Few people are aware that the house designed by Mexican architect Luis Barragán—known today as Casa Barragán—was designed originally for not just one occupant but two. Similarly, few know that this house, built in 1948, was not only Barragán’s residence but also the studio where he tested ideas and designed many of his best-known works. In 1982, reflecting on several of Barragán’s projects, American author and architectural historian Esther McCoy referred to his architecture as the result of a beautiful contradiction: that of a seeming calm that contained the effervescence of memories beneath.1 And indeed, visiting this house on General Francisco Ramírez Street in the historic working-class neighborhood of Tacubaya does reveal a contradiction, though not the one pointed to by McCoy.

In a 1987 interview by architecture critic Joseph Giovannini, McCoy spoke of the work of several contemporary Mexican architects, including the house of Luis Barragán, which she had first visited in 1951.2 In this conversation, McCoy traces the influences that can be found in his work, defining Barragán’s architectural style as “a cross between Corb and the village churches,” making reference to the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, who Barragán allegedly met during one of his extended stays in Europe.3 To describe this unlikely combination, she goes on to coin the term “Corbusian regionalism,” a mixture of Barragán’s “tropicalization” of the ideals of architectural Modernism and his reinterpretation of church and monastery architecture. Even more revealing, further on in the interview, Giovannini asks McCoy whether she also considered Barragán’s style to be informed by the architecture of Mexican ranches, a modern and more politically correct way to refer to haciendas.4 In an almost disparaging tone, McCoy responded that there was nothing “rancho” about Barragán, adding no further comment.5

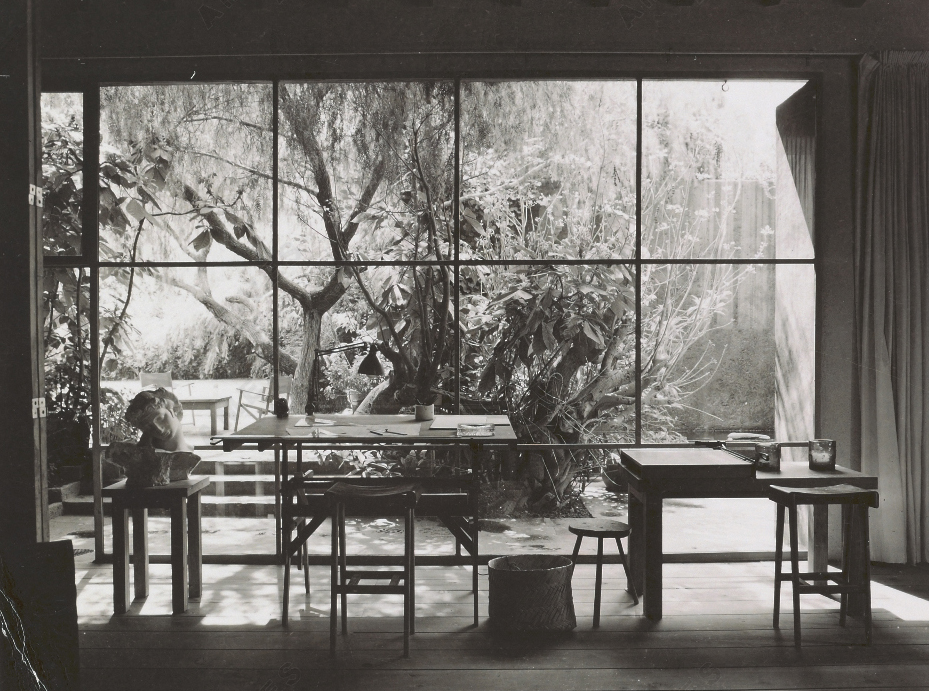

At first sight, it is true that there is nothing manifestly “rancho” in the architecture of Barragán. His own house, for instance, is filled with windows of all types and sizes that allow for natural light to shower its interior spaces, in sharp contrast to traditional hacienda architecture that tended to be more enclosed due to the construction techniques employed and environmental conditions it protected against. Even more distinctive, it was perhaps Barragán’s innovative use of traditional materials—the vivid colors with which he painted walls and his modern take on traditional Mexican residential decoration—that blocked McCoy from seeing further.

But one critical aspect of the house, overlooked by McCoy, is the role and configuration of its service spaces. Even though Barragán is understood to have led a life of relative solitude, he was nevertheless consistently accompanied by the people who served him. Until this day a common practice among upper-middle and upper classes in Mexico, millions of households in the country have full-time housekeepers. The role architecture has played in the continuation of social discrimination and in the reinforcement of poor working conditions in Mexico throughout the twentieth century—especially in residential design—should not be underestimated.6 Looking closely at these service spaces reveals the relationships Mexicans have constructed as a society, with architects as accomplices, between housekeepers and their employers. And since service rooms have long been a requirement of the residential real estate market in Mexico, no architect, regardless of their fame or position, can avoid their expected inclusion. In Casa Barragán, the architect was both designer and occupant, and he wasn’t alone.

After returning from an extended trip to Europe in 1925, considered to be a watershed moment in his career, at the age of twenty-three Barragán began practicing architecture in Guadalajara.7 His first commissions were private homes located within a few blocks of each other in the traditional neighborhood of Colonia Americana. These homes, designed and renovated for prominent public figures, all share an austere but graphic quality. They were heavily influenced by the haciendas of Jalisco as well as by the Moorish architecture Barragán saw during his visit to Spain—specifically to the Alhambra villa and Generalife gardens in Granada.8 Many of the formal and spatial qualities of the Alhambra and Generalife—the multilevel patios and walkways, the solid walls around courtyards and gardens, and the open arcades—can be found in the architect’s early work. After almost ten years practicing in his hometown, at the end of 1935, Barragán moved to Mexico City, leaving his family behind so he could build a career in the country’s capital.

From one perspective, the Mexico of the early twentieth century in which Barragán was raised was composed primarily of two social groups: a vast working class and a small, masculine elite. Just as it had been established almost four hundred years earlier during the colony, the employer of the 1900s was still typically either Spanish or a descendant of someone who was, while his employees tended to be of indigenous origin, descendants of the people who for centuries had worked the land. Despite the government’s efforts to modernize—specifically through the enactment of the new Ley Agraria and the Constitution of 1917—the Mexico of the turn of the century was still dependent on latifundios, agricultural lands whose products were mainly destined for export.9 The system of latifundios was primarily composed of a type of plantation known as the hacienda. These originated in land grants given by the King of Spain during the conquest of Mexico to Spanish conquistadores in exchange for social and military services as representatives of the crown in the so-called New World. In order to recruit its workforce, the new landowner, or patrón, would turn to the nearby communities offering its members work in exchange for food and a roof under which to sleep, a proposition that often represented the best opportunity for their families’ survival. As such, the system of haciendas was a fundamental part of the social and spatial order introduced under colonial rule and carried on all the way into the beginning of the twentieth century.

Production aside, most haciendas were composed of similar programmatic components: the main house and guest quarters, the servants’ quarters, stables, granaries, and corrals. Perhaps the most unique of these components was the “tienda de raya”—literally meaning “line shop”—a monopolistic credit establishment owned by the patrón where workers were forced to acquire basic goods for their subsistence. Since there was no real currency inside haciendas, workers would get paid in “scrip,” pieces of paper with a pre-assigned value, which they could only exchange for goods at the store inside the hacienda property.10 The total amount spent at the end of the month in the “tienda de raya” would be discounted from the workers’ already meager salaries, resulting many times in lifelong debts with the patrón that further increased their dependency.11

With the objective of having full control over the workers’ lives, the programmatic components of haciendas were expanded to include a school for the workers’ children and even a chapel. A resident priest—another loyal servant of the patrón—ensured the transmission of the evangelical message, first disseminated more than two centuries before his time during the Spanish colony while also continuing to reinforce the bond between power and religion. Graveyards were also commonly found inside these complexes, transforming them into small towns that workers would literally never need to leave.

Before Barragán’s generation, few well-known Mexican architects had looked for inspiration in the popular architecture of their own country.12 On the contrary, starting with the Spanish conquest and continuing into the early 1900s, the common practice was to turn outside Mexico in the search for ideals of beauty and new modes of living. As a result of this phenomenon, during the early decades of the twentieth century, all historic Mexican architectural traditions—especially those of the pre-Hispanic period, but also those imposed during the Spanish colony—were disparaged by the elites. At the time, due to the influence of the regime of Porfirio Díaz, the small sector of the population able to commission architects looked to the Beaux-Arts emanating from Western Europe, specifically France, as reference.13 In a country characterized by harsh social inequality, this duality found throughout Barragán’s oeuvre is the first of a series of notable contradictions: while his architecture is in many ways a reflection of Mexican folklore—the country’s popular beliefs, customs, and traditions that emerged from the encounter of the pre-Hispanic and the colonial—it is also inevitably imprinted with social protocols of the highly conservative Mexican elites.

For some residential architects during the first half of the twentieth century, to include service spaces would seem to contradict modernism’s progressive principles. Hoping to reconcile with the technological and social advancements of the time—including the emergence of labor unions, legal workers’ rights, and the growth of a middle-class and white-collar labor force—spurred many to reconsider the role of service spaces inside the home and deem them obsolete. However, service spaces have remained hidden in plain sight in many canonical modernist buildings. This misalignment with the ostensibly progressive aims of much of the modern movement’s discourse points to the movement’s internal contradictions. In Mexico, these contradictions are particularly striking in residential design, where architectural Modernism was implemented primarily as an aesthetic choice—not necessarily as part of a deeper social paradigm change.

Casa Barragán is no exception. By analyzing the configuration of its spaces in plan and section, one can note the discomfort service areas seem to have caused its architect. The architectural drawings reveal what can only be intuited while visiting the house in person: Barragán purposely segregated all service spaces away from the rooms he occupied, especially those considered private. He achieved this not only by keeping them physically at a distance but also by deliberately hiding them from clear sight. The areas occupied by housekeepers were squeezed to their absolute minimum, split into two segments—one on the ground floor and one on the third floor—and connected vertically through a slender and hidden spiral staircase. The first and most important of these service spaces was without a doubt the kitchen, the space where the women working for Barragán spent most of their time. Located on the ground floor adjacent to the party wall abutting Casa Ortega—the first house designed by Barragán for himself in Mexico City—both the kitchen and the service staircase are pushed alongside the garage, which allows for independent access from the street.

The same scheme is followed in the spatial arrangement of the second floor, where the master bedroom; dressing room; cuarto blanco, or “white room”; guest bedroom and bathroom; and personal study are located.14 These rooms constrict the size of and access to the service staircase that directly connects the ground and third floors, where the service bedroom and bathroom are, thus preventing housekeepers from having direct access to Barragán’s most intimate spaces. The decision to block any entrance from the service staircase to the second floor resulted in a back of house composed of inefficient circulation routes. For example, whenever a housekeeper needed to go from the third floor to the second, she had to first travel to the ground floor kitchen and then back up through the main staircase. This organization may have provided spaces on the second floor with privacy, but it also generated the potential for increased interaction between server and served in other areas of the home. On the top floor of the house, the service areas expand to take almost a third of the area of the rooftop, which was separated from Barragán’s private terrace by high walls. This might seem generous but should not come as a surprise, since Mexican architecture has traditionally reserved rooftops for the work of housekeepers, primarily due to the fact that this is the place where clothes are washed and hung to dry.

Similarly, looking at the elevation of the house from the garden with its different window sizes and treatments reinforces the idea of a calculated segregation of the service spaces and its users from the rest of the rooms. The interior façade that overlooks the garden gives a clear reading of the progression from the most public of Barragán’s spaces on the left—the living room with its large square window—to the least public room on the far right—the kitchen with its small reticulated window.15 Furthermore, the kitchen window is composed of translucent, textured glass, allowing for only natural light to enter this space and for its users to be nothing more than a blurry image from the exterior.16 And while it is important to note that the working conditions and the quality of the spaces in the service rooms of Barragán’s house were more humane than those in traditional haciendas, the spatial operations remain the same.

Take for instance Le Corbusier’s Villa Stein completed in 1927. In this case, the service bedrooms are separated from the main public areas of the house on its fourth and last level. They are open to the roof garden, Corbusier’s fifth point, and are easily accessible to all residents. The two service rooms have windows to both the front and back façade, making them visible from the main access and garden. In the case of Mies van der Rohe’s Villa Tugendhat, completed in 1930, service areas and bedrooms are situated with comparable ease. When analyzing its ground floor plan and the spatial sequence from the pantry and through the kitchen, an enfilade of service spaces culminates in a service bedroom, which contains two twin beds looking toward a large window. In this case, the path from public to secluded service spaces is fast and straightforward. The service areas are in proximity to the most public spaces of the house as well as those inhabited by the owner, all positioned on the same floor and divided by a single wall. Interestingly, other residential projects by Barragán of the same period, including Casa Prieto López (1947–49) and Casa Gálvez (1955), take a similar approach to the placement and access of service spaces, which is far more direct than in Casa Barragán. In these examples, spaces such as the laundry room and service bedroom are accessed through minor patios or garages, which are, in turn, connected to common spaces of the house via simple staircases and corridors.

But, similar to the way service areas once operated in haciendas, in Casa Barragán these spaces and their occupants were concealed from the public eye via compartmentalization. These operations were made possible through the deployment of specific architectural devices—foyers, corridors, walls, and doors—rendering housekeepers invisible all while keeping them at a convenient distance for when they might be needed. Particularly relevant to the practices of segregation implemented by Barragán in his house are a series of airlock-type anterooms of different scales positioned in between public and service spaces. By inserting these transitional spaces into an already complex circulation system, Barragán added an additional layer of separation between public and private. Bodies were required to stop and turn upon entering a space, which slowed down foot traffic and restricted sight lines. The compartmentalization of rooms characteristic in Barragán’s work, taken to the extreme in the design of his own house, plays a double role: It not only acted to conceal the service spaces but also provided the rest of the rooms in the house—specifically those occupied by him—strict control and privacy.

The regimen of control put in place by Barragán did not stop at the level of fixed architectural elements. The placement of furniture and interior objects such as artwork, screens, and religious paraphernalia reinforced the perception of seclusion and privacy in the house’s interior. Of particular relevance to this practice are glass gazing balls, one of several ornaments Barragán allegedly discovered through his friend, artist, and aesthetic consultant Jesús Reyes Ferreira.17 Barragán was known to place gazing balls throughout his home, typically against walls and near areas of transit, such as corridors or doorways. In doing so, these reflective orbs allowed him to capture the reflection of anyone coming in through a door behind him and avoid sudden interruption.18 Specific works of art played a similar role, such as the famous Goeritz square gold-leaf painting hanging at the top of the main staircase, with its blurred reflection of light and image. Other elements like free-standing screens—used by Barragán in lieu of airlock-spaces when these were not architecturally present—could be found throughout the house. They were placed at the entrance of select rooms (one can even be found in the access to the service bedroom) in order to block any direct interior gaze as well as to deflect access.

Barragán’s discomfort in public and efforts to set himself apart from others, both physically and ideologically, have been widely documented.19 His evasion of interviews, speaking to an audience, and established design trends is popularly explained by framing him as a solitary genius who pursued introspection in order to foster his most creative self. However, the regimen of control Barragán designed and implemented inside his own home cannot be attributed solely to his apparent unease with the public sphere. Casa Barragán’s tightly choreographed sequence of spaces and objects—a true total interior—implies he did not feel safe outside the confines of his own home and experienced a similar unease while inhabiting it as well. A premeditated and designed effort to protect himself from unwanted human contact inside his home was a lifelong project. Raising and extending walls, closing up windows, and rearranging furniture were all operations Barragán deployed consistently during the four decades he inhabited the house.

Perhaps one of the contradictions that fascinated McCoy, Barragán embodied the personas of both a dandy and a monk. Throughout his life he maintained written romantic correspondence with several women who he was also known to shun. In addition, Barragán’s heterosexuality has been questioned by historians and curators in recent years based on several observations: his friendships with openly gay men,20 the fact that he never married or had children of his own, his self-proclaimed devotion to the profession of architecture above all else, his rare public appearances and interviews,21 and even an alleged exaggeration of his religiousness to deflect discussion of personal life.22 And while none of these claims point to a single sexual identity, they do reinforce the image of a man who guarded against showing himself both in and to a public.23

The architecture of Casa Barragán is autobiographical and, as such, a reflection of his convictions and contradictions.24 With its labyrinthian circulation, its characteristic play of spatial compression and expansion, and its precise use of decorative objects ultimately served as personal armor—a kind of counterarchitecture to the trends of its own time, both local and international.25

Of the photographs taken by Timberman, there is one that is unique. This photograph documents McCoy poised at the top of the famous volcanic-stone stairs of the entrance hall (completing the void that perhaps spurred her contradictory feelings) and captures the back of a uniformed woman below her.26 This anonymous woman picking up the phone—perhaps as part of her duties or maybe just because the patrón was not home, is believed to be a woman named Ángela, a housekeeper who worked for Barragán when McCoy visited the house in 1951.27 Accident or not, this photograph shows a glimpse of one other figure that lived under the same roof as Barragán, the woman who helped him with the cooking and cleaning and who later took care of him.

Barragán did not write or theorize at length about his architecture, and thus, apart from his buildings and drawings, he did not leave behind any comprehensive intellectual testimony. However, glimpses of his thinking can be found in the few lectures and interviews he gave throughout his career. During one of these conversations, he expressed a phrase that could give meaning to the feeling McCoy felt when first visiting his house. He began, “mi casa es mi refugio” or “my house is my refuge” and continued, “an emotional piece of architecture, not a cold piece of convenience.”28 This phrase might contain not only the logic for the design of his house but also a fundamental part of the design principles of his work. The house served solely to protect Barragán—not only from the inclemency of the weather and the city but also from unwanted social interactions. In 1980, during his acceptance speech at the Pritzker Prize ceremony at the Dumbarton Oaks Museum in Washington, DC, Barragán listed his eight design principles. The fourth was “solitude,” of which he said, “Only in intimate communion with solitude may man find himself. Solitude is good company and my architecture is not for those who fear or shun it.”29

Achieving his appreciated solitude, however, came with a price. Informed by ideologies of inequality, the architecture of Casa Barragán perpetuated discriminatory practices on one hand and protected its main occupant from them on the other. Ultimately, this contradiction is drawn with lines of class, race, and gender. Barragán held a position of power that enabled him to design a total interior in which to reside, a condition that he worked to perfect over forty-one years. Those who served him were confined to the spaces they were given.

After Barragán’s death in 1988, his house became a museum. Foreseeing this, Barragán left one stipulation in his will regarding the future use of his home: he would allow for his last housekeeper, Ana María Albor, to continue living there for as long as she wished. As a result, all service spaces of the house—kitchen, laundry room, service patio, and bedroom—were given to Albor, who continues to live and work there today.30 While Barragán’s testament stipulations were undoubtably concerned with the welfare of his employee, the act is double-edged. By accepting Barragán’s gift—through desire or necessity—Albor continues to be rendered invisible by the people she serves. Much like the “tienda de raya” credit system found in haciendas, this “gift” extends her dependency on them far past the life of her original patrón. Paradoxically, the architectural practices rooted in colonial histories of segregation and oppression have allowed for her to live within the iconic home in undisturbed seclusion, hidden inside the walls of an otherwise public-by-appointment museum.

Postscript

In 2018, almost a century after the end of the Mexican Revolution, Mexico’s Supreme Court ruled there was no constitutional reason that domestic workers should be denied affiliation with national social security programs; to deny them this basic labor right would be considered discrimination. Consequently, on December 5 of the same year, the door was opened for the first time in history for 2.4 million domestic workers—most of whom are women—to enter the formal economy. As a provisional measure, the contribution of employing families to the social security system in favor of their housekeepers is still voluntary. Once the pilot program becomes law, its implementation will no doubt have long-lasting effects on the lives and security of domestic workers around the country, though its impact on the residential real estate market and the discipline of architecture at large in Mexico is still to be seen.31

-

In a letter to Barragán dated November 9, 1982, McCoy wrote, “How true you have always been to your genius, dear Luis. And in doing so I think that you above all others have been truer to Mexico. You celebrate Mexico with a Doric calmness; but infinite memories of place seem to seethe beneath the calmness.” McCoy to Luis Barragán, November 9, 1982, in Esther McCoy papers, 1876–1990, bulk, 1938–1989, Archives of American Art (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution). ↩

-

Joseph Giovannini, “Oral History Interview with Esther McCoy,” June 7, 1987–November 14, 1987, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, link. ↩

-

Giovannini, “Oral history interview with Esther McCoy,” link. During the 1920s, Barragán traveled extensively throughout France, Spain, Italy, Greece, and the north of Africa. In 1931 while living in Paris, Barragán attended some of Le Corbusier’s famous lectures, during which they are believed to have met, although the specifics of this meeting are not known. ↩

-

Haciendas—also known as latifundios—were large profit-making estates owned by Mexican elites outside of urban centers in which millions of indigenous people worked for very little or no compensation. ↩

-

The exact exchange reads as follows:

Joseph Giovannini: “There was a certain amount of the rancho in there too, wasn’t there?”

Esther McCoy: “No, not in Barragán. No, no rancho. None, none whatever.”

JG: “Cancel that.”

See Giovannini, “Oral history interview with Esther McCoy,” link. ↩ -

In the April 2012 article “Desde la arquitectura, la discriminación” included in the Mexican journal Nexos, architect Arturo Ortíz Struck wrote on the role architects play in the continuation of socially discriminatory practices in Mexico. Even among highly regarded firms, there is a tendency for architects in Mexico to design service rooms that are located in the most undesirable areas of a house, and that are therefore humid, cold, not naturally lit, or well ventilated. Arturo Ortíz Struck, “Desde la arquitectura, la discriminación,” Nexos, April 1, 2012, link.

Luis Barragán led a private life. He had few close friends, never married, and did not have children. Nonetheless, two key aspects of his life are widely known. The first, his profound religiousness, is linked with his upbringing in the conservative region of North-Central Mexico known as El Bajío. The second, that he closely guarded his personal life against public intrusions, was enabled in many ways by the architectural qualities of his home.[^8] Born in 1902 into a wealthy and observant Catholic family of local landowners, Barragán split his childhood between the neighborhood of Santa Mónica in Guadalajara, the capital of the state of Jalisco, and the Hacienda de Corrales, a commercial estate owned by his father in the vicinity of Mazamitla. Almost without dispute, Barragán’s characteristic style has been attributed to the experiences he had growing up in these parochial towns, as well as to the trips he made to Europe later in his life. And while these theories are well founded, it is necessary to look beyond his signature color-saturated walls and understand that Barragán’s architecture is not solely the reinterpretation of local aesthetic traditions but also the carrying forward of spatial operations and their inbuilt social structures, which had emerged centuries prior. ↩ -

Emilio Ambasz, ed., The Architecture of Luis Barragán (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1976), 105. Published in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, June 4, 1976–September 1, 1976. See Juan Palomar, “The Alchemist of Memory,” in “En el Mundo de Luis Barragán,” Artes de México, vol. 23, no. 1 (April 1994): 92–95. ↩

-

Antonio Riggen, Luis Barragán. Escritos y Conversaciones (Madrid: El Croquis, 1996).

The social inequality that reigns over contemporary Mexico is not only rooted in the rigorous caste system introduced by its Spanish conquistadors during the sixteenth century; pre-Hispanic cultures that inhabited the region many centuries before the arrival of the Spanish crown also operated under a strict social hierarchy. The racially and socioeconomically coded discrimination inherent to such a system is rendered particularly visible in residential architecture. In this unique building type, both public and private spaces are designed for simultaneous inhabitation by people of different socioeconomic and often ethnic backgrounds. ↩ -

Several laws were passed during the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920). One of the most significant was the Reparto Agrario also known as Ley Agraria (1915), which mandated the redistribution of land previously owned by the patrón among the people who worked for him. ↩

-

To exchange scrip for goods, each worker was required to sign a record book that contained their names. It was common practice for workers to sign by simply drawing a straight line to stand in as a signature, as many were illiterate. ↩

-

More than three decades after the emergence of haciendas, with the 1910 Mexican Revolution the ruthless exploitation of workers within these estates saw its end. During this decade-long armed movement, revolutionaries such as Venustiano Carranza, Pancho Villa, and Emiliano Zapata traveled throughout the country with their troops under the banner “la tierra es de quien la trabaja” or “land belongs to those who work it,” sacking and burning every hacienda on their way, freeing the workers from their oppressors. As a result, land was restored to the workers and subsequently each patrón was allowed to own a maximum of 80 hectares of land, a relatively minuscule amount of land after some of them had previously owned areas comparable to small European countries. ↩

-

Roberto Aguilar, “A los 74 años, Luis Barragán, fue galardonado por su Arquitectura Popular,” El Sol de México, November 19, 1976. In his Pritzker Prize acceptance speech in 1980, Barragán explained, “The lessons to be learned from the unassuming architecture of the village and provincial towns of my country have been a permanent source of inspiration.” See Luis Barragán, Pritzker Prize Laureate Acceptance Speech, read by Edmundo O’Gorman (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Museum, June 3, 1980). ↩

-

Porfirio Díaz, a Mexican general and politician who served as president of Mexico for more than three decades (1876–1911, a period also known as the Porfiriato), touted France as the cultural center of the world and as explicit reference for the development of Mexico. During the Porfiriato, Díaz encouraged urban elites to become more cosmopolitan, pushing for the consumption not only of imported goods, art, and architectural styles from France but also for the embrace of foreign customs. ↩

-

In Jill Magid’s The Proposal, the artist narrates her arrival to Casa Barragán. She describes being received by the director, Catalina Corcuera, who shows her to the guest bedroom. According to Corcuera, this was “where all of Barragán girlfriends slept.” See minute 9:38 of The Proposal, directed by Jill Magid (Oscilloscope Laboratories, 2018). ↩

-

In the introduction to the August 1951 issue of Arts & Architecture dedicated to Mexican residential architecture, Esther McCoy writes, “one serious defect to a North American used to a servantless house is the cramped and characterless kitchen. It was not, however until the United States ran through its servant class that our kitchen became a pleasant room. In Mexico today the entry hall, boasting a rubber plant, is often larger than the kitchen. The criado, or servant house, may one day, let us hope, borrow a little space from the master’s large house.” See Esther McCoy, “Architecture in Mexico,” Arts & Architecture, vol. 68, no. 8 (August 1951): 27. ↩

-

Also of note is the slender volume positioned outside the kitchen and against the perimeter garden wall. At first it would seem like a simple service closet, as the unfurnished architectural plan found on the foundation’s website implies. However, looking at the ground floor plan included in the exhibition catalog of Barragán’s first solo exhibition at MoMA in 1976, one can note this space accommodates the house’s main gas tank as well as a service toilet so that those working for Barragán would not need to use the ground floor bathroom. See Ambasz, The Architecture of Luis Barragán, 117.

There is an alternative reading of Casa Barragán that, while informed by the historic social and spatial practices of the hacienda, lies more with the psychology of its architect. After all, as mentioned, service spaces were included in many iconic Modernist homes, as well as in other residential projects designed by Barragán, though to quite different degrees of separation. ↩ -

While the origin of gazing balls, also known as “yard globes,” can be traced to thirteenth-century Venice, in Mexico they are a staple of the Bajío region where both Barragán and Reyes were born and raised. One of the first uses given to gazing balls in Mexico was at cantinas and saloons, where they were used as a type of rear-view mirror to spot potential threats approaching through the entrance door. Roberto Tejada, “Sybarite’s Monastery: The Reyes Residence, Mexico City,” Art History Research 3 (2003): 85. Barragán might also have seen gazing balls at the Exposition internationale des Arts decoratifs et industriels modernes in Paris in 1925. A large, triangulated gazing ball was the central focal point of the modernist garden Jardin d’eau et de lumière shown at the exhibition. ↩

-

Evan Moffitt, “Uncovering the Sexuality and Solitude of a Modern Mexican Icon,” Frieze, March 18, 2019, link. ↩

-

Leonardo Díaz-Borioli has explained Barragán’s reluctance to be public as a premeditated act to construct his persona. See Leonardo Díaz-Borioli, “The Materiality of the Image: Photographic Mirages in the Practice of Luis Barragán,” Relaciones. Estudios de Historia y Sociedad, vol. 35 (Zamora: El Colegio de Michoacán, 2014). ↩

-

Artist Jesús Reyes, for example, fled Guadalajara in 1938 after being arrested during a raid at a private gathering in his own home being accused of “indecency”—a term used to define alleged homosexual activities. After being beaten by the police and humiliated publicly, Reyes decided to sell his childhood home in Guadalajara and leave to the more progressive capital. This story is one of many shared by artist Juan Soriano, an apprentice of Jesús Reyes Ferreira, in Roberto Tejada’s text. See Tejada, “Sybarite’s Monastery: The Reyes Residence, Mexico City.” Carlos Monsiváis, a recognized writer and journalist, also confirmed these details during a public event inaugurating a museum in Guadalajara in 2008, claiming that Jesús Reyes’s homosexuality and sexual preference was the same as that of other renowned men from Jalisco who at the time no longer lived in Guadalajara, naming various figures (however, not Barragán) who moved to Mexico City at the end of 1935. ↩

-

In his acceptance speech to the Pritzker Prize in 1980, Barragán had Edmundo O’Gorman—Mexican historian, longtime friend, and brother of architect Juan O’Gorman—read his acceptance speech, claiming “he didn’t know the English language well enough” to be able to clearly communicate his speech. ↩

-

While Barragán’s sexual orientation has been and continues to be questioned, very few Mexican scholars have seriously addressed these speculations. For the purpose of this investigation, the following sources have been referenced: Fernando Quesada, “The Reality of Fiction: The Eco by Mathias Goeritz,” Cuaderno de Proyectos Arquitectónicos 6 (2016); Tejada, “Sybarite’s Monastery: The Reyes Residence, Mexico City”; and James Benedict Brown, Harriet Harriss, Ruth Morrow, and James Soane, A Gendered Profession: The Question of Representation in Space Making (London: RIBA Publishing, 2017). ↩

-

One means of access to Barragán’s intimate world can be found in his personal correspondence, particularly in the letters he wrote to the women he dated. Barragán’s entire personal archive is now part of the Fundación de Arquitectura Tapatía Luis Barragán, founded in 1988 and located in the architect’s hometown. In the book En busca de Luis Barragán or In search of Luis Barragán, author María Emilia Orendáin studies his personal correspondence. In it, she writes: “Women of unconventional beauty, who in a double act Barragán longed for and avoided, desired and feared, with whom he was fascinated and deceived.” See María Emilia Orendáin, En busca de Luis Barragán (Guadalajara: Ediciones de la Nocha, 2004). ↩

-

Ambasz, The Architecture of Luis Barragán, 107. ↩

-

Related to theories of queer space, Aaron Betsky describes spaces of counterarchitecture as those that appropriate, subvert, mirror, and choreograph “the orders of everyday life in new and liberating ways.” In the case of Barragán’s home, however, these orders were revamped to have the exact opposite effect on people moving through its spaces while, one can only assume, providing Barragán a sense of security and freedom. Aaron Betsky, Queer Space: Architecture and Same-Sex Desire (New York: William Morrow, 1997), 26.

In 1982, five years before McCoy was interviewed by Giovannini and two years after the architect was awarded the Pritzker Prize, McCoy wrote a letter to Barragán recalling her first visit to his projects in Mexico City, initially his Jardines del Pedregal, and afterward his home.[^29] During this visit, she recalls, she was given a “gift” by Barragán: to be left alone for a few hours of “perfection” in his house together with American photographer Elizabeth Timberman.[^30] However, following this statement, McCoy goes on to explain that what she experienced in Barragán’s home was, in reality, conflicted. To evoke this experience, she quotes the French poet Remy de Gourmont who wrote that “[coming] face to face with genius was to feel a new shiver.” It is this shiver that she describes having felt while meandering through his home for what would later become the August 1951 issue of Arts & Architecture dedicated to the residential architecture of Mexico. As she would recall in her letter, this reflex was the product of both deep joy and sadness. A sadness—one could argue—that was produced in part by the overwhelming beauty of the house’s interior spaces but also by their “emptiness,” revealed in the photographs taken by Timberman, spaces devoid of eyes to contemplate them in all their glory. Only the eyes of religious icons and sculptures testified to the beauty of this idle scenery. At first sight, the “emptiness” experienced by McCoy and documented by Timberman might go unnoticed to someone visiting the house today since most contemporary architecture is photographed this way—deserted. However, in this case, the photographic series depicts what only Barragán could see in the privacy of his own home: not solitude but perhaps something closer to loneliness. The sadness described by McCoy in her letter might have been brought on by the sudden understanding that the “gift” given to her by Barragán—that of staying alone in his house—was, in fact, for her to experience the seclusion he dealt with every day. ↩ -

The subject of domestic labor in relationship to Casa Estudio Luis Barragán has been previously explored by Mexican architecture historian Juan Manuel Heredia. His 2014 text “Querido Luis” also includes this photograph as a figure. See Juan Manuel Heredia, “Querido Luis,” Arquine, February 13, 2014, link. ↩

-

This information was obtained through correspondence between the author and Catalina Corcurera, director of Casa Estudio Luis Barragán, in October 2016. ↩

-

Ambasz, The Architecture of Luis Barragán, 8. All translations by the author. ↩

-

Barragán, Pritzker Prize laureate acceptance speech. ↩

-

Luis Barragán died in his home in November 22, 1988, at the age of eighty-six after having stopped formally practicing architecture since 1983 due to health problems. In the following years, his house and personal archive fell under the direction of the Fundación de Arquitectura Tapatía Luis Barragán, while his professional archive was moved to Birsfelden, Switzerland to be administered and maintained by the Barragan Foundation. ↩

-

By December 2019, a year after the Supreme Court ruling, the National Institute for Social Security (IMSS) had affiliated 11,947 domestic workers to their list, 76 percent of which are women and 26 percent of which are currently working in Mexico City’s metropolitan area. During a news conference given on December 5, 2019, Zoé Robledo Aburto, head of the institute, stated the goal of the program was to “make visible one of the most invisible and ignored sectors.” “Casi 12,000 trabajadoras del hogar han sido afiliadas al IMSS hasta noviembre,” El Economista, December 5, 2019, link. ↩

Francisco Quiñones is a practicing architect and professor at Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City. In 2017 he cofounded Departamento del Distrito, an architecture practice that works at the intersection of politics, identity, and the built environment. Quiñones holds a master in architecture II from the Harvard Graduate School of Design and a bachelor of architecture from Universidad Anáhuac.