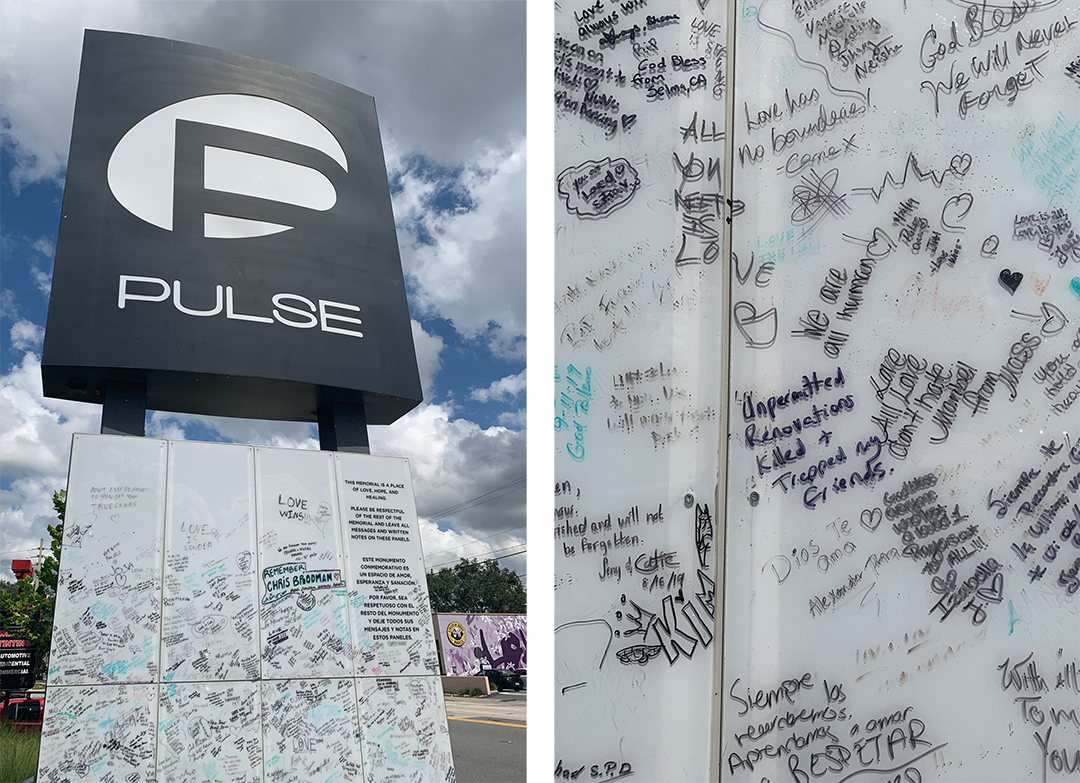

Nearly two years later, on May 8, 2018, the interim memorial on the Pulse nightclub property opened to the public. Funded by the onePULSE Foundation, the nonprofit organization founded by Pulse nightclub co-owner Barbara Poma, the interim memorial was designed by the landscape architecture firm Dix.Hite and was built while the foundation developed a plan for a much larger, permanent memorial/museum complex.7 The interim memorial’s main feature is a “ribbon wall” of photographs that wraps around the nightclub. When I visited it for the first time, I was surprised that none of the photographs depicted the victims of the shooting, instead showing responses to it that included people holding candles, hugging, standing together and smiling, and wearing “Orlando Strong” apparel. Advocate David Ballard criticized this focus on communal grieving and remarked, “Looking at it, I felt like I was witnessing theft.”8 Similarly, I felt as though I was looking at a serpentine billboard advertisement, where high-definition rainbows and smiling faces were being used to sell the nonprofit’s misleading slogan, “We Will Not Let Hate Win.”9 Missing were the esoteric expressions of grief and mourning that comprised prior, impromptu memorials on the site: letters, poems, toys, statues, grainy photographs, artwork, baked goods, posters, sculptures, flags representing the places where victims were from, clothing items, and flowers. These had been collected by the Orange County Regional History Center to be documented, cataloged, and stored for future exhibitions, only to be replaced with a sanitized façade that obscured the profound impact of the tragedy.10

Sections of the ribbon wall are made of glass so that the inquisitive can gawk at bullet holes, the boarded-up opening created when law enforcement had to breach the building to get to the remaining hostages, or the restored fountain wall that was broken on the night of the shooting—evidence of violence that is overwhelmingly triggering for many survivors and victims, but that provides death tourists the opportunity to bear witness.11 There is also a list of forty-eight victims’ names on the nightclub building along with a decal on the glass that separated the viewer from the structure that read, “Out of respect for the family’s wishes, a victim’s name has been kept private.” Less than fifteen feet away is a retail kiosk that sells T-shirts, a digital guestbook used to track marketable visitor data, and signs in both English and Spanish with rules for being on the property.12 A private security guard walks the premises, which is under constant surveillance, to enforce the memorial’s rules and remind people that they are on private property—a practice that on my visit felt intrusive, offensive, and disturbing.13 A small, sparse “offering wall” is allotted for visitors to leave items, and the Pulse Nightclub road sign was turned into an illuminated message board that people can write on using provided markers.

The Proposed Memorial/Museum Complex

Just over one year later, on May 30, 2019, the onePULSE Foundation released the designs for the proposed National Pulse Memorial and Museum drafted by six finalists in the onePULSE Foundation’s International Design Competition. Each of these teams were promised $50,000 honoraria for their shortlisted design submissions.14 These designs included plans for an expansive “Pulse District” that showcased the memorial/museum complex as an urban renewal initiative promising to develop the surrounding area, which largely consists of midcentury strip malls, small businesses, fast-food chains, and warehouses; a Pulse music label with recording studios in the “museum”; and a design for the memorial showing 268 columns crammed onto the nightclub property to represent survivors of the mass shooting.15 All of the designs were required to incorporate three main features: (1) a memorial built on privately owned property, (2) a private museum, and (3) a pedestrian pathway to the Orlando Regional Medical Center and downtown, called the Survivor’s Walk.16

Five months after these designs were released to the public through the foundation’s website and an exhibit at the Orange County Regional History Center, the winning design concept was announced at an invitation-only gathering held at 10:30 a.m. on a Wednesday. Business attire was required.17 The chosen design was drafted by a team that included Paris-based architecture and urban planning firm Coldefy & Associés, architecture and interior design firm RDAI, Orlando-based HHCP Architects, artist Xavier Veilhan, dUCKS scéno (a company that specializes in scenography and museography), landscape design practice Agence TER, and Professor Laila Farah of the Gender and Women’s Studies department at DePaul University in Chicago.18 They were chosen by a fifteen-person jury that included Orlando mayor Buddy Dyer, former president of Walt Disney World George A. Kalogridis, and eminent domain lawyer Earl Crittenden, who also served as the City of Orlando’s chief protocol officer—an appointee of Mayor Dyer.

The onePULSE Foundation assured the public that the designs were only a “starting point for discussion,” and discussion has certainly followed. Critics immediately remarked that the design for the museum was “too grandiose” and flashy, resembling a cooling tower of a nuclear power plant.19 Others suggested that aerial perspectives made the structure look like a giant shoe and compared it to the never completed Majesty Building, which also stands adjacent to Interstate 4 and is colloquially known as the “I-4 Eyesore.”20 These criticisms were separate from the larger movement against the onePULSE Foundation and its memorial/museum project organized by a group of survivors, family members of murdered victims, and activists collectively called the Community Coalition Against a Pulse Museum (CCAPM), with which I have been actively involved.21 Rather than focus on design criticism, CCAPM has called into question the legitimacy of the onePULSE Foundation, challenged its leadership, condemned turning the mass shooting into a new source of revenue, and rejected the privatized memorial/museum complex altogether.22 Furthermore, the CCAPM has collectively called for a public memorial park, similar to those built in response to mass shootings in Aurora, Colorado; Las Vegas, Nevada; Columbine, Colorado; and Newtown, Connecticut; as well as a mass shooting survivor assistance center to be built in place of a museum that would provide lifetime support to mass shooting victims from around the country.23

The onePULSE Foundation’s National Pulse Memorial and Museum has been championed by the Nonprofit Industrial Complex in an effort to legitimize it while reaping social, political, and financial benefits.24 Representatives from nationally prominent nonprofit organizations, notably those with political and educational missions that are LGBTQ-related, have banded together to silence local dissent through efforts to control public discourse while making claims that the memorial/museum complex will heal a number of problems affecting the LGBTQ+ community, such as suicide, hate crimes, and youth homelessness.25 At the same time, publications like the Advocate have declined to publish perspectives critical of the onePULSE Foundation’s proposal while circulating articles and opinion pieces that promote the project.26 While these tactics have been temporarily and intermittently effective in propping up the onePULSE Foundation and the project, they have been ineffective at concealing the web of violence that connects personal experiences with global instabilities.

The Neoliberal Nightmare

The struggle mounted by the Community Coalition Against a Pulse Museum in opposition to the onePULSE Foundation’s proposed memorial/museum complex is an extension of similar grassroots oppositional movements against private memorial museums that have taken shape elsewhere in the United States in response to public tragedies, such as the Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum and the National September 11 Memorial and Museum—both of which served as models for the National Pulse Memorial and Museum. Furthermore, their leadership teams served as advisers to the onePULSE Foundation.27 The Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum was originally established as a public project run by the National Park Service. However, it was eventually privatized due to declining attendance and rising costs—a move that angered many survivors and victims’ families.28 Funds raised for survivors ended up being directed to the museum, and even scholarship funds sparked backlash from victims.29 Similarly, the National September 11 Memorial and Museum, which was also modeled after Oklahoma City, continues to be criticized by victims for its “crass commercialism,” price of admission, gift shop, cocktail parties, and on-site restaurant.30

The rejection of the privatized memorial/museum complex by victims of violence has not yet been sufficient to prevent these lucrative projects from being built and from financially benefiting a select few. The spread of the private memorial/museum complex represents one way in which memorialization practices have been successfully co-opted by the hegemony of global capital, while mass murder, trauma, and grief continue to be exploited by those in positions of power.31 The onePULSE Foundation has stated that it plans to use its complex to attract visitors to Orlando “in traditional off-seasons … including, the highly sought-after LGBTQ community.”32 Such tourist opportunities are built upon violence that has disproportionately affected LGBTQ+ people of color, even in the spaces considered as sanctuaries. Public records show that Pulse’s renovations—the same modifications I observed when I returned to Orlando in 2011—were unpermitted. For years, the remodeled nightclub was never brought into compliance or shut down by the City of Orlando, which put all of the nightclub’s patrons at needless and ultimately fatal risk during that time.33 On June 12, 2016, the United States’ political and economic dependence on perpetual crisis in Latin America and perpetual war in the Middle East brought Latinx people and an armed shooter together at a gay bar in Central Florida, with horrific outcomes.34 In the aftermath of the shooting, low-wage nightclub workers who needed second jobs to get by required immediate access to donated funds as their employment provided them with no financial safety net.35 Survivors continue to struggle with medical debt, securing reliable mental health care, and emergency financial needs resulting from injury and lasting emotional trauma.36

Thus, the ongoing transformation of the property at 1912 S. Orange Avenue not only shows how LGBTQ+ life, trauma, and grief have shaped the urban landscape; it shows how these forces are shaped by capitalism as well. Specifically, the past, current, and proposed architectures of Pulse demonstrate how buildings, cultural institutions, and municipal districts are manufactured and constrained by the neoliberal agenda—in this case, the extraction of private profit by publicizing and exhibiting the losses suffered by LGBTQ+ people of color.37 Thus, despite the claim that not-for-profit “philanthropic” work ameliorates the harms suffered by minority communities, this patronizing governing logic in fact reproduces and deepens the systemic injustices of white supremacy, heterosexism, “gore capitalism,” and national chauvinism in a redistribution of public resources away from those for whom it is literally a matter of survival and repair, to those whose interest lies in the commodification of the murder of queer people of color, in perpetuity.38 Less discernible in the built environment, however, are the undercurrents of resistance that have only appeared, so far, as informational flyers, easily erased handwritten messages, and images and text shared on digital platforms. But this path for architecture, at Pulse and beyond, is not yet set in stone.

-

Community Coalition Against a Pulse Museum, “Who We Are,” 2019, link. The author is an active member of CCAPM. ↩

-

Alma J. Hill, “Looking Back on a Gay Nightclub that Almost Wasn’t; Looking Forward after the Massacre,” Watermark, June 8, 2017, link. ↩

-

Christal Hayes and Caitlin Doornbos, “Pulse Fence Was Not Permitted, but City Never Issued Citation,” Orlando Sentinel, July 23, 2016, link. ↩

-

The following year, the shooting at the Route 91 Harvest Festival in Las Vegas that occurred on October 1, 2017, eclipsed the Pulse massacre as the deadliest mass shooting in modern US history. Doug Criss, “The Las Vegas Attack Is the Deadliest Mass Shooting in Modern US History,” CNN, October 2, 2017, link. ↩

-

Laura Rodriguez, “The ‘Sacredness’ of a Latino Theme Night at Pulse and Other Gay Bars around USA,” Chicago Tribune, June 12, 2018, link; Juana María Rodríguez, “Voices: LGBT Clubs Let Us Embrace Queer Latinidad, Let’s Affirm This,” ABC News, June 16, 2016, link. ↩

-

“NPR Special Audio Coverage: Orlando Nightclub Shooting,” NPR, June 17, 2016, link; John Paul Brammer, “Digging into the Messy History of ‘Latinx’ Helped Me Embrace My Complex Identity,” Mother Jones, May/June 2019, link; Ed Morales, Fantasy Island: Colonialism, Exploitation, and the Betrayal of Puerto Rico (New York: Bold Type Books, 2019); Javier Arbona, “Queer Boricua Geopolitics and the Pulse Shooting,” U.C. Davis website, June 25, 2016, link. ↩

-

Dix.Hite+Partners, “Portfolio: Pulse Interim Memorial,” link. I use the term “memorial/museum complex” to refer to the proposed “urban campus” that the onePULSE Foundation has sought to create, which is inclusive of a memorial on the Pulse nightclub property, a museum built on newly purchased property located at the intersection of Kaley Street and Division Avenue about half a mile away from the nightclub and a pedestrian walkway to downtown called the “Survivors Walk.” ↩

-

David Ballard, “We Can Choose How We Remember Pulse,” Talk Poverty, June 14, 2018, link. ↩

-

A slogan that positions the tragedy as a hate crime to solicit LGBTQ donors is not only misleading; more fundamentally it has been used to position criticism of the foundation’s exploitative practices as “hate,” a cynical move that insulates the nonprofit through its fabricated associations of “love.” See Jane Coaston, “New Evidence Shows the Pulse Nightclub Shooting Wasn’t about Anti-LGBTQ Hate,” Vox, April 5, 2018, link; Adam Goldman, “FBI Found No Evidence that Orlando Shooter Targeted Pulse Because It Is a Gay Club,” Washington Post, June 16, 2016; and “Orlando Survivor: Gunman Tried to Spare Black People,” CBS News, June 14, 2016, link. ↩

-

The Orange County Regional History Center is operated by Orange County and the nonprofit Historical Society of Central Florida Inc. The nonprofit received a grant for $30,972 from the Contigo Fund to help support the One Orlando Collection. See Orange County Regional History Center, “Museum Affiliations,” link; Keep the Pulse, “The One Orlando Collection,” Orange County Government Florida, link; and Matthew Peddie, “Curating Pulse Memorial Items, Three Years On,” WMFE, June 11, 2019, link. ↩

-

Brigitte Sion, Death Tourism: Disaster Sites as Recreational Landscape (Salt Lake City: Seagull Books, 2014). ↩

-

“Tourism Development Council Meeting: September 21, 2018,” Orange County Government Florida, link. ↩

-

Nicole Pusulka, “After Pulse Shooting, LGBT Folks of Color Worry about Increased Police Attention,” Code Switch (NPR), August 3, 2016, link; Eric Schlosser, “The Security Firm that Employed the Orlando Shooter Protects America’s Nuclear Facilities,” The New Yorker, June 27, 2018, link. ↩

-

Kate Santich, “Pulse Memorial Designs Range from Sublime to Curious,” Orlando Sentinel, October 9, 2019, link. ↩

-

“9 Investigates Whether Pulse Was Over Capacity Night of Shooting,” WFTV 9 (ABC), July 1, 2016, link. The largest development in the area in the past decade was a Super Target department store, surrounded by mid-rise apartment buildings and a parking garage. It was during the construction of this eat, live, and shop development that the area was branded as SoDo (South of Downtown). ↩

-

Sydney Franklin, “onePULSE Foundation Announces Competition for National Pulse Memorial & Museum in Orlando,” the Architect’s Newspaper, March 25, 2019, link. ↩

-

See “onePULSE Announcement of Winning Design Team,” Orange TV, October 30, 2019, link. ↩

-

See Coldedy & Associates Architects Urban Planners, “Home Page,” link; and Sydney Franklin, “Coldefy & Associés and RDAI win design competition for the National Pulse Memorial & Museum,” the Architects Newspaper, October 30, 2019, link. ↩

-

Comments pulled from Facebook and Twitter. See also “Pulse Memorial Too Grandiose, Flashy,” Orlando Sentinel, October 31, 2018, link. For winning design, see, “National Pulse Memorial & Museum International Design Competition,” onePULSE Foundation, 2019, (link: https://onepulsefoundation.org/international-design-competition](https://onepulsefoundation.org/international-design-competition text: link). ↩

-

Construction of the Majesty Building in Altamonte Springs began in 2001, but the Great Recession, a lack of funding, and interstate construction stalled its progress for nearly two decades. It was built to house the broadcasting studios of the religious independent TV station SuperChannel 55. Caroline Glenn, ““Eyesore on I-4” Tower Still Isn’t Done, in part because of I-4 Construction Mess,” Orlando Sentinel, August 23, 2019, link. ↩

-

When describing mass shooting “victims,” there is not a clearly defined and universally accepted lexicon. “Victims” often refers to those murdered, but sometimes more expansively refers to all those affected, including survivors and family members of those murdered. To differentiate, some have chosen to specify “surviving victims” and “murdered victims.” In this essay, I have employed the expansive use of the term “victim” and have provided additional specification when clarification is needed. ↩

-

See “Our Research,” Community Coalition Against a Pulse Museum, link. Also Christine Leinonen, “Orlando City Council: Stop Profit on Bloodshed,” Change.org, link. ↩

-

See Zachary Blair, “Reimagining a Public Pulse Memorial,” Orlando Sentinel, July 14, 2019 link; and Zachary Blair, “Are Tourism Dollars More Important than Pulse Victims?” Orlando Sentinel, October 2, 2019, link. ↩

-

See Yasmin Nair, “Should I Stay or Should I Go?” Current Affairs, February 20, 2019, link; and Incite!, “Beyond the Nonprofit Industrial Complex,” link. ↩

-

See, for example, Facebook posts made by Equality Florida, which included reposting a clip of Orange County school board chair Teresa Jacob’s claim that the museum would “save thousands of young people’s lives” by raising awareness of LGBTQ teen suicides, published November 1, link; comments made on Facebook and Twitter by volunteers and employees of other nonprofits, including the Dru Project and the Historical Society of Central Florida and, Sara Grossman, “Pulse Needs to Be a Museum, Not Rubble,” Advocate, July 19, 2019, link. ↩

-

Grossman, “Pulse Needs to Be a Museum, Not Rubble.” ↩

-

Anthony Gardner, “9/11 Memorial Staff Helps Orlando Memorialize and Heal after Pulse Nightclub Shooting,” 9/11 Memorial and Museum website, link. ↩

-

Howard Witt, “Estrangement at Memorial,” Chicago Tribune, February 16, 2004, link. ↩

-

See Serge F. Kovaleski, “Donations Provide College Funds for Children of Oklahoma Bomb Victims,” Washington Post, August 20, 1995, link; and “Oklahoma Disaster Relief Fund Under Fire,” NBC News, March 1, 2013, link. ↩

-

Abby Phillip, “Families Infuriated by ‘Crass Commercialism’ of 9/11 Museum Gift Shop,” Washington Post, May 19, 2014, link. ↩

-

See, Marita Sturken, Tourists of History: Memory, Kitsch, and Consumerism from Oklahoma City to Ground Zero (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2007). ↩

-

The onePULSE Foundation’s Tourism Tax Development grant application (2018) has not been published by Orange County or the onePULSE Foundation. It was accessed by the author through a public records request. See also Kate Santich and David Harris, “Pulse Documents Detail Memorial Plans, Expected Visitors, CEO Barbara Poma’s Salary,” Orlando Sentinel, June 19, 2019, link. ↩

-

Zachary Blair, “The Pulse Nightclub Shooting: Connecting Militarism, Neoliberalism, and Multiculturalism to Understand Violence,” North American Dialogues (2016), link. ↩

-

Jackie Wattles, “Pulse Nightclub Distributes $28,500 to Out-of-Work Employees,” CNN Money, June 30, 2016, link. ↩

-

See Steve Contorno and Monica Herndon, “Three Years after Pulse Shooting, Psychological Wounds Still Raw, ‘This Isn’t Something that’s Going to Heal Itself,’” Tampa Bay Times, June 12, 2019, link. ↩

-

I use the initialism LGBTQ+ to include straight-identifying heterosexual allies who were also victims of the Pulse shooting. ↩

-

Sayak Valencia, Gore Capitalism (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2018). ↩

Dr. Zachary Blair is an anthropologist whose work explores the imbrications of race, sexuality, and urban space. His most recent projects examine gentrification and gay neighborhood production in Chicago, as well as inequality and ecologies of urban development in Central Florida.