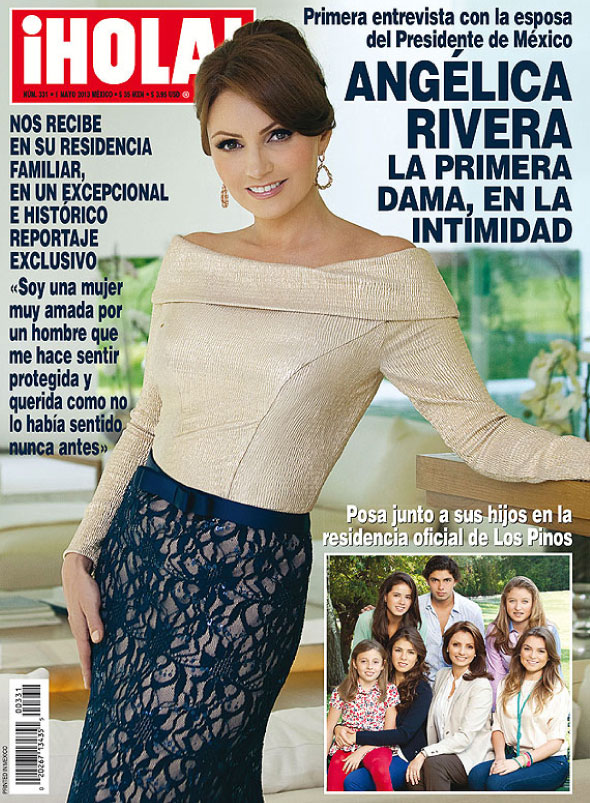

In May 2013 Angelica Rivera, the wife of Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto and a former soap opera actress, appeared on the cover of the magazine ¡Hola! The first lady was opening her house to the public in what the publication described as an “exceptional and historic exclusive interview”—a prescient headline preceding the political fallout that would surround the house and ensnare both Peña Nieto and Rivera in a controversy with diplomatic and national repercussions.1

Peña Nieto’s “White House,” as it has been labeled by journalist Carmen Aristegui, has been at the center of political turmoil that began with the disappearance of forty-three students from Ayotzinapa teacher’s college on September 26, 2014. Although the interview with Angelica Rivera had been published almost five months earlier, without raising much interest, it was not until Aristegui’s team published a story on the house questioning its origin, ownership, and ties with an important contractor that the magazine cover circulated massively in international and national press. By the time the story was published, the images of protests around Ayotzinapa were joined by claims of corruption regarding the Mexican White House.2 Magazines and newspapers printed glossy photos of the luxurious White House along with the images of the thin mattresses lying on the floor of the bedrooms where the students used to sleep. The Mexican White House has in this way become the embodiment of not only political corruption but of the harsh reality of social inequality.

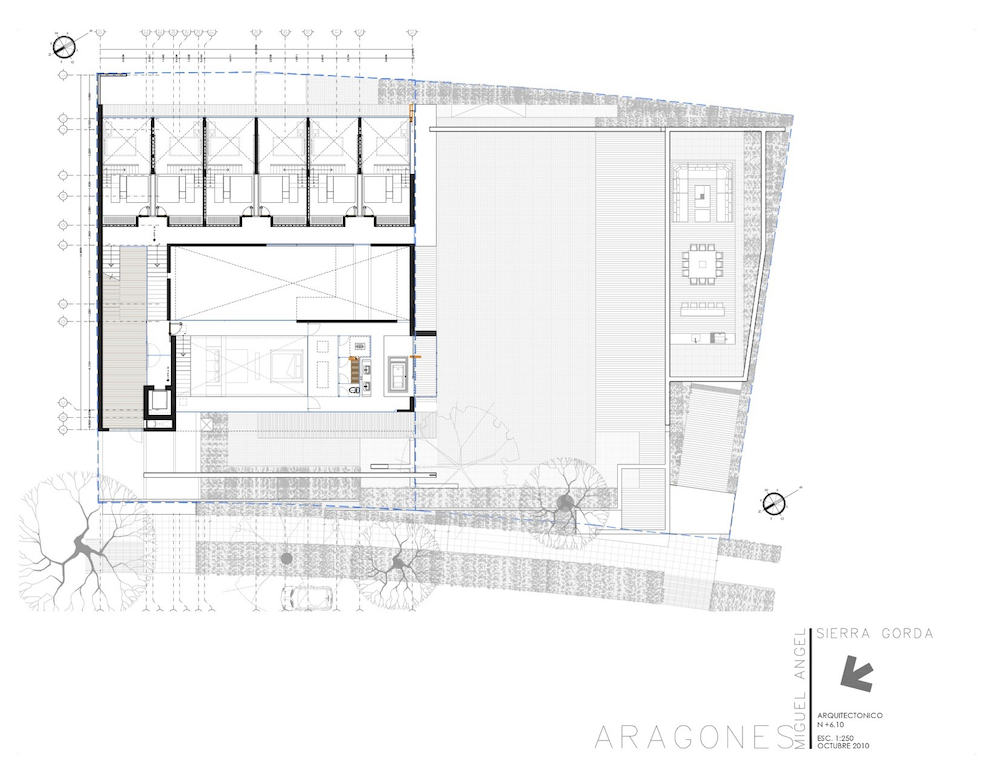

Built by Miguel Angel Aragonés in one of the most exclusive neighborhoods of Mexico City, the 21,000-square-foot mansion first appeared on ArchDaily.3 The blog post—a reproduction of the text that appears on Miguel Angel Aragonés studio website—frames the house within a contemporary lineage of Luis Barragán and his understanding of light. For Aragonés, light is the one element that “involves unraveling the concepts of space and time.”4 The press kit for the White House describes the harsh Mexican sunlight as the generator of the design—matter that can be transformed in order to “generate sensations, [and] atmospheres.” Light as a material can be controlled, softened, and harvested. On his website, Aragonés proclaims he is a self-taught architect who purposefully moves outside of the architecture circles and institutions. He is published and exhibited around the world, but does not participate in competitions, and rarely takes on clients.5 The use of blunt prismatic forms and his constant references to Barragán’s architecture seems to be the only characteristics linking his practice to the established Mexican design tradition.

In La Palma house (Aragonés’s name for the home), the rich, gentle light that bathes its white volumes by day gives way to a wild array of vibrant colors at night: the glow of violet, orange, blue, and magenta LEDs cover every inch of the interior surfaces. This is apparently the architect’s interpretation of Barragán’s use of light and color; where Barragán used reflections and natural effects to infuse a room with a tamed pink light, Aragonés uses LED lighting with automatic controls; where Barragán imprinted a white wall with a golden shimmer in his Tacubaya house, Aragonés leaves the walls naked and smooth to be delineated by zenithal rays from a sky window. On his website Aragonés explains the use of colored lighting as an act that “transforms the architect into a translator, an alchemist of sorts” by alluding to the distortion of natural light in wavelength and frequency in becoming LED lighting.

The central space of the house is a double-height living room all in white: walls, floors, furniture, and fabrics. The only textures in the house come from veins in the Carrara marble flooring, and the knots in the wood of furniture. For the most part, the images of the home appear to be untextured 3-D models, without a trace of human presence. Floor plans show six identical rooms (in order to accommodate the children of the previous marriages of the presidential couple), a master suite with two dressers and two full bathrooms, a spa area, a guest room, a family room, an enormous kitchen, a dining area, and finally a roof garden with a pool and a barbecue area. What is missing from the floor plans is the underground level that holds the service areas, namely the garage, the chauffeur and security room, the laundry room and the maids’ area. In the White House of Angelica Rivera, the servants must be rendered invisible, silent, and away, beneath the home. Their rooms receive little or no natural light—none of the upstairs’ luminous alchemy for them—and are entered directly from the garage so they can circulate without having to step into the house when it is not required.6

The White House of the presidential couple is a physical allegory of the Mexican social, political, and moral crisis; a clash between the contemporary luxury that money, power, and fame can bring, and the categorization of a low class that in Mexico has been transformed into a subhuman species without political, economic, or human rights. In his article, “Desde la Arquitectura, la discriminación,” architect Arturo Ortiz Struck describes the spaces of the domestic employees as heterotopias.7 Ortiz argues that it is in these domestic spaces where the structural social values of Mexican society can be perceived and tested. In Mexico, domestic employees work generally without the protection of any labor rights, they are not registered as employees, they do not have access to health benefits (less than 2 percent of the people working in this sector receive health care), and for the live-in workers their working day can extend up to twelve hours.8 What Ortiz describes is the negligence of architecture as a discipline in addressing the issues of labor and class inequality embedded within housing, and particularly within the Mexican home. His article references the designs of famous Mexican modern architects who have been associated with the redefinition of the Mexican domestic space, looking at the living and working spaces of domestic employees, and reading them through an anthropological lens. The architect, for Ortiz, becomes the translator of a deep-rooted social discrimination in Mexican society.9

Mexican artist Daniela Rossell is the author of Ricas y Famosas, a series of photographs that show wealthy Mexican women in their favorite part of their houses. The artist describes the women posing in these pictures as enacting “pre-written roles” that someone else has chosen for them. The reception of this work in Mexico was similar to the one received by the article in ¡Hola! These images, with their ostentatious wealth, were the faces of what could only be interpreted as corruption. Many of the women portrayed have ties with politicians from the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), a political party that ruled Mexico for more than seventy-one years, and that returned to power with current president, Enrique Peña Nieto.

According to Elaine Luck’s analysis on the reception of Ricas y Famosas, mainstream media saw Rossell’s work as “evidence of corruption and social inequality,” a view that provoked harsh criticism from Mexico’s intellectual circles, while art critics saw it “as a comment on consumer culture and its construction of feminine identity.” For Luck, these images are a contemporary take on Mexican costumbrismo, arguing that photography in Mexico emerged precisely as a means to classify and situate the individual into the different social strata.10 When interviewed in 2002, on the occasion of the exhibition “Mexico City: An Exhibition About the Exchange Rates of Bodies and Values” at P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center, Rossell defended her work, arguing that she was not portraying the women as objects or victims, or “as having a price tag”; she saw them “as having freedom.”11 However Ruben Gallo’s extensive critique of the work reminds us that all of these readings still leave out what makes these photographs historical—the complex lineage of the Mexican political regime—and that they render the relationships between power, history, politics, and society visible through densely packed images. In Rossell’s photographs, the setting becomes the subject of the work. The interior spaces bring together paintings portraying revolutionary Mexican heroes, artworks by important muralists, and decorative objects that reference key moments in Mexican history: the 1968 Olympics, political scandals, and moments of major national transformation. All this information is contained in one single image, evidence that these are not just rich women, but women who operate within power that has transformed the country.

One of the portraits shows Paulina Diaz, the granddaughter of former Mexican president Gustavo Diaz Ordaz—responsible for the infamous 1968 student massacre at Mario Pani’s Tlatelolco Square—in a luxurious living room filled with golden ornaments, dressed in tennis attire, and stepping over a dissected lion’s head.12 Another image shows an anonymous woman in a red gown sitting in her library, with a large painting of Emiliano Zapata appearing behind her, next to which stands her maid in uniform dusting the encyclopedias. Zapata (the symbol of the Mexican Revolution and a defender of the lower and indigenous classes), the figurines on top of the chimney, and the maid are for the woman in the portrait nothing more than objects within her domain. Images that have constructed Mexican identity appear repeatedly in these paintings, and, as suggested by Gallo, it is not likely that the subjects in this work are aware of their appropriation of these symbols, perhaps due to the fact that all of these symbols have been created within their realm—that of a political party claiming credit for the construction not only of the country but of the Mexican.13 Another recurrent appearance in Rossell’s work, and among the political elite, are soap opera actress and burlesque entertainers. Within the Mexican tradition, the fluid relationship between actors and politicians is not uncommon, be it through affairs, marriages, or the long-standing fraternization between the media empire Televisa and the PRI.

Even when Televisa and many other main TV networks attempted to contain the propagation of both Angelica’s house and the disappearance of the forty-three students, independent and social media became the fostering ground of a huge protest movement. The students from Ayotzinapa who were taken by municipal police came from a rural teachers’ college that has been fundamental in generating social activists and local political figures.14 The school functions as a self-sustained community in which its members are taught to be farmers in the morning and read Marx in the evenings.

The school has been attacked in the past, and its students have been killed by the government before. Yet when the police were given the order to “control them” as they were trying to make their way to Mexico City to commemorate another massacre—that of the students of 1968—they could not have foreseen that their actions would reverberate with such force—the labeling of the “43” along with the White House have made the presidency tremble with scandals.

With this in mind, it could be argued that the attention received by the White House of Angelica Rivera is due to its historical importance. It is not just that the house has been valued at around $7 million, or that there is a permanent presence of the Estado Mayor Presidencial (the Mexican equivalent of the Secret Service), or that the official presidential house has been completely renovated in order to accommodate a presidential family who allegedly does not live there, or even that the house in which the president and his family live is registered under the name of the owner of a company that has been awarded several building projects under president Peña’s term. Ostentatious political corruption is not a novelty in Mexico; what has really touched a nerve among public opinion is the house.

What can we learn from looking at the house and its publication? Clearly, this is not the same kind of space that appears in Ricas y Famosas. The house’s appearance is completely sterile; there is little art, no library, no books, no claims to the past or to Peña’s political ties. All we find is the woman and the architect. The first lady appears in ¡Hola! not only to show us her house, but also to sneak in the last pages of a piece of her work as president of the Citizen’s Advisory Council for the National System for Integral Family Development (DIF).15 In these photographs she appears along with her daughters and stepchildren embracing and playing with the less fortunate kids that are the raison d’etre of this institution. It’s more photo-op than real. The house, then, stands as the perfect embodiment of the simulation. Like the building, with its careful design and its render-like appearance, the presidential couple has been deemed by the media, as a fabricated fairy-tale custom designed for Enrique Peña’s future as president: the young, good-looking president with Mexico’s sweetheart on his arm.

Since the first day, the couple has been equally present in gossip pages and political headlines, making ¡Hola! a fitting choice for Angelica’s first public appearance as the first lady. Nevertheless, what was envisioned as a mouthpiece, a medium to humanize her family and her relationship, wrongfully shed a light on the house that Rivera described as their “true house,” the one in which they spent family time, and the place where they would come back to after the president’s term was over.

The office of Miguel Angel Aragonés did what has become the standard in the discipline: reached out to blogs, sent out press kits, gave press interviews, and even appeared on the national TV show “Los Despachos del Poder,” where he described President Peña Nieto as an intelligent and kind client. For his office, La Palma was one more house within a number of variations currently inhabited by wealthy families in Mexico City. Aragonés has translated Barragán’s take on the tensions between Mexican vernacular and modern architecture—spaces of nearly cloister-like self-reflection in a dialectical relationship with open landscaped patios—into a serialized set of large open geometries to accommodate the wealthy.16 He has managed to reduce the architecture of Barragán into a lighting strategy, draining the meaning, texture, and color out of Barragán, replacing his search for experience through volumetric relationships with the equivalent of the white cube.

The house, as it appears in ¡Hola! does not make reference to the family’s political tradition—although the president comes from an important political family from Estado de Mexico—or to Angelica’s career as an actress. There are no paintings of important politicians, actors, or even Mexican flags. The house seems to be devoid of references other than what the architect has given us, but further than that there are no references to its inhabitants; all we know from Enrique and Angelica has always come from magazines and paid stories on the evening news. In this way, the house reflects the desire of the presidential family to remain substantially opaque while still visibly powerful.

It also reminds us of that which is not portrayed: the servants, the poor, the other, those who are relegated to the last pages of a socialite magazine as objects of charity work. There are no paintings of Zapata, because this iteration of the PRI is as far from the revolutionary ideas of its foundations as it is possible to be. Peña Nieto’s political reforms attempt to finish what former president Salinas de Gortari’s started in 1994—the same year of the Zapatista uprising—that is, to grow the Mexican economy through a fierce neoliberal agenda by privatization of the nation’s resources, namely oil and gas. More symptomatic of Peña’s PRI, though, is not only having no affiliation with the Mexican revolution, but not even pretending to have it. The party in the past has at least laid claim to the illusion of a revolutionary inheritance.

The images of Zapata, of Marcos, and of Marx are still shown, not only among the descendants of the wealthy PRI politicians—who also own murals and paintings of important socialist artists like Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros—but in the walls at the entrance of Isidro Burgos’ rural school that still waits for the return of the forty-three students who were taken, who did not disappear, at the end of September of last year. That unforeseeable “event” that made the resurfacing of the article on Angelica Rivera’s house possible and turned it into a national scandal, ended with the cancellation of a massive train project.17 18 Those missing students that seemed to hurt the sensibilities of the presidential family when questioned in its regard, it is in their place that the image of Zapata rightfully lives.

-

“Primera entrevista con la esposa del Presidente de México, ANGELICA RIVERA LA PRIMERA DAMA, EN LA INTIMIDAD. Nos recibe en su residencia familiar, en un excepcional e histórico reportaje exclusivo.”¡HOLA! No. 331 (May 1, 2013). ↩

-

The story was first published on journalist Carmen Aristegui’s website, Aristegui Noticias, as a special investigation by Aristegui Noticias, the International Center for Journalism, and the Latin American Journalism Platform Connectas, and later that day presented on her radio newscast at MVS Radio. “La Casa Blanca De Enrique Peña Nieto,” Aristegui Noticias (November 9, 2014), aristeguinoticias.com/0911/mexico/la-casa-blanca-de-enrique-pena-nieto. ↩

-

Published in 2012 the house was labeled “La Palma,” following Aragonés tradition of naming his houses as a reference to the street in which they are located. “La Palma/Miguel Angel Aragonés” ArchDaily (November 18, 2012), archdaily.com. ↩

-

Taller Aragonés/Miguel Angel Aragonés, “Casa La Palma,” (October 2010), aragones.com.mx/es/detalle.php. ↩

-

Aragonés’ modus operandi is designing houses in which he will act as the first occupant and then sell to someone who can afford it. See Taller Aragonés/Miguel Angel Aragonés, "Cubo," aragones.com.mx/es/detalle.php. ↩

-

There are no visible openings in the ground floor plans published in Aristegui Noticias; the only possible sign of an opening is no larger than 80 square feet for an underground level of 7,254 square feet. ↩

-

Arturo Ortiz Struck, “Desde la arquitectura, la discriminación,” Nexos (April 1, 2012), nexos.com.mx. ↩

-

Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Geografia, “Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo 2013,” inegi.org.mx/sistemas/microdatos2/encuestas.aspx, accessed May 15, 2014. ↩

-

A year before Ortiz’s article, Peruvian artist Daniela Ortiz presented “Habitaciones de Servicio.” In this work, the artist analyzed the designs of high-class Lima houses built from 1930 to 2012, focusing on what she calls “service architecture.” The work takes the dimensions of such spaces and represents them in relationship to the bedrooms of the rest of the house. For this occasion, Ortiz designed a poster to be distributed in architecture schools around Lima with the legend “Maids room. There is no excuse for their location and dimensions.” See Daniela Ortiz, Habitaciones De Servicio” habitacionesdeservicio.com. These two works turn the spotlight of inequality not just on the architect but also on his/her education and share of responsibility in perpetuating segregation, discrimination, and social class distinctions. It is a self-reflecting exercise that has been recently advocated by many architects and critics toward not only class segregation but safety for building industry workers, responsibility for building in states that do not subscribe to the human rights bill, and the petition by Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (and recently denied by the American Institute for Architects) aimed at banning the design of solitary confinement cells and execution chambers. See: Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility, “Human Rights & Professional Ethics” (June 20, 2013), adpsr.org/home/ethics_reform. See also Raphael Sperry, “Death by Design: An Execution Chamber at San Quentin Prison,” the Avery Review no. 2 (October 2014), averyreview.com/issues/2/death-by-design. ↩

-

Elaine Luck, “Conspicuous Consumption and the Performance of Identity in Contemporary Mexico: Daniela Rossell’s Ricas y Famosas,” Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies vol.19 no. 3 (2010), 299–315. ↩

-

Rubén Gallo, “Voyeurism,” in New Tendencies in Mexican Art: The 1990s, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004). ↩

-

Daniela Rossell, Barry Schwabsky, and Luis Gago, Ricas y Famosas (México D.F.: Turner Publicaciones, 2002). ↩

-

For a detailed account of the transformation of the Mexican culture after the revolution under PRI, see Instituto De Capacitación Política, Historia Documental del Partido de la Revolución (México D.F.: Partido Revolucionario Institucional, Instituto de Capacitación Política, 1981); Luis Medina, Del cardenismo al avilacamachismo Vol. 18, (México D.F.: El Colegio de México, 1978); Roger Bartra, La Jaula de la Melancolía: Identidad y Metamorfosis del Mexicano (Barcelona: Debolsillo, 2012). ↩

-

Lucio Cabañas, the founder of the guerrilla group Party of the Poor, came from Isidro Burgos’ teachers’ college, as did the forty-three missing students. Isidro Burgos School has been implicated in political protests that on occasions turn to violent acts from part of the students. These actions have in this regard created polarized reactions towards the missing students, specially from the political class. ↩

-

Mexico’s central institution responsible for social assistance programs. “Angelica Rivera De Peña.” Angelica Rivera De Peña First Lady of Mexico RSS 092. Oficina de la Presidencia de Los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, http://angelicarivera.net/mi-historia/, accessed February 5, 2015. ↩

-

Humberto Ricalde. “Pensar, edificar, morar: una reflexión sobre Luis Barragán.” Revista de la Universidad de México 7 (2004), 32–42. ↩

-

The contractor for which (Higa) also built Rivera’s home. ↩

-

I refer to events in the sense outlined by Jacques Derrida. See Giovanna Borradori, Philosophy in a Time of Terror: Dialogues with Jurgen Habermas and Jacques Derrida (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013). ↩

Elis Mendoza has a degree in Architecture from the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico and is currently pursuing a PhD in Architecture at Princeton University.