Pushki oats make a small pile in the palm of my hand. Pushki plants are from the carrot family and also go by the name Indian celery or cow parsnip, among other hailings. I wish that I knew the word in dAXunhyuuga’ for pushki.1 I’m certain that, like today, we used it then, a time when we knew all of our words. Under “Native American Uses” in a plant identification book—typically stripped of the origins of botanical knowledges—one can learn that young pushki shoots are peeled and eaten raw. The roots can be cooked and eaten too, prepared like any other root vegetable. Both nutritional and medicinal, roots can be ground and made into a paste to ease aching joints.

I pinch several oats between my fingers, crumble the small seeds and bring the plant matter to my nose. I inhale the scent of summer river water, quick and deep, banking left and right, gray-blue with glacier silt. I inhale memory, picking salmonberries on a steep incline as a kid. Fat, dimpled berries plopping heavy into an empty ice cream bucket, two bikes ditched on the road below. Reaching high for that ever-next orange berry, stretching across pushki patches, I can feel their green hairs tickle and scratch. Later, pink and red rashes would rise on my irritated arms and legs as I drowned my berries in milk and sugar, eating them whole, little green bugs and all. Now, I rub the crushed oats between my fingertips, sprinkling them onto the small lawn behind my apartment where I live in Ho-Chunk country. I’m late introducing myself. I offer dried pushki seeds from home as a simultaneous hello, I’m sorry, and thank you. I am a stranger here, and I hope that my tardiness is forgiven.

Pushki can cause rashes when it and human skin touch and mix with sunlight, but it has an even more dangerous familiar: water hemlock. I appreciate this dark and mischievous feature of plant life. Two plants that could pass for sisters, one a gift for the human body and the other most fatal. The US Department of Agriculture, in true dramatic flair, writes that “water hemlock is the most violently toxic plant that grows in North America.”2 Another plant often misidentified as pushki and water hemlock is Queen Anne’s lace. To me, a plant by this name, frilly with empire, sounds by far the most lethal. All three plants grow tall stalks topped by upside-down umbrellas of white flowers that face the sky. By the end of summer, remaining pushki seeds dry in the sun on the top of their stalks and can be plucked.

My urban gift of pushki oats is a start, an offering to build a new relation in a good way. This season I won’t greet the pushki back home because this will be the first summer that I won’t be making the annual migration. My family sends me images of fish heads, fish eggs, fish fillets cut clean from their vertebrae, fish head broth clear and richly clouded with fish oil, fish backs on cookie sheets hot out of the oven. Bright harvests of tightly furled fiddlehead ferns and speckled seagull eggs. Fireweed shoots dark pinky-purple and spruce tips verdant green. My nephew tastes his first bite of smoked king salmon cheek over the screen of my phone. Hummingbirds and shorebirds make their migration destination known, flitting by windows in search of sugar water in plastic feeders and in murmurations on muddy banks.

The city of Cordova is a young thing—just over one hundred years old, established in 1909. The town is built atop village sites, walking and hunting trails, burial grounds, and fishing and harvesting spots named and utilized by dAXunhyuu for centuries. Over decades of settler occupation, many relationships with fish have transformed and been commoditized into a commercial fishing economy. Since the 1940s, commercial fishing has been the main source of income for the community of now about 2,300 people. However, each summer this number spikes when hundreds of seasonal workers travel to Cordova to constitute a major part of the commercial fishing workforce and its connected economies. Some fishermen live in Cordova, but others travel in from their permanent homes elsewhere to use their limited-entry fishing permits and fishing vessels. Others travel to take jobs as contracted crew members on fishing boats that gillnet, seine, or tender. Others come to work at one of five seafood processing plants in town. Seasonal sub-economies grow in relation: workers build and mend fishing nets, serve food and drink, or guide the tourists who come to visit the small town built upon dispossession just underfoot.

While on the surface Cordova appears to be tucked into a rural cranny along the sparsely populated Alaskan coastline, this sheltered cove is actually routed through with circuits of labor and capital. The commercial fishing economy staged here is a local, national, and global industry, with fish made into goods that are shipped out by the tons and laborers coming in by the hundreds. This wide network of traffic seems unlikely when walking down the town’s modest Main Street, which houses the bulk of its businesses. Yet tentacles of capital have already wound through and around Cordova and nearby lands multiple times over in the form of a failed railroad, a boom-and-busted clamming economy, and multiple failed oil and gas explorations. Along with these entrenched routes of circulation have come the transmission of disease and violence, the conditions of colonial-capitalism rendering some most vulnerable and disposable. Our current moment of social unrest lays bare these connections between capitalism and racialized violence. And while this slow, sleepy town of Cordova may seem geographically separate, a spatialized rurality should not be considered socially or politically “beyond” or “outside.” In a quite literal sense, the salmon of my people corporally constitute the fish-eating individuals of this country, and in turn my community is shaped and constituted by bureaucratic decisions made about said fish. This historical relationship, forged in colonialism and empire, is even more intimately felt in the current moment of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The power dynamics of many other historical relationships are also brought into view by this pandemic, dynamics that are similarly coupled with fish relationships in coastal Alaska. The pandemic is gravely felt and experienced by many others around the world, especially in the US, and particularly by Black, Indigenous, and communities of color.3 Even before the recent shift in public thought, it was already clear that Black people in the US are killed by structural, systemic racism that has undergirded and supported American society from slavery onward. This has become further obvious in a current moment when Black Lives Matter uprisings across the US revolt against unchecked policing and state-sanctioned murder of Black people in their homes, in parks, on sidewalks, jogging in their neighborhoods, or in police custody, such as Breonna Taylor, Tamir Rice, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Sandra Bland, among many others who often go publicly unacknowledged. As researchers continue to collect and cohere coronavirus data, they find that such systemic and lethal racist conditions in the US exacerbate the COVID-19 pandemic in Black communities.4

Many other multi-sited, pre-existing injustices are emerging to a dominant viewing public. For instance, the federal government’s one-time $1,200 stimulus checks were denied to undocumented individuals and mixed-status families by the administration, and state governments did not step in to fill that gap.5 Moreover, members of mixed-status families often hold positions that have been deemed “essential” and are therefore disproportionately exposed to greater risks of COVID-19.6 For Native communities and for Native people, rates of the virus have also been disproportionate. This is especially true for the Navajo Nation, which has the highest per-capita infection rate in the country, surpassing both New York and New Jersey.7

The rapid mobilization of militarized police and National Guard across the US, which essentially happened overnight, makes the government’s shamefully sluggish response to the public health crisis appear particularly bleak.8 The US has seen the greatest number of COVID-19 deaths in the world.9 Yet the federal administration has not committed to making COVID-19 testing widely available, nor insisted on contact tracing to mitigate further transmission even as states reopen. Instead, the president has actively encouraged citizens to revolt against state-mandated shelter-in-place orders,10—to ingest disinfectants as possible cure,11 and to take potentially deadly medicines that have not been proven to combat the virus.12 Meanwhile, hospital professionals lack necessary personal protective equipment (PPE).13 During this pandemic, the rich have gotten richer14 and corporations have received billion-dollar bailouts15 while more people are currently filing for unemployment than have ever before.16 Workers continue to organize strikes17 and make demands for better working conditions.18 Especially noteworthy are those who organize their efforts within companies like Amazon and its subsidiary Whole Foods Market, where CEO Jeff Bezos is now well on his way to becoming the world’s first trillionaire.19 Unfortunately, rather than demonstrate solidarity with workers and activists who creatively imagine better futures, mainstream media has been more interested in covering “reopening” demonstrations-cum-Trump rallies replete with dozens of men outfitted in makeshift riot gear and assault rifles—likely the same individuals who went on to constitute vigilante militias countering Black Lives Matter demonstrations.

Along Alaska’s coastline and throughout rural spaces of the state, unique scenarios have given rise to particular responses. Many communities in rural Alaska are severely and historically under-resourced,20 have inadequate or nonexistent medical infrastructure, and lack running water.21 Uncoincidentally, Native communities make up most of rural Alaska’s underserved population and public health experts have named Alaska Natives as one of the most “at risk” populations in the US, which “may put them at higher risk for serious illness if they contract coronavirus.”22 Yet, widespread health conditions are not accidental or merely a result of unwise “lifestyle choices.” Ongoing coloniality and rampant under-resourcing of Native communities across the US remains the main driver and indicator of Native health.23 Moreover, when the federal government does attempt to meet health care needs in Native communities, ineptitude persists: for instance, the CARES Act passed on March 27 as part of federal COVID-19 relief, earmarking $4.8 billion in pandemic funds for use by tribal governments. However, those funds were held back from distribution for nearly two months, and it was only on June 17 that a federal judge ordered the release of the full stimulus funding.24 This stall is likely unsurprising to many Native communities who have long experienced paternalism, administrative neglect, and explicit violence at the hands of the federal government.25 For example, when the Seattle Indian Health Board requested COVID-19 supplies, they were instead sent body bags.26 Anticipating neglect, many tribal entities, like the Lummi Nation, began preparing for COVID-19 before the US responded to its danger; Dakotah Lane, M.D., (Lhaq’temish) stated that “we don’t want to count on help reaching us.”27 Other responses by Native communities include similar demonstrations of autonomous governance,28 and the bolstering of community wellness and collective memory29 by following previously established pandemic protocols.

One such protocol is the exercise of sovereignty over territory. Tribal governments demonstrate repeatedly that they do not wish to be a conduit for unwelcome guests in the many forms that they may take. In Alaska, tribal governments and local leadership prohibited unnecessary travel to their medically underresourced communities, using rurality and relative isolation to their benefit.30 Local travel limitations are consistent with other tribal governments’ decisions to considerably slow if not halt incoming traffic to reservations31 and First Nations reserves.32 Apart from those seeking privileged refuge in country cottages and vacation home getaways33—as well as ignorant travelers looking to escape the city, who are sent back whence they came34—it has so far been possible to halt major influxes of travelers into Indian Country.35 Such enactments of sovereignty are not new or anomalous for Native governments. Sovereignty is practiced daily, often in mundane forms and therefore goes largely unnoticed.36 However, when enactments of tribal autonomy come into direct conflict with the settler state’s, that sovereignty comes into question. This is especially true when assertions of sovereignty are in conflict with resource extraction by settler powers.37

For instance, in places like Cordova and coastal communities further to the west in Bristol Bay where Native lands are now also staging grounds for multimillion-dollar commercial fishing economies, exercising sovereignty over territory disturbs market desires. Here, that eighty-year-old industry acts as colonial infrastructure wherein market interests ensure the flow of fish capital out to state, nation, and globe. Native lands are thus rendered “connected” via routes of capital that take resources out and bring infrastructure in. This connection creates a scalar rurality in that other “resource-poor” villages of Alaska are not subjected to this extractive exchange but instead experience substantial forms of governmental neglect. Moreover, the first salmon runs of the year happen near Cordova, meaning seasonal workers arrive here earliest. This is why journalists have referred to the town as “a testing ground” for how seafood processors and the local city council would mitigate the risk of COVID-19 potentially brought into the community by a traveling workforce.38

With the impending influx of hundreds of seasonal workers, community members in both Cordova and the Bristol Bay region raised legitimate concerns about the spread of COVID-19 to their communities. Cordova residents started a petition urging the mayor and city council to block seasonal workers this year.39 The Native Village of Eyak Tribal Council of Cordova passed their own resolution to limit travel into town except for critical needs.40 Local governments in Dillingham, a community in the Bristol Bay area, requested that the governor of Alaska close the Bristol Bay commercial salmon fishery for the 2020 season.41 Led by Native governments, tribal councils and city councils across Alaska exercised their sovereignties and made demands to the state to keep their small communities safe from COVID-19 harms.42 Tribal governments cited and recalled the 1918 flu epidemic, wherein many lives were lost,43 including the majority of many Native communities,44 due to the transmission of a similarly deadly disease.45 Executive director of United Tribes of Bristol Bay Allanah Hurley (Yup’ik) stated, “Our people keep saying we went through this already. A lot of us are descendants. So, for Native people, the devastation of a pandemic is not an obscure concept. We are the people raised by the orphans who survived.”46 Likewise, in regard to COVID-19 responses in the contiguous US, Desi Rodriguez-Lonebear (Cheyenne) stated, “more than any other population in the country, the shared experience of surviving a pandemic is in our blood, it’s not historic, it’s current for American Indians, it’s our reality.”47 dAXunhyuu have also felt our own multiple waves of loss due to settler diseases, from the 1918 flu epidemic and before.

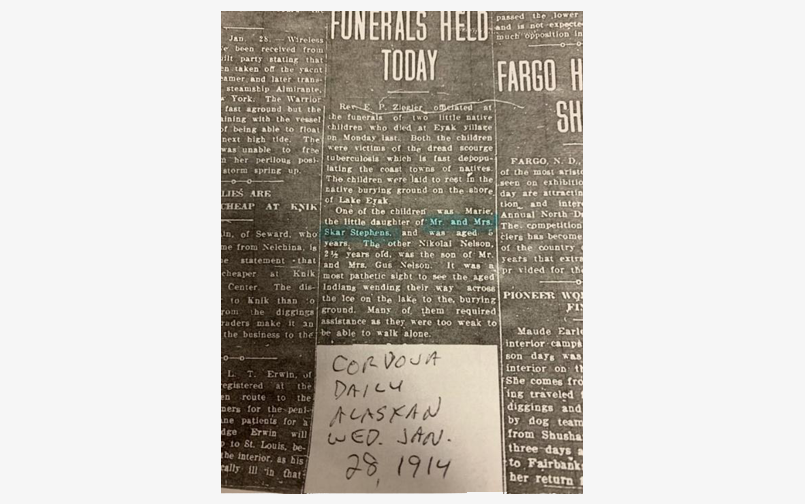

For instance, by 1914, dAXunhyuu of the Eyak Lake area had already been hit hard by tuberculosis. A newspaper clipping from January of that year reads, “Rev. E. P. Ziegler officiated at the funerals of two little native children who died at Eyak village Monday last. Both the children were victims of the dread scourge tuberculosis which is fast depopulating the coast towns of natives. The children were laid to rest in the native burying ground on the shore of Lake Eyak.”

Although many community members in Cordova and the Bristol Bay region worked to reimagine the 2020 fishing seasons hosted in their lands, Alaska state administration decided that both economies would continue but with strict regulations adopted by seafood processing companies. On May 6, Cordova announced its first confirmed COVID-19 case; the individual who tested positive had traveled there to work as an employee for Ocean Beauty Seafoods, a processing plant.48 On June 17, the second case was reported in Cordova involving another asymptomatic individual employed by the same company.49 The first confirmed COVID-19 case in Dillingham was also a person who had traveled to the region to work for a seafood processing plant.50 There have now been five cases of COVID-19 in the Bristol Bay region, four of which have been out-of-state workers involved with the fishing industry.51 As of June 4, twenty-six new cases were reported in Alaska, eighteen of them among nonresidents and all but one among seafood workers.52 In Whittier, Alaska, eleven people at a seafood plant tested positive for coronavirus, the first confirmed cases in a town of 280 residents, where almost every community member lives in the same condominium building.53 The working conditions of seafood processing plants have been compared to those of meat processing plants in the Lower Forty-Eight, where infections spread easily due to the often shoulder-to-shoulder factory lines and the need to shout over loud equipment.54 As part of their risk management plans mandated by the state,55 seafood processing companies require employees to take a COVID-19 test before traveling to Alaska and again once they arrive, after which they are required to quarantine for two weeks. To promote social distancing in seafood processing plants, companies require that workers not speak to one another (reinforcing this by staggering coffee and lunch breaks); that employees not interact with community members in the towns where they work; and that workers not exit the campus grounds, which are often no more than scattered clusters of temporary housing. As one article reports, “Ocean Beauty Seafoods put up a chain-link fence around its plant in Naknek. ‘It’s got a gate and a guard. And when workers come in they stay there until they go out on the 27th of July.’”56 These containment working conditions are lauded by many in the state as successful and even “fantastic.”57 On June 21, the Los Angeles Times reported that a lawsuit has been filed against North Pacific Seafoods by seasonal employees who have been forced to quarantine in a hotel near the LA airport for eleven days and counting, without pay, after three individuals tested positive for COVID-19 before they were due to travel to Naknek.58 The lawsuit “alleges false imprisonment, nonpayment of wages, failure to pay minimum wages and overtime, negligence and unlawful business practices,” as these individuals stranded in Los Angeles have been warned, “that if they left their rooms for any reason they’d be immediately fired.”59

This is not the first instance of questionable labor regulations utilized by seafood processing plants around Alaska. Many seafood processing companies have utilized the J-1 Summer Work Travel (SWT) visa program that is meant for “cultural exchange” for visitor and temporary workers. Companies in Alaska have typically employed five thousand guest workers each season wherein they labor sixteen-hour shifts, six days a week, and have been required to pay for their own travel and health insurance while employed. According to a 2016 report, by using the J-1 program, seafood companies pay at least $2.31 per hour less than the statewide average wage for fish cutters and trimmers.60 The J-1 visitor program has been investigated before61 and has been under State Department scrutiny since 2011.62 While seafood companies are working to strictly adhere to their COVID-19 risk management plans, the virus continues to spread among workers, and the working conditions are quite severe. Yet, such conditions are considered the best form of “safety,” so long as the virus doesn’t escape the confines of the campus where individuals employed by seafood companies live and work.

During a press briefing at the end of March, Alaska’s lead doctor for handling COVID-19 said, “We know the fish are coming regardless of COVID-19 or not and we can’t ask them to stay home.”63 With this sentiment, the commercial fishing economy and the circulation of commoditized goods are made inherently natural, just as much as anadromous salmon returning to waterways to procreate, spawn, eat, and thrive. If the fish won’t “stay home,” then neither can fishers or seasonal laborers—for fish were made to be caught, processed, and exported out of their homes, no matter the endangerment of human life. The architectures of empire and capital crystallize in the invented necessity of labor circulation, the movement of goods, and unfettered access to resources. Colonial infrastructures work to naturalize themselves as just another part of the landscape while aiming to supersede First Peoples and their sovereign governments. Yet, the imperative to force territories open has always had lethal consequences. Within hyper-mobile settler capitalism, resources exit and viruses enter; mobility and entrapment co-constitute the conditions of extraction and occupation.

Now that the Copper River salmon season is well underway, market prices for salmon are low—just one quarter of typical for this time of the year. Fishing periods have been limited due to a smaller-than-normal run, continuing a downward trajectory of years past in relation to a changing climate. While seasonal workers of the commercial fishing economy pour into small, medically ill-equipped communities across the state, some pooling in isolation behind processing campus fences, it remains to be seen if the migratory relation on which it’s all based will also show face. This summer, as I continue to offer pushki prayers to a land that does not yet know me, I do my own accounting of jars of smoked fish in the cupboard. I hope that those most at risk will be spared and I am moved to practice old and new forms of care for, as Dr. Dakotah Lane put it, we can’t count on help reaching us.

-

dAXunhyuuga’ means “words of the people” or words of dAXunhyuu. dAXunhyuu are more commonly called “Eyak” people, from the Sugst’un word “igyaaq” or “iiyaaG,” meaning “throat,” referring to the “throat of the lake” where Eyak Lake empties into the Eyak River, the location of one of the original traditional village sites of dAXunhyuu. The original homelands of dAXunhyuu span from what’s now considered Cordova down to Yakutat, along Alaska’s south-central to southeast coast. ↩

-

“COVID-19 in Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 18, 2020, link. ↩

-

Harmeet Kaur, “The coronavirus pandemic is hitting black and brown Americans especially hard on all fronts,” CNN, May 8, 2020, link. ↩

-

Almita Miranda, Zoom Presentation, “Latinx Mixed-Status Families and COVID-19: Perspectives and Responses,” Northwestern University, June 12, 2020. ↩

-

Maeve Higgins, “The Essential Workers America Treats As Disposable,” New York Review of Books, April 27, 2020, link. ↩

-

Kalen Goodluck, “COVID-19 Is Sweeping through the Navajo Nation,” Wired, May 23, 2020, link. ↩

-

Jake Lahut and David Choi, “Trump threatens ‘heavily armed’ military deployments to quash protests if governors and mayors do not ‘establish an overwhelming law-enforcement presence,’” Business Insider, June 1, 2020, link. ↩

-

Over a hundred thousand deaths and rising at the end of May. See “An Incalculable Loss,” New York Times, May 24, 2020, link. ↩

-

James Fallows, “2020 Time Capsule #15: ‘Liberate,’” the Atlantic, April 18, 2020, link. ↩

-

Katie Rogers, Christine Hauser, et al., “Trump’s Suggestion That Disinfectants Could Be Used to Treat Coronavirus Prompts Aggressive Pushback,” New York Times, April 24, 2020, link. ↩

-

“Trump drug hydroxychloroquine raises death risk in COVID patients, study says,” BBC News, May 22, 2020, link. ↩

-

Sophia Ankel, “Photos show how shortages are forcing doctors and nurses to improvise coronavirus PPE from snorkel masks, pool noodles, and trash bags,” Business Insider, April 23, 2020, link. ↩

-

Robert Frank, “American billionaires got $434 billion richer during the pandemic,” CNBC, May 21, 2020, link. ↩

-

Alan Rappeport and Niraj Chokshi, “Crippled Airline Industry to Get $25 Billion Bailout, Part of It as Loans,” New York Times, April 14, 2020, link. ↩

-

Don Lee, “Unemployment hits 14.7 percent in April. How long before 20.5 million lost jobs come back?” Los Angeles Times, May 8, 2020, link. ↩

-

Michael Sainato, “Retail workers at Amazon and Whole Foods coordinate sick-out to protest COVID-19 conditions,” the Guardian, May 1, 2020, link. ↩

-

Brent Schrotenboer, “Hundreds of McDonald’s workers plan Wednesday strike over COVID-19 protections,” USA Today, May 19, 2020, link. ↩

-

Brett Molina, “Jeff Bezos could become world’s first trillionaire, and many people aren’t happy about it,” USA Today, May 14, 2020, link. ↩

-

JoJo Phillips, “Profile: ‘Unserviced’ Communities Part 1—Why Five Bering Strait Villages Don’t Have Basic Sanitation,” KNOM, April 29, 2020, link. ↩

-

JoJo Phillips, “Ghosts of 1918 pandemic haunt Bering Straits villages as they face COVID-19 without water or sewer,” Alaska Public Media, May 7, 2020, link. ↩

-

Samantha Artiga and Kendal Orgera, “COVID-19 Presents Significant Risks for American Indian and Alaska Native People,” Kaiser Family Foundation, May 14, 2020, link. ↩

-

Yin Paradies, “Colonisation, racism, and indigenous health,” Journal of Population Research 33 (2016): 83–96. ↩

-

Rebecca Beitsch, “Judge orders Mnuchin to give Native American tribes full stimulus funding,” the Hill, June 17, 2020, link. ↩

-

Andrea Shalal, “US Treasury to distribute $4.8 billion in pandemic funds to tribal governments,” Reuters, May 5, 2020, link. ↩

-

Erik Ortiz, “Native American health center asked for COVID-19 supplies. It got body bags instead,” NBC News, May 5, 2020, link. ↩

-

Nina Lakhani, “Native American tribe takes trailblazing steps to fight COVID-19 outbreak,” the Guardian, March 18, 2020, link. ↩

-

Jessica Kolopenuk, “Indigenous Peoples Are Not Canada’s Charity Case,” Canadian Science Policy Centre, May 20, 2020, link. ↩

-

Brenda J. Child, “When Art Is Medicine,” New York Times, May 28, 2020, link. ↩

-

Alejandro de la Garza, “Alaska’s Remote Villages Are Cutting Themselves Off to Avoid Even ‘One Single Case’ of Coronavirus,” Time, March 31, 2020, link. ↩

-

Creede Newton, “COVID-19 could ‘wipe out’ tribal communities with at-risk populations, New Mexico Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham warns,” Al Jazeera, April 2, 2020, link. ↩

-

Anna Mehler Paperny and Kelsey Johnson, “Canada’s First Nations close borders over coronavirus, using ‘isolation as a strength,’” Microsoft News, March 20, 2020, link. ↩

-

Rick Westhead and Alexandra Mae Jones, “‘Please stay home’: Town locals across Canada urge tourists not to visit this long weekend,” CTV News, May 14, 2020, link. ↩

-

CBC News, “Quebec couple fleeing COVID-19 ‘endangered’ Yukon First Nation, chief says,” CBC News, March 30, 2020, link. ↩

-

Erik Ortiz, “Dispute over South Dakota tribal checkpoints escalates after Gov. Kristi Noem seeks federal help,” NBC News, May 21, 2020, link. ↩

-

This concept of Native sovereignty is inspired by chatting with Rebecca Nagle about her podcast This Land. ↩

-

For three current examples, see the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe holding their ground on COVID-19 checkpoints in South Dakota, the current Supreme Court case of Carpenter v. Murphy, or the Wet’suwet’en movement to protect their lands from pipeline construction. ↩

-

Mike Baker, “Thousands Are Headed to Alaska’s Fishing Towns. So Is the Virus,” New York Times, May 14, 2020, link. ↩

-

“Travel Restrictions Petition to Mayor Clay Koplin and the City of Cordova,” Change.org, link. ↩

-

“Re: Consider closure of the Bristol Bay commercial salmon fishery in 2020,” City of Dillingham Alaska and Curyung Tribal Council, April 26, 2020, link. ↩

-

Isabelle Ross, “As processors lay out safety plans, three more tribes call on Dunleavy to close Bristol Bay fishery,” KTOO, April 12, 2020, link. ↩

-

Pablo Arauz Pena, “What Alaskans learned from ‘the mother of all pandemics,’” KTOO, May 5, 2020, link. ↩

-

“1918 Pandemic Influenza Mortality in Alaska,” Alaska Division of Public Health, Department of Health and Social Services, link. ↩

-

Victoria Petersen, “100 years ago, Spanish flu devastated Alaska Native villages,” Peninsula Clarion, June 22, 2018, link. ↩

-

Betsy Andrews, “The Alaskan Salmon Industry Faces Off against COVID-19,” Food and Wine, May 19, 2020, link. ↩

-

Nina Lakhani, “Why Native Americans took COVID-19 seriously: It’s our reality,’” the Guardian, May 26, 2020, link. ↩

-

Mary Kate Burgess, “City of Cordova confirms first positive case of COVID-19 via a seasonal worker,” KTUU, May 8, 2020, link. ↩

-

Zachary Snowdon Smith, “Cordova reports second COVID-19 case,” the Cordova Times, June 17, 2020, link. ↩

-

Isabelle Ross, “Trident seafood worker the first positive COVID-19 test in Dillingham,” KDLG, May 16, 2020, link. ↩

-

Tyler Thompson, “Bristol Bay announces 3 additional cases of COVID-19 since Friday,” Alaska Public Media, June 1, 2020, link. ↩

-

Lex Treinen, “State reports large daily spike in nonresident coronavirus cases, with 18 positives,” KTOO, June 4, 2020, link. ↩

-

Morgan Krakow, “Whittier grapples with how to limit spread of virus after 11 cases emerge among seafood processor workers,” Anchorage Daily News, June 4, 2020, link. ↩

-

Nina Lakhani, “US coronavirus hotspots linked to meat processing plants,” the Guardian, May 15, 2020, link. ↩

-

Bristol Bay Seafood processor letter to communities, April 7, 2020, link. ↩

-

Joaqulin Estus, “Virus fears ease as Alaska salmon fishing season starts,” Indian Country Today, June 5, 2020, link. ↩

-

Estus, “Virus fears ease as Alaska salmon fishing season starts.” ↩

-

Alex Wigglesworth, “150 cannery workers bound for Naknek now in forced quarantine at LA hotel without pay, suit claims,” Anchorage Daily News, June 21, 2020, link. ↩

-

Wigglesworth, “150 cannery workers bound for Naknek now in forced quarantine at LA hotel without pay, suit claims.” ↩

-

Daniel Costa, “Feds correct to ban Alaska fish processing jobs from J-1 visa program,” Anchorage Daily News, June 29, 2016, link. ↩

-

Michelle Theriault Boots and Marc Lester, “In Alaska, young foreign workers on ‘cultural exchange’ visas wash dishes and make hotel beds,” Anchorage Daily News, August 13, 2016, link. ↩

-

Julia Preston, “Company Banned in Effort to Protect Foreign Students from Exploitation,” New York Times, February 1, 2012, link. ↩

-

Elwood Brehmner, “Alaska fishing community takes precautions as it prepares for salmon season,” Anchorage Daily News, April 2, 2020, link. ↩

Jen Rose Smith (dAXunhyuu [Eyak]) is an assistant professor in the Geography Department and American Indian Studies Program at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.