el pueblo no aguanta más injusticia

se cansó de tus mentiras y de que manipulen las noticias

tos los combos, los caseríos

somos nuestra milicia

–Bad Bunny, Afilando los cuchillos1

where white men with shotguns

shoot at consanguineous shells

they destroy like glass poppies.

they shoot everything:

the sea, the seagulls,

the stones,

the miniature volcanoes,

the deltas,

the passing cloud that resembles the enemy.

– Raquel Salas Rivera, a beach exists

La luna nueva en una colonia

avecina semillas como antídotos.

Hay que aprender a leer los matojos.

Esto no es un presagio.

—Mara Pastor, Matojos2

A Puerto Rican revolution was well underway when the trap artist-turned-political activist Benito Antonio Martinez Ocasio, known by his stage name Bad Bunny, got involved in the summer of 2019.3 He is pictured standing still, flag in hand, wearing a face mask and a plastic face shield. Using his immense popularity (with over 27 million Instagram followers, many of whom are young Puerto Ricans), Bad Bunny denounced a system that “has taught” the people “to stay quiet” and made them “believe that those who take the streets to speak up are crazy, criminals, troublemakers.”4 These words were disseminated through a series of Instagram videos, a call to “show them [the government] that today’s generations demand respect” and that the country “belongs to all of us.”5 Through his social media platforms and later through his music, Bad Bunny joined many groups of activists in a collective demand for new emancipatory imaginaries in Puerto Rico.

Led by Instagram, Twitter, Facebook Live feeds, and the sound of the cacerolazos (a collective sign of protest performed by banging pots and pans), the Puerto Rican summer set an ideological fire. A range of queer and trans-feminist activists—most notably Colectiva Feminista en Construcción, a platform that explores feminism as a political project that intersects with questions of class, gender, and race—was joined by students from the Universidad de Puerto Rico and a massive gathering of the general population.6 This series of clashes and confrontations with the authorities in the Puerto Rican capital called for the resignation of Ricardo Rosselló, then governor of the unincorporated US territory.7 The demonstrations began after Puerto Rico’s Center for Investigative Journalism published 889 pages of a private Telegram chat—a messaging app preferred by politicians around the world because of its end-to-end encryption—between Rosselló and eleven aides and members of his cabinet.8 “Telegramgate” or “Rickyleaks,” as it was colloquially known and hashtagged, disclosed sexist, homophobic slurs and remarks targeting colleagues, politicians, beloved icons like Ricky Martin, local activists, and even victims of Hurricane Maria.9

But Puerto Rico instead witnessed a different type of revolution that summer of 2019. This revolution was unlike the many wars and revolts linked to struggles for independence around the world, or even to the previous anticolonial struggles like the armed rebellion of the Grito de Lares in 1868.10 This revolution was not aimed toward changing the Estado Libre Asociado (Free Associated State) status that has kept the archipelago without democratic powers or control over its own economy for more than a hundred years since the United States occupation but rather toward cultivating an emancipatory and dignified rebelliousness that could cooperate within the seemingly perpetual limbo of Puerto Rico’s territorial status. While the clashes culminated in the first resignation of a leading politician in the history of the archipelago, a series of iconic images and sounds circulating through social media platforms and international news networks produced this other, alternatively revolutionary imaginary. The images featured protesters waving Rainbow and Black versions of the Puerto Rican flag, dancing and kissing under the tropical rain, twerking in sacred and public spaces. The sounds included dembow beats (the popular rhythm that forms the basis of reggaeton) as well as the revolutionary anthem Bad Bunny created together with artists Residente and iLe, in which he raps “let all the continents know that Ricardo Roselló is an incompetent, homophobic liar,” a track that joined others in the soundtrack of the Puerto Rican post-colonial revolution.11

Achille Mbembe argues in his Provisional Notes on the Postcolony that the postcolony is “made up of a series of corporate institutions and a political machinery which, once they are in place, constitute a distinctive regime of violence” and is “characterized by a distinctive style of political improvisation, by a tendency to excess and a lack of proportion as well as by distinctive ways in which identities are multiplied, transformed, and put into circulation.”12 On the other hand, according to Frantz Fanon, the “always violent phenomenon” of decolonization “is the veritable creation of new men,” a creation that “owes nothing of its legitimacy to any supernatural power; the ‘thing’ which has been colonized becomes man during the same process by which it frees itself.”13 For Fanon decolonization involves “a complete calling into question of the colonial situation,” a “putting into practice” of the familiar saying, “The last shall be first and the first last.”14 If the term anticolonialism describes the struggle against colonization or imperial forces, and decolonization is a continuous process of self-awareness, the post-colonial might instead make use of the distinctive characteristics of occupied territories to formulate alternative, critical, and fantastic scenarios.

Both building on and departing from Mbembe’s definition, the term post-colonial is used here to describe the potential fabrication of such fictional narratives and emancipatory imaginaries under the suppressive apparatus of colonized territories.15 In Puerto Rico, the post-colonial as a speculative act of making takes the place of the historical anticolonial struggle and reimagines global processes of solidarity and subsistence under an oppressive system.

Post-colonial San Juan

The summer of 2019 offered vivid post-colonial scenarios. While the peaceful protests marched through the streets and avenues of the Puerto Rican capital city by day, at night a different form of clash awaited the streets of Old San Juan. Masked women and men yelled their demands as the police barricaded the streets, throwing canisters of tear gas in the many daily attempts to destabilize the protests and justify arrests—a practice dating back more than a hundred years. Simultaneously a series of “cuir” (a phonetic translation of “queer” used in Spanish) protests like La Renuncia Ball (with voguing drag-queens) or Perreo Combativo (a twerking dance-off executed at the door of San Juan’s main Catholic cathedral) outlined the new ideological and aesthetic direction of a post-colonial imaginary. This imaginary posted both a sense of pure political power outside the usual channels of the state alongside expressions of sexual freedom and the formulation of an alternative iconography.16

A colonial city planned by former European powers, Old San Juan serves as the backdrop for a struggle closely linked to the archipelago’s subordinate relationship as an “unincorporated territory” to the United States. The maze of streets in the old city center provided with a vast array of circulation options for the protesters as they found ways to avoid being corralled by the police. From the street-facing balconies at the second and third level, neighbors advised the protesters while recording and updating about the whereabouts and tactics of the police. Throughout several weeks, the daily scenario consisted of more or less the same protagonists. On one side, a group of police officers, with helmets and face shields, stood between the protesters and the official residence of the governor. Appropriately titled La Fortaleza (The Fortress), this former military building was completed in 1540 as part of an effort to reinforce the island’s defensive architecture.17 On the other side, an unchoreographed group of masked protesters resisted in unison, denouncing a state apparatus whose sole mission has been to privatize services, organizations, and entire areas of the archipelago.18 At the same time, on the public squares where colonial figures have been canonized in the form of statues and monuments or across from the Catholic Cathedral, scantily clad bodies danced continuously to the beat of Afilando los Cuchillos and other reggaeton songs.

The protests created an alternative image of Old San Juan, a space that Puerto Rican writer Luis Othoniel Rosa characterized in his reflection of events as the “historical jewel of the local white elite and a symbol of the colony that is used as touristic propaganda for cruise ships.”19 A combination of masked protesters and queer dancers rendered subversive images of the protests that strikingly contrasted with a landscape ideologically charged with what Rosa calls a “weird nostalgia for a militarized past of indigenous extermination, black slavery, and extraction of resources to support the luxuries of the European crowns, that today belongs to the European and American tourists.”20 Because the post-colonial is only possible with a hint of “kynical” humor (to draw on a concept outlined by Peter Sloterdijk), it is not a coincidence that the images of the new imaginary, of the Perreo and the drag queens were forged with the colonial city as backdrop.21

In the battleground of the old city center, a new form of imagination puts on display the once-utopian possibility of a change to the heteropatriarchal, homophobic, violent, and corrupt regime. But while this scenario offers a speculative canvas on which to paint new forms of emancipatory practices, is it possible to create new pedagogies that not only share these subversive strategies but create new networks of solidarity? Is it possible to understand these recent events not only as the spontaneous anger of a subordinate territory but as part of a radical movement a century in the making? Would this revolution of queer, feminists, and students offer alternative models of worldmaking? Or perhaps, could a hundred-year-old model of dignifying rebelliousness offer the blueprint for a post-colonial emancipation?

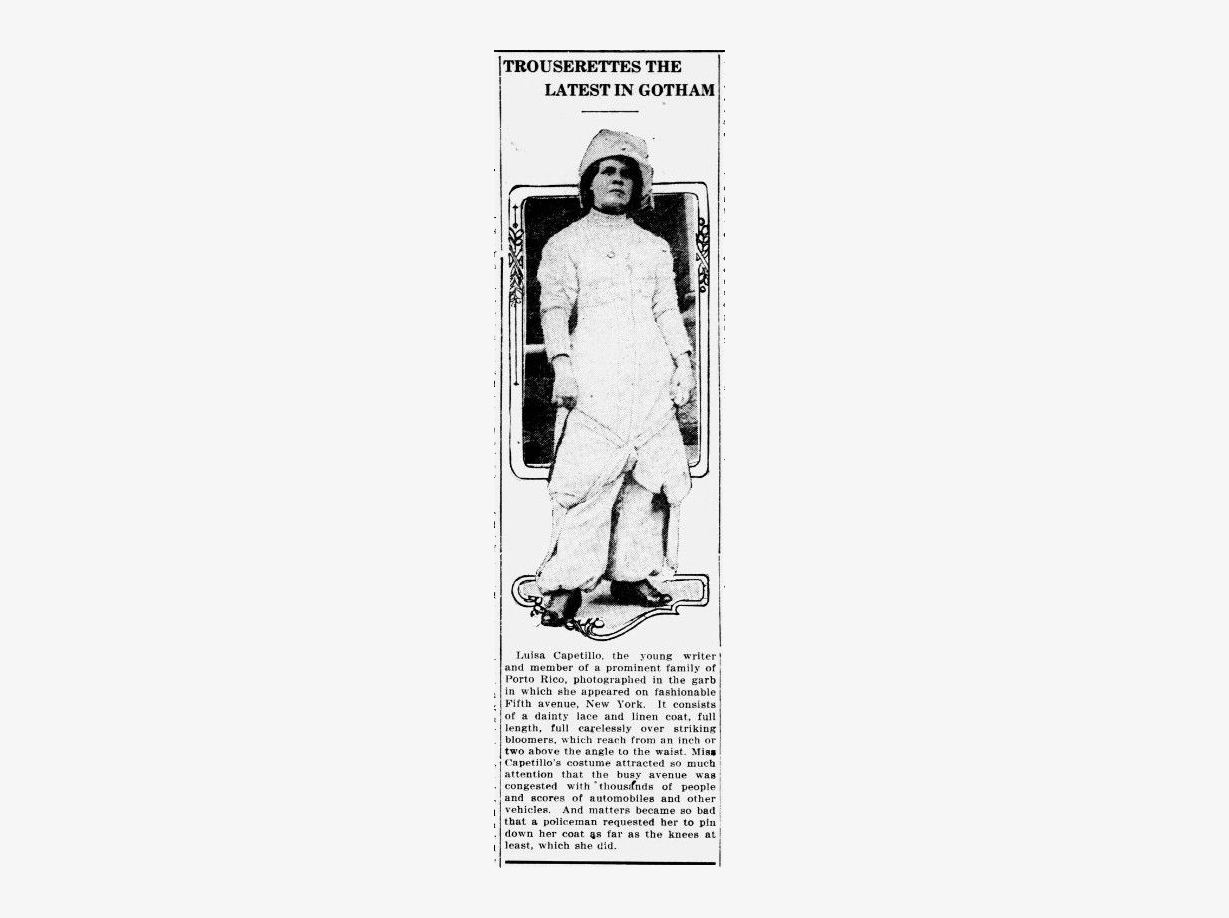

Lectores in 1919

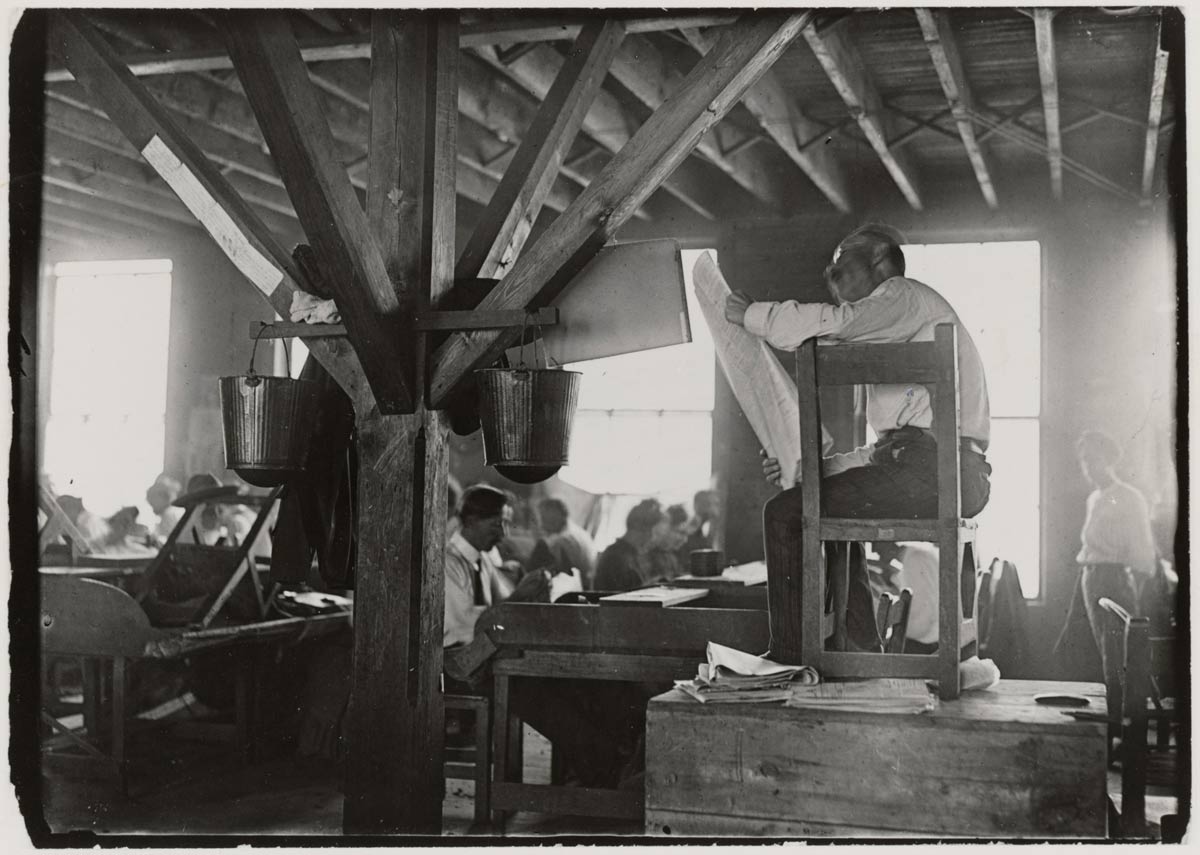

A century before the protests of the summer of 2019, a radical form of solidarity was performed around the main island of Puerto Rico. Led and inspired by Luisa Capetillo, a feminist anarcho-syndicalist arrested for wearing pants in public, a group of tobacco workers organized in syndicates, creating an alternative practice of education.22 The practice was simple. While tobacco workers engaged in the alienating labor of rolling cigars, they would hire one of their own to read out loud for them during the entire workday. As the practice of loudreading grew, the lectores (loudreaders) became traveling performers with an international audience, creating new networks of solidarity all around the Caribbean, as well as a massive, shared, and open access oral library to workers who were denied any other form of formal education. With readings that featured Pyotr Kropotkin, Charles Darwin, Mikhail Bakunin, Karl Marx, and Friedrich Engels, the literature that the lectores read for the workers shared an anticapitalist, decolonial body of thought.23 The tobacco workers turned the mind-numbing characteristics of their repetitive, manual, and boring work of rolling cigars into an advantage, using the same space and tools of their capitalist exploitation to create an anticapitalist underground culture.24

At first glance, the practice of the lectores might seem ironic: exploited workers at the bottom of the capitalist global machine producing tobacco, a highly addictive substance that generates more demand the more it is consumed, schooling themselves in an anticapitalist culture of liberation through revolutionary books (anarchists, feminists, communists), reading out loud while working for the same machine they are criticizing.25 From the perspective of the modern cynic, the lectores could seem to be secretly working for the tobacco corporations by making the workplace more bearable, selling the illusion of an anticapitalist society in order to make their capitalist machine more efficient, their exploitation inescapable. In this Huxleyean twist, the lectores would be selling a drug that would keep the workers hallucinating better worlds while being endlessly exploited in this one.

However, this was not the case. In a premonition of the post-colonial imagination, in 1910 Luisa Capetillo published La humanidad en el futuro (Humanity in the Future), a utopian tale centered around a central strike. Several years later, feminist, activist, and suffragist Juana Colón (the self-taught daughter of slaves) led a series of massive workers’ strikes that swept the tobacco factories, first in the municipality of Comerío and then around the main island, causing multiple arrests and deaths of protesters at the hands of the police.26 As the practice of loudreading stimulated the possibility of rebellion, other forms of solidarity were put in place by leaders of this movement like Dominica González, Concepción (Concha Torres), Genara Pagán, and Franca Armin. These actions challenged the mainstream male-driven workers’ organizations with feminist voices. Their practices included collecting comisiones (money and provisions for the striking workers), attending mítines, raising their voices during the tribunas to challenge the arguments being made by male speakers, and creating a network of support by providing food and clean clothing for workers imprisoned during the strikes.27

Laborers were not alone as the lectores masterfully combined suffragist movements, labor rights, feminist discourses, and anticolonial fights dating back to the abolishment of slavery (1873) and the US invasion and occupation of Puerto Rico (1898) as part of the Spanish–American War. For most, the incapacity to read became a bonding trait among workers unveiling new forms of emancipation through collectivity and mutual aid. As propaganda was distributed and loudreading fomented new networks of solidarity, spaces of oppression were transformed into architectures of subversion. A continuous landscape of social unrest expanded across mountains and valleys, plantations, refineries, and warehouses, in the sugar mills of Central Guánica, Central Aguirre, and Fajardo Sugar, the coffee plantations in Yauco, and under the cheesecloth of tobacco plantations in factories across Cayey, Comerío, Puerta de tierra, Gurabo, and Aibonito. As loudreading became a key form of pedagogy, lectores like Capetillo also published manifestos, magazines, pamphlets, and newspapers with emancipatory and utopian agendas.28 The creation of other forms of media to carry the message of emancipation can be traced back to its origins in La Habana of 1864, and extended from the Puerto Rican landscapes occupied by the American Tobacco Company to the rest of the Americas. As loudreading grew, international networks of solidarity blossomed into what some historians call the most enlightened proletariat force in the continent during the twentieth century.29 The practice subsequently became a target for the colonial authorities. Following its association with formal institutions like the FLT (Federación Libre de Trabajadores or Free Federation of Workers) and the Socialist Party, loudreading was systematically persecuted by American intelligence agencies, and the tobacco companies banned, illegalized, and persecuted lectores.30 The medium of the emancipating voice—so potent, accessible, and so different from the easily traceable material infrastructures of print media—was clearly understood by imperialist authorities as a threat to be neutralized.

Loudreading Artifacts and Their Centenary Ties

The pedagogical approach of loudreaders offers an alternative to canonical avant-garde institutions as well as the settler-colonial legacies of universities with their tainted endowments and land grants.31 Just as Bad Bunny and the Colectiva Feminista en Construcción use social media to create and foster networks of solidarity through alternative platforms, a new generation of performers has the potential to retake the role of post-colonial loudreaders in search of new forms of education. Like the lectores in the tobacco factories, new loudreaders would stand against the monumentality pursued by institutions in which knowledge has been evidently manifested in the construction of a centralized apparatus of physical buildings for schooling. Instead, loudreaders would share the spirit of decentralized agit-prop, spontaneous presentations, and anti-institutional rebelliousness. Loudreaders would establish networks of solidarity by every available form of free and accessible media. While being fueled by the energy in the streets generated by the many marginalized groups, loudreaders could continue a legacy of political installations and spatial artifacts to house new models of aesthetic and ideological iconography.

Following the shared histories of the lectores before them, in the contemporary manifestation loudreaders would organize around the decentralized, contemporary precarious labor force that is continuously disempowered, disenfranchised, and expropriated from its territories by means of forced evictions, foreclosures, privatization, and undemocratic legislation. Knowing that although Puerto Ricans have been US citizens since 1917, legal residents of the archipelago have no representatives in the US House or Senate and are unable to vote in presidential elections, loudreaders would strive to develop solidarity among global networks of struggle.32 Just as Capetillo and the original lectores found inspiration in the words of Kropotkin, Marx, and Cuban intellectual José Martí, the new imaginaries might draw connections between the moving propaganda of Nina Kogan’s designs for the trams in Vitebsk, the purple T-shirts of Colectiva Feminista en Construcción that read “Antipatriarcal, Feminista, Lesbiana, Trans, Caribeña, Latinoamericana”(Antipatriarchal, Feminist, Lesbian, Trans, Caribbean, Latin-American), and the motorbike and equestrian mass movements invoked during the Puerto Rican protests.33 In their push to establish contemporary connections and to reappropriate icons of the avant-garde, loudreaders might perceive connections between David Yakerson’s Supremaman, the chair in which Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano would seat to address the media, and the ad hoc installations made for the use of lectores inside the factories. A loudreading ontology of subversive strategies of political actions would create a material repertoire that oscillates between viral social media propaganda and the metal stands where Bad Bunny, rapper-activist René “Residente” Pérez, Ricky Martin, Ednita Nazario, and other Puerto Rican icons stood during the protests.

In addition to these strategies, in its aim to create ideological symbols, establish historical connections, and produce speculative scenarios under the pressure of the crisis, this post-colonial imaginary might turn Luisa Capetillo and Bad Bunny into icons of subversive political ambition. Such a post-colonial narrative might link the face mask and plastic face shield sported by Bad Bunny months before the global pandemic to the need to reclaim the pharmaceutical industry that comprises more than half of the archipelago’s manufacturing output.34 The same post-colonial imaginary would see the relationship between Luisa Capetillo’s iconographic shirt, tie, pants and short brim hat—that would cause her persecution in Cuba and Puerto Rico—to the advancement of women’s rights during the lectores era, in a practice mostly performed by men. These scenarios—Luisa Capetillo as queer lector and Bad Bunny as a post-COVID loudreader—render hopeful images of a post-colonial emancipation, as a new imaginary learns to operate within the politics of sexual oppression (in the first case) and death (in the second) in the middle of an unfolding crisis.

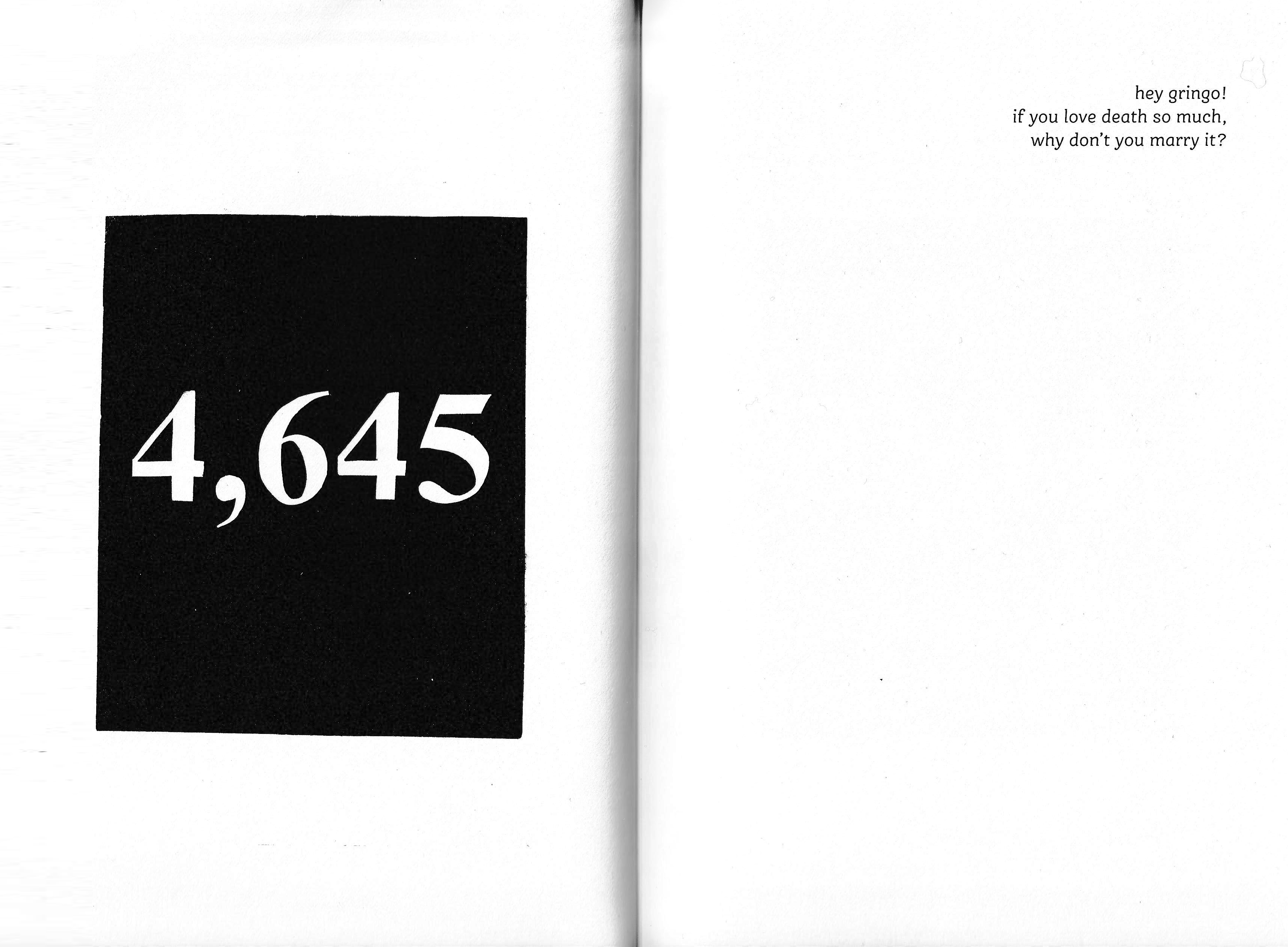

Loudreading within Necropolitics

Whatever form post-colonial loudreading takes in Puerto Rico, it will have to operate under a regime of death. Puerto Rico is in the midst of an unprecedented financial, environmental, ecological, and health crisis. While the first ousting of a governor in the five-hundred-year-old colonial history of the archipelago could be a sign of progress, the effects of a “gore” or “disaster” capitalism (to use the terms of Sayak Valencia and Naomi Klein)—which have been accentuated by Hurricane Maria, the recent sequence of massive earthquakes, and the ongoing pandemic of the novel coronavirus with the threat of an upcoming hurricane season—make an extreme cocktail of risk.35 But a post-colonial imagination has the potential to recognize that the condition of Puerto Rico as the world’s oldest colony can serve as an emancipatory model of what Mbembe calls the “becoming black of the world.”36 Not unlike how tropical atmospheric phenomena and health crises intensify and expand beyond the geographical limits of the tropics in a rapidly warming world, the “globalization of markets, the postimperial military complex, and electronic digital technologies” that the colonized south has long been subject to become the norm around the world. The “becoming black of the world” implies that “all events and situations in the world of life can be assigned a market value” and thus have turned “the systematic risks experienced specifically by Black slaves during early capitalism,” when “men and women from Africa were transformed into human-objects, human-commodities, human-money,” into the “norm for, or at least the lot of, all subaltern humanity.”37

Just as several American states are confronted with the deliberately orchestrated negligence of the federal government in the face of a still-developing health crisis, and a rising wave of confrontations between police forces and Black Lives Matter manifestations, violations of human rights and the slow response to disasters experienced in Puerto Rico have become an almost commonplace practice.38 In addition, with the ethos of war shifting from bellicose struggle to the fight against a global pandemic or against civil manifestations, we witness the operation of necropolitics. Per Mbembe, the contemporary forms of “subjugation of life to the power of death” and the implicit “reconfiguration among resistance, sacrifice, terror,” make the colonial condition of Puerto Rico a petri dish where the conditions of “repressed topographies of cruelty (the plantation and the colony in particular)” become normalized around the world.39

To deal with the Puerto Rican condition today is to deal with a global state of risk, impoverishment, debt, and environmental spoliation. In their relationship to the lectores, post-colonial loudreaders in Puerto Rico might operate with weary optimism and irony through the alternative futures of science fiction, and by means of the performative, poetic, and activist confrontations with the painful trails of the present. Among these, Luis Othoniel Rosa proposes Puerto Rico oscillating within seven centuries to imagine how through technological innovation and sheer will we may all become one thinking, feeling, solidary being. Rafael Acevedo outlines the ways to switch between sharp political commentary and poetry to organizing through social media posts the collective display of thousands of shoes in front of the Capitol building as a form of antinecropolitical protest to memorialize the lives lost after the hurricane. Ana Lydia Vega narrates a tsunami disappearing the archipelago in the Puerto Rican trench as the ultimate end of the cuitas of the colonial status, while the many busts of Martí—a revolutionary figure in the Caribbean—in Mara Pastor’s poem, speak to and over each other, drowning revolutionary voices in an inoffensive roar.40 To this series of post-colonial prototypes, Raquel Salas Rivera adds through poetry and activism, a new concept of the tertiary, not just as the Marxist theory of labor as the force that gives value to the commodities exchanged between two powers, but as the “third thing that gives value” between “colonialism and Puerto Rico, queer and transness, the binary of colony and empire.”41 Salas Rivera then follows with a poem that may as well be the ultimate post-colonial anthem of the necropolicital condition of the archipelago:

If the continuous state of crisis models Puerto Rico as the test bed for a global necrofuture, these loudreaders might render new post-colonial futurisms against and within the mantle of necropolitics and its politics of exploitation of the dead. In a world where the commodification of death is commonplace, the post-colonial loudreaders could articulate the “becoming Puerto Rico of the world.”

-

“The people can’t stand more injustice

They’re tired of your lies, and of the manipulation of the news

all the crews, social housing projects,

we are our own militia.”

Translation by the authors. ↩ -

“The new moon in a colony

foreshadows seeds as antidotes.

One must learn to read the bushes.

This is not an omen.”

Translation by the authors. ↩ -

Nuria Net, “Why Bad Bunny Wants Puerto Rican Youth to Take the Streets,” Rolling Stone, July 17, 2019, link. ↩

-

Net, “Why Bad Bunny Wants Puerto Rican Youth to Take the Streets.” ↩

-

Net, “Why Bad Bunny Wants Puerto Rican Youth to Take the Streets.” ↩

-

Glorimar Velázquez Carrasquillo, La Colectiva, o cómo construir un país desde el feminismo, ONCE, August 26, 2019, link. ↩

-

Ed Morales, “Feminists and LGBTQ Activists Are Leading the Insurrection in Puerto Rico,” The Nation, August 2, 2019, link. In characteristically vague terms, the US government classifies Puerto Rico as an unincorporated territory or “a United States insular area in which the United States Congress has determined that only selected parts of the United States Constitution apply.” See “Definitions of Insular Area Political Organizations,” Office of Insular Affairs, US Department of the Interior, link. ↩

-

Luis J. Valentín Ortiz and Carla Minet, “Las 889 páginas de Telegram entre Rosselló Nevares y sus allegados,” Centro de Periodismo Investigativo, July 13, 2019, link. ↩

-

Ray Sanchez, “These Are Some of the Leaked Chat Messages at the Center of Puerto Rico’s Political Crisis, CNN, July 17, 2019, link. ↩

-

“The so-called ‘Grito de Lares’ broke on September 23, 1868. The rebellion was planned by a group led by Dr. Ramón Emeterio Betances and Segundo Ruiz Belvis, who together in January 6, 1868, founded the Comité Revolucionario de Puerto from their exile in the Dominican Republic. Betances authored several proclamas or statements attacking the exploitation of the Puerto Ricans by the Spanish colonial system and called for immediate insurrection. These statements soon circulated throughout the archipelago as local dissident groups began to organize. Secret cells of the Revolutionary Committee were established in Puerto Rico bringing together members from all sectors of society, to include landowners, merchants, professionals, peasants, and slaves.” See Marisabel Brás, “The Changing of the Guard: Puerto Rico in 1898,” Library of Congress, link. For more info on the Grito de Lares, see “The Grito de Lares: The Rebellion of 1868,” Library of Congress, link. ↩

-

Net, “Why Bad Bunny Wants Puerto Rican Youth to Take the Streets.” ↩

-

Achille Mbembe, “Provisional Notes on the Postcolony,” Journal of the International African Institute, vol. 62, no. 1 (1992): 3–37. ↩

-

See Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Richard Philcox (New York: Grove Press Inc., 1963), 36–37. As Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang articulate, Fanon’s concept of decolonization needs to be put into question, particularly when it implies colonization as an allegory or metaphor. The “enactment of these tropes,” Tuck and Yang argue, “problematically attempt to reconcile settler guilt and complicity, and rescue settler futurity.” Among the moves to innocence these authors identify: settler nativism, fantasizing adoption, colonial equivocation, conscientization, at risk-ing / asterisk-ing Indigenous peoples, and reoccupation and urban homesteading. We reference Fanon’s approach to the decolonial subject here in its capacity to identify an ongoing process that relates the continuous putting into question of the colonial condition. See Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vol. 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40. ↩

-

Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, 36–37. ↩

-

While Achille Mbembe describes the condition of the “postcolony,” our use of a hyphenated version, post-colonial, implies the fabrication of a fictional narrative on the future state of a current colony while alluding to a series of identifiable traits on former (or current) colonial territories. ↩

-

See Luis Othoniel Rosa, “Pensar en panal. Apuntes sobre las protestas masivas en Puerto Rico, Julio 2019,” Ediciones Mimesis, August 7, 2019, link. Translation by the author. ↩

-

La Fortaleza and San Juan National Historic Site in Puerto Rico, UNESCO, link. ↩

-

A bill introduced in 2016 to address Puerto Rico’s debt crisis aimed to enable the sale and private development of thousands of acres in the Vieques National Wildlife Refuge, an island municipality that was formerly occupied by the US Navy as training ground. Will Rogers, “Puerto Rico’s Problems Shouldn’t Be Solved By Selling Public Lands,” HuffPost, April 6, 2016, link. See also Sherrie Baver, “Environmental Struggles in Paradise: Puerto Rican Cases, Caribbean Lessons,” Caribbean Studies, vol. 40, no. 1 (2012): 15–35, link. ↩

-

Rosa, “Pensar en panal.” ↩

-

Rosa, “Pensar en panal.” ↩

-

“Kynical” is used here in reference to an architecture that employs irony and humor as forms of ideology critique. Kynical as opposed to cynical is a reference to the philosophical school founded by Diogenes of Sinope as described in Peter Sloterdijk, Critique of Cynical Reason (Minnesota: Minnesota University Press, 1983). ↩

-

Taru Spiegel, “Luisa Capetillo: Puerto Rican Changemaker,” Library of Congress, November 18, 2019, link. ↩

-

Araceli Tinajero, Luisa Capetillo: Lectora en Puerto Rico, Tampa y Nueva York, El Lector de tabaquería: Historia de una tradición cubana (Madrid: Editorial Verbum, 2007), 169–180. ↩

-

Luis Othoniel Rosa and Post-Novis, “The Tobacco Intergalactic School, Introduction to the Syllabus ‘The Tobacco Intergalactic School (Postnovis Branch in the Americas),’” February 1, 2019–February 1, 2031, in Post-Novis Manifesto, 2019, link. ↩

-

Contains parts from Rosa and Post-Novis, Post-Novis Manifesto, 2019, link. ↩

-

For more on Juana Colón, see the scholarship of Bianca M. Medina Báez, Wilson Torres-Rosario, and Aurora Levins Morales. ↩

-

Jorell A. Meléndez-Badillo, “Imagining Resistance: Organizing the Puerto Rican Southern Agricultural Strike of 1905,” Caribbean Studies, vol. 43, no. 2 (July–December 2015): 53. ↩

-

Tinajero, Luisa Capetillo, 169–180. ↩

-

For more on the influence that the lectores had in the Caribbean, US, Mexico, and Spain see the work on of Tinajero, and Julio Ramos research on Luisa Capetillo. ↩

-

Among the strategies employed by American intelligence organizations, the FBI’s COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program) created more than 185,551 folios, and the local police documented a total of 16,793 dossiers and 151,541 reference cards as part of a massive, multidecade operation aimed at eliminating the Puerto Rican pro-independence movement and any potentially affiliated subversive organization. See Joel Blanco-Rivera, “The Forbidden Files: Creation and Use of Surveillance Files Against the Independence Movement in Puerto Rico,” the American Archivist, vol. 68, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2005): 297–311, 10.17723/aarc.68.2.n2ql6618n0267501; FBI Records, The Vault: Puerto Rican Groups, link; and Mireya Navarro, “New Light on Old FBI Fight; Decades of Surveillance of Puerto Rican Groups,” the New York Times, November 28, 2003, link. ↩

-

la paperson explains the relationship between settler practices and the creation of land-grab universities across the United States. See la paperson, “Land: And the University Is Settler Colonial,” A Third University Is Possible (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), link. For more on how the Morrill Act turned Indigenous land into college endowments see Frank Joyce, “The Settler Colonialism Project,” Counter Punch, April 24, 2020, link. ↩

-

At the end of the day the archipelago is a US territory without a legitimate or democratic “rights framework” since any “continuation or modification of current Federal Law and policy to Puerto Rico remains within the discretion of the United States Congress.” House Hearing, 105 Congress, From the U.S. Government Printing Office, United States-Puerto Rico Political Status Act, July 26, 1996, link. ↩

-

Spiegel, “Luisa Capetillo.” ↩

-

On the relationship between tax laws and the pharmaceutical industry in Puerto Rico see Avik Roy, “Puerto Rico Can Help the US End Its Dependence on Chinese Pharmaceutical Ingredients,” Forbes, March 16, 2020, link. ↩

-

See Sayak Valencia, Gore Capitalism (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018); Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (New York: Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt, 2007); and Klein, The Battle for Paradise: Puerto Rico Takes on the Disaster Capitalists (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2018). See also Achille Mbembe, Critique of Black Reason, trans. Laurent Dubois (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017). ↩

-

Since Puerto Rico was invaded on November 19, 1493, during the second voyage of Christopher Columbus, and has since then never been outside of the jurisdiction of another nation, an argument could be made that the archipelago is the world's oldest colony. See, among others, Rita Indiana, “Puerto Rico, the Oldest Colony in the World, Gives the World a Master Class on Mobilization,” the Boston Globe, July 26, 2019, link. See also Mbembe, Critique of Black Reason. ↩

-

Mbembe, Critique of Black Reason, 2–4. Mbembe references Walter Johnson, Soul by Soul: Life inside the Antebellum Slave Market (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999); Ian Baucom, Specters of the Atlantic: Finance Capital, Slavery, and the Philosophy of History (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005); and Joseph Vogl, Le Spectre du capital (Paris: Diaphanes, 2013). ↩

-

For a detailed study on the inequities of the federal response to hurricane disaster in Puerto Rico, see Charley E. Willison, Phillip M. Singer, Melissa S. Creary, and Scott L. Greene, “Quantifying Inequities in US Federal Response to Hurricane Disaster in Texas and Florida Compared with Puerto Rico,” BMJ Global Health 2019;4:e001191. See also the ACLU’s report "Island of Impunity: Puerto Rico's Outlaw Police Force, American Civil Liberties Union," June 19, 2012, link. As this paper is written, a series of manifestations spread across the country to denounce the killing of George Floyd. ↩

-

Achille Mbembe, “Necropolitics,” trans. Libby Meintjes, Public Culture, vol. 15, no. 1 (Winter 2003): 11–40. ↩

-

Cuitas in this context means “disgrace or affliction.” See Ana Lydia Vega, Puerto Rican Syndrome o Cosas extrañas veredes (Reportaje rescatado del maremoto que acabó con las cuitas del status), Encancaranublado y Otros Cuentos de Naufragio (Rio Piedras: Editorial Antillana, 1983), 39–49; and Mara Pastor, Los Bustos de Martí, Falsa heladería (Bayamón: Ediciones Aguadulce, 2018), 27–28. ↩

-

Claudia Irizarry Aponte, “A Conversation with Queer Boricua Writer Raquel Salas Rivera, Philadelphia’s Newest Poet Laureate,” NPR Latino USA, April 16, 2018, link.

hey gringo!

if you love death so much,

why don’t you marry it?[^42]

Cruz Garcia and Nathalie Frankowski are architects, educators, authors, curators, and co-founders of WAI Architecture Think Tank. In response to the global pandemic of COVID-19, they have been developing Loudreaders, a series of online sessions and a trade school exploring networks of intellectual solidarity. They are authors of Narrative Architecture: A Kynical Manifesto, and Pure Hardcore Icons: A Manifesto on Pure Form in Architecture.