When the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was written into law in 1990, it created a framework for the provision of access in most aspects of civic life. Except the ADA does not extend to air travel. Instead, the US aviation industry complies with a separate piece of legislation from 1986, the Air Carrier Access Act (ACAA). Both the ADA and the ACAA prohibit discrimination on the basis of disability, but the latter makes a major exception to this general nondiscrimination requirement.1 Air carriers have every right to “refuse to provide transportation to any passenger on the basis of safety.”2 Drawing in part on my own experiences, I want to think about how this legal exception becomes the rule for wheelchair users who travel by air. Our digital surveillance in the security process and physical probing during the boarding process are organized out of a concern for the safety and security of others. In practice, accessibility functions as the de facto right of others to access the disabled body.

Particularly since the creation of the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) in 2001, passengers with disabilities who pass through airport security have come to experience a strange algorithm of non-care. The ritual performances of non-care anonymize disabled people through the everyday practices of access and accommodation.3 This non-care comprises an important aspect of the jurisdiction of bodies and their compulsory adherence to the normative demands of gender, race, and disability. In a related analysis, design justice scholar Sasha Costanza-Chock has drawn attention to the “particular sociotechnical configuration of gender normativity (cis-normativity) that has been built into the scanner, through the combination of user interface design, scanning technology, binary gendered body-shape data constructs, and risk detection algorithms, as well as the socialization, training, and experience of the TSA agents.”4 Costanza-Chock draws on their lived experience to highlight the gender-conforming practices produced by data-dependent systems. According to these systems, gender follows a strict binary that generates normative values. Deviant bodies that break these normative rules are considered a risk and trigger further rounds of assessment from agents. People with disabilities often avoid a direct brush with this sociotechnical apparatus but not without experiencing the configuration of gender at another level.

I speak from lived experience. Held at the checkpoint, I hear “AGENT, WHEELCHAIR, FEMALE…” repeated until the called-for female volunteer arrives to perform the full-body search. Passengers with disabilities, particularly those who are unable to pass through the scanner because they are not designed to accommodate mobility devices, are automatically advanced to a manual search performed by the TSA agents. If data systems have an unconscious gender politics, disabled passengers’ exclusion from airport scanner devices also has a politics.

Disabled passengers’ exclusion from the data processing involved in scanning is not a reprieve from the policing of bodies. Instead we must reckon with the TSA agents’ attempts to generate and validate the “missing” technical data with intimate and invasive body searches. In these instances, the absence of data drives the rituals of air travel for some disabled passengers. This to say that the datafication of air travel has heightened the number and frequency of intimate searches in an attempt to replace the missing gaps in airport security datasets. The impartiality seemingly promised by data and AI is supplemented everywhere by the procedures of inspection and anatomization executed by TSA agents. The enactment of these security protocols begins with a checklist-like evaluation that accompanies the body search.

“Can you stand?” “I’m going to search behind your back.” “Can you lean forward in your chair?” “Are you able to shift your weight from side-to-side?” “I’m going to use the back of my hands to feel under your chest.” “Do you have any pain or sensitive areas?”

While progressing through their checklist, TSA agents first map their directions onto their own body. Adjusting their posture and pointing to their own anatomy, each one of them outline the body parts in question and map out the zones of imminent corporeal invasion. In this way they draw out an implicit geography of gender surveillance, performing security on and across the body, to underestimate and undervalue the private boundaries of disabled passengers. They touch me as they have just touched themselves. Not quite consent but not quite a violation of privacy either. Disability justice activist Mia Mingus has described the difficulty of such an encounter as a “forced intimacy.”5 Distinct from Mingus’s often-cited concept of “access intimacy,” forced intimacy refers to the unspoken expectation that disabled people suspend their personal boundaries in order to secure their own basic rights to access.6 Access intimacy, in contrast, reflects the centering of disability communities’ desires for the collective and consensual production of access. These forms of intimacy are incompatible.

Upon completion of the body search, another agent wipes down the black contours of the wheelchair for any residue of explosive chemicals. She proceeds to wipe my white sneakers as well. At each stage, she feeds the soiled swabs through a nearby machine to deliver real-time results. I’m cleared to leave the holding area. With every purchase of an airline ticket, with every flight, I ready myself to barter with my body for an accessibility built around a dependency on, and submission to, others. The everyday experience of interdependency gives way to a strange negotiation of artificial intimacies—the price paid to spend time with family and friends.

The indifference performed by TSA agents is caught up in the politics of labor. Their affective labor is complicated by the ritualization of impartiality—one that mimics the anonymity of surveillance data and the supposed neutrality of algorithms—as well as by the overriding “national security” interests they are designed to serve. “Do you have any pain?” “Can you stand?” These questions, perhaps driven by the need to fill in missing data, or to measure the lack of access, are uncanny. Elsewhere expressions of care or concern, they become perfunctory tasks in the hands and mouths of the agents.

The affective labor that goes into the security and assistance process shores up the biometric instruments’ failure to produce data about disabled bodies. Manual (usually gloved) contact with nonnormative bodies makes up for the inability of the security scanner to accommodate wheelchairs and other assistive technologies. Subjective assessments about my ability to navigate physical obstacles offsets the airport’s ignorance of its own accessibility. Verbal inquiries about my level of bodily distress compensate for the inability of any instrument to objectively measure pain. The algorithm of non-care therefore consists of the failure of the algorithmic process, producing informal data from forced intimacies that crowd out the possibility of care.

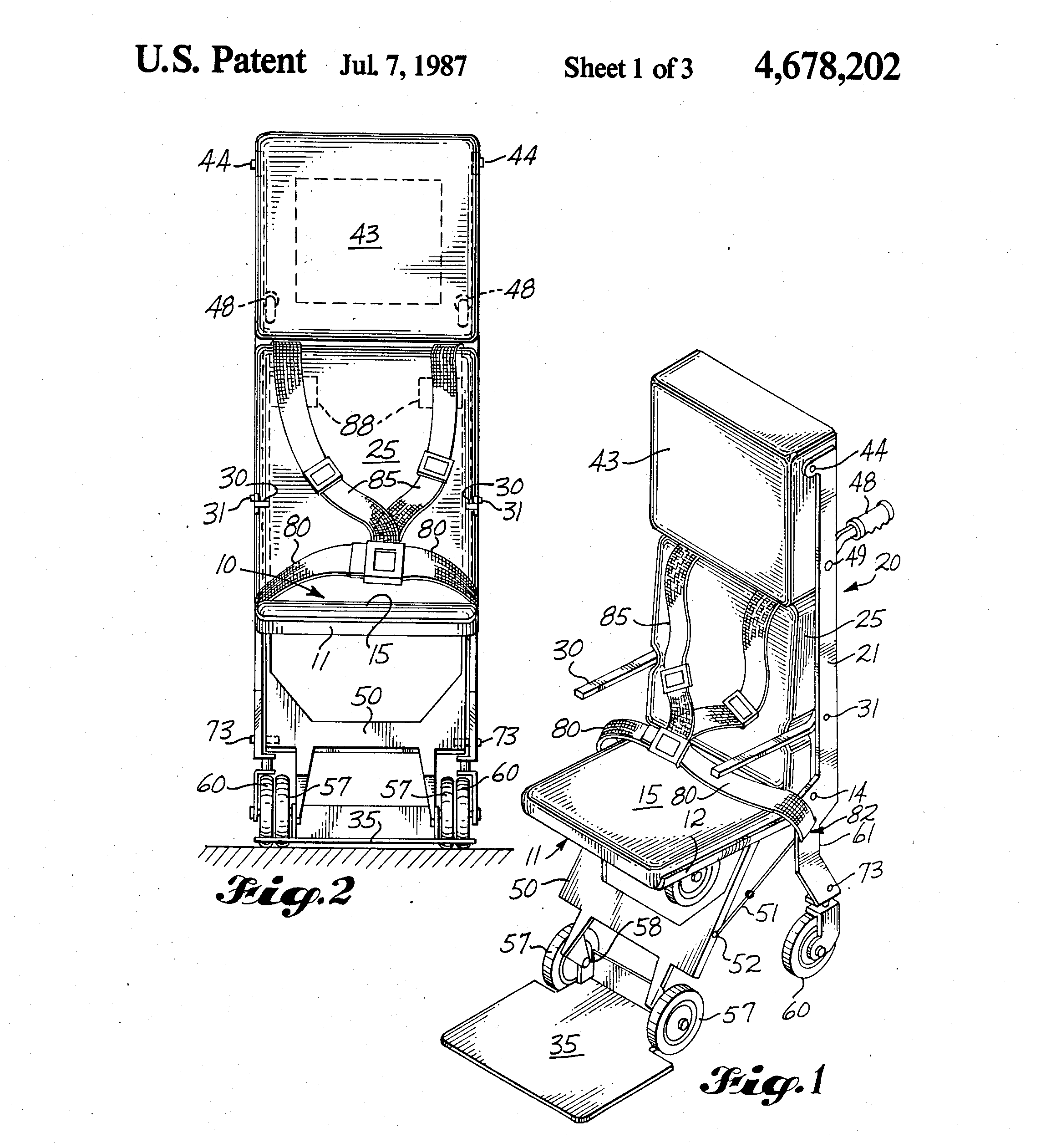

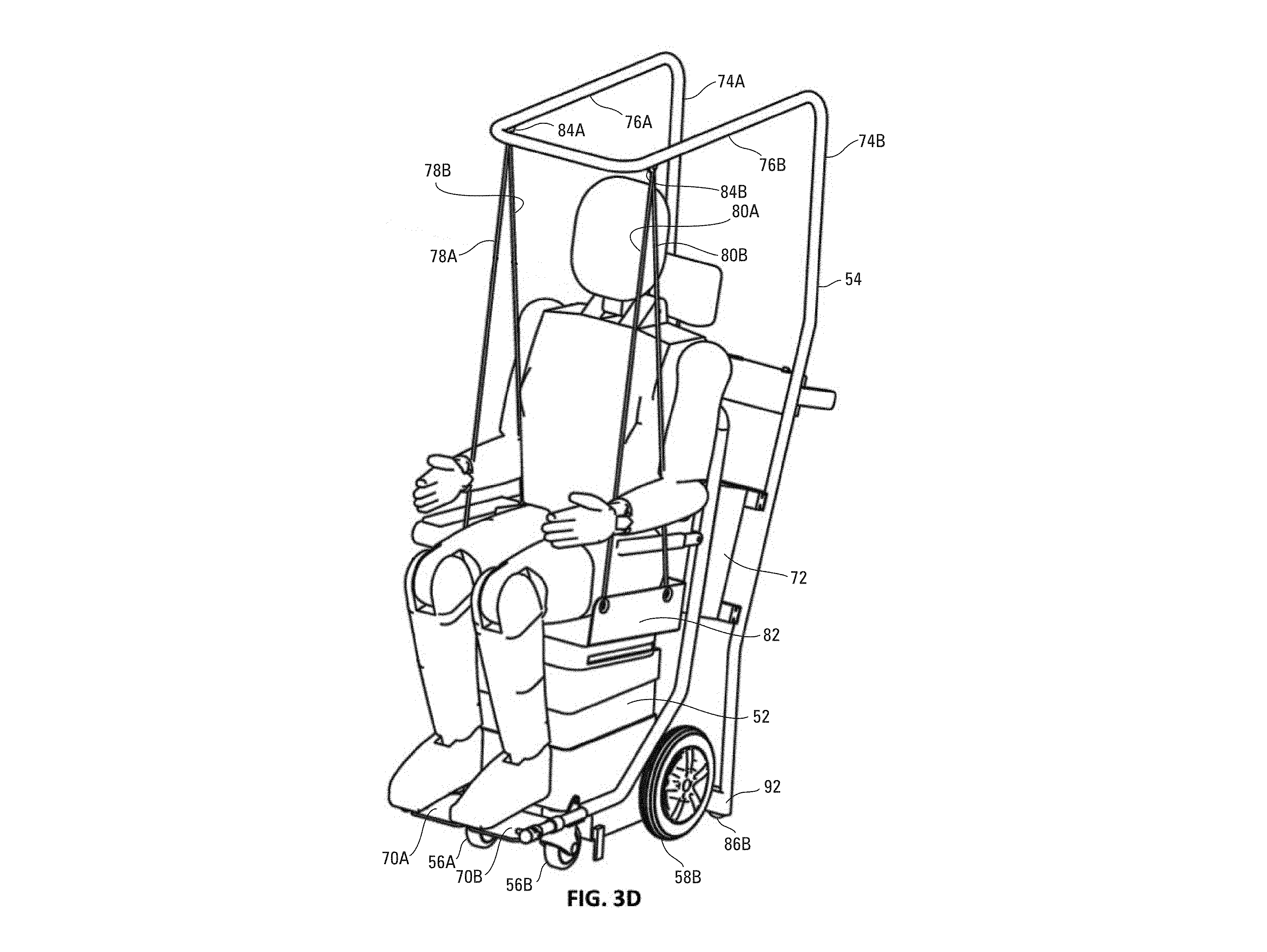

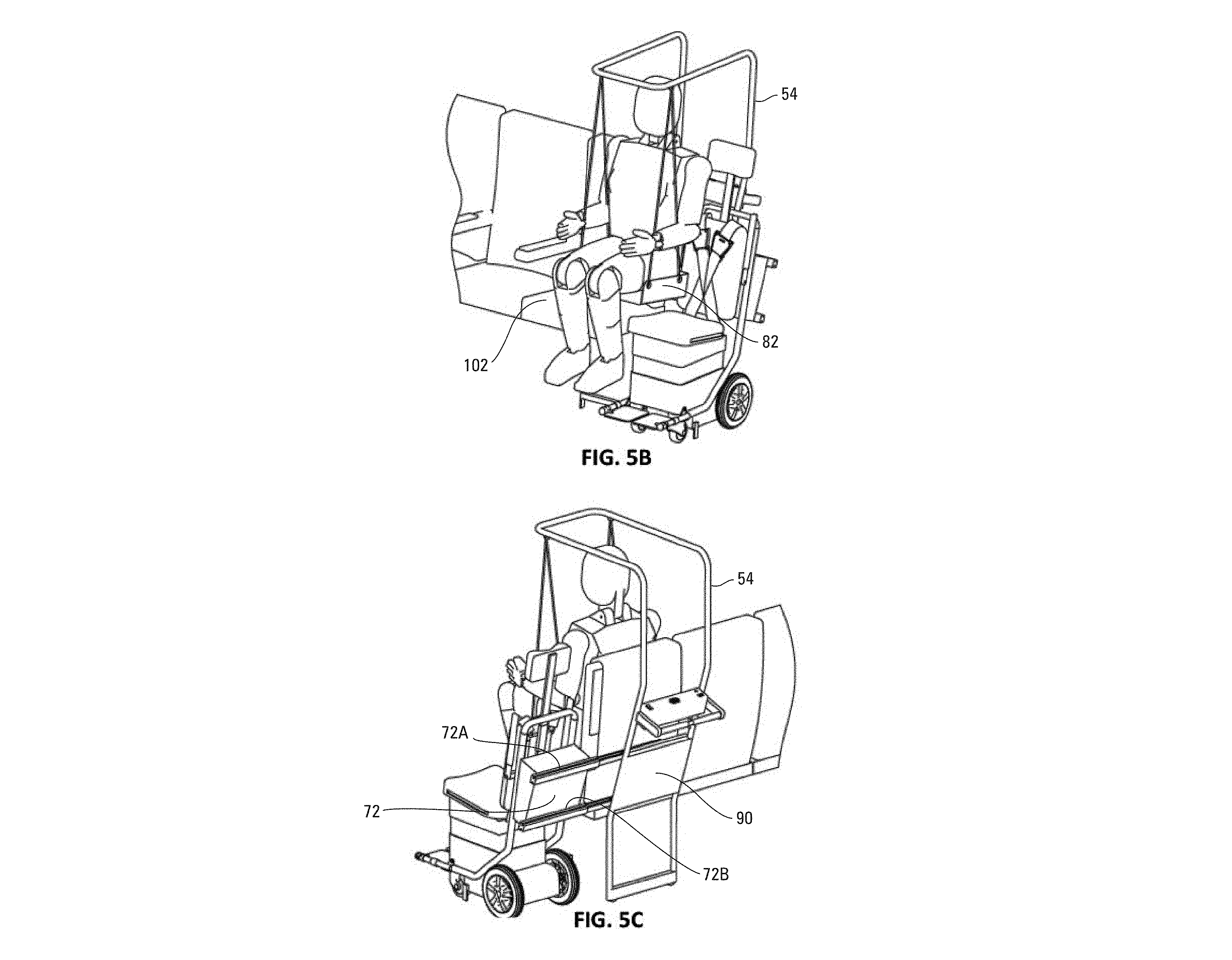

Whether boarding short- or long-haul flights, a strange hierarchy of abilities is first organized. An algorithmic attempt of sorting bodies out occurs before the departure gate even opens. Passengers who require “special assistance” are called to the front, where on-the-ground staff “sort out” passengers’ levels of impairments. An ad hoc triage system then gets implemented. Non-ambulatory passengers, slightly ambulatory passengers, and parents with small children form separate lines in preparation for the boarding process. At the entrance to the aircraft, a small collection of onboard wheelchairs, depicted in the figures here, is readied. The wheelchairs, relatively unknown devices to many passengers, are designed to carry non-ambulatory passengers to their allocated seat aboard the aircraft. The slender fit of the wheelchairs matches the aisle width to the rear of the aircraft, a notoriously compressed space meant to maximize additional inches for economy seating.

All flights arriving from, departing to, or transiting through the United States follow access guidelines set by the ACAA. The European Union has a similar law—Regulation 1107/2006—concerning the rights of disabled persons and persons with reduced mobility.7 Together these laws cover the majority of global airline travel. Yet vastly different interpretations of “the safety of others” and varying approaches to providing on-the-ground assistance, not to mention a lack of robust means of enforcing these laws, ultimately creates a patchwork system of practices and experiences. The lack of international coordination regarding access laws, even within the same air carrier, indicates the global disparities in the governance of disability and accessibility. The American and European protocol of moving from the personal wheelchair to the onboard wheelchair is itself an internally inconsistent practice subject to disparate on-the-ground provisions, in terms of both access hardware and access labor. The pressures of economic competition, the inconsistency of access laws, and the haphazard process of sorting bodies, all held together by the affective labor of airport personnel, combine to create an unspoken grammar of non-care that governs the practice of onboarding disabled passengers. Flashpoints of anxiety riddle the process and render the notion of accessibility both abstract and impossible.

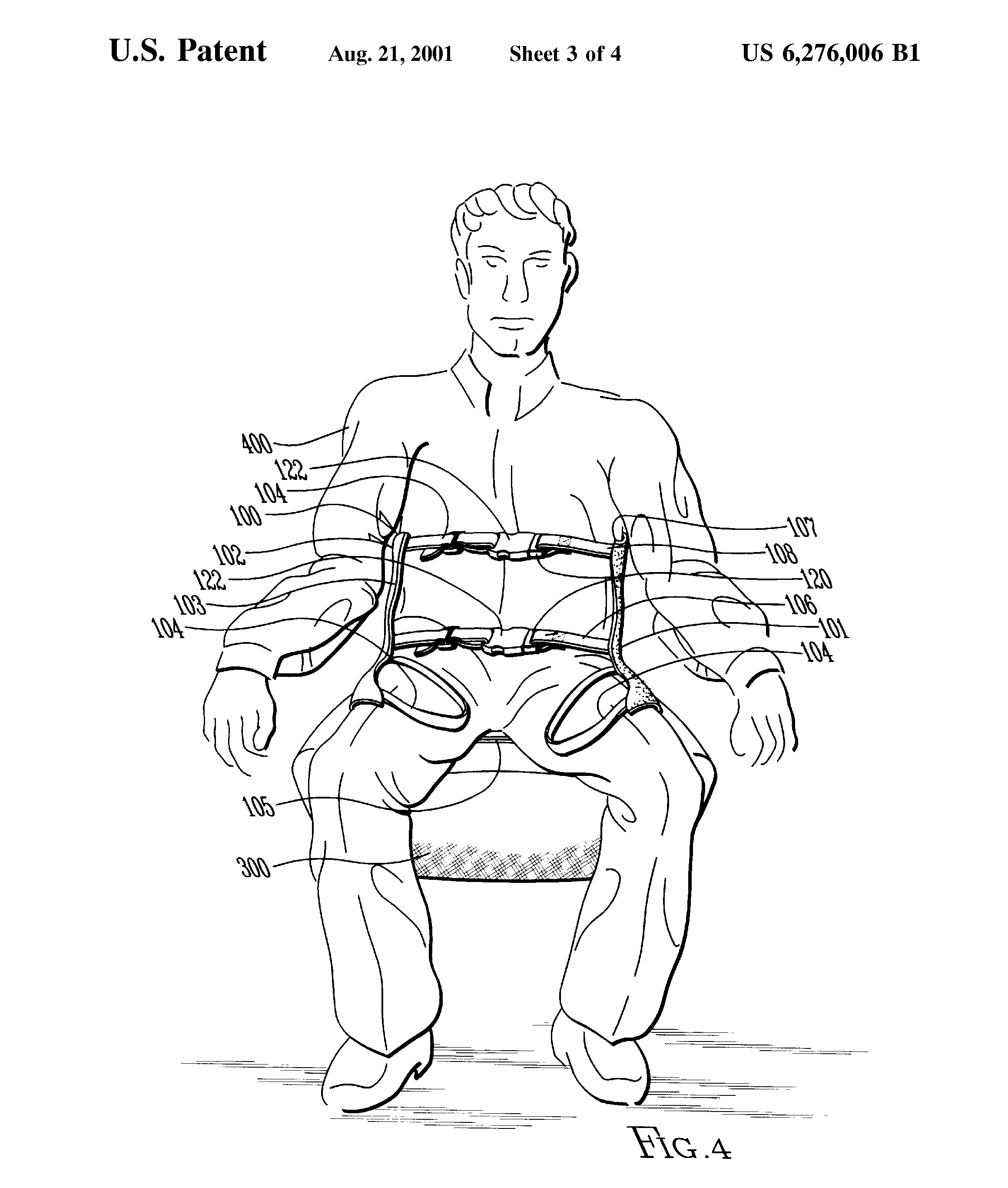

By design, onboard wheelchairs have multiple overlapping fastenings to protect the occupier during transit from their personally adapted wheelchair at the aircraft’s gate to their allocated seat. The thick webbing of fastenings crisscross the upper body like a straitjacket (especially constricting the arms), and another fastening binds the occupier’s legs to the onboard chair. The “trained” assistant, a term I use loosely here, maneuvers the chair back forty-five-degrees to roll the passenger into the aircraft. An awkward momentum gathers as four small, fixed wheels propel the chair backward—a slow dragging motion up the aisle and, for the majority, to the economy section of the aircraft. The restrictive functions of onboard chairs, a cross between a modern hospital gurney and a medieval ducking stool, are determined by regulations designed to limit the autonomy of disabled users for their own health and safety. Their lack of autonomy is further enhanced by the fact that the onboard chair’s small wheels are out of reach for the seated occupier.

In many ways, the chairs embody the antithesis of the independent living movement that inspired the disability rights movements in the United States and Western Europe. Their adoption of universal design principles and emphasis on interdependency and collective self-determination emerged in direct opposition to the extortion faced on an everyday basis by people flying or otherwise traveling while disabled: others’ access to the disabled body becomes the routine price paid for basic access to modern transportation in civil society.

“Everyday” and “routine” are no longer words applicable to the description of air travel. I began writing this essay shortly before the novel coronavirus entered “our common world,” to borrow a phrase from Judith Butler’s recent piece, “Human Traces on the Surfaces of the World.”8 In my own essay’s first, and now second, iterations, I presented the series of black-and-white illustrations of onboard wheelchairs to provide a visual for the aviation industry’s punitive approach to accessible travel. Not only are these glorified dollies painful for the occupant, but as the blueprint of its lifting contraption suggests, they are designed to minimize physical contact between airport assistance personnel and the wheelchair user, who is idealized in the technical blueprint as a manipulatable and genderless crash-test dummy. The lifting implement is designed primarily to avoid the negligent injury of the disabled flier, for which the airport personnel (and more importantly, the airport corporation) could be held liable. This is access technology, in other words, that shields access workers against the disabled body’s inherent liability.

On first glance, we might group the design of the onboard wheelchairs under the remit of accessibility, an object informed through some compromise between the spirit of disability activism and the letter of disability legislation. But this notion no longer has a realistic connection to disability justice. In practice, accessibility in air travel intensifies ableist violence.

Approaching this essay for a second time, the illustrations of the onboard wheelchairs also serve as artifacts for speculating on the shifting sphere of intimacies before and during a pandemic. Anxieties about transmission and a renewed uncertainty about sick and vulnerable bodies throws traveling with a disability into a new form of chaos. Our “new normal” will likely include a complex set of updated social interactions between disabled passengers and airport workers required to enact the new etiquette of social distancing.

The soiled swabs, invasive and intimate body searches, and close contact mediated by onboard wheelchairs before the global shutdown in world travel foreshadowed the mass contamination of world surfaces. “If we did not know before that we share the surfaces of the world, we do now.” Butler continues, “The surface that one person touches bears the trace of that person, hosts and transfers that trace, and affects the next person whose touch lands there.”9 For disabled and nondisabled passengers, touching unknown bodies has become an inevitable part of our collective flying experience. Ours is a common world held together by the precarious rise and fall of the aviation industry, where deviant bodies are forcefully entered into normative datasets and are probed as potential risks.

The coming convergence between airport security screening and disease surveillance foretells new horrors for disabled fliers. But as with its effect in every other dimension of society, changes to air travel in response to the pandemic will only accentuate existing inequalities. Will my very presence as an imagined vector of disease now pose a health threat to the flying public, justifying the ACAA exception to discrimination on the basis of disability? How will the non-caring proximities and forced intimacies of the airport experience be adjusted—if they remain viable at all—in an era of mandatory physical distancing? Air travel for disabled people was unimaginable before. It will be unimaginable again.

An early version of this text was first presented in San Diego, California, as part of the “NOW That’s What I Call Poetry” reading series, co-curated by Tina Hyland, Yesenia Padilla, and Grant Leuning.

-

The full text of the ADA, including changes made by the ADA Amendments Act of 2008, can be found here: link. ↩

-

The Air Carrier Access Act of 1986 is codified as part of US federal regulations. See Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Disability in Air Travel, Code of Federal Regulations, Title 14, Chapter II, Subchapter D, Part 382, link. ↩

-

I offer this term to resonate with social anthropologist Marc Augé’s work on “non-places.” In his 1992 study of this phenomenon, which predates 9/11, Augé describes transient spaces such as airports and freeways as culturally insignificant non-places that plunge modern individuals into a generalized anonymity. Passengers’ identities are linked only with their jurisdictional documents: passports, visas, and so forth. “The space of non-place,” he writes, “creates neither singular identity nor relations, only solitude and similitude.” See Marc Augé, Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity, trans. John Howe (1995; New York: Verso, 2008). ↩

-

Sasha Costanza-Chock, Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020). For further reading on the politics of technological or non-human entities, see Langdon Winner, “Do Artifacts Have Politics?” Daedalus, vol. 109, no. 1 (Winter 1980). ↩

-

Mia Mingus, “Forced Intimacy: An Ableist Norm,” Leaving Evidence, August 6, 2017, link. ↩

-

Mingus defines access intimacy as “that elusive, hard to describe feeling when someone else ‘gets’ your access needs. The kind of eerie comfort that your disabled self feels with someone on a purely access level.” See Mia Mingus, “Access Intimacy: The Missing Link,” Leaving Evidence, May 5, 2011, link. ↩

-

The full text for this regulation can be found here: link. ↩

-

Judith Butler, “Human Traces on the Surfaces of the World,” ConTactos, April 12, 2020, link. ↩

-

Butler, “Human Traces.” ↩

Louise Hickman is a senior research officer at the Department of Media and Communications at the London School of Economics and the Ada Lovelace Institute’s JUST-AI Network on Data and AI Ethics. Her research draws on critical disability studies, feminist labor studies, and science and technology studies to examine the historical conditions of access work. Louise is a member of the Critical Design Lab. She holds a PhD in communication from the University of California, San Diego, and is currently working on a book manuscript tentatively titled “The Automation of Access.”