Around the Perimeter/Looking for the Present

It takes me three hours to walk nearly 6 miles around the Chevron El Segundo Refinery. Just south of Los Angeles International Airport, the refinery spans one thousand acres between the beach cities of El Segundo and Manhattan Beach in Los Angeles County, facing Santa Monica Bay to the west, and following along State Route 1—the iconic Pacific Coast Highway—on the east. My walk last March around the perimeter of the refinery might have taken less time were it not limited by intermittent pedestrian access—sidewalks beginning and ending without warning, stranded bus stops, and a detour around the northwest corner, which was entirely inaccessible—and if the nearby ocean didn’t beckon me to take a dip.

To be a body walking the perimeter of this petrochemical infrastructure is to encounter a city—a fortress, really—within a city. Beyond its explicit function as a refiner of petrochemicals, Chevron also runs its own power plant, fire department, water treatment plant, laboratory, clinic, shops, cafeteria, credit union, training facilities, fitness center, park, and playground. And yet, none of this is visible from the perimeter, nor in publicly available archives. Instead, the public sees only glimpses of monolithic industrial equipment, otherwise shielded and obscured behind the reflective glass of corporate architecture; sterilized corporate-sponsored municipal signage; and massive artificial berms.

Tovaangar, or what is currently called the greater Los Angeles Basin, is the US settler colony’s largest urban oil field. With a third of Angelenos living near an active or idle drill site,1 and with more than 350,000 people living within 600 feet of an unplugged oil or gas well,2 this petrochemical landscape, and our proximity to it, has been intentionally hidden in plain sight. This was not always the case, as Tongva and Chumash communities have lived in relation to tar pits for millennia, and the growth of successive settler colonies (Spanish, Mexican, and US) were visibly and economically reliant on the so-called discoveries of fossil fuel deposits.3 However, looking for wells, pumpjacks, pipelines, and refineries in the present requires spotting architectures of camouflage and asking, well, camouflaged by whom, and against whom? As the heyday of California oil has receded, and as burgeoning intersections of environmental justice movements fought for the phaseout of drilling where communities live and work, these persistent petrochemical infrastructures have, in some cases, survived through lobbying and intimidation, and, in others, by embedding themselves more deeply into the urban fabric.4 Insofar as the Chevron Corporation—which was famously and successfully sued for environmental catastrophe in Lago Agrio, Ecuador, for $9.5 billion5—constitutes a vast global petrochemical structure that enables not only contamination and exploitation but also US-backed war crimes, as in occupied Palestine, it is useful as a counterpoint to understand how, through its refinery in El Segundo, Chevron employs these tactics against people and planet in the second-largest metropolitan area in the US.6

Wells—mile-deep puncture wounds in the land—have existed and do exist in El Segundo, and Chevron itself currently operates 26,243 unplugged wells across California (8,886 of which are idle), the most of any California operator.7 The corporation is also the highest spender in the state on pro-oil lobbying efforts.8 But the refinery I am walking around is a true petropolis—a central node in California’s petroleum industrial complex, with vast expanses full of tanks, pipes, and rails. Despite how policies and plans governing (and thus, shaping popular understandings of) zones of habitation and extraction tend to see these sites as contained, Neeraj Bhatia reminds us that sites like El Segundo are instead highly networked: “What [these policies and plans] tend to ignore is the interdependent relationships between these zones, enabled by logistical infrastructures, and characteristic of understanding capitalism as a form of world ecology.”9 Here, the refinery, as logistical infrastructure, operates as a series of containers and conduits on a vast surface surrounded by neighborhoods—thus touching communities, homes, livelihoods, and lives.

On its website for the El Segundo refinery, Chevron shares the following reflection on this adjacency by way of introduction:

In the beach communities just south of Los Angeles International Airport, you will find homes, plenty of recreational activities, and lots of friendly people. You probably wouldn’t expect to find the largest refinery on the West Coast, but you will. Can a major oil refinery really be a good neighbor in an environment like this? Chevron’s El Segundo Refinery has strived to do so for more than a century and we are proud of our record of contributions and results.10

I take their question, “Can a major oil refinery really be a good neighbor?” as an invitation to look—to go and see for myself. Built environment practitioners have myriad tools of discernment at our disposal, ranging from high-resolution satellite images to three-dimensional GPS-located datasets to integrated modeling systems, but none take the place of the site visit—of verifying existing conditions in the field. In other words, before, after, and in spite of any drawings we create, we are bodies looking, traversing, and thus discerning and proposing which past, present, and future “existing conditions” in which “fields” must be seen, understood, and transformed.

Main Street in the city of El Segundo runs southward and terminates at the refinery’s northernmost edge. This is where I start my trek, at a grassy slope in the northwest corner, off El Segundo Boulevard, by a large sign marking Chevron’s habitat for the endemic El Segundo Blue Butterfly (Euphilotes battoides allyni). The preserve, the sign boasts, maintained and monitored by the Chevron El Segundo Refinery, is “one of two sites in the world that provides sanctuary to the endangered El Segundo Blue Butterfly.” The other site is located between Los Angeles Airport (LAX) and the Pacific Ocean, on the remains of Surfridge, an abandoned wealthy seaside neighborhood. It is notable that nearby refineries of similar size and scale (Marathon Los Angeles, Valero Wilmington) have no such pretense of environmental stewardship, and it is not coincidental that those refineries abut communities that are less affluent and less white. Being a “good neighbor,” in Chevron El Segundo’s case, apparently only extends to its nonhuman ecological neighbors, employing greenwashing tactics to virtue signal to its human ones.

Heading east, I arrive at the administration building, located between a laboratory, a clinic, and a shipping entrance, which suggests a corporate campus to the south. There is a generous, clean one-way driveway with manicured lawns, outdoor seating, visitor parking, and assorted flags (for the US, California, and occasionally, a rainbow flag for Pride Month). This edge of the refinery faces its municipal neighbors to the north: light industrial, commercial, and residential buildings, including restaurants, bike rental shops, and bars. But the sidewalk ends abruptly at Gate 2, forcing me to cross the street to the city side in order to continue walking east. It’s only after five or six blocks that I start to glimpse the first towering steel structures that comprise the low-sulfur fuel oil (LSFO) complex with its light green tanks between brick walls and eucalyptus stands.

At the eastern end of the refinery’s north edge, past Gates 3–9, I walk into Chevron Park, a private open green space for El Segundo Refinery’s one thousand employees and their families. Attempting to take a look around, I am greeted by a curious security guard who asks if I am lost. I nod and turn around. Just past the park, a McDonald’s and a Chevron gas station nestle into the corner of the Pacific Coast Highway and El Segundo Boulevard. Across the street, at the northeast corner, are more sloped berms. These ones, however, are not providing protection to the El Segundo Blue Butterfly but sheltering Raytheon’s campus farther east.11 There are hardly any pedestrians on the meager dirt path along the Pacific Coast Highway, which, at this point, is intended to move vehicular traffic quickly through the corporate and commercial space that flanks it. Opposite shopping centers, a café, a Whole Foods, and a golf center across the road, more huge berms rise 15 feet above street level (and are about 50 feet wide), obstructing my view of the reservoirs in the refinery’s interior. Halfway between the northeast and southeast corners of the refinery, chain-link fencing gives way to an archway over a rail track, with custom letters reading “CHEVRON EL SEGUNDO,” with the eye of a security camera looking back at me. This rail spur carries petroleum products across the PCH, usually at night when traffic is lighter. Gasoline is taken to terminals, where trucks pick it up to redistribute to local gas stations (LAX, on the other hand, receives jet fuel directly from pipelines). I find out later from a Chevron representative that excess fill from the construction of Interstate 105, completed in 1993, was used to build these berms up to their current height.

But it is on the south side, adjacent to the residential City of Manhattan Beach, that I have the most difficulty on my walk. Rosecrans Avenue is wide, and I find myself teetering on the curb most of the way west, with sand and bushy overgrowth underfoot. Occasionally, a square of concrete emerges to host a rounded bench for the Beach Cities Transit (BCT) Line 109 route. But otherwise, the street is flanked by some of the largest and most forested berms I’ve encountered on my walk, measuring between 60 and 80 feet wide and 15 feet tall. In fact, there is almost nothing to be seen by the refinery’s more affluent and politically powerful Manhattan Beach neighbors, nor heard, as it is along this edge that Chevron operates its “noise monitoring program.”12 Although Manhattan Beach shares its entire northern border directly with the El Segundo refinery, its Code of Ordinances dictates that “the operation or maintenance of any refinery, plant or factory for refining or converting crude oil or petroleum into gasoline, distillate, kerosene, naphtha, benzine or any other refined product by any means whatsoever in the City is hereby declared to be a nuisance, unlawful and prohibitive.”13 And although it does not quite reach me or would-be bus riders on the almost-sidewalk, there is a certain cruelty in the abundance of shade provided on the edge of a refinery, in a metropolitan area notorious for heat inequities due to oil-fueled climate chaos.

Curiously, despite the refinery’s historical and narrative ties to the City of El Segundo, many of its neighbors are actually residents of Manhattan Beach. The neighborhood of El Porto in Manhattan Beach backs up against the refinery and another berm, roughly 10 feet tall. Chevron employees park along this edge in reserved parking spots, and above, light green metal sheds monitor smells by sending out lasers along the boundary to detect which stray chemical compounds might waft outward. While these physical and digital technologies—employed to render the refinery’s operations imperceptible—are presented as the actions of a good and harmless neighbor, I sense an eeriness to our resulting inability to look back into the refinery, to detect what our neighbor is up to behind their property line.

On the actual sands of Manhattan Beach, surfers and swimmers stake out waves, families share food under umbrellas and atop blankets, runners and bikers flow along pathways—and crude oil tanks measuring 250 feet across, painted moss and seaglass green, tower behind rows of beachfront residences, while oil tankers wait offshore to transfer crude to the smaller ships that navigate to Chevron’s pier. A friend tells me they took swimming lessons growing up around here and remembered those cylindrical green giants. Fog rolls through often. Walking northward along Vista Del Mar, the marine terminal comes only slightly into view, and my mind easily takes in the lushness of the coast and imagines it continuing inland—which is, of course, not the case. There is another Chevron gas station at the corner.

The primary vegetation on the public-facing side of all these berms is primarily introduced ornamentals: Trailing African daisy (Dimorphotheca fruticosa), Chilean sea fig (Carpobrotus chilensis), South African sea fig (Carpobrotus edulis), Trailing treasure flower (Gazania rigens), Indian hawthorn (Rhaphiolepis indica). I spot rogue nasturtiums (Tropaeolum majus) here and there. But the berms’ refinery-facing side, which we cannot see from the street, is virtually all barren sand dune, locked into place with asphalt—itself a by-product of crude.

I am only afforded this view on the one day a year that the interior of the El Segundo Refinery is open to the public. In November 2023, on the refinery’s “annual community day,” I take a guided bus tour that departs from the employees’ park, where a pop-up fair offers family-friendly displays and refreshments. The public must register for this event, and our IDs are checked at the entry point. No other area of the refinery is accessible to the public, and certainly not on any other day. I am a permissible body among other permissible bodies, sitting and viewing the refinery from within an air-conditioned vehicle, where we are instructed not to take photos. I was unprepared for how it would feel to see so much sand frozen beneath cracked, caked gray coating, like ice cream dipped in chocolate. “Otherwise, the dunes want to keep moving around,” our tour guide offered as explanation, adding that teams of mules were used originally to discipline the dunes. I remember with a dull and hollow sense of loss that, on the street side, both sand and ornamental plantings spill freely and exuberantly out of the chain-link fencing. With wind, water, and life, the dunes want to move around.

Since time immemorial, these dunes and plains between the Gabrieleno/Tongva villages, Waachnga and 'Ongoova'nga,14 have been nourished by the 385-square-mile Santa Monica Bay Watershed, which stretches across 55 miles of coastline from Malibu to San Pedro. In the Los Angeles Basin, as elsewhere, water and the life that depends upon it continue to exist and move in relation to one another, in spite of anthropogenic dams, caps, diversions, and introduced toxins. In addition to immobilizing these living dunes, thus disrupting existing flows of water and life and creating new challenges through those disruptions, Chevron operates its own effluent treatment plant (ETP). As we drive past the ETP, our tour guide cheerfully explains that the refinery treats or “cleans” its own industrial wastewater (and all the rainwater that collects on its site) before discharging it 2 miles offshore into Santa Monica Bay. But how can all the flows of water possibly be contained within one thousand acres, treated, and safely returned to their many cycles? On the tour bus, we are told that this refinery has been recognized nationally as the “safest” refinery—twice. Meanwhile, a study of eighty-one oil refineries nationwide ranked Chevron El Segundo as the largest water polluter for nitrogen and selenium in 2021, noting that these refining by-products are in fact being legally discharged into the Pacific Ocean.15

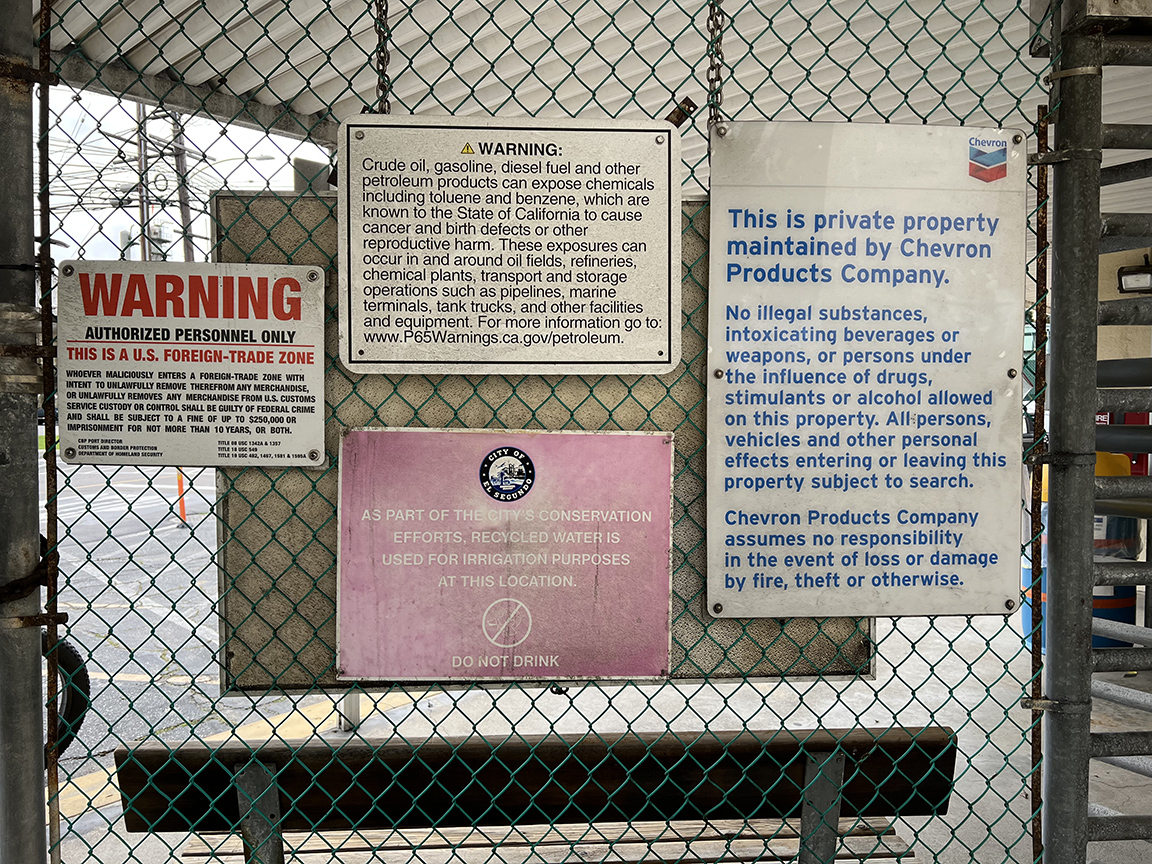

However friendly a neighbor the refinery would like to imagine itself, it cannot help but tell us who it really is through legally mandated signs, which, more often than not, hazard a different kind of neighbor. There are easily over a hundred signs, clustered around specific entrances (Gates 2–38); some are spaced evenly along chain-link fencing, brick walls, and underground pipelines; some are freestanding, announcing the presence of endangered species or employee parking; and some, like the ones opposite the administration building, proudly sponsor “Downtown El Segundo” in plaques embedded in masonry. The signs come in different sizes, shapes, fonts, and colors, specified by corporations (Chevron Products Company, South California Gas Company, Plains Marketing, L.P.) and government agencies (City of El Segundo, El Segundo Police Department, State of California, and US Customs and Border Protection). I count at least a half dozen distinct phone numbers to call for urgent responses to emergencies, penal codes at municipal and federal levels, and the word “WARNING” in regard to everything from trespassing to known carcinogens to water quality safety. As these many invisible forces of policing and border security coil and tangle with one another at these boundaries, it is hard to imagine how any individual could productively navigate a hypothetical emergency, much less the safety of their own body, as they encounter them.

From Above/Looking for the Past

Viewing the refinery from above—in our case, now, via satellite images—brings into focus the scale of alienation created by infrastructures of extraction. All along each edge of the refinery, adjacent communities encounter a purportedly unknowable expanse whose scale defies easy understanding—a crude-oil tank with a 250-foot diameter is five times the width of nearby residential parcels. Even though we logically know that the sounds, smells, impacts of pollution cannot be contained (especially in less affluent, less white communities, where there is barely an attempt to do so), residents, tourists, consumers, and nonhuman beings are presented a false reality of our world—gaslit by the material image Chevron stages on the ground. A 6-mile walk along a perimeter is but a dashed and dotted line to 1,000 impenetrable acres. Like line drawing, tracing this edge ignites possibilities for understanding the negative space of what we have not been allowed to see.

From above, we can look for (and find) the past—that is, what Cruz Garcia, Nathalie Frankowski, and others call colonial footprints, the visual continuities of settler colonization and white supremacy. Garcia and Frankowski write of the university and the prison as two institutions that comprise “part of the colonial footprint of cities and suburbia that are material displays of ideology and wealth accumulation via land occupation.”16 We might understand the refinery in the same vein. This specific refinery and its accompanying city were both manifested by Standard Oil—El Segundo referring literally to the company’s second refinery after Standard’s first in Richmond, California (built in 1902). The boundaries of the refinery still follow and reveal an older road network, that of the Spanish and Mexican colonial rancho system. Rancho Sausal Redondo, a 22,458-acre land grant awarded to Antonio Ygnacio Ávila in 1837, covers an area that currently also includes Playa Del Rey, Manhattan Beach, Lawndale, Hermosa Beach, Inglewood, Hawthorne, and Redondo Beach.

Standard Oil purchased the land from Anglo-American settlers John S. Vosburg and Anna S. Vosburg in 1911 for $10 (about $300 today).17 It established the adjacent city of El Segundo, incorporated six years later, in 1917, as a “black gold suburb”18—an exclusively white company town. In fact, oil, like gold before it, was meant to be a white man’s industry, and like gold prospectors before them, oilmen employed both legal and extralegal means to racially exclude. As one example, according to the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation’s own metrics, proximity to oil industries should have warranted an immediate red designation. However, while this was the case for Black and Brown neighborhoods, the historian Daniel G. Cumming writes that in El Segundo, where oil wells, refineries, and tank farms were all “derogatory influences,” redlining was “ruled out,” because residents wanted to protect their properties against “racial hazards.”19 In 2010, El Segundo was still 78 percent white, and based on Chevron’s own records of its pensioners, a significant majority of Chevron oil workers at all levels continue to retire in El Segundo, which makes sense, given that Standard Oil/Chevron has contributed enormously and continuously to the city, its library, its schools, its fire stations, its port, and numerous other amenities in order to keep its company town white. Compared to newer refineries in the nearby Gateway cities of Southeast Los Angeles, the presence of these amenities both in the City of El Segundo and within the Chevron El Segundo Refinery itself clues us into this history embedded in infrastructure.

Over time, a revolving door of industry, real estate development, and government has shaped this petrochemical beach city that unironically hosts (and fuels) the nation’s largest weapons manufacturers (Northrop Grumman, Boeing, Raytheon, and Lockheed Martin), the Los Angeles Air Force Base and the US Space Force’s Space Systems Command, the toy manufacturer Mattel, the Los Angeles Times, and the Hyperion water reclamation plant—all while its own Recreation & Parks Department served as the inspiration for the 2000s sitcom Parks and Recreation. The capital investments made and resources provided by Chevron and other oil companies—besides fuel, a network of railways, fire stations, piers, and electrical lines—attracted aerospace, military, and technology companies and spurred real estate speculation. For instance, between the years 1925 and 1930, the city’s land values increased 1309 percent, more than any other city in Los Angeles County.20 Whereas in the early first half of the twentieth century, the El Segundo Land and Improvement Company, which was not technically affiliated with Standard Oil of California yet included them on their board, purchased 1,460 acres adjacent to the refinery for the initial development of the town,21 the latter half of the century saw the Chevron Land and Development Company redeveloping its own degraded brownfield land into a luxury shopping center, Manhattan Village, in 1982. Even when the oil is gone from the land, extraction continues.

From above, the scale of the petrochemical empire’s conduits—the railways, airways, and seaways—too, comes into focus. However dislocated the refinery can be from its immediate environs, it is a critical point in a global network of fossil fuel. Even more so than the upstream oil wells and fields, refineries anchor themselves through their midstream flexibility and adaptability, aggregating crude oil from all corners of the earth. However, the environmental justice organizations Stand.earth and Amazon Watch have reported that half of all oil drilled and exported from the Amazon comes directly here, to what is currently called the state of California. Of that amount, half is processed by just three refineries within the Greater Los Angeles area: Chevron El Segundo, Marathon Los Angeles, and Valero Wilmington.22 The report further details LAX as the top global airport consumer of jet fuel (much of which is provided directly by Chevron El Segundo), which comes from the Amazon rainforest as well.23 Across the globe, since 2020, Chevron has had a 39.66 percent owned and operated interest in the Leviathan gas field, Israel’s largest energy project, and a 25 percent owned and operated interest in the Tamar gas field. Together, Leviathan and Tamar supply 70 percent of electricity in the settler state.24 Insofar as both oil and capital transcend oceans and political borders, our understandings of neighbors and of front lines must shift as well.

It is no wonder that Edward Soja said of Los Angeles, “What better place can there be to illustrate and synthesize the dynamics of capitalist spatialization?”25 And, speaking nearly three decades later about extraction zones across the Americas, Macarena Gómez-Barris reflects that it is precisely “by making visible microspaces of interaction and encounter within geographies where coloniality has left and continues to leave a deep imprint” that we might indeed show “how renewed perception offers a method for decolonized study.”26 Here, Garcia and Frankowski assist us in finding the through line: “While Modernism’s abstractions erase modernity’s colonial footprints, the role of emancipatory practices consists in bringing the legacy of modernity’s systematic, global-scale subjugation and spoliation back into resolution.”27

Across Time/Looking for the Future

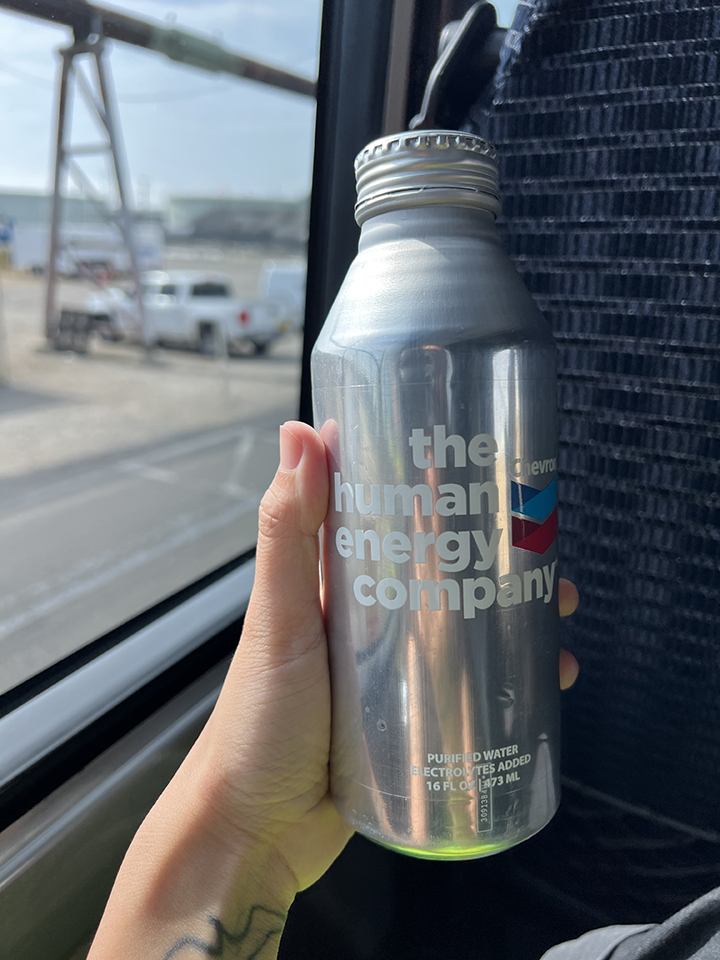

“How do we protect the future from the present?”28 In posing this question, the scholars Zoe Todd, Ozayr Saloojee, and Émélie Desrochers Turgeon argue “to upend and unsettle this anthropogenic and petro-colonial epistemology, to re-call an ontology of relations and relations of relations, truly seeing life in what we’re calling ‘the kerosphere.’”29 Their vantage point—from both present-day so-called Canada and the histories of “mineral displacings and surfacings” helps to bridge understandings across time and space to these dunes receiving these fossil former beings from underneath the rainforest. As Zoe Todd reminds us, oil is kin, and “it is the machinations of human political-ideological entanglements that deem it appropriate to carry this oil through pipelines running along vital waterways, that make this oily progeny a weapon against fish, humans, water and more-than-human worlds.”30 I recall all this while sipping purified water with added electrolytes out of a branded metal reusable bottle labeled “Chevron: The human energy company,” on the hour-long bus tour in November.

I listen as our tour guide, a pleasantly spirited lab director, informs us that his spouse works at the refinery, too, before explaining, “Today is the one day of the year we invite the public in. The other three hundred and sixty-four days of the year, we spend most of our time making sure we are not seen, heard, or smelled.” I hear this sentiment and specific turn of phrase repeated at least two more times that day. After the tour, we are deposited in the employees’ park, where we are encouraged to explore a pop-up exhibit about Chevron’s work in developing renewable energy sources, engage with a Boston Dynamics robot dog, which would purportedly patrol the refinery grounds, and receive a branded wireless charger after participating in all the activities. I am attempting to exercise my “right to look,” as Nicholas Mirzoeff describes—“to shape an autonomous realism that is not only outside authority’s process but antagonistic to it,”31 rejecting the contradictions between their “neighborly” statements and the physical technologies of both policing and branding. At day’s end, however, I am dismayed to be even slightly disarmed by the lull of public relations–approved calm.

Later that evening, I do charge my phone with the wireless charger. Unsettled by the look of metals (copper? cobalt?) embedded in transparent resin (itself a petroleum product), I watch the percentage rise on the device’s OLED display as the electrical charge arrives through repeated transformations within the utility infrastructure of the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power (LADWP). The largest municipal utility in the United States, LADWP not only owns land and water rights to the Owens Valley in eastern California, from where the City of Los Angeles has stolen its water since 1913, but also operates power plants as far as Arizona and Utah.

Recalling the Tlingit scholar Anne Spice, writing on the Wet’suwet’en people’s resistance at Unist’ot’en Camp (in what is currently called British Columbia), brings me back to reality. Even while settler states like the so-called United States, Canada, and Israel codify the use of oil and gas infrastructures in settler colonial invasion under the guise that these infrastructures are “critical” to their national projects, there exist and have existed liberatory, decolonial alternatives: “When Indigenous land defenders point to ‘our critical infrastructures,’ they are pointing to another set of relations that sustains the collective life of Indigenous peoples—the human and non-human networks that have supported Indigenous polities on this continent for tens of thousands of years.”32

From the environmental justice coalition Stand Together Against Neighborhood Drilling Los Angeles (STAND-LA), to the Indigenous-led Ceibo Alliance and Amazon Frontlines, resistance movements exist, thrive, and fight on our collective behalf in Los Angeles, Ecuador, and beyond. Along the literal and figurative pipelines, community members, grassroots organizers, cultural workers, and allies have cultivated abundant lineages of verbal, visual, and spatial strategies in their “right to look” and in the creation of distinct and interrelated futurities. I’m thinking again about Macarena Gómez-Barris writing about a submerged perspective as well—a fish’s-eye episteme: “an underwater perspective that sees into the muck of what has usually been rendered in linear and transparent visualities.”33 A body, peering through a chain-link fence, tripping on the edge of a sandy curb, and sharing what they see in context and in community, becomes, with each second, closer to a collective practice of looking and moving into shared futures together.

-

Anakaren Andrade, Tony Carrera, Francisca Martinez, Lizet Pantoja, Margaret Rubens, and Erick Zerecero, “Urban Oil Drilling and Community Health: Results from a UCLA Health Survey,” UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, 2017. ↩

-

Ryan Menezes and Mark Olalde, “California Has Thousands of Old Oil Wells. How Many Are in Your Neighborhood?” Los Angeles Times, March 4, 2020. ↩

-

Emily Witt, “The End of Oil Drilling in L.A.,” New Yorker, March 3, 2022, link. ↩

-

The Cardiff Tower, an oil derrick in Pico-Robertson, camouflages itself with a facade matching that of nearby temples. The San Vicente Drill Site operates in a windowless void cut from the Beverly Center shopping center in Beverly Hills. ↩

-

Erin Brockovich, “This Lawyer Should Be World-Famous for His Battle with Chevron – but He’s in Jail,” Guardian, February 8, 2022, link. ↩

-

Kate Aronoff, “Don’t Expect Gas Companies to Pause Business on Gaza’s Behalf,” New Republic, November 14, 2023, link. ↩

-

Kyle Ferrar, “Index of Oil and Gas Operator Health in California,” Fractracker Alliance, January 30, 2024, link. ↩

-

Dan Bacher, “Big Gas and Big Oil Spent a Record \$27 Million Lobbying in California in 2023!” Elk Grove News, February 12, 2024, link. ↩

-

Neeraj Bhatia, “The Other California,” Footprint, no. 23 (Autumn/Winter 2018): 115. ↩

-

Chevron Corporation, “Chevron El Segundo Refinery: About the Refinery,” accessed November 1, 2023, link. ↩

-

Historically, Chevron (formerly Standard Oil of California) sought to attract industries that required vast amounts of fuel. It is by design that Chevron’s and Raytheon’s campuses (as well as other military defense and aerospace corporations like Lockheed Martin) are neighbors in El Segundo, as their profits and complicity in US and Western imperialism work hand in hand. See Taylor Miller, “A Pause, On Possibility,” Avery Review, no. 65 (December 2023), link. ↩

-

Founded in 1912, a year after El Segundo, Manhattan Beach, as of 2020, has a population that is 74.4 percent white, with a median income of $187,217 (in 2022 dollars), compared with 65.9 percent and $142,596 in El Segundo and 42.2 percent and $76,244 in the city of Los Angeles (2020 US Census). ↩

-

City of Manhattan Beach, Code of Ordinances, Title 4 - Public Welfare, Morals, and Conduct, Chapter 4.104 - Oil Wells, Refineries, 4.104.060 - Refineries. ↩

-

Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy, “Land History: Gabrieleno-Tongva Villages,” accessed November 1, 2023, link. ↩

-

Dorany Pineda, “Study of US Oil Refineries Ranks Chevron El Segundo as Worst Emitter of Two Water Pollutants,” Los Angeles Times, January 26, 2023. ↩

-

WAI Architecture Think Tank, “Letter to Our Daughter Ema Yuizarix,” The Funambulist, no. 40 (February 14, 2022). ↩

-

For these understandings of the refinery’s historical context, I am indebted to Edgar, Lillian, and Emma for their leap of faith in deep-diving into this research with me in the Fall of 2021. See Lillian Liang, Emma Ramirez, Edgar Reyna, Brenda Zhang, "The El Segundo Refinery: Whiteness, Imperialist Expansion and Extractive Infrastructures," Critical Planning 26 (2023), link. ↩

-

Fred W. Viehe, “Black Gold Suburbs: The Influence of the Extractive Industry on the Suburbanization of Los Angeles, 1890–1930,” Journal of Urban History 8, no. 1 (November 1981): 3. ↩

-

Daniel G. Cumming, “Black Gold, White Power: Mapping Oil, Real Estate, and Racial Segregation in the Los Angeles Basin, 1900–1939,” Engaging Science, Technology, and Society 4 (March 2018): 85–110. ↩

-

Shauna Marie Mulvihill, “A Tale of Two Suburbs, or, The Urban Fortunes of El Segundo and Hawthorne, California, 1905–1960,” Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, 2005. ↩

-

Mulvihill, “A Tale of Two Suburbs.” ↩

-

Angeline Robertson, “Linked Fates: How California’s Oil Imports Affect the Future of the Amazon Rainforest,” Stand.earth and Amazon Watch, 2021, 2. ↩

-

Roberton, “Linked Fates,” 30. ↩

-

Chevron Corporation, “Exploration and Production in the Middle East,” accessed February 9, 2024, link. ↩

-

Edward W. Soja, Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory (New York: Verso, 1989), 191. ↩

-

Macarena Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 2. ↩

-

WAI Think Tank, Nathalie Frankowski, and Cruz Garcia, “Notes on (Post-)Modernist Abstractions and (Post-)Colonial Resolutions,” Jencks Foundation, 2023, link. ↩

-

Zoe Todd, Ozayr Saloojee, and Émélie Desrochers Turgeon, “Kerosphere,” in An Anthropogenic Table of Elements, ed. Timothy Neale, Courtney Addison, and Thao Phan (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2022), 96. ↩

-

Todd et al., “Kerosphere,” 98. ↩

-

Zoe Todd, “Fish, Kin and Hope: Tending to Water Violations in amiskwaciwâskahikan and Treaty Six Territory,” Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry 43, no. 1 (Spring 2017): 107. ↩

-

Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Right to Look (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 25. ↩

-

Anne Spice, “Fighting Invasive Infrastructures: Indigenous Relations Against Pipelines,” in Paths to Prison: On the Architectures of Carcerality, ed. Isabelle Kirkham-Lewitt (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2020), 357. ↩

-

Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone, 103. ↩

Bz Zhang is an architect, organizer, and artist based in Tovaangar. They are a core organizer with the Design As Protest Collective and Dark Matter U and a project manager with the Los Angeles Neighborhood Land Trust, where they work with communities toward environmental justice through design, construction, and stewardship of public green spaces. Their design and research practice wonders aloud about representations of violence and the violence of representations by asking questions both using and about disciplinary tools of art and architecture. Bz is a 2022 Journal of Architectural Education Fellow, 2021 USC Citizen Architect Fellow, and a licensed architect in California. Previously, they have taught architecture at the University of Southern California, California College of the Arts, University of Michigan, and University of California, Berkeley. In their free time, they look for birds and trash in the Los Angeles River.