A commodity is, in the first place, an object outside us, a thing that by its properties satisfies human wants of some sort or another. The nature of such wants, whether, for instance, they spring from the stomach or from fancy, makes no difference. Neither are we concerned to know how the object satisfies these wants, whether directly as a means of subsistence, or indirectly as a means of production.1

— Karl Marx, Das Kapital

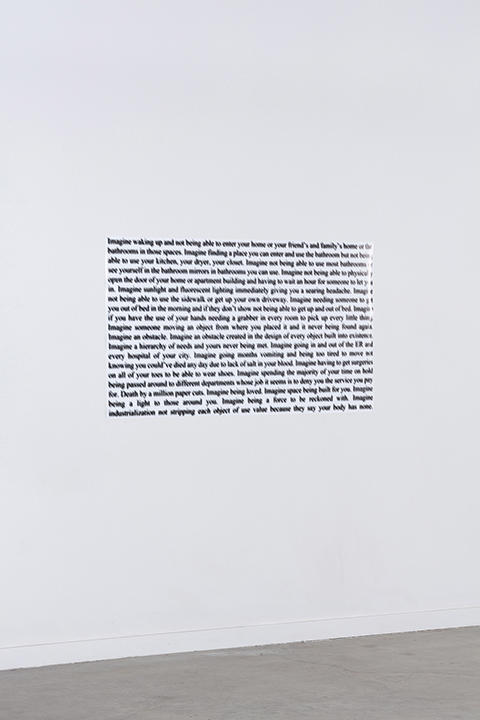

In their debut solo exhibition Built to Scale at Murmurs in the formerly wayward but now gentrified Los Angeles Arts District, artist Emily Barker illustrates how mass production disproportionately affects people with disabilities. The works on view are distributed across the gallery’s two-room exhibition space, with Untitled (Kitchen), the largest work included in the show, set in its center. Flanking Untitled (Kitchen), the works in the main room—Untitled (Ramp), Untitled (Grabber), Untitled (Rug), Out of Reach, Hierarchy of Needs, and At My Limit—reference architectural devices and objects that typically promote or inhibit accessibility whereas the works in the smaller foyer, Death by 7865 Paper Cuts and Untitled (Austerity), commemorate Barker’s own experiences navigating the bureaucratic brutality of the health care system to receive medical treatment.

While Built to Scale thematically highlights the design standards that have transformed mass-produced commodities—closet racks, dumbbells, posters—into ubiquitous home fixtures, the exhibition also presents a series of alternative accessibility aids and household furnishings Barker has conceived from materials that contradict their assigned use. Untitled (Rug), for example, is a rug comprising medical-grade plastic tubing and copper wire with detritus flourishes. It does not appear comfortable to sit or stand on; like many rugs, it would impede mobile wheelchair users. Untitled (Austerity), on the other hand, is a recording that loops between distorted call-waiting music, feedback, and a phone operator’s voice—the soundtrack of medical insurance purgatory. The “untitled” naming convention references conceptual artists such as Felix Gonzalez-Torres, who similarly used parentheticals to invite viewers to further extrapolate meaning from his work while also denoting that such works belong to an indeterminate set or series. The didactic tenor of this convention, which explicitly announces an assigned use, points to the schisms between bodies, languages, interfaces, tools, and built environments that recur throughout the exhibition—schisms in which assigned use is consistently thwarted.

Fundamental to this exercise of anticipated dysfunction is a structural critique of mass production protocols, which reproduce the same good at the same scale in marketplaces all over the globe. First identifying these household commodities as designed, sellable goods, then altering their physical properties, Built to Scale interrogates the incongruent relationship between design concepts and the lived experiences they hope to accommodate. By emphasizing disabled consumers—who, as the exhibition shows, pay additional psychological costs to use and access these goods—Built to Scale also traces the financial and psychic debts those with disabilities are forced to assume in built environments that frequently ignore their existence.

As Barker acknowledges in the press release for the show, design standards reinforce prejudice because they assume objects, people, and protocols share a universal basis that guarantees their interchangeability—an interchangeability that is structured by and productive of ableist, patriarchal, and white supremist ideology.2 This premise stems from a long history of design practices—stretching from Vitruvius, Leonardo da Vinci, and Leon Battista Alberti to Le Corbusier and many others across the twentieth century—that have developed the idea that a singular human form could provide the ideal subject for design.3 But Barker’s critique also echoes Marx’s formulation that commodities, labor, and value assume an abstract, proportional relationship over time:

In proportion as exchange bursts its local bonds, and the value of commodities more and more expands into an embodiment of human labor in abstract, in the same proportion the character of money attaches itself to commodities that are by nature fitted to perform the social function of the universal equivalent.4

In other words, the more abstract our relation to labor, the more abstract our relation to commodities that act as the universalizing agent in a given exchange (e.g., currency) proportionally.5 But, as Built to Scale demonstrates, once our relationship to human bodies and their limits becomes divorced from reality, our relationship to labor and commodities is sure to follow.

Mass production reduces labor to a mechanical process and its omnipresence makes for a world in which the handmade and custom-tailored are exceptions to any constructed norm—a scenario that was not the case during the Industrial Revolution, when Marx wrote Das Kapital. And because mass production ensures that goods are affordable, easy to use, and recognizable on an increasingly global scale—that is, they create a financial incentive to further standardize our lived experience—mass-produced objects likewise erase the specific environmental conditions that govern, for instance, how a person moves about their individual home in their individual body, relegating disabled bodies in particular to an afterthought. When Barker claims, “people do not yet realize that being ‘able bodied’ is a temporary privilege,” the artist intimates an aesthetic paradigm informed by foresight and lays bare the already debilitating bureaucracy and infrastructure that people with disabilities must anticipate if they are to survive under consumer capitalism.6

Thwarted Use, Thwarted Value

Indicating that physical scale and social value are corollaries, Barker has built prototypes such as Untitled (Kitchen) and Out of Reach that forecast the relationship between common domestic amenities and the bodies such amenities disable. Devised to thwart use—and thereby marking them as impaired commodities—Barker’s installations introduce a range of experiences and feelings that the disabled may encounter on a daily basis, reproducing these objects at a scale where their structural disadvantages cannot be denied. For example, at a distance, Untitled (Kitchen) appears to be a standard but also see-through model kitchen with an overhead cupboard and detached island. Moving closer reveals that its thermoformed plastic components, collectively held together by dime-size bolts, have been enlarged beyond practical use. It is a mammoth replica that, following Barker’s specifications, would be unusable for all bodies. Likewise, Death by 7865 Paper Cuts, a two-foot-tall stack of documents in the gallery’s antechamber, transforms Barker’s estimated $600,000 in medical bills into a readymade sculpture, while Untitled (Ramp) tucks the artist’s broken wheelchair underneath an accessibility ramp with a nearly vertical incline—a memento to the expensive mobility aid Barker had to fundraise to replace because their insurance did not cover it. In each case, these works anticipate their own thwarted use.

Mirroring the conspicuous argumentative style deployed in the press release, Barker lends these works a physically or rhetorically transparent structure—one that materializes the economic concerns disabled artists face when satisfying the contradictory demands of the private art market and public art institutions. If the private market offers opaque, untraceable transactions while public institutions proclaim transparency, Barker turns Untitled (Kitchen)’s transparent surface into a rhetorical conceit. The economic models and the modalities they reflect (such as opacity versus transparency) are far from being diametrically opposed; rather, they are shown to be different segments of the same economic transaction. The viewer’s relationship to the installation, its scale, and the market exchange the gallery context presupposes change in accordance with the viewer's distance from the work. As such, viewers are required to make a rhetorical—and to some degree empathetic—leap to understand the scope and magnitude of the critique Barker puts forth concerning disability and mass production in the exhibition.

Impaired Economies

Like most contemporary exhibitions, Built to Scale seeks to foment market exchanges: the works included in the show are ultimately for sale. Though an often-ignored aspect of exhibiting artwork, market sales and the information associated with these transactions—such as serial numbers, print edition, and provenance—have increasingly been incorporated into exhibitions, individual works, and ongoing projects as a way to reconcile artistic production with racialized property relations. If artists such as Michael Krebber and R. H. Quaytman have invoked their gallery’s inventory system to reveal, as David Joselit suggests, their coordinates within a larger economic network, other artists such as Cameron Rowland have pursued practices like drafting rental contracts that temporarily place works with collectors or exhibiting institutions, thereby obstructing the usual material and symbolic transaction a successful sale inaugurates and exposing contemporary legal infrastructure that has its origins in chattel slavery.7

There remain fertile grounds for aesthetic and economic critiques that focus on derailing an artwork from its status as an alienable, tradable commodity—especially for disabled artists like Barker who depend on government disability benefits and must therefore also contend with the terms and conditions under which they receive support. To qualify for Social Security benefits like Disability Insurance, for instance, one “must be unable to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of a medically determinable physical or mental impairment” (emphasis mine).8 In other words, applicants must satisfy a particular federal definition of disability as a relationship to work—not an embodied or somatic condition, not a relationship to one’s environment, not even the well-being one derives from labor, but the dollar amount one derives from their work. Forcing unlike disabilities into a common value—gainful activity—and then assigning monetary value to it, Social Security protocols obliquely locate an abstract, proportional relationship between labor and impairment that does not exist outside its calculus. Such a definition of disability, which Built to Scale hyperbolizes using physical proportion, imposes a monetary limit that, if surpassed, financially cripples those with disabilities beyond their already precarious state while labeling them adequately abled. (Please note the symbolic injury produced in this attack.) Taken from this vantage, federal law assumes the labor hours of abled and disabled people are equally convertible into wages and constitute one mass-produced good, as if being disabled did not affect one’s ability to conduct work and maintain a job—in effect producing a dehumanizing universal metric.

The federal SGA limit begins at $1,260 for the non-blind, so in Los Angeles, where the average rent is $2,527, disabled workers (including artists) without consistent, guaranteed income, must avoid appearing too independent, too self-reliant, too competent—lest they risk losing benefits—all the while living at or below the poverty line.9 To maintain their disability eligibility while selling the works included in Built to Scale, Barker would have to price them at a fraction of the standard market value for a debut exhibition, which would devalue the work and potentially jeopardize their benefits during the interim period between exhibitions. Or Barker would have to price the works outside the traditional price range associated with debut and emerging artists, which decreases the odds that a sale would occur; but, if successful, a sale at this proportion would give them enough capital to be able to afford their caretaker and recurring medical expenses, costs that their Social Security benefits currently absorb. This is perhaps the unseemly underside of the “forced perspective”—a standpoint the viewer is coerced into occupying—Barker glosses in the press release: to make a living as a disabled artist, they must constantly anticipate future obstacles, including market conditions, that immobilize them or jeopardize their well-being while, too, developing marketable aesthetic responses.

To this end, Built to Scale emphasizes the contradictions that arise even when an artwork’s symbolic value and assigned use supposedly coincide and forges connections between the abstract and material prejudices common to architectural practice. The “untitled” naming convention thus also pairs strings of codified information with their corollary units, formalizing a recurring syntax in the process. To the interchangeable variable “untitled,” whose precise function is to remain temporarily undetermined but forever anticipating its object, Built to Scale assigns values such as “rug,” “ramp,” and “kitchen,” which index the commodities the individual works replicate. But like any system, this formulation is always abstract, and the ways in which such abstractions affect marginalized groups is what is at stake in the exhibition. Namely, if material structures already impede the disabled, then the abstractions derived from these structures present yet another multiplying series of impasses and embargos that obstruct their movement through physical and social space. The remaining works in Built to Scale, with their explicit titles, indicate that this barrier is out of reach, occurring beyond a limit, leaving tiny, nearly invisible scars—such scars perhaps being the sites where surplus value has been forcibly extracted from the artist.

While Built to Scale is a collection of alienable, saleable commodities, it does not substantiate its collective value from the liquid assets it would be traded for. Rather this value emerges from the political critique it fastens to an exhibition space. In indexing these anatomical and economic proportioning tools that establish abstract, overarching formulae to the express disadvantage of disabled people, Built to Scale also reveals how symbolic values influence price and market worth, which bear upon the individual bodies to which they are assigned. Because, as the most common economic clichés in the art world demonstrate, artists themselves often perform as commodities who beget other commodities—and this is why Barker’s proportional, multiplicative approach must be understood with recourse to Marx.

Writing in the 1800s at the dawn of industrial capitalism, Marx had little means to understand automation, mass production, or their subsequent effects. Yet he theorized the consequences of an economic system in which commodities took on larger and larger values in comparison to the laborers who made them—foreseeing that capitalism would ultimately congeal the disenfranchised classes into an undifferentiated, glue-like animal substance, as theorist Keston Sutherland emphasized not so long ago in his 2011 book Stupefaction: A Radical Anatomy of Phantoms.10 Likewise, Marx does not extensively attend to the individuals who will be excluded from consumer capitalism because their bodies have or will become an unofficial currency, as Rowland’s work suggests of American slaves, prisoners, and undocumented laborers—a critique that I would likewise apply to legally vulnerable disabled individuals, who frequently must compromise or surrender their legal rights to receive medical care. But the exchange system Marx elaborates does clarify how commodities receive and stabilize their value using a currency substrate, such as gold or printed money. Built to Scale updates the list of possible entities that can function as such a substrate to include disabled artists, who can represent and prefigure the monetization of abstract value. As Marx writes:

Objects that in themselves are not commodities, such as conscience, honor, etc., are capable of being offered for sale by their holders, and of thus acquiring, through their price, the form of commodities. Hence an object may have a price without having a value. The price in that case is imaginary, like certain quantities in mathematics. On the other hand, the imaginary price-form may sometimes conceal either a direct or indirect real value-relation; for instance, the price of uncultivated land, which is without value, because no human labor has been incorporated in it.11

In cases where the artist serves as both the laborer producing a work as well as the figurehead from which an artwork derives its economic and social value, it is strange for the work to remain under the jurisdiction of the artist. Historically, the sale would substantiate a contractual agreement that would initiate a transfer between the artist and collecting entity, whether an individual or institution, and that exchange in and of itself would constitute a social currency. Barker, by labeling themselves a disabled artist and producing work about disability, also creates symbolic currency for the gallery or the nonprofit exhibition space. In a milieu where artists are commodities, artists function as different types of currency while representing their value. But Barker anticipates this tokenization and embeds it into the conceptual apparatus of their work, thereby pinpointing the intersection where disability—as a symbolic currency—produces an aberration in the metric that correlates value and price. Notably, the ability to index value, price, and disability—a competency that interfacing with a bureaucratic healthcare system no doubt strengthens—also ruptures the myth that individuals with disabilities are strictly disabled and therefore incapable of doing anything. Meanwhile, Barker's ability intimates the asymptotic performance that individuals with disabilities must undergo if they are to be understood as disabled in one respect while entirely capable in another.12 And Built to Scale visualizes that performance in shape-shifting architectural and economic terms, insinuating that a latent economic deadlock resides within the exhibition's purview—a deadlock that the exhibition seeks to further explicate.

Barker’s works anticipate and embody this economic deadlock within their object-based propositions. Notably, At My Limit, which consists of a 3D-printed hand wrapping around a twenty-pound weight, uses materials that are purposely lackluster and didactic to annotate a compromised exchange: the hand and its mechanical arm will not and should not lift the weight, or else they will be damaged, much like Barker’s rotator cuff, which will bear the strain of their wheelchair use and deteriorate at an expedited rate. This painfully symbolic gesture is also predicated on the collector or exhibitor accepting aesthetic practices that contradict popular notions of the beautiful, the abstract, and the exquisite that propel corporate art sales in Los Angeles and abroad. In other words, to exhibit the works in Built to Scale is to make oneself vulnerable to critiques of tasteless politicizing—something that is implicitly suggested of disabled people when they ask for basic amenities to be made available to them.

Anticipating the Past

Built to Scale contends that the disabled are forced to work with faulty tools, with instruments that ironically cripple them further, under conditions like the Social Services protocols that guarantee they will remain in economic precarity. “We live in a world where labor is a commodity, health is a fantasy, and cures, often available only for the very wealthy, exist only to return a person to work,” Barker writes.13 Mass production, they argue, assumes a standard body able to use these alienable goods; mass-produced commodities rupture the “local bonds” Marx describes, which are first and foremost located in the individual body. In terms of sheer quantity, mass-produced goods—now a currency in their own right—outnumber disabled people and have more logistical support than will ever be available to any disabled person or population so long as consumer capitalism reigns. Without a sizable intervention—an intervention built, as the exhibition’s title implies, to the scale of the problem—the disabled will continue to be treated as if their unique bodies should accommodate one-size-fits-all manufacturing, and not the other way around.

If disability is an aesthetic paradigm, then it is also inseparable from the market and political conditions in which it is situated. While artists with disabilities face similar forms of impairment, the works they create will also respond to the particular conditions of their environment, even and especially if those conditions only affect the disabled. If Barker can be said to make commodities that resemble or constitute impairment, such commodities would indicate where a market could foment under different conditions—if health care were subsidized, for example, or if accessibility aids were legally required to be state-of-the-art. But we don’t live in that world, and Barker’s artworks index the social norms that guarantee its foreclosure. Impairment in this case prima facie isolates where an object must disrupt the flow of exchanges, must require an unprecedented transaction. This is precisely what makes Barker’s solo debut so authoritative: it demands an entirely new set of socioeconomic relations in which disability, because it is inevitable, must be the first concern.

-

Karl Marx, Das Kapital, a Critique of Political Economy, ed. Friedrich Engels, condensed by Serge L. Levitsky (Chicago: Gateway, 1956), 1. ↩

-

Disability theorists such as Jos Boys, Aimi Hamraie, Tobin Siebers, Judith Butler, Tanya Titchkosky, and Rod Michalko have written extensively on “interchangeability.” When applied to architectural space, interchangeability often assumes that all bodies function and are perceived in the same way, which not only blocks some individuals from occupying an exclusive space but also renders the impediment or barricade that excludes them invisible. In “Designing Collective Access,” anthologized in Jos Boys’ Disability, Space, Architecture, Hamraie suggests this “spatial segregation…actively conditions and shapes the assumptions that the designers, architects, and planners of these value-laden contexts hold with respect to who will (and should) inhabit the world.” In other words, architecture has the ability to make people invisible and therefore less valuable to society at large. Aimi Hamraie, “Designing Collective Access,” in Disability, Space, Architecture: A Reader, ed. Jos Boys (New York: Routledge, 2017), 78–79. ↩

-

Le Corbusier conceived his Modulor, an anthropomorphic visual scale, in the aftermath of World War II—again tying mass production to profound technological shifts that reshaped our societies and environments. The Modular was an attempt to produce a mathematically consistent and thus abstract relationship between human physiology and built environments. Using the golden ratio, which similarly conjoins geometric and organic patterns, like Vitruvius, Leonardo da Vinci, and Leon Battista Alberti before him, Le Corbusier originally sought a standard model that could predict how much living space individual occupants of a room or building would need that also allowed him to circumnavigate the difference between the metric (British) and imperial (American) measurement systems. It should be noted, too, that several measuring systems derive their name and units from human limbs or their gendered, anthropomorphic proportions. A foot, for example, is supposed to span the size of a male human foot and a cubit refers to the average length of a male human forearm. ↩

-

Marx, Das Kapital, 69. ↩

-

I emphasize proportionality here because it is crucial to understand the double layer of abstraction that Marx criticizes. Because time itself is already abstract, any corollary that uses time also multiplies that abstraction. While Marx’s many critics, such as economist Mark Spitznagel and art critic Isabelle Graw, argue that he overestimated labor as the force that determines value, it is important to remember that Marx is evaluating labor as a performance—specifically a performance that crystallizes value later to be absorbed by the upper social classes, who derive their wealth from the dividends labor produces. So, in Marx’s view, the laborer earns a profit based on a direct number of goods sold or services rendered, whereas the bourgeois capitalist profits from the transactional costs associated with these exchanges, which Marx calls surplus value. By the time a bourgeois profiteer is able to accumulate surplus value, the relationship between time, labor, commodity, and value is so thoroughly abstracted that neither the individual who produced the commodity nor the environment in which it was made retain their visibility. The variable that produced them, labor, has since been excommunicated from the equation. Marx spends most of Das Kapital reminding us that this originary loss occurs in each case where laborers produce value for their employer. ↩

-

All quotes from Barker are sourced from the Built to Scale press release. See “Emily Barker: Built to Scale,” Murmurs, December 14, 2019–January 18, 2020, press release, link. ↩

-

Joselit’s writing about networked paintings can be found in “Painting Beside Itself,” October 130 (Spring 2009): 125–134. For more information about artist contracts, Rowland, and his rented works, please see Eric Golo Stone, “Legal Implications: Cameron Rowland’s Rental Contract,” October 164 (Spring 2018): 89–112. ↩

-

Social Security Administration, Disability Insurance, “SSR 82-52 Titles II and XVI: Duration of the Impairment,” link. ↩

-

Social Security Administration, “Substantial Gainful Activity: Amounts for 2020,” link. See also Jack Flemming, “LA Rent Rose 65 Percent over the Last Decade, Study Shows,” Los Angeles Times, December 27, 2019, link. ↩

-

Keston Sutherland, Stupefaction: A Radical Anatomy of Phantoms (London and New York: Seagull Books, 2011). ↩

-

Marx, Das Kapital, 81. ↩

-

For more information about this asymptotic relationship between disability and competency, please see this excerpt from my essay, Adequate Screens, published by Open Space (SFMOMA), link. ↩

Evan Kleekamp lives and works in Los Angeles, where they founded NOR Research Studio. In 2019, they were a finalist for the Creative Capital | The Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant.