In Boston Harbor, the small and shrinking Rainsford Island holds the remains of nearly 1,800 people.1 Nothing marks these burials, and the extent of the cemetery has not been confirmed. There are no headstones, no monuments—just a clearing in the grass amid rock and sand. We know these burials exist based on records from the City of Boston, which span the years 1800–1920 and can be located across a fragmented network: death certificates in the City of Boston Archives, veterans’ military records on Ancestry.com, and small markers in Mount Auburn Cemetery that serve as surrogate monuments to the graves that exist offshore.2 From the mid- to late 1800s, Rainsford Island was used as a remote cemetery for Boston: a potter’s field, a place to hastily bury the indigent, sick, or military dead in times of epidemic or war.3 It is estimated that 1,777 graves remain on the island; of these, 133 were military—nine who died in active duty during the Civil War and fourteen Black American veterans, at least one from the 54th Massachusetts Regiment.4 Beyond burial, islands of this kind were also often used to detain the mentally ill and quarantine the sick—all forms of moving the “unwanted” out of sight. The breadth of this history is not widely known, and Boston has no intention of resurfacing this long-settled past by marking, protecting, or disinterring the burials on Rainsford Island.5 Moreover, Rainsford Island is only accessible by private boat under authorization from the City of Boston, rendering any public gesture of memorial or maintenance an act of trespassing.6 As intended, the history of Rainsford Island really only exists if we care to look for it, and, as time passes, it becomes more and more likely that the memory of those buried there will not endure—that the last witness of Rainsford Island will know only a mass of anonymous earth, a wedge of land threaded thinly with grass and wildflowers, its history only guessed at.

I.

The circumstances of Rainsford Island speak to the contemporary state of cemetery practice—specifically, cultural anxieties about being remembered and how those anxieties are made material. There has long been an issue at the center of burial practice of how to translate permanence. We have relied on materiality to do this: the delineation of plots, the setting of stone, and the expectation that these things, these boundaries, will stay put. These conventions emerge out of an understandable impulse; it is important to us, almost compulsory, that some physical vestige or earthly extrusion exists beyond the body. It’s as if, by carving out space and filling it, we might be able to offset the absence left in death.

This material impulse—one grave to mark one name—is one that both serves and is symptomatic of a cultural commitment to individualism. This individualism in death lends a mirror to the living; it has resulted in the onset and prevalence of the many-acre garden cemetery, the dominant frame of burial in the United States, which, for its sprawling extent and metered placement of graves, imitates the suburban model.7 In their prototypical form, garden (or rural) cemeteries were small clusters of headstones organized according to blood or township. They were typically church-adjacent, constellating along major roads in burgeoning New England communities. In cities, cemeteries took the form of congested burying grounds and church crypts, until concerns for sanitation and lack of space brought burial to the city’s fringes.8 By the early nineteenth century, the first garden cemetery in the United States, Mount Auburn outside Boston, had been built, establishing the cemetery as a place where death was brought away from the city, masked in monument, smoothed over by the shade of trees.

Cemeteries that cropped up during this time—such as Mount Auburn and Green-Wood in Brooklyn, New York—are known for curating an atmosphere of tranquility, transforming the stillness of death into something attractive, marked by ease rather than distress, and drawing in a community beyond the bereaved, as cemeteries of this scale and spectacle were often frequented as parks before the creation of public parks themselves.9 This move toward garden cemeteries marks a transition from the harsh monumentality of the city-situated necropolis, which had shaped the memorial landscape of the ancient near East and later modern Europe. The garden cemetery maintains the grandness of the necropolis while softening its edges, scaling down huge tombs and mausoleums, incorporating the landscape, and moving the dead outside the city—a decision that more closely resembles the burial practices of other cultures, where rural or ancestral burial grounds are often destinations remote from social hubs.10 Other garden cemeteries throughout the United States, though often not as lush, ornate, or transforming, have inherited the scale and sense of limitlessness of their progenitors; most garden cemeteries span several acres and inter two centuries worth of remains.11

In recent years, the “limitlessness” of these expansive cemeteries has begun to fail. Boston’s three active cemeteries, all private, are projected to be full by the end of the decade, and Green-Wood, one of the largest cemeteries in America at 500 acres, is approaching full capacity.12 More concerning, it is nearly impossible to create new urban cemeteries, as undeveloped space doesn’t exist in sufficient quantities.13 Cities around the world have confronted this issue in varied, often haphazard ways: the City of London Cemetery has opted to reuse graves seventy-five years and older; Singapore’s only active cemetery limits burials to fifteen years, mandating the removal and cremation or reinterment of remains elsewhere; Mount Auburn has begun laying graves in the spaces between existing ones.14 The impulse here is to strain logistics in order to maintain custom. But, beyond logistics, the overuse of land in the development of cemeteries and quartering of identity into rows of graves speaks to a fragility that we feel about memory and mortality—that in order to feel that memory endures, it must be at a remove, individual, and cast in stone.

These conventions, though rigid, are not immutable. Despite our dependency on them for the last 300 years, they represent only one inflection of grief, one way of memorializing, and, importantly, they are not directly compatible with rising concerns of sustainability, nor do they accommodate those of constrained financial means. The cheapest option for a monument (a single stone marker affixed flat to the ground) at Mount Auburn Cemetery can cost upwards of $1,000, whereas single headstones across all cemeteries average about $3,000, which still excludes the cost of a burial plot.15 In affirming the class disparities of the living, contemporary cemeteries diminish the universality of death and memory. In “The New Civic–Sacred,” the architect Karla Rothstein explains how this relegation of death has splintered grief into a firmly individual experience, rendering death taboo and memory stranded: “The sequestration of funerary practices and spaces of memorialization veils discussion of [death] and atrophies our appreciation of mortal existence and sense of connection to generations past and future.”16 Rothstein argues not only that cemetery practice has become rote but also that, as a model for memorialization, it has ultimately weakened in its effectiveness in holding and translating memory across time. If the contemporary cemetery is one that can no longer sustain or take in our memories, what alternative is there?

The kind of burial that has shaped places like Rainsford Island—the mass, or nameless, grave—is inherently violent, defining a degradation of identity at best careless and more often intentional. Mass graves have historically been, and still are today, a mode of burial carried out upon occasions of disaster, neglect, and brutality—especially during war.17 Despite their proliferation during times of especial violence, their cruelty is part and parcel of the racist, classist, and queerphobic systems that make up everyday marginalization; this is especially seen in the way they deny the “individual,” reflecting who gets to be a subject and who is, instead, only subjected. Mass graves disturb, too, the sense of individuality that we have grown to expect from and associate with memorialization, allowing the remains of a body to diffuse into another, fraying the edges of identity. Places like Rainsford Island must contend with the format of the mass grave as a means of confining and erasing memory. But in its contrast to the hyper-individualism of contemporary cemeteries, can the history of cemetery islands point a way forward for the evolution of burial practice and for alternative expressions of memory? Is there a way to bring dignity to a practice that effectively limits the spatial imposition of burial? Is the way forward to disrupt the individuation of the subject at large, recognizing instead the body’s ability to join its greater more-than-human milieu upon death?

II.

Another cemetery island, Hart Island in New York, undoes some of our understanding about what customs memory must align with. The 100-acre Hart Island has received almost a million burials since its establishment in 1868, when New York cemeteries faced overcrowding; these burials represent a stratum of fraught history, a timeline of sickness and social ailment that has extended globally. Since its creation, the island has been used as a burying ground for overwhelming numbers of the sudden dead, especially in times of crisis. During the 1918–1919 Spanish Flu pandemic, both Rainsford and Hart Island were used as burying grounds, the most recent point of equivalence that can be drawn between the two.18 In the early stages of the AIDS epidemic, Hart received the bodies of those who were not claimed by family members, acting as a burial of last resort where stigma precluded any other. Burials on Hart Island have occurred as recently as during the COVID-19 pandemic, where the impact of global sickness on the island was, for the first time, heavily documented, yielding photographs of plain wooden caskets and figures in white medical suits tending to trenches in the earth. Despite the swells during times of epidemic, burials at Hart Island are no longer relegated to just the indigent and sick. It remains an active cemetery today, averaging about a thousand city-funded burials each year—accommodating people uninterested in or unable to afford the impractical cost of private cemeteries and monumental burial.19 While most cemeteries have been overwhelmed by now, Hart Island has managed its 100 acres amidst three epidemics for almost three centuries. Its once-filled northern shore has reopened for new burials—the remains once buried there have since frayed into the earth, and the old buildings that used to loom over the site (a crumbling asylum, a power station, a Catholic chapel molting away its once-colored glass) have been demolished, making room for 72 more acres of burial space.20 The result is an island that, like Rainsford, appears strangely untouched: a jagged flat of earth barely rising above the heavy blue of the Long Island Sound, a slender sweep of fields and fragments of woodland.

Like Rainsford, Hart Island’s apparent emptiness is one that betrays the truth of its fraught history. Before ownership shifted to NYC Parks and Recreation in 2021, penal labor sustained the island and its burials for 150 years under the ownership of the Department of Corrections.21 The incarcerated were assigned to various buildings, one of which, known as “The Pavilion,” was formerly a women’s asylum.22 This labor defines a period of exploitation for the island, where the forced digging and maintenance of graves was justified as a means of rehabilitation for the prisoners. Historically, burial on Hart Island has been due to a confluence of economic and social failings, and the City of New York has relied on the marginalized—its imprisoned—to bring resolution and rest to the equally marginalized—its poor, homeless, and sick, the majority of whom, in all groups, are people of color.23 In addition to the island being used as a site of detention for the mentally ill, it was used, from 1967–1976, as a site for rehabilitation from addiction. The conditions of this rehabilitation were similar to those experienced in “The Pavilion” and the prison workhouse, and residents—expected to work—were disciplined while struggling to overcome addiction.24 Hart Island’s treatment of the mentally ill and addicted is characteristic of the carceral system’s tendency to consolidate the marginalized—a tendency that was characteristic, too, of cemetery islands.25

At first glance, Hart Island suffers from the same history of isolation and neglect shadowing other cemetery islands. Here, our apprehensions about mass graves are legitimate, as they’ve been used as a tool of erasure for frequently erased groups, and the exploitation that occurred during the island’s penal era is not easily reconcilable with a sustainable future. In looking past the shadow of its history, though, we can see that Hart Island veils something much more complex than other cemetery islands: an active and unorthodox burial system, one that can accommodate burial endlessly. Beneath the surface of the island there is an intricate grid, a mass grave spread out in several clusters, marked sparsely with squat white headstones. This grid system emerged, in part, out of the tumult of the Civil War, when burial had to be fast and without decoration, and when bodies often never left the bounds of the battlefield.26 The quiet shame of poverty and illness may not have been seen as so dissimilar from the sobering aftermath of war, a “leave no trace” burial system being suited to each, which both carry an urgent desire to forget. Hart Island implemented this system in 1872, in the yet-to-be-settled fallout of the war, and it has remained in place ever since.27

The structure of burial on Hart Island is, from both a past and contemporary perspective, an innovative one; it is orderly and careful, documented and designed—a system in every sense. The infrequent use of monuments and the lack of subterranean infrastructure required by this system means that it is minimal in its material impact; remembrance is achieved through the documentation of bodies through photography, something that was unusual for the early 1900s, and the supplementation of those photographic records to written ones renders the system comprehensive.28 The system is also one of structural forethought: numbered caskets are spaced evenly to one another, laid in wide, uniform furrows of earth that intuitively delineate each grave.29 This homogeneity makes the finding of each plot easy even in the absence of headstones or other forms of surface markings. It also makes disinterment possible, depending on the state of the body’s decay, because, without the need for rigid methods of stabilization and through the use of caskets intended to disintegrate, each body is only entombed by a loose membrane of soil. This system relies on what might now be considered crude methods of burial—no embalming, no lacquered casket, no cement foundation to cradle the body: nothing to cut back against the corrosive reach of the soil. But Hart Island resists all the burial practices we’ve come to consider custom and dignified, representing a variant avenue of memorialization, one that has had time to develop and persist independent of tradition, and one that should not be assumed unethical. In truth, Hart Island’s burial system is one of the closest we can come to “green” burial—a burial that does not seek perpetuity, at least not in a material sense, and does not spoil the earth or air, even anticipating the eventual arrival of someone else in its place. The body thus becomes congregate with another, or several others, if the remains of the former are not disinterred—a reality that challenges both the division of contemporary death practice and especially the material “permanence” that has typically been an aspiration of other types of cemeteries.

In “The Future of Urban Cemeteries as Public Spaces: Insights from Oslo and Copenhagen,” the scholars Pavel Grabalov and Helena Nordh state that there is a “liminality” to cemetery landscapes, one that causes time to seem to move slower, memory to seem to hold.30 This idealism about the longevity of memory after death evolved with the garden cemetery. Today, cemeteries address the expectation of eternity in varying ways; many cemeteries, Mount Auburn included, offer perpetuity clauses for the upkeep of graves—that is, an additional price paid to ensure that the site’s staff will right, repair, and, in some cases, plant around a headstone even in the absence of any living descendant (who would normally be the one to solicit such tasks).31 Apart from well-endowed cemeteries like Mount Auburn, though, most urban cemeteries are fated to fall into disuse, and most grave markers, though made of stone, are fated to fall over, be overgrown, or disintegrate.32 It is another issue in tying memory to material—that to set memory in stone is to require the constant upkeep of that stone and the landscape populated by it, or else risk telegraphing the destruction of memory rather than its endurance. This is one problem brought to light by the circumstance of Rainsford Island: the island, in its state of placid ruin, cannot have its history publicized without becoming a testament to forgetting. Also, Rainsford Island is actively eroding, having lost 14 percent of its area since 1970.33 This renders any aesthetic rehabilitation for the island difficult to justify, which only further paralyzes intervention for the memory contained there.

III.

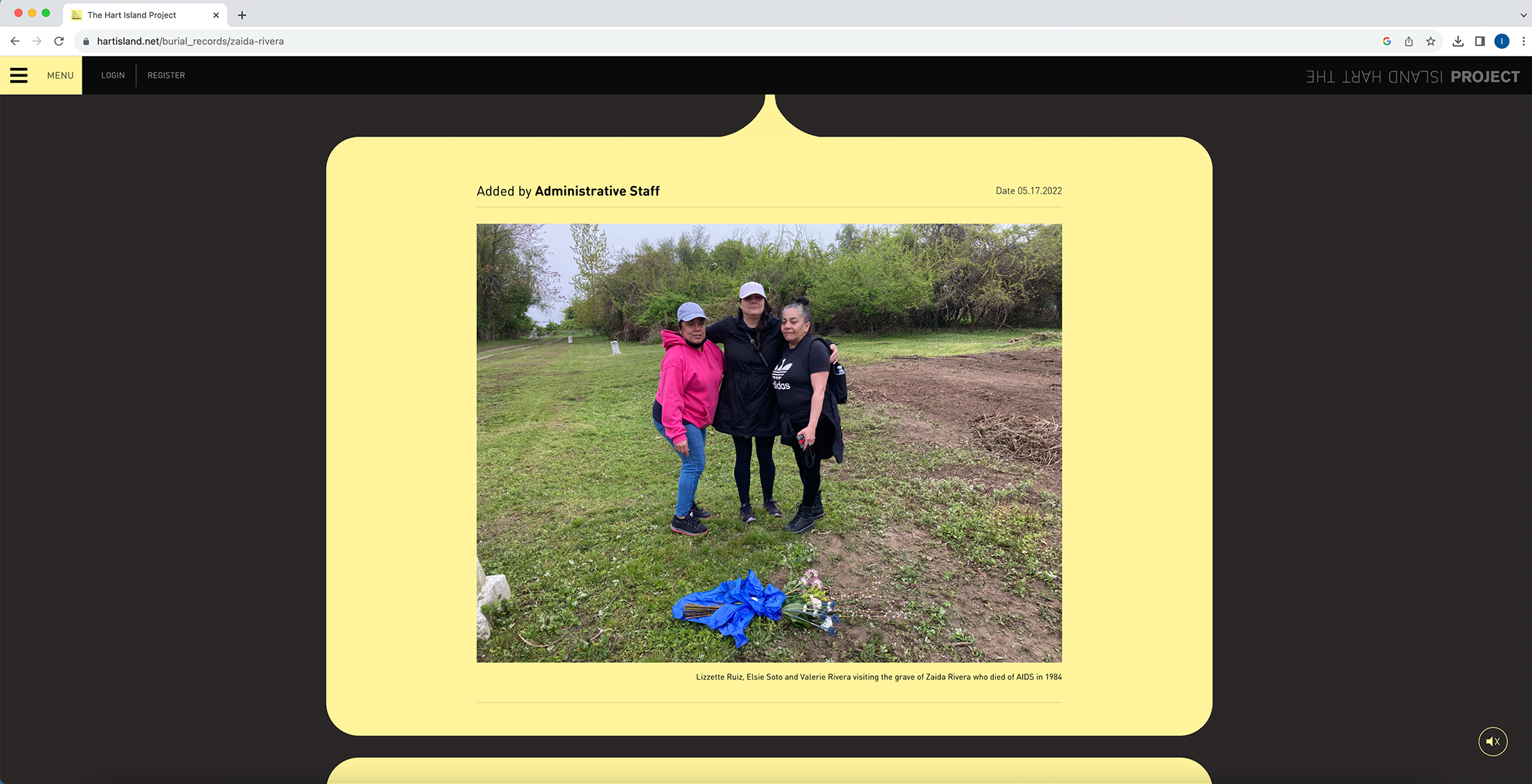

The Hart Island Project is a nonprofit organization dedicated to the documentation and dignification of those who rest there. Founded by Melinda Hunt, an interdisciplinary artist, the organization has helped Hart Island receive the maintenance necessary to develop beyond the tragedy of its history. Anyone, traveling by city-funded ferry, can currently visit without being closely monitored or surveilled by park rangers (as was previously required), and so the experience more closely resembles that of a typical cemetery, though perhaps heightened by the unique topographical makeup of the site; as Hunt states, “The island is much more intimate without the buildings, and it doesn’t feel like anything is dominating the site in a way that even typical cemetery monuments—headstones, sculptures—can feel dominating.”34

In both pushing for public access to the island and broadcasting its burial records, the organization treads two paths toward dignity: encouraging visitation, thereby stabilizing the island’s legacy within the landscape of New York City, and telegraphing that legacy outward, drawing the gaze of anyone, anywhere, in. This “telegraphing” occurs digitally; The Project’s “Traveling Cloud Museum” geolocates the individual identities making up the island’s mass graves, allowing for anyone with access to the internet to view the names of those interred, perhaps even to contribute stories or images about the individual, easing them out of anonymity. The Traveling Cloud Museum also counts the seconds since someone has been buried on Hart Island.35 In viewing the place and name of the interred, you are presented with a clock—a small line of text moving in the corner of the screen, spanning seconds to years. This clock does not aspire to eternity. Its counting ends once someone adds information about the person buried—a story, an image—and what remains are those words, those pictures: the abridged history of a person sustained in the gentle glow of a screen.

This feature is being worked into an augmented reality experience, one that will encourage visitation to the island and enhance how its users take in memory. Once implemented, anyone with a smartphone will be able to experience the site as an invisible cemetery, pointing their camera at a seemingly empty plot of land to elicit information about those interred there, even after their remains have eroded and someone else lies in their place. In many ways, the attitude toward burial on Hart Island hearkens back to the bygone practice of churchyard burial (the precursor to garden cemeteries), where the material fate of the body wasn’t as important because, in your proximity to the church and inclusion in its annals, you were in God’s care—a kind of immaterial security that we can return to through the format of the digital memorial.36

Hart Island, excluded from the codification of contemporary cemetery practices, has stood outside time, which makes it more capable of adapting to and balancing the material and immaterial demands of memory. The resulting confluence of digital and physical memorial is idealistic, even romantic: we can imagine the wonder of coming across a blank expanse of land that, when viewed through the lens of a phone, returns a registry of names and faces spanning generations: a limitless stratum of memory that fits within one’s grasp, where each name is decorated endlessly with pictures and stories, perhaps even videos and voice recordings—a way of depicting the dead with an archival breadth that attempts to match the range of being they would have had in life. But this anonymity-centric format does not necessarily eliminate, or even mitigate, the hierarchal tendencies of contemporary memorialization; just as physical memorials vary in accordance with money, the contribution of stories will ensure the surfacing of some identities while others may recede into deeper anonymity—the currency here being documentation. This format gives form to aspects of identity that, through simple headstones, are uncommunicable—one’s comprehensive history, appearance, and so on—conferring value to individuals based on their depth of information, the “fullness” of their story. To some, this may seem like a further splintering of memory in death rather than a convergence of it.

There are other issues that digital memorialization may face. The technology that allows for digital engagement with the dead is itself a material vessel, an infrastructure prone to failure. Likewise, the perpetuity of digital memorialization may be an illusion, given that, despite its ubiquity, it is impossible to predict how our use of the internet will change, or what devices will be required of us to engage with it.37 The maintenance of digital memorials, though assumedly easier to keep up with and less vulnerable than their physical counterparts, might also be unpredictable; without the obvious destructibility of stone, care for digital memorials may be seen as unnecessary, and digital memorials may experience equal or even more extreme neglect than physical ones.38 Other problems with digital memorialization are psychological: that digital memorialization divorces memory from materiality will likely be a huge deterrent for some people—even inspiring feelings of technodystopia in some—who may see this forsaking of the physical as a kind of second death.39 In their upward posture and perfect lettering, in the shimmering grain of their stone, physical graves are not only eye-catching but reassuring. They can serve not only as a monument to the memory of an individual but also, in their objectified beauty, as a totem of rebellion against death itself—a last declaration of defiance slow to decay. Terror management theory, which posits that humans must embed meaning in the abstract or immaterial in order to cope with the material failing of our mortality, emphasizes the psychological necessity for offsetting the physical destruction of human life through proportionally physical means.40 According to this theory, a way of managing the anxiety around physical death is to produce artifacts that contain aspects of identity that are widely applicable or appreciable, as in a national flag eliciting a sense of belonging, a work of architecture evoking universal awe, or a headstone drawing one’s eye, offering an etching of letters that demands to be read by anyone, indiscriminately, even centuries after its namesake has passed. These artifacts afford us a sense of “symbolic immortality,” the idea that some part of us is contained and made legible in cultural or material figures.41

If we consider the impetus for cemetery islands—that the exporting of death was, in the first place, an erasing of memory, of essence, through the displacement of the body—then we must recognize that to deny someone a monument or marker would have been to deny their memory this symbolic resistance against death. Part of ensuring this erasure was also to prevent the development of a true cemetery, at least one that was publicly accessible or desirable. On the nature of memorialization practices, specifically on outward displays of mourning, Grabalov and Nordh state: “While [mourning] practices engage with personal emotions of sorrow and grief, they are socially and publicly accepted and recognized in cemeteries. Through memorialization, private recollections become part of public history.”42 Here, Grabalov and Nordh are referencing the ability for mourning, a personal act, to contribute to a broader tapestry of history when performed in the context of a cemetery, where mourning and memory are amplified by the concurrent visitation of the bereaved. For cemetery visitors, the crossing of paths can refract mourning and memory into a shared, greater thing.43 In relegating the dead to an island like Rainsford or Hart, where people could not visit, where monuments could not be erected, the intention was both to erase memory and to suppress its transmittal, to give memory an edge. The act of visiting a cemetery, it can be argued, is a way of undoing this edge. To this end, is there a psychological value in the physical that cannot be simulated digitally? Does the scale of a cell phone, the distance of a computer screen, instead isolate memory, rendering memorialization an even more individual practice?

As highlighted by Hart Island’s Traveling Cloud Museum, digital memorialization inherits the material issue of unequally prioritizing memory, revealing the difficulty of the practice regardless of medium—particularly when that practice is dictated by a commitment to individualism. Perhaps digital memorialization, in its novelty, should not seek to model itself after the strict delineation of identity seen in contemporary practice. Contemporary and future cemeteries could instead embrace the palimpsestic nature of cemetery islands, where the compounding of bodies could be reoriented as identities becoming in conference with one another. This could be as simple as dedicating one memorial to several or even many people, a practice commonplace in instances of tragedy but rare in cemetery burial.44 In this case, memorialization technologies need not provide an exact imitation of the name-and-grave system. Perhaps there is a use for memorialization technologies to supplement committedly physical forms of burial and memorialization—a means of articulating or assisting a memorial rather than replacing it—but perhaps there is also a chance, in evolving the memorial landscape, to consider more communal forms of burial and memorial, especially when new memorial practices, born out of individualism, erode so easily into a social stratum.

IV.

There is no certainty in how cemeteries will evolve to meet rising pressures of space, sustainability, or inequity, or if there will be a consensus in this evolution. Adherence to custom and to materiality will not be broken overnight, nor should it necessarily be. In looking at the history of cemetery islands, we can learn more about the past and present of cemetery practice as a whole—the effective and ineffective aspects of the standard burial and headstone configuration—while giving shape to new strategies for memorialization in the future; these new strategies may look entirely unfamiliar to us, or, as is the case on Hart Island, they may unify old tactics with innovative ones—physical burial with digital memorialization, the material and immaterial in synthesis. Outside of finding a solution to the problems facing cemetery practice, though, it is important to direct our gaze to these islands to give dignity to such memory, which has, historically, been afforded none. In observing Rainsford Island in 1888, the author Moses Sweetser wrote:

[Here], Boston families sent members with dangerous infectious diseases: they were certain never to return; unfortunates rest within sight of the spires of their hometown; isolated on this dreary strand; allowed to drift down into the darkness of death uncomforted by their neighboring friends and relatives.45

It is hard to envision a memorial that might aptly capture the feeling Sweetser alludes to here—a memorial that can speak to the irresolution of a life pulled from its home, cut short by war or disease, or one that might evoke the feeling of standing on those thinning shores, looking out at the skyline of Boston and wanting nothing more than to close what would have seemed a short but insurmountable distance. It is an image, and feeling, that questions the nature of memorial practice: What are we hoping to do when we blanket a body with earth and dress the surface with stone? Are we hoping to undo the isolation of death, aptly capture the life of a person in an object, suspend the entire history of them in an instant of observation? There is no better memorial landscape against which to pose these questions than one that opposes typical modes of memorialization. Beyond tragedy, perhaps the legacy of the cemetery island is this: that cemetery islands can offer us an insight into the limits and potential of memorialization when stripped of all the customs we have come to know.

-

William A. McEvoy and Robin Hazard Ray, Rainsford Island: A Boston Harbor Case Study in Public Neglect and Private Activism (independently published, 2020), 94. ↩

-

McEvoy and Ray, Rainsford Island, 96. McEvoy details a process of personally searching out and recovering burial documents from the City of Boston and the various Boston psychiatric centers among which the mentally ill were frequently transferred. ↩

-

McEvoy and Ray, Rainsford Island, 7. ↩

-

McEvoy and Ray, Rainsford Island, 7. The 54th Massachusetts, an infantry regiment of the Union Army, saw the enlistment of Black American men during the Civil War. ↩

-

McEvoy and Ray, Rainsford Island, 114. Since the early twentieth century, calls for the disinterment of bodies or formal marking of the cemetery have not been met with action. ↩

-

Rainsford Island is part of the Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area, which designates it under the National Park Service. Its ownership extends to several other groups as part of the Boston Harbor Island Partnership, though public visits to the island are managed by the City of Boston in small, infrequent excursions, unlike other islands that see larger and more frequent traffic via ferries. ↩

-

Rebecca Greenfield, “Our First Public Parks: The Forgotten History of Cemeteries,” The Atlantic, March 16, 2011, link. ↩

-

See figure. ↩

-

Karla Rothstein, “The New Civic–Sacred: Designing for Life and Death in the Modern Metropolis,” Design Issues 34, no. 1 (2018): 33. The development of public parks stripped garden cemeteries of their multiplicity, reducing traffic to them and constraining their use to bereavement as they lost their allure as places of public recreation. Garden cemeteries have become, ironically, somewhat similar to cemetery islands: places far removed from cities, mostly frequented by those with the express purpose to be there. ↩

-

Burial grounds are located outside cities/settlements in several cultures, including Muslim, African, Chinese, and Indigenous. This is an abbreviated history and description of these cultures and their death practices for the purpose of comparison; each culture is much more nuanced. ↩

-

Most American garden cemeteries were established in the mid- to late eighteenth century. See Blanche M. G. Linden, Silent City on a Hill: Landscapes of Memory and Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1989). ↩

-

Nora Caplan, “Boston’s Other Housing Crisis: The Cemeteries,” Boston Magazine, April 11, 2019, link. ↩

-

Rothstein, “The New Civic–Sacred,” 29. ↩

-

Gus Fraser, Head of Preservation at Mount Auburn Cemetery, in discussion with the author, June 2021. ↩

-

Regina Harrison, Sales Manager at Mount Auburn Cemetery, in discussion with the author, June 2021. ↩

-

Rothstein, “The New Civic–Sacred,” 32. ↩

-

In some locales, such as the catacombs of Paris and puticuli of Ancient Rome, mass graves are commonplace and not necessarily the result of violence. ↩

-

W. J. Hennigan, “Inside New York City’s Mass Graveyard on Hart Island,” Time, November 18, 2020, link. ↩

-

Anna Lucente Sterling, “Public Access to Hart Island Resumes This Month,” NY1, May 5, 2021, link. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, burials increased to over 2,000 in 2020, from around 800 in 2019. ↩

-

John Freeman, “Hart Island’s Last Stand,” New York Times, July 16, 2021, link; and Melinda Hunt, founder of the Hart Island Project, in discussion with the author, January 14, 2023. The removal of the buildings on Hart Island was carried out in 2021 at an estimated cost of $52 million. The impetus for this removal was to open up more space for burial, eliminate the maintenance cost for the buildings, and do away with signifiers of a fraught past. ↩

-

Hunt, discussion. ↩

-

Maurice Chammah et al., “Inside Rikers Island, Through the Eyes of the People Who Live and Work There,” New York Magazine, June 28, 2015, link. Gradually throughout the twentieth century, inmates on Hart Island were transferred to Rikers. The demographics on Rikers Island can thus be used to inform those on Hart Island, where data is lacking. ↩

-

Freeman, “Hart Island’s Last Stand.” ↩

-

Doris J. James and Lauren E. Glaze, “Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates,” Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report, September 2006. ↩

-

Hunt, discussion. ↩

-

Hunt, discussion. ↩

-

Hunt, discussion. Hart Island was one of the first cemeteries to photograph the bodies of its dead as a form of documentation. The “lack of subterranean infrastructure” refers to the system’s lack of concrete foundations or individually dug graves. ↩

-

Hennigan, “Inside New York City’s Mass Graveyard on Hart Island.” Hennigan describes witnessing the burial process on Hart Island, particularly the use of plain wood caskets. ↩

-

Pavel Grabalov and Helena Nordh, “The Future of Urban Cemeteries as Public Spaces: Insights from Oslo and Copenhagen,” Planning Theory & Practice 23, no. 1 (2021): 81–98. ↩

-

Fraser, discussion. ↩

-

In New York State, about 160 cemeteries have been abandoned since 1990. Outside of individual maintenance efforts, these graves go unattended and are left to degrade. See Keshia Clukey, “Abandoned Cemeteries Slowly Dying,” Utica Observer-Dispatch, July 25, 2011, link. ↩

-

Christopher V. Maio, Rainsford Island Shoreline Evolution Study (RISES) (master’s thesis, University of Massachusetts Boston, 2009). ↩

-

Hennigan, “Inside New York City’s Mass Graveyard on Hart Island.” ↩

-

Hunt, discussion. ↩

-

Athanasios Nikolaidis, “What Is Significant in Modern Augmented Reality: A Systematic Analysis of Existing Reviews,” Journal of Imaging 8, no. (2022): 5. As augmented reality (AR) becomes more integrated into everyday devices and applications, its adoption may increase. AR features in social media apps or navigation tools could become more commonplace, altering the landscape of technology and necessitating new devices, among other possibilities. ↩

-

“Neglect,” here, translates to a digital memorial that ceases to receive visitors or views. ↩

-

“Technodystopia” here can be defined as a society that must relegate aspects of life to digital platforms as a result of failing physical infrastructure, overpopulation, and other threats. ↩

-

J. L. Drolet, “Transcending Death during Early Adulthood: Symbolic Immortality, Death Anxiety, and Purpose in Life,” Journal of Clinical Psychology 46, no. 2 (1990): 152. ↩

-

Drolet, “Transcending Death during Early Adulthood,” 152. ↩

-

Grabalov and Nordh, “The Future of Urban Cemeteries as Public Spaces,” 87. ↩

-

Grabalov and Nordh, “The Future of Urban Cemeteries as Public Spaces,” 88. ↩

-

Examples include the 9/11 Memorial Glade and Maya Lin’s Vietnam War Memorial, both of which use monolithic or contiguous forms to represent multiple people. ↩

-

McEvoy and Ray, Rainsford Island, 94. ↩

Jake Deluca is a recent graduate of Harvard's GSD where he received a master's in Landscape Architecture. His work explores landscape architecture as a medium of memory. He currently lives and works in Boston.