Prelude: A Sand Island Story

Nestled between Honolulu Harbor and Daniel K. Inouye Airport is a low-lying tract of land surrounded by turquoise shallows. Most know it as Sand Island, though the site has had many names, and taken many forms, over the last two hundred years. Today it is home to a wastewater treatment plant, a dirt bike track, a state recreational area, a junkyard, and a US Coast Guard base. Not many folks find reason to go there, but if you’ve ever flown over Oʻahu, you’d know it from above: outgoing transoceanic flights leave from the reef runway that sits perpendicular to the island, which stands out for its odd shape—not quite regular, but certainly not organic either.

In the early 1800s, the area of Sand Island was not what it is today, but instead mostly water and a collection of low-lying atolls linked by reefs and low-tide mudflats that made for excellent fishing. Kamokuakulikuli,1 the largest of the islets located there, was still a tiny thing—less than 5 square acres at high tide—and a nice place to rest for lunch if one was spending the day catching fish and octopus at the Kahololoa reef 2. You could walk to it easily at low tide if you left from the shore at Kahaohao, a fertile spot for taro cultivation. This was a time when Hawaiʻi’s land tenure system operated through communal stewardship, though, in 1840, Mōʻī Kamehameha III deeded the area, along with the fishing rights that made it such a prized location, to high chief William Keolaloa Kahānui Sumner. It would go on to change hands a couple of times in the ensuing decades, until, in 1869, the Hawaiian government chose Kamokuakulikuli as the site for a new quarantine station. Close to Honolulu and the deepwater channels of the harbor, but just far enough offshore to contain possible infection, the largest of the islets was renamed Quarantine Island, or Mauliola. Whenever areas of the surrounding reef or mudflats were dredged to make way for maritime industry, the material would be packed around Mauliola’s edges, and so the islet grew, from 5 acres to 28.3

In 1898, the United States unilaterally annexed Hawaiʻi and, among many pilfers, bought Quarantine Island for $1. Once Hawai‘i had been formalized into a territory, the US Army Corps of Engineers quickly set to work outfitting Honolulu Harbor for its military by deepening the ocean channels through a process called land reclamation. They piled the dredge onto Kahololoa reef, filling in the flats until Quarantine Island could hardly still be considered its own island. By the 1920s, it wasn’t, and by the 1930s, Sand Island materialized: 300 acres of terraformed coral and sand and seafloor in a prime waterfront location. The US War Department claimed 285.865 of those acres for its own on the grounds that it was the agency “through which the dry land was made.”4 That meant that only 12.3 acres belonged to the Territory of Hawaii. Sand Island, by those logics, was born federal.

By 1963, when the federal government turned the land over to the relatively young State of Hawaiʻi, Sand Island was a wasteland. Its mountains of trash burned so frequently and so violently that meetings were held about the budgetary stress it placed upon the Honolulu Fire Department.5 The Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR), which had recently taken up management of the area, set up patrols to curb the dumping, though they had little effect: Sand Island was already the habitual collection site for the refuse of urban Oʻahu.6 Individuals dumped their garbage there, and so did the county. In 1978, the Sand Island Wastewater Treatment Plan began operation as the largest in Hawaiʻi, turning the island into the terminus for the city’s shit. Besieged by trash, human waste, and noise pollution from jets landing on Honolulu Airport’s new reef runway, Sand Island had lost any semblance of its historic abundance. Then, quietly, when nobody was paying attention, a community settled among the refuse of a city that seemed to be forgetting its past.

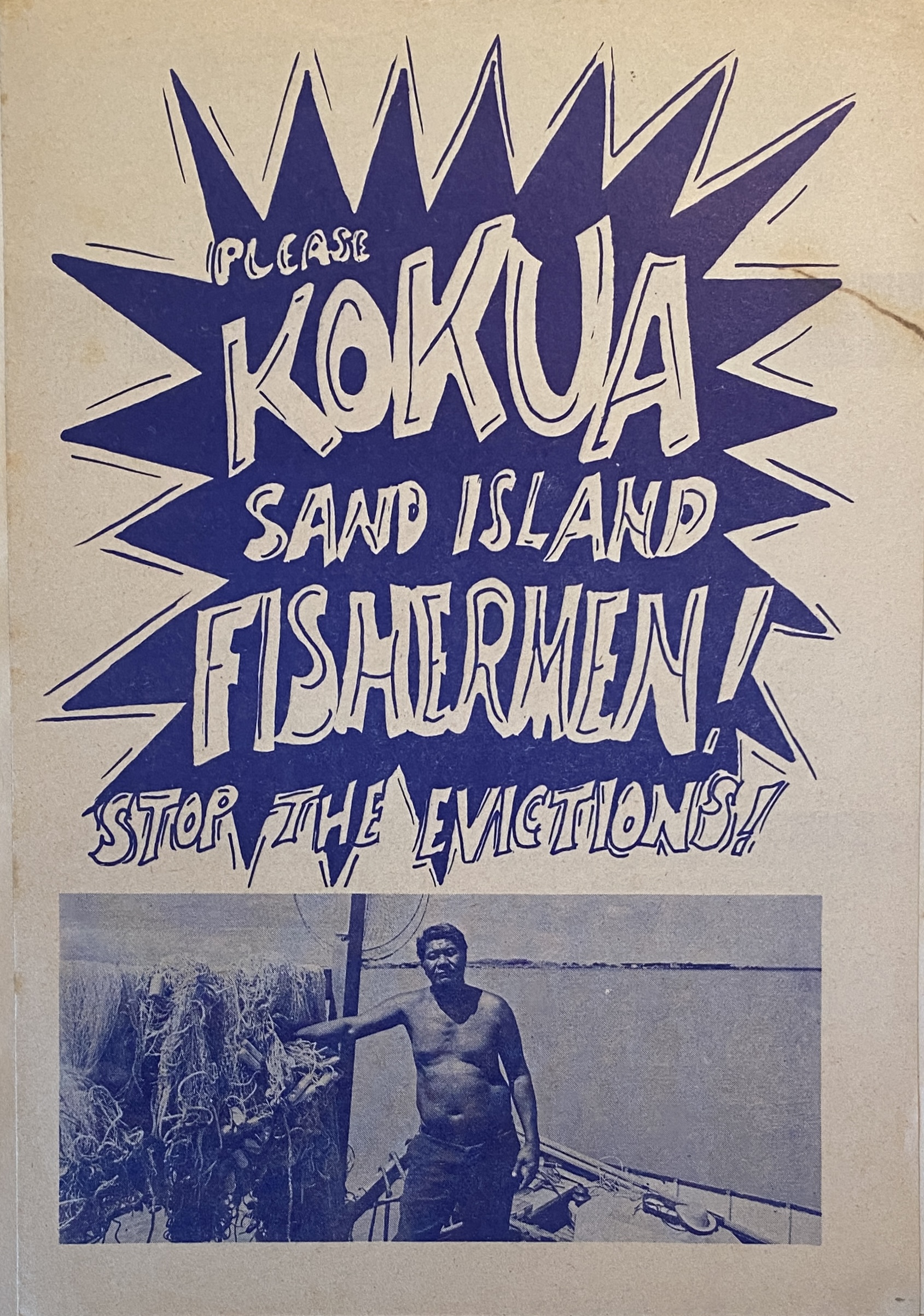

The state called them squatters, but most saw themselves as traditional fishermen who wanted to live a simple life.7 Many of them survived on limited and fixed incomes; some were veterans; a lot of them were Hawaiians; nearly all of them resented the city that loomed in the background of their waterfront enclave. One of the residents, Clement Apollo, put it plainly in a 1979 documentary interview: “You can’t be free out there,” he said as he gestured to the urban density beyond.8 Apollo was one of many residents interviewed by the filmmaker Victoria Keith, who documented their eviction and the bulldozing of their homes to make way for a long-anticipated state recreational facility the winter of that year. The Sand Island residents, seeing themselves as practitioners of the “old ways” of Hawaiian life, offered to remain in the park as public educators.9 After all, Mokauea, one of the offshore islets spared from twentieth-century dredging, had recently won a sixty-five-year lease from the state, which would allow them to continue their existence as a traditional fishing village. The state, however, denied the Sand Island residents’ petition on the grounds that they could not prove historical tenancy on “reclaimed land.” Sand Island couldn’t be returned to Hawaiians, the reasoning went, if it hadn’t been Hawaiʻi in the first place.

Reclamation Imperialism

“Land reclamation” is the term used to describe the process of “creat[ing] new land from the sea.”10 Often, this entails dredging the seafloor and piling it up somewhere else, with the goal of developing that fresh landform or deepening water channels (or both). While human societies have engaged in versions of this for hundreds of years, the practice of land reclamation has recently taken on fresh political dimensions as questions of territorial sovereignty and global real estate speculation collide in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Large-scale dredging projects have become common, birthing new landmasses across the globe. This is the type of land reclamation I’m interested in thinking about here, though the broader term is slightly more capacious: it can also describe the remediation of land degraded by industrial activity such as mining operations.11 In some instances, the reclaimed land can be lucratively developed; in others, it is intentionally “wastelanded,” as scholar Traci Brynne Voyles calls it.12 Sand Island falls into the latter category. These two facets of land reclamation, though different, are importantly tethered by questions of ownership: Does an entitlement to profit include an obligation toward care? What economic and ecological debts are set into motion when fresh lands are brought to the surface?

One particularly salient contemporary example of reclamation imperialism—a term I want to speculatively offer here—is the case of Panganiban Reef, more commonly known as Mischief Reef, located in the South China Sea. Panganiban Reef is one of more than 100 small islands that comprise the Kalayaan Island Group (also called the Spratly Islands), an archipelago that is claimed by China, Taiwan, Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines.13 In 2015, China began a land reclamation project of unprecedented scale, dredging enormous quantities of sand to create land masses large enough to support military outposts along this important shipping corridor.14 The physical characteristics of the reef system are important here, since they determine what economic and political rights can be claimed: economic zones afforded by landmasses above a high-water mark hinge upon their ability to “sustain human habitation and economic life of their own.”15 Those that cannot, considered mere “rocks,” generate entitlement to at least 12 nautical miles; those that can are entitled to exclusive economic zones of 200 nautical miles. While legally China is not able to claim an exclusive economic zone within territory formally belonging to the Philippines, its establishment of airstrips, harbors, and other defense infrastructures succeeds in establishing what journalists call “facts on the ground” control over the area.16 If you’ve managed to conjure an island military base from the sea, it is easy to be impervious to others’ territorial claims. Reclamation imperialism has enabled and entitled China to operate an outpost off a reef that international courts have ruled is not under their jurisdiction.

The military and economic promises of reclaimed land have also given birth to artificial islands as speculative real estate, the most iconic of which are Dubai’s “Palm Islands” and the United Arab Emirates’ “The World” archipelago, which both began construction in the early 2000s.17 Funded by the petrochemical industry and constructed out of sand dredged from the floor of the Persian Gulf, these “land reclamation” projects have added hundreds of miles of lucrative beachfront real estate that are more architectural than natural in their function and form: new land primed for mansions, luxury resorts, and shopping centers. The geographers Mark Jackson and Veronica della Dora suggest that the construction of these artificial islands offers glimpses into the existential anxieties of the wealthy, in that they promise exclusivity and respite from the environmental precarity and inequity wrought by global capitalism, even if that promise is contingent and tenuous.18 None of us are exempt from the crisis, even if we are not equal contributors to it, and the oceans don’t care how valuable the real estate might be.

Since learning the term “land reclamation,” I have been meditating on the juridical premise it aims to describe, finding that the prefix seems to do a lot of aspirational work for the claimant. Who, I wonder, owns the seafloor, and how is it acquired? What forms of property-making transpire through the process of land reclamation, and to whose benefit? The geographer Martin J. Haigh, in writing about the ethics of reclaimed land, describes it as a technological product—an artifact—and this has consequences for how it is legislated: it is, he writes, “not ‘nature.’”19 Put another way, reclaimed land awkwardly straddles the legal difference between real property (land) and personal property (things), or at least creates space for bureaucratic and proprietary malleability.20 In the example of the Boeung Kak Lake project in Phnom Penh, which saw the filling of a lake for the purposes of high-end real estate development, the geographer Erin Collins shows how land reclamation processes effected the displacement of the urban poor who had, until then, lived at the swampy edges of the water. “Civil engineering, it turned out, made for excellent social engineering,” they write, explaining how filling the lake allowed the area to be redesignated as state public land and, in turn, its inhabitants as “squatters” (not unlike the similarly fated residents of Sand Island).21 In creating fresh surfaces above the high-water mark, then, the colonial state “shores up” once-murky spaces into dryland oases more conducive to biopolitical and economic management.

Submergence/Emergence

As sea level rise imperils low-lying communities across the Pacific, India, the Gulf Coast, Asia, and beyond, many are growing increasingly anxious about the shifting boundary between surface and sea. Often, these concerns cohere around the vulnerability of human and nonhuman life, though geopolitical disputes over territorial control also reveal some of the more capitalistic contours of concern. As the long shadow of land-as-property casts itself across the lived realities of land-as-relation, who, or what, I wonder, is deemed expendable when “value” erodes with the tides?

Climate experts often describe Oceania and its people as living on the front lines of climate change, estimating that many of the low-lying coral atolls of the Pacific may become uninhabitable by 2030 (or, at the time of this writing, in less than seven years).22 Several islands, including some within the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, and Kiribati, have already slipped underwater; lands that haven’t yet succumbed to the sea are struggling to grow crops in salinized soils, dangerously diminishing the capacity to sustain the communities who live there. As one Tuvaluan explained in plain terms to a reporter in 2019, “The sea is eating all the sand.”23 One recent study, focused on the Republic of the Marshall Islands, suggested that relocation is the “best choice” for islanders, though Indigenous voices from within these nations have argued for the importance of staying.24 Land reclamation offers a promising technique to stabilize the islands by “armoring” atolls against sea level rise.25 For some, this may be the difference between staying and leaving.

While such proposals to engage ocean dredging emerge from an important commitment to Indigenous homelands, they bring a suite of complicated collateral impacts that range from environmental to political. As Chuukese scholar Angela L. Robinson explains, “dredging impacts the entire ecology of marine life, and for a peoples depended on the ocean, it’s simply catastrophic.”26 Further, the cost, equipment, and labor for such an undertaking are often (dangerously and imperially) circumscribed by a reliance upon external funding by multilateral institutions and through foreign investments to support the large-scale engineering work that it takes to “shore up” the islands.27 And so, on the one hand, land reclamation opens up possibilities to realize Pacific Islander futures at home; on the other, the speculative potentials of reclaiming land also embolden the entities that fund and execute the dredging, such that residents should be reasonably wary of being rendered “squatters” in the process.

Refusal to capitulate to the fact of climate crisis is then as much about securing rights to space as it is about maintaining relationships to place: when homeland slips undersea, and seafloor extends the surface of home, the acquisitive underpinnings of imperial expansion reveal themselves anew, still vibrant and at the ready. The island now known as Wake, for example, is currently embroiled in disputes over jurisdiction, claimed by both the United States and the Republic of the Marshall Islands. In describing these competing claims, human rights lawyer Julian Aguon notes that neither is correct: “The strongest claim is that of the Marshallese people themselves, who say the island is theirs by way of its history, culture, and birthright, and who long to be able to take proper care of it.”28 When Aguon explains that, “if my corner of the Earth had an anthem, it’d be this: To hell with drowning,” he is not thinking of the military installations that have made the atoll such a valuable geopolitical asset; he is thinking of stories about the places we love and the important role they play in keeping us—and by extension ourselves—alive.

Conclusion: A Sand Island Future

The last time I visited Sand Island, just a few months ago, the sea was swelling on the rocky southeastern end where the State Recreational Facility entrance sits. As I walked north along the shore, however, the protection of the harbor calmed the water into a still, milky aqua. Thorny keawe bushes offered little shade from the summer sun, but gave just enough to some folks who had set up camp and were living there, relatively undisturbed by the crowded city just beyond. A few have built shacks on the breakwater; one woman dove straight into the cool, clear water from her doorstep. In a photograph, it looks idyllic, but when the wind blows in their direction, the stink from the wastewater treatment facility hangs in the air. Regardless of the breeze, the jets taking off on the reef runway blare overhead. Though the Department of Land and Natural Resources usually prohibits the practice of shoreline armoring, Sand Island’s function as the terminus for Honolulu’s sewage saves it from being swallowed up by the sea: large concrete armaments currently work to hold the artificial island in place.29 Were it not for this, would Sand Island be left to the mercy of the tides? I wonder. “To hell with drowning” is, perhaps, another way of saying to your homeland that, if it comes to it, “I will drown with you.”

-

This name roughly translates to “the Ākulikuli plant island.” ↩

-

This name roughly translates to “the Long reef.” ↩

-

The historical details in this paragraph are drawn from “Sand Island,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, February 15, 1964, 13, and E. H. Bryan Jr., “Sand Island ‘Grew Up’ from Tiny Quarantine Station Site,” Honolulu Advertiser, January 22, 1956, A8. ↩

-

Bryan, “Sand Island ‘Grew Up’ from Tiny Quarantine Station Site,” A8. ↩

-

“Sand Island Brush Fires Increase, Officials Report,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, June 23, 1964, 10. ↩

-

“State to Clean Up Sand Island Mess,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, September 24, 1964, 9. ↩

-

For more about the Sand Island community and the circumstances of their eviction, see Victoria Keith, director, The Sand Island Story, Victoria Keith Productions, 1981. ↩

-

Sand Island Dubs 1–2, 4–7, ʻUluʻulu, the Henry Kuʻualoha Giugni Moving Image Archive of Hawaiʻi, University of Hawaiʻi—West Oʻahu, 19.07. ↩

-

For more on the cultural park, see Stanley A. Mofjeld, “Sand Island Cultural Educational Park: An Alternative to the Removal of the Existing Community,” MA diss., University of Hawaiʻi, 1979. ↩

-

J. L. Stauber, A. Chariton, and S. Apte, “Global Change,” in Marine Ecotoxicology: Current Knowledge and Future Issues, ed. Julian Blasco (London: Elsevier, 2016), 273–313. ↩

-

Martin J. Haigh, “The Aims of Land Reclamation,” in Reclaimed Land: Erosion Control, Soils and Ecology, ed. Martin J. Haigh (Rotterdam: A.A. Balkema, 2000), 1–20. ↩

-

Traci Brynne Voyles, Wastelanding: Legacies of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015). ↩

-

For a good overview of territorial claims across the archipelagoes in the South China Sea, see Francisco A. Magno, “Environmental Security in the South China Sea,” Security Dialogue 28, no. 1 (1997): 97–112. Since 1985, Brunei has implicitly claimed a continental shelf that overlaps the Louisa reef. See “Spratly Islands,” CIA, World Factbook website. For a detailed discussion of claims to the Spratlys in light of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, see Sondra Faccio, “ ‘Human Habitation of Economic Life of Their Own’: The Definition of Features between History, Technology, and the Law,” Liverpool Law Review 42 (2021): 15–33. ↩

-

Editorial Board, “Chinese Mischief at Mischief Reef,” New York Times, April 11, 2015. ↩

-

UN General Assembly, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (December 10, 1982), 66. ↩

-

David E. Sanger and Rick Gladstone, “Piling Sand in a Disputed Sea, China Literally Gains Ground,” New York Times, April 9, 2015. In 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague determined that the reefs claimed by China sat within the exclusive economic zone of the Philippines, citing the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. The Hague, “The South China Sea Arbitration,” press release, 2, link. ↩

-

Mark Jackson and Veronica della Dora, “ ‘Dreams So Big Only the Sea Can Hold Them’: Man-Made Islands as Anxious Spaces, Cultural Icons, and Travelling Visions,” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 41, no. 9 (2009): 2086–2104. ↩

-

Jackson and Della Dora, “Dreams So Big Only the Sea Can Hold Them,” 2091. ↩

-

Haigh, “The Aims of Land Reclamation,” 1. ↩

-

For an excellent example of how this malleability might be put to use, see Erin Collins’s analysis of the Boeung Kak Lake project in Phnom Penh, which used “the material transformation of water into land” to reclassify the area into state private land. Erin Collins, “Reclamation, Displacement and Resiliency in Phnom Penh,” in Other Geographies: The Influence of Michael Watts, eds. Sharad Chari et al. (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2017). ↩

-

Collins, “Reclamation, Displacement and Resiliency in Phnom Penh,” 199. ↩

-

Curt D. Storlazzi et al., “Most Atolls Will Be Uninhabitable by the Mid-21st Century Because of Sea-Level Rise Exacerbating Wave-Driven Flooding,” Science Advances 4, no. 4 (2018): 3. ↩

-

Eleanor Ainge Roy, “‘One Day We’ll Disappear’: Tuvalu’s Sinking Islands,” The Guardian, May 16, 2019, link. ↩

-

Mikiyasu Nakayama et al., “Alternatives for the Marshall Islands to Cope with the Anticipated Sea Level Rise by Climate Change,” Journal of Disaster Research 17, no. 3 (2022): 315–26; Carol Farbotko, “Wishful Sinking: Disappearing Islands, Climate Refugees, and Cosmopolitan Experimentation,” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 51, no. 1 (2010): 47–60. ↩

-

“Armoring” is the term used in Virginie K. E. Duvat and Alexandre K. Magnan, “Rapid Human-Driven Undermining of Atoll Island Capacity to Adjust to Ocean Climate-Related Pressures,” Scientific Reports 9, 15129 (2019). ↩

-

Angela L. Robinson, “Colonial Climates: Indigenous Futures beyond the Human,” lecture, University of Washington, Seattle, January 12, 2022. ↩

-

Liam Saddington, “The Chronopolitics of Climate Change Adaptation,” Territory, Politics, Governance 11 (2023): 1–20. ↩

-

Julian Aguon, “To Hell with Drowning,” The Atlantic, November 1, 2021, link. ↩

-

Teresa Dawson, “Board Talk: Erosion, Sea Level Rise Threaten Sand Island Wastewater Plant Outfall,” Environment Hawaiʻi Newsletter, August 31, 2019. For an important critique of the political exceptions made for shoreline armoring, see Judy Rohrer, “Imperial Dis-ease: Trump’s Border Wall, Obama’s Sea Wall, and Settler Colonial Failure,” American Quarterly 74, no. 3 (2022): 737–63. ↩

Hiʻilei Julia Kawehipuaakahaopulani Hobart is an Assistant Professor of Native and Indigenous Studies in the Program in Ethnicity, Race, and Migration at Yale University. She is currently working on a project about the Hawaiʻi State Parks system and Kanaka Maoli dispossession.