Corner an architect in the grips of a particularly fascinating design problem and ask them what they’re doing. It’s likely their answer will sound like a foreign language—a stream of jargony terms and obscure references. What trade journals have they been flipping through? What depths of the internet have they been scouring? Who are they following? Untangling convoluted “webs of significance” is a familiar exercise for ethnographers, but the trends of architecture are rarely seen as serious reflections of coherent cultural groups.1 What does it mean for an approach to architecture—or a technique, or a style—to belong to a particular community, a culture?

The notion that architecture is a product of its culturally specific context is not new. One version of this idea was presented at the 1964 MoMA exhibition “Architecture without Architects.” Rather than offering a clear set of answers, its curator, Bernard Rudofsky, composed the show to provoke and beguile. Inside the exhibition, New Yorkers spied one another as predator and prey, locking eyes through a screen of undergrowth, which was represented by an idiosyncratic display system of perforated walls of large-scale photographs depicting a jumble of vernacular built environments from around the world. Rudofsky’s exhibition text revels in the disjunction of modern city dwellers—members of a society that considered itself “advanced”—finding themselves awestruck by traditional built forms they hardly understood. “In civilizations less ponderous than ours,” one caption read, “enclosures made from woven matting are considered fit for kings.” A tamer title for the show might have been “Learning from Vernacular Building Traditions.” Like Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi’s 1972 study, Rudofsky positioned ethnographic fieldwork as a basis for architectural expertise. Go to Las Vegas, the suburbs, an isolated village, or the remotest desert, learn the local architectural patois, and report back. Much of the research in contemporary architecture—the foundation of its claim to status as a discipline—continues to rely on this formula.2

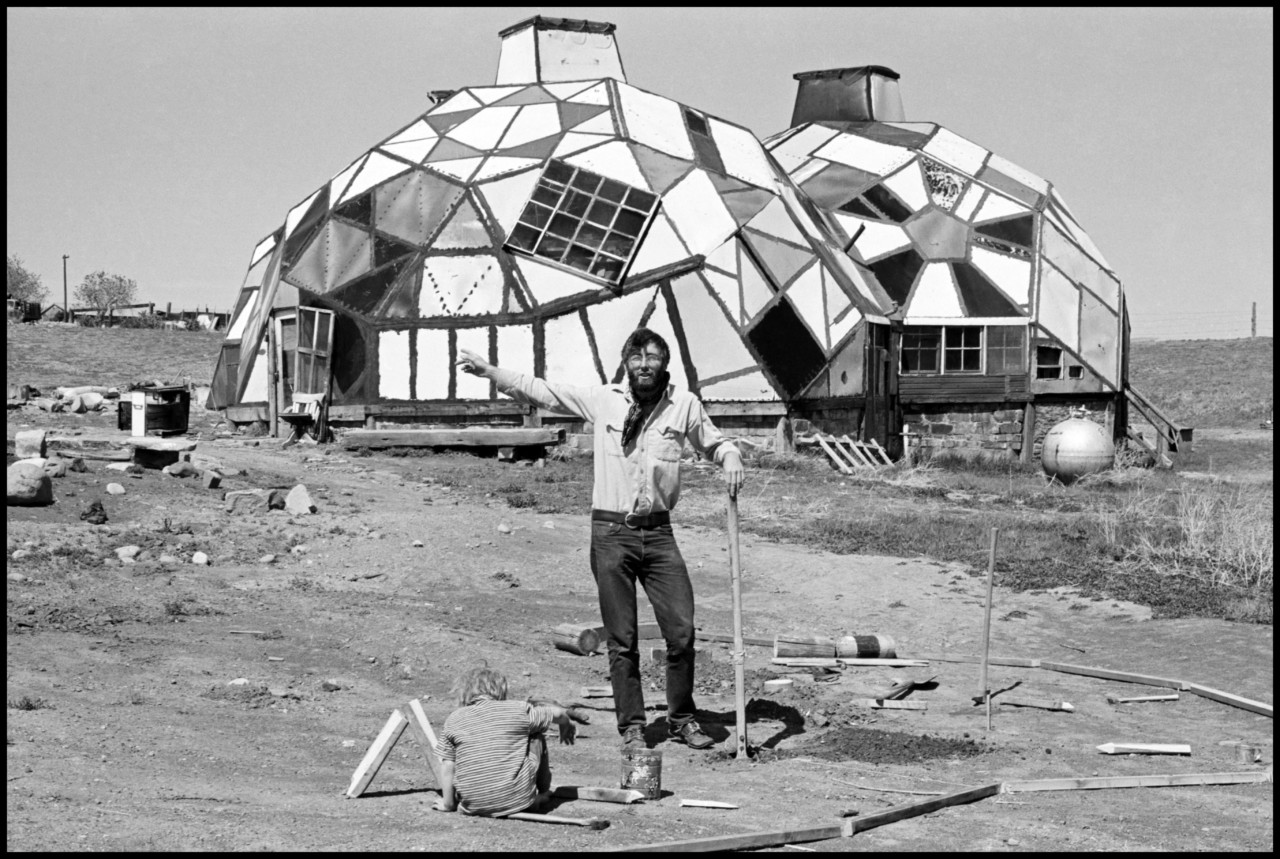

Now imagine an alternate title for Andrew Witt’s recent book Formulations: Architecture, Mathematics, Culture (2022). What if it had been called Geometry without Geometers, a survey of the world of everyday geometry employed by architects? It’s a slightly comical premise, resulting perhaps in charmingly bizarre constructions like the scrap-metal domes of hippie-built Drop City. But as Witt illustrates in nine dense chapters, the vernacular mathematics used by architects over the last century produced not only sound and functional buildings but marvels of form the likes of which mathematicians could only dream of. The book is easily the most comprehensive and engaging account of what he calls the “mathematical turn” in twentieth-century architecture, a precursor to the computerized architectural culture of today.

Witt’s book is the latest episode in a methodological shift that occurred largely over the hundred-year period between Gottfried Semper’s Four Elements of Architecture (1851) and Rudofsky’s “Architecture without Architects.” Following in the anthropological tradition means taking seriously the idea that we’ve become “digital natives.”3 And so the first step is to do some fieldwork. Go to “the digital,” observe the ways of its inhabitants, and report back.

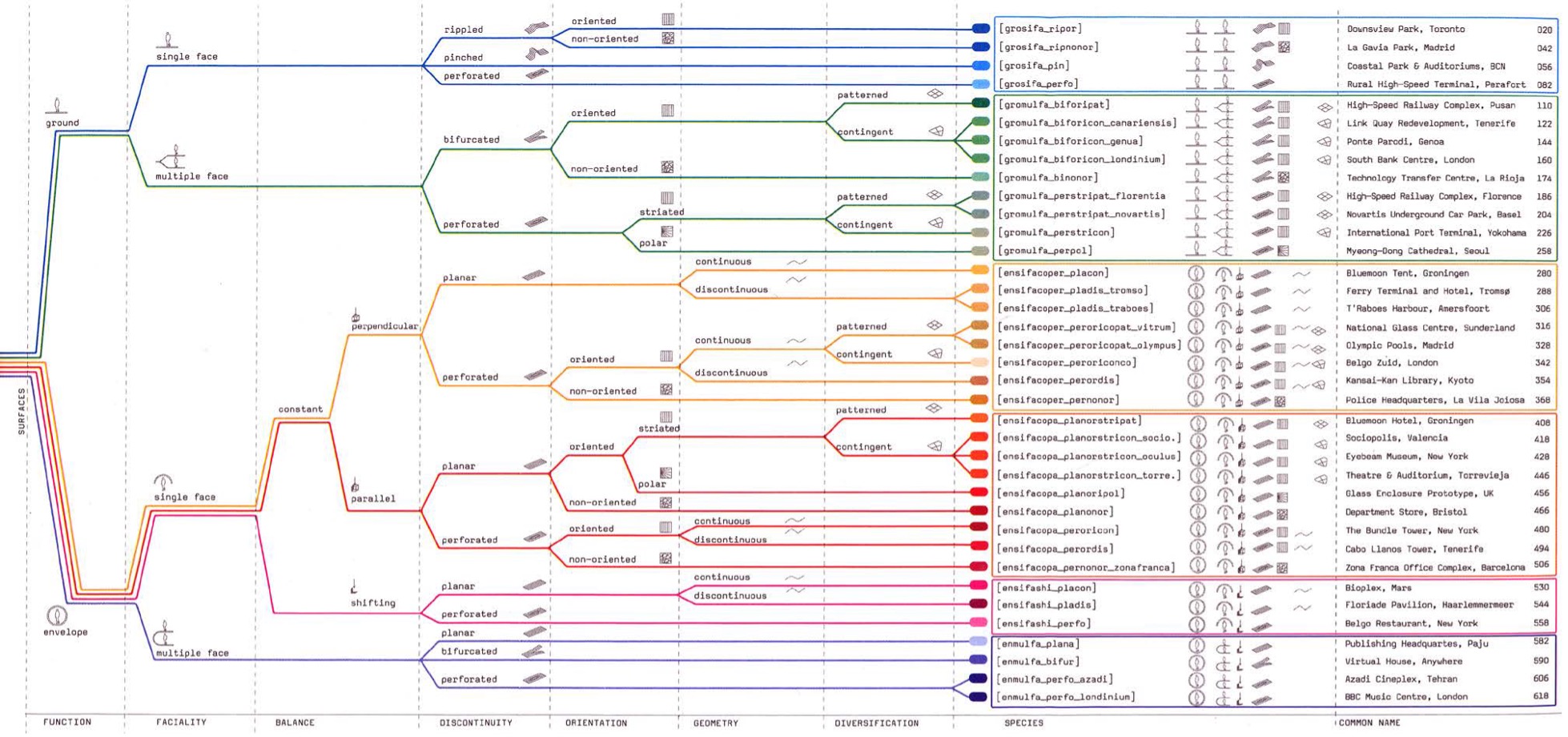

The flora and fauna of the digital world are what Witt calls “mathematical species”—crystals, matrices, knots, lattices, epicycloids, hyperboloids—that branch into exotic subspecies and spawn various built forms. The metaphor of evolutionary diversity has long been a favorite of mathematician-philosophers, and it became a compelling way of organizing a field of knowledge by a generation of architects at the end of the last millennium.4 Greg Lynn’s era-defining Animate Form (1999) arrived in the midst of a two-decade-long exploration of mathematics-based formal strategies, while FOA’s Phylogenesis (2003) mapped the family of forms with the verve of a nineteenth-century naturalist.

Witt was previously the director of research at Gehry Technologies, the company that nurtured some of the key tools and techniques of digital architecture to maturity, before starting his own computationally advanced firm, Certain Measures, with cofounder Tobias Nolte. In other words, he encountered many of his book’s “mathematical species” out in the field, as a designer, before tracing their genealogies. His prime criterion for inclusion appears to have been the fecundity of creative pathways a mathematical approach opens for contemporary architects: “Today, computational tools that encapsulate mathematical methods are radically short-circuiting the path to expertise... and democratizing access to the systems and aesthetics of mathematical design. Old hierarchies of training and knowledge are eroding, and in their place a new kind of technical culture of opportunistic hacking, open code sharing, and recombinant invention flourishes.”5

Witt’s method is indebted to anthropologists like André Leroi-Gourhan, who theorized how specific human cultures transform abstract technical tendencies into their own unique worlds of technical objects—what he calls the “artificial envelope” or “curtain of objects” with which cultures surround themselves.6 Each chapter of Formulations focuses on an encounter between a mathematical species and the mathematicians, inventors, and designers who wrangled them from the realm of pure math into the built world by means of myriad devices and models. We learn in chapter 9, for instance, how hyperbolic surfaces similar to the roof of Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp chapel were made a subject of architectural knowledge in an earlier era, when Christopher Wren developed a means of grinding lenses using hyperboloids of revolution around 1669. Wren’s grinders brought the math out of the realm of mental visualization and into the world of tangible, useful objects—putting the possibility of larger hyperbolic constructions tantalizingly close at hand. Formulations offers dozens of brilliant drawings of this kind of mathematical object, each of which opens an avenue of creative exploration. “Each new formal system became a matter of technique which, with appropriate training, anyone could master,” says Witt.7 In this sense, another overall theme of the book is the democratization of expert knowledge. Witt shows how, once expertise is embodied in objects, it tends to become common property.8 Just as Wren’s grinders opened the field of optometry—grinding a lens became a little easier—the virtual modeling tools in software like Rhinoceros 3D open the field of form-making. In the past, if you wanted a strangely shaped piece of plastic, you had to call up a sculptor or an engineer. Now, in some cities you can go to the municipal library, use their modeling software, and output your creation on a public-access 3D printer. The relevant techniques are baked into the software and presented to the user as a matter of relatively straightforward virtual manipulation.

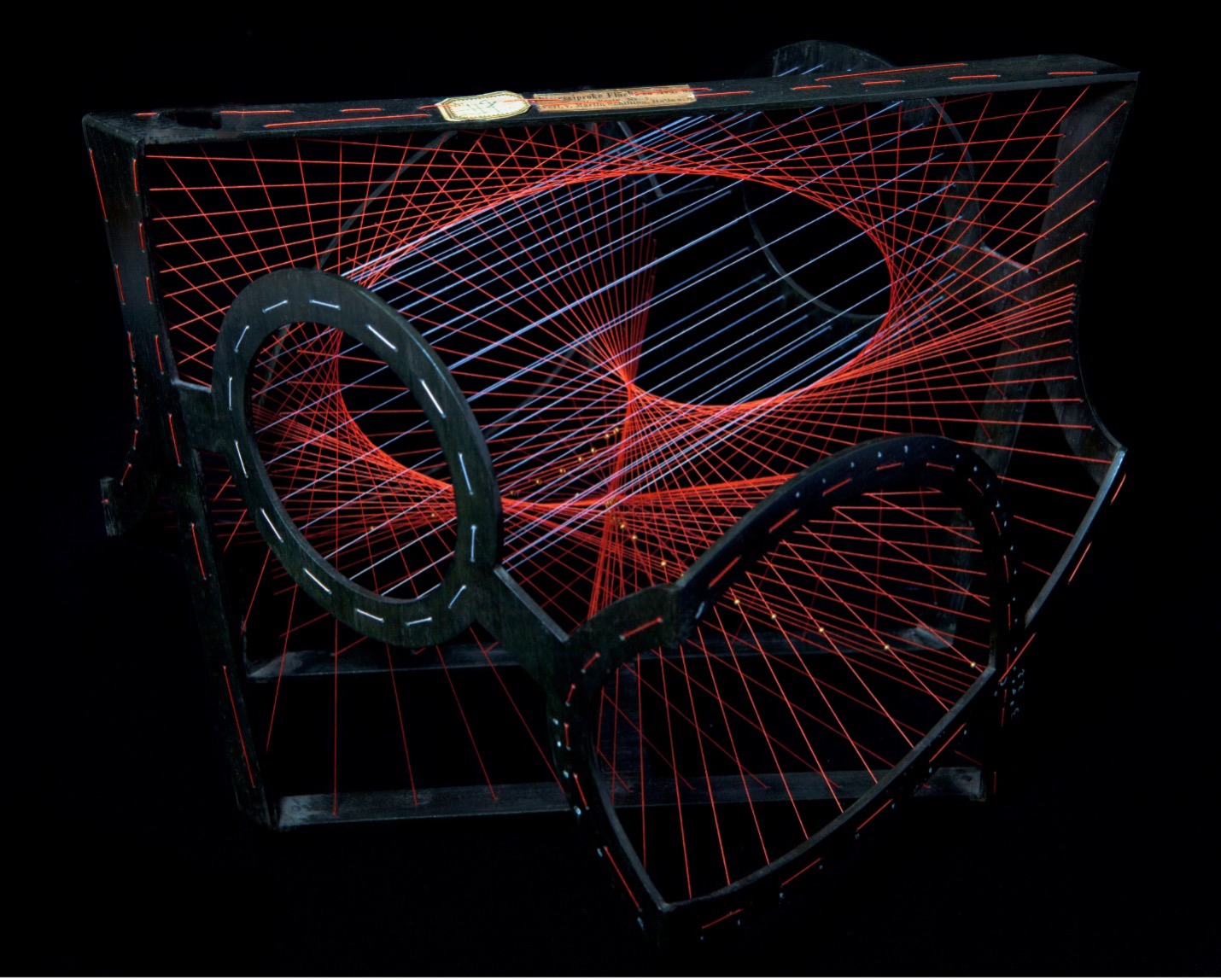

Around each assemblage of knowledge, devices, and forms, Witt charts the formation (and, in most cases, the subsequent dissolution) of communities with their own distinctive languages. He frames his study with the concept of a “thought collective,” a term borrowed from the sociologist of science Ludwik Fleck that Witt describes as “a critical cluster of mutually reinforcing researchers elaborating a common technical culture.”9 Judging by Witt’s examples, each thought collective experienced an effervescence of formal invention lasting a few decades: bursts of creativity that reach their conclusion as paths of exploration are exhausted and their most fruitful discoveries are incorporated into mainstream practice. String models of ruled surfaces, for example, were developed by geometers in the nineteenth century and taken up by avant-garde artists and architects, including Naum Gabo and Le Corbusier, between the 1930s and the 1960s. Physical modeling techniques like these lent a competitive edge in the game of formal invention. While more recent “post-digital” architects tend to abstain from technological one-upmanship, the contemporary notion of a self-organizing disciplinary commons treads on terrain familiar to the quasi-anarchist / quasi-neoliberal hacker culture of the 1990s—which itself developed from the nascent open source software community of the 1960s.10 The amorphous British architecture cooperative Assemble, for instance, employs an ethos of grassroots sharing that flourished decades earlier within the thought collectives Witt documents.

Let’s Talk Techniques

What’s at stake in Witt’s book is the place of technical knowledge in architecture. Formulations offers an important corrective to the inclination—now dominant among many historians and theorists—to see science and technology as instilling dangerous habits of thought. To understand this position, we need to step back and view the book within a longer tradition of critical scholarship on science and technology. Following the mechanized horrors of the First and Second World Wars, many critics and scholars developed a suspicion of technics and technology. Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno connected the dots between the Enlightenment fixation on rationality and projects of eugenics, while Michel Foucault showed how barbarities carried out in the name of medicine were not aberrations but were inextricable from contemporaneous scientific discourse.11 A variation on this analytical method was offered by Bruno Latour, whose actor-network theory cast people as nodes in techno-social systems. Latour’s “flat ontology” sees objects as having agency comparable to people.12 If introducing a gun into a situation changes the possibilities of action (usually for the worse), could not the same be said for a spreadsheet (which reduces people to tables of numbers)? The implication of all this theorizing was neatly summed up by Foucault: “People have dreamed of liberating machines. But there are no machines of freedom, by definition.”13

A popular tendency in more recent critical scholarship has been to expose the deep flaws and negative side effects of technology. In Log’s “New Ancients” issue, for instance, which heralded a post-digital movement in architecture, Zeynep Çelik Alexander drew a line in the sand between the humanities and the sciences, urging architects to choose the former.14 She described “a fundamental epistemological and ethical change in the academic landscape,” and cautioned that “when data eclipses all other forms of evidence in the discipline, the world is rendered as an unbroken, uninterrupted field devoid of politics.” Despite the nuances of her argument, the takeaway was clear: good theory should avoid “data in its various guises.” A hermeneutics of suspicion is the safest bet for an aspiring theorist—or architect, for that matter.

Architectural theorists have tended to take the high road of enlightened skepticism, casting the theorist/observer as someone who knows better than the locals (the architect-technicians). This was recognized long ago as a deep-seated flaw in anthropological methodology; one of the most famous public intellectuals of the twentieth century, Claude Lévi-Strauss, made his career attempting to undo it. Many early twentieth-century anthropologists believed that certain human groups (the San people of southern Africa were a popular case to study at the time) were stuck in “older” social configurations and didn’t know how to move beyond them—that is, they had failed to “evolve” from clan-based societies to more “advanced” neolithic civilizations. Lévi-Strauss argued instead that people have the same capacities everywhere and make rational decisions about the forms their societies take. It was a big shift, although it played out in subtle ways: above all, in the ways anthropologists structured their arguments. Anthropologists following this line of thought found better ways of dividing up knowledge and describing cultures other than their own.15

A key development in the history of anthropology and its methods was the principle of symmetry. In some ways, it’s a simple idea: try not to apply concepts from your own culture when attempting to understand another.16 Each culture is a self-contained, coherent system, and understanding a culture’s system of evaluation will only be more difficult if external moral codes are added into the mix. For that matter, it’s also a good idea to assume upfront that any culture will have, at a basic level, a means of making moral judgments—their own notions about what's right or wrong, good or bad.

Returning now to contemporary technical cultures, the claim that a technology-using architect who turns to “the evidentiary regime of the natural sciences” is giving up their means of producing “justifications” based on “values” (a category often implied to be within the domain of the humanities) divides up knowledge in a particular way: the architectural theorist is seen as having access to a way of understanding that the people they write about are seen as lacking. It’s not that this framing is wrong—the so-called two cultures debate embroiled scientists and humanists inconclusively for decades. Rather, it’s an analytical choice that has the drawback of being asymmetrical.

What if we took a different approach and insisted that scientists always do in fact deal with values? This was a central theme of the recent movie Oppenheimer: might the Manhattan Project have gone differently, and the atrocities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki been avoided, if science were seen as always and fundamentally embroiled with ethics? The contemporary philosophy of science, for its part, was founded in part on the idea that there’s no such thing as a value-neutral theory or concept.17 The notion that we live within two cultures in opposition—science versus humanities—is a distinctly problematic framing from the point of view of contemporary anthropology. Knowledge need not be divided up in this way. Maybe fields of knowledge overlap, or maybe architects have a unique potential to combine the best insights of multiple worlds by becoming a scientist in the morning and a theorist in the afternoon. The principle of symmetry suggests that we should begin with the assumption that all cultures have ways of dealing with things like politics and values, even if they’re formulated in unfamiliar ways.

Witt avoids the pitfall of asymmetry by positing a different place for technical knowledge: “Through the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, mathematics persisted as a kind of ur-science which oscillated between the poles of naturalism and antinaturalism.”18 In this view, technical knowledge is not an endpoint but a trading zone: “Mathematics was a conceptual intermediary for the rapprochement of natural sciences with creative method.”19 Mathematics emerges from Witt’s account as a common language that animated an ebb and flow of subcultures in architecture, and which sometimes reached mainstream popularity.

Here it’s worth pointing out that Witt is not an ethnographic theorist, and he does not detail how cultures and languages work, nor the conceptual nuances of cultural groupings. Rather than explain, he shows through dozens of examples that mathematics exists not in some pristine abstract realm but rather jostling among everyday spoken languages and the specialized languages of technical subcultures.

Witt writes as a historian and his narrative is centered neatly in the past, but Formulations has a clear relevance for the present. If some approaches to architecture have been incubated within technical subcultures, and if technical subcultures operate by means of specialized languages, we might ask: What are the languages we should learn today so we can go about designing the types of architecture we want? Geoengineering, to take one loaded example, that attempts to alter earth systems to “undo” the effects of climate change, has been raised as a matter of concern by offices like Design Earth. Due to the intersecting crises of the present, architects have been drawn into considerations of increasingly large and complicated issues. Why be content designing a single house when the real problem has to do with the whole housing system? Why not try to design the system itself?

While motivation to engage in design at such a scale and complexity may come from the clarity that critical theory has to offer, Witt’s analysis of technical subcultures suggests that techniques are best learned differently—in the way languages are learned. Democratically minded architects might want to eschew all the technical verbiage and engagement with the technical histories that Formulation details, but he suggests that’s the wrong way to go. We should learn and seize the coded language and jargon, or they will remain in the hands of a technocratic elite. If you want to design a complicated system, it makes sense to go to the culture that makes systems its home—engineers, coders, geeks—and learn their ways. Bring Formulations along—it will make an excellent field guide.

-

For a classic cultural anthropology inspired by structural linguistics, see Clifford Geertz, “Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight,” in The Interpretation of Cultures (New York: Basic Books, 1973). ↩

-

Brendan Moran, “Research: Toward a ‘Scientific’ Architecture,” in Architecture School: Three Centuries of Educating Architects in North America, ed. Joan Ockman (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 286–391. ↩

-

The consequences of digital culture becoming second nature were memorably outlined by Stan Allen in 2005: See Stan Allen, “The Digital Complex,” Log 5 (2005): 93–99. ↩

-

See, for example, L. E. J. Brouwer, “Consciousness, Philosophy and Mathematics,” in DATA: Directions in Art, Theory and Aesthetics, ed. Anthony Hill (London: Faber & Faber, 1968), 12–21. ↩

-

Andrew Witt, Formulations: Architecture, Culture, Mathematics (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022), 388. ↩

-

André Leroi-Gourhan, Milieu et techniques (Paris: Albin Michel, 1945). ↩

-

Witt, Formulations, 335. ↩

-

Beyond illustrating this dynamic, many of Witt’s case studies culminate in intriguing historical theses. For example: “The high point for hyperbolic architecture corresponded with a golden age of published trade magazines” (329). This book contains the seeds of many possible dissertations. ↩

-

Witt, Formulations, 26. The philosopher Randall Collins similarly makes the case that all discoveries happen in groups. See Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000). ↩

-

Mario Carpo, in his latest book, notes the neoliberal orientation of 1990s digital architecture. See Mario Carpo, Beyond Digital: Design and Automation at the End of Modernity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2023), 157. ↩

-

Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment (New York: Herder and Herder, 1972); Michel Foucault, Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason (New York: Random House, 1965). ↩

-

Levi Bryant, “The Four Theses of Flat Ontology,” in The Democracy of Objects (Ann Arbor, MI: Open Humanities Press, 2011). ↩

-

Michel Foucault, “Space, Knowledge, and Power,” Skyline (March 1982). ↩

-

Zeynep Çelik Alexander, “Neo-Naturalism,” Log 31 (Spring/Summer 2014): 23–30. ↩

-

David Graeber and David Wengrow develop this theme extensively in their recent bestseller The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (New York: Macmillan, 2012). ↩

-

Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993), 103. Rottenburg summarizes symmetry thus: “A symmetrical methodology applies the same language to (1) right and wrong statements (truth and errors; knowledge and belief), (2) human beings and material objects (in order to overcome the nature-society divide), (3) western and non-western societies, and (4) anthropological and non-anthropological practice.” See Richard Rottenburg, “Towards an Ethnography of Translocal Processes and Central Institutions of Modern Societies,” in The Task of Ethnology: Cultural Anthropology in Unifying Europe, ed. Aleksander Posern-Zielinski (Poznań: Drawa, 1998), 59–66. ↩

-

See, e.g., Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962). ↩

-

Witt, Formulations, 14. ↩

-

Witt, Formulations, 14. ↩

Matthew Allen is a visiting assistant professor at Washington University who studies the history and theory of architecture, computation, and aesthetic subcultures. He holds a PhD and a Master of Architecture degree from Harvard University, and is the author of Flowcharting: From Abstractionism to Algorithmics in Art and Architecture.